economics

…an agreement to feature Google’s search engine as the preselected choice on Apple’s iPhone and other devices. […] Apple had arranged the deal to require periodic renegotiations, according to a former senior executive, and each time, it extracted more money from Google. […]

Steve Jobs, Apple’s co-founder, once promised “thermonuclear war” on his Silicon Valley neighbor when he learned it was working on a rival to the iPhone. […] “I’m going to destroy Android,” Mr. Jobs told his biographer. […] A year later, Apple introduced Siri. Instead of Google underpinning the virtual assistant, it was Microsoft’s Bing. […] Around 2017, the deal was up for renewal. Google was facing a squeeze, with clicks on its mobile ads not growing fast enough. Apple was not satisfied with Bing’s performance for Siri. And Mr. Cook had just announced that Apple aimed to double its services revenue to $50 billion by 2020, an ambitious goal that would be possible only with Google’s payments. […] By the fall of 2017, Apple announced that Google was now helping Siri answer questions, and Google disclosed that its payments for search traffic had jumped. […]

Nearly half of Google’s search traffic now comes from Apple devices, according to the Justice Department, and the prospect of losing the Apple deal has been described as a “code red” scenario inside the company. When iPhone users search on Google, they see the search ads that drive Google’s business. They can also find their way to other Google products, like YouTube.

A former Google executive, who asked not to be identified because he was not permitted to talk about the deal, said the prospect of losing Apple’s traffic was “terrifying” to the company. […]

Apple now receives an estimated $8 billion to $12 billion in annual payments — up from $1 billion a year in 2014 — in exchange for building Google’s search engine into its products. It is probably the single biggest payment that Google makes to anyone and accounts for 14 to 21 percent of Apple’s annual profits. That’s not money Apple would be eager to walk away from.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

economics, google, law | October 25th, 2020 8:19 am

[U]ntil recently, there’s one group of potential Biden voters who have not been the subject of voter outreach: kinky, submissive male Trump supporters with humiliation fetishes.

Now, thanks to a Las Vegas-based professional dominatrix named Empress Delfina, this once-overlooked voting bloc is covered—and may be voting Biden. By force.

Her ad for this service reaches out to these potential Biden voters as follows: “Here’s your chance to get berated for being the degenerate Trump supporter you are. I reverse the brainwash you’ve succumbed to that made you into a Simple Stupid Drone. By using lethal mind fucking language and making you repeat dumbass chants like your Bullshitter in Chief made you do to warp you into submission, I transfer your ownership to me for my personal gain and entertainment. Embrace that you need to be saved from being a Trump-bot. Call now to begin your Trump Conversion Therapy.”

At $1.99 a minute, business is booming. […]

“Half the guys just want to argue. They’re not open to getting converted at all. They just call to start berating my liberal politics. And I’m like, ‘Hey, if you want to pay me $1.99 a minute to argue with me, go right ahead.’ […] But the other half is actually open to being persuaded.”

{ Daily Beast | Continue reading }

U.S., economics, fetish | October 24th, 2020 4:39 pm

People who manage investment funds have greatly increased in number and pay. Once their management fees are taken into account, they tend to give lower returns than simple index funds. Investors seem willing to accept such lower expected returns in trade for a chance to brag about their association should returns happen to be high. They enjoy associating with prestigious fund managers, and tend to insist that such managers take their phone calls, which credibly shows a closer than arms-length relation.

{ OvercomingBias | Continue reading }

sheep and formaldehyde solution { Damien Hirst, The Tranquility of Solitude (for George Dyer), Damien Hirst, The Tranquility of Solitude (for George Dyer), 2006 }

economics | October 7th, 2020 4:37 pm

Data analytics company Palantir Technologies and workplace software maker Asana Inc are set to debut on the U.S. stock market on Wednesday bypassing an initial public offering (IPO). […]

[S]ome investors and corporate executives have been pushing to shed investment banks as their middlemen. For years, they have criticized IPOs as chummy deals that allowed bankers to allocate the most shares to their top clients. […] “If Palantir and Asana are successful, which they should be, more and more companies will return to looking seriously at direct listings,” Narasin added. […]

In 2020, the price of a newly listed company’s shares has risen by an average of 38% on the first day of trading, according to IPOScoop data and Reuters calculations.

This has fueled renewed criticism among investors snubbed by the investment banks underwriting the IPOs, as well as suspicion among some companies that bankers are leaving money on the table in their IPO to help create a first-day trading “pop”. […]

In a direct listing, no shares are sold in advance, as is the case with IPOs. The company’s share price in its market debut is determined by orders coming into the stock exchange.

The downside is that the companies involved cannot raise money, though both NYSE and Nasdaq have requested U.S. regulators allow them to change their rules to allow companies to sell new stock in a direct listing.

{ Reuters | Continue reading }

traders | September 29th, 2020 8:24 am

In the year 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that, by century’s end, technology would have advanced sufficiently that countries like Great Britain or the United States would have achieved a 15-hour work week. There’s every reason to believe he was right. In technological terms, we are quite capable of this. And yet it didn’t happen. Instead, technology has been marshaled, if anything, to figure out ways to make us all work more. In order to achieve this, jobs have had to be created that are, effectively, pointless. […]

productive jobs have, just as predicted, been largely automated away […] But rather than allowing a massive reduction of working hours to free the world’s population to pursue their own projects, pleasures, visions, and ideas […] It’s as if someone were out there making up pointless jobs just for the sake of keeping us all working. And here, precisely, lies the mystery. In capitalism, this is precisely what is not supposed to happen. Sure, in the old inefficient socialist states like the Soviet Union, where employment was considered both a right and a sacred duty, the system made up as many jobs as they had to (this is why in Soviet department stores it took three clerks to sell a piece of meat). But, of course, this is the sort of very problem market competition is supposed to fix. According to economic theory, at least, the last thing a profit-seeking firm is going to do is shell out money to workers they don’t really need to employ. Still, somehow, it happens.

{ David Graeber | Continue reading }

what I am calling “bullshit jobs” are jobs that are primarily or entirely made up of tasks that the person doing that job considers to be pointless, unnecessary, or even pernicious. Jobs that, were they to disappear, would make no difference whatsoever. Above all, these are jobs that the holders themselves feel should not exist.

Contemporary capitalism seems riddled with such jobs.

{ The Anarchist Library | Continue reading }

image { Alliander, ElaadNL, and The incredible Machine, Transparent Charging Station, 2017 }

economics, ideas | September 3rd, 2020 11:51 am

Moringa oleifera, an edible tree found worldwide in the dry tropics, is increasingly being used for nutritional supplementation. Its nutrient-dense leaves are high in protein quality, leading to its widespread use by doctors, healers, nutritionists and community leaders, to treat under-nutrition and a variety of illnesses. Despite the fact that no rigorous clinical trial has tested its efficacy for treating under-nutrition, the adoption of M. oleifera continues to increase. The “Diffusion of innovations theory” describes well the evidence for growth and adoption of dietary M. oleifera leaves, and it highlights the need for a scientific consensus on the nutritional benefits. […]

The regions most burdened by under-nutrition, (in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean) all share the ability to grow and utilize an edible plant, Moringa oleifera, commonly referred to as “The Miracle Tree.” For hundreds of years, traditional healers have prescribed different parts of M. oleifera for treatment of skin diseases, respiratory illnesses, ear and dental infections, hypertension, diabetes, cancer treatment, water purification, and have promoted its use as a nutrient dense food source. The leaves of M. oleifera have been reported to be a valuable source of both macro- and micronutrients and is now found growing within tropical and subtropical regions worldwide, congruent with the geographies where its nutritional benefits are most needed.

Anecdotal evidence of benefits from M. oleifera has fueled a recent increase in adoption of and attention to its many healing benefits, specifically the high nutrient composition of the plants leaves and seeds. Trees for Life, an NGO based in the United States has promoted the nutritional benefits of Moringa around the world, and their nutritional comparison has been widely copied and is now taken on faith by many: “Gram for gram fresh leaves of M. oleifera have 4 times the vitamin A of carrots, 7 times the vitamin C of oranges, 4 times the calcium of milk, 3 times the potassium of bananas, ¾ the iron of spinach, and 2 times the protein of yogurt” (Trees for Life, 2005).

Feeding animals M. oleifera leaves results in both weight gain and improved nutritional status. However, scientifically robust trials testing its efficacy for undernourished human beings have not yet been reported. If the wealth of anecdotal evidence (not cited herein) can be supported by robust clinical evidence, countries with a high prevalence of under-nutrition might have at their fingertips, a sustainable solution to some of their nutritional challenges. […]

The “Diffusion of Innovations” theory explains the recent increase in M. oleifera adoption by various international organizations and certain constituencies within undernourished populations, in the same manner as it has been so useful in explaining the adoption of many of the innovative agricultural practices in the 1940-1960s. […] A sigmoidal curve (Figure 1), illustrates the adoption process starting with innovators (traditional healers in the case of M. oleifera), who communicate and influence early adopters, (international organizations), who then broadcast over time new information on M. oleifera adoption, in the wake of which adoption rate steadily increases.

{ Ecology of Food and Nutrition | Continue reading }

Dendrology, economics, food, drinks, restaurants, theory | September 1st, 2020 4:54 pm

Gendville met Brooks-Church in an Area Yoga class, according to a person who has known the couple for more than a decade. He was “this sexy Spanish guy,” a flâneur type. He had grown up mostly on the resort island of Ibiza, the son of outlaw parents, hippies hunted by the Feds for two antiwar bombings in the ’80s until his mother turned herself in and his father reportedly got caught in Arkansas trying to pick up $6 million in cocaine. Brooks-Church became an adherent of Human Design, a pseudoscience combining astrology and chakras, which was created on Ibiza in 1992 by an advertising executive named Alan Krakower, who claimed to have received messages on the meaning of life from an entity called “the Voice.” […]

Brooks-Church, 49, was a “green builder” with a construction company called Eco Brooklyn who had spoken about sustainability at the Brooklyn Public Library; he was a vocal advocate for designating the Gowanus Canal a Superfund site, making it eligible for environmental protections. He did CrossFit. Gendville, 45, was the owner of a restaurant called Planted Community Cafe and a local chain of yoga studios, spas, and children’s stores called Area — a “mini-mogul,” according to the New York Times. The pair were currently renting out a brownstone they owned on Airbnb not five miles away, with a tree house and turtle pond, for nearly $800 a night. What could drive two yogic, environmentally conscious, vegan brownstoners to kick out their unemployed tenants during a global pandemic? […]

Though they own two businesses and six properties in one of the country’s most expensive real-estate markets, the landlords were apparently homeless.

{ NY mag | Continue reading }

housing, new york | September 1st, 2020 4:54 pm

Blockchain technology is going to change everything: the shipping industry, the financial system, government … in fact, what won’t it change? But enthusiasm for it mainly stems from a lack of knowledge and understanding. The blockchain is a solution in search of a problem. […]

Once something is in the blockchain, it cannot be removed. For instance, hundreds of links to child pornography and revenge porn were placed in the bitcoin blockchain by malicious users. It’s impossible to remove those.

Also, in a blockchain you aren’t anonymous, but “pseudonymous”: your identity is linked to a number, and if someone can link your name to that number, you’re screwed. Everything you got up to on that blockchain is visible to everyone.

The presumed hackers of Hillary Clinton’s email were caught, for instance, because their identity could be linked to bitcoin transactions. A number of researchers from Qatar University were able to ascertain the identities of tens of thousands of bitcoin users fairly easily through social networking sites. Other researchers showed how you can de-anonymise many more people through trackers on shopping websites.

The fact that no one is in charge and nothing can be modified also means that mistakes cannot be corrected. A bank can reverse a payment request. This is impossible for bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. So anything that has been stolen will stay stolen. There is a continuous stream of hackers targeting bitcoin exchanges and users, and fraudsters launching investment vehicles that are in fact pyramid schemes. According to estimates, nearly 15% of all bitcoin has been stolen at some point. And it isn’t even 10 years old yet.

And then there’s the environmental problem. The environmental problem? Aren’t we talking about digital coins? Yes, which makes it even stranger. Solving all those complex puzzles requires a huge amount of energy. So much energy that the two biggest blockchains in the world – bitcoin and Ethereum – are now using up the same amount of electricity as the whole of Austria.

Carrying out a payment with Visa requires about 0.002 kilowatt-hours; the same payment with bitcoin uses up 906 kilowatt-hours, more than half a million times as much, and enough to power a two-person household for about three months. […]

And for what? This is actually the most important question: what problem does blockchain actually solve? OK, so with bitcoin, banks can’t just remove money from your account at their own discretion. But does this really happen? I have never heard of a bank simply taking money from someone’s account. If a bank did something like that, they would be hauled into court in no time and lose their license. Technically it’s possible; legally, it’s a death sentence.

{ The Correspondent | Continue reading }

acrylic, fluorescent acrylic and Roll-a-Tex on canvas { Peter Halley, Iss, 2019 }

cryptocurrency | August 23rd, 2020 1:37 pm

Some luxury brands have started adding surveillance to their arsenal, turning to blockchains to undermine the emergence of secondary markets in a way that pays lip service to sustainability and labor ethics concerns. LVMH launched Aura in 2019, a blockchain-enabled platform for authenticating products from the Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Marc Jacobs, and Fenty brands, among others. Meanwhile, fashion label Stella McCartney began a transparency and data-monitoring partnership with Google for tracking garment provenance, discouraging fakes and promising to ensure the ethical integrity of supply chains. Elsewhere, a host of fashion blockchain startups, including Loomia, Vechain, and Faizod, have emerged, offering tracking technologies to assuage customer concerns over poor labor conditions and manufacturing-related pollution by providing transparency on precisely where products are made and by which subcontractors. […]

Companies such as Arianee, Dentsu and Evrythng also aim to track clothes on consumers’ bodies and in their closets. At the forefront of this trend is Eon, which with backing from Microsoft and buy-in from mainstream fashion brands such as H&M and Target, has begun rolling out the embedding of small, unobtrusive RFID tags — currently used for everything from tracking inventory to runners on a marathon course — in garments designed to transmit data without human intervention. […]

According to the future depicted by Eon and its partners, garments would become datafied brand assets administering access to surveillance-enabled services, benefits, and experiences. The people who put on these clothes would become “users” rather than wearers. In some respects, this would simply extend some of the functionality of niche wearables to garments in general. Think: swimsuits able to detect UV light and prevent overexposure to the sun, yoga pants that prompt the wearer to hold the right pose, socks that monitor for disease risks, and fitness trackers embedded into sports shirts. […]

According to one potential scenario outlined by Eon partners, a running shoe could send a stream of usage data to the manufacturer so that it could notify the consumer when the shoe “nears the end of its life.” In another, sensors would determine when a garment needs repairing and trigger an online auction among competing menders. Finally, according to another, sensors syncing with smart mirrors would offer style advice and personalized advertising.

{ Real Life | Continue reading }

related { Much of the fashion industry has buckled under the weight of the coronavirus — it appears to have sped up the inevitable }

cryptocurrency, fashion, spy & security, technology | August 23rd, 2020 9:47 am

according to its own IPO filings, Uber can only be profitable if it invents fully autonomous vehicles and replaces every public transit ride in the world with them.

[…]

Elon Musk - a man whose “green electric car company” is only profitable thanks to the carbon credits it sells to manufacturers of the dirtiest SUVs in America, without which those planet-killing SUVs would not exist - makes the same mistake. Musk wants to abolish public transit and replace it with EVs […]

Now, both Uber and Musk are both wrong as a matter of simple geometry. Multiply the space occupied by all those AVs by the journeys people in cities need to make by the additional distances of those journeys if we need road for all those cars, and you run out of space.

{ Cory Doctorow | Continue reading }

related { In this work of speculative fiction author Cory Doctorow takes us into a near future where the roads are solely populated by self-driving cars. }

related { Why Uber Still Can’t Make a Profit }

aluminum, acrylic paint, and LCD screen, sound { Tony Oursler [ s~iO. ], 2017 }

economics, motorpsycho, robots & ai | August 17th, 2020 8:22 am

$350,000 […] connected to the home is a 2500 sq ft legitimate jail with 9 cells, booking room and 1/2 bath.

{ flexmls | Continue reading }

household, housing | August 17th, 2020 7:49 am

Mergers-and-acquisitions bankers make lists of companies that should do mergers or acquisitions, equity capital markets bankers make lists of companies that should issue stock, debt capital markets bankers make lists of companies that should issue bonds, etc. Once you have made the lists you get on planes (in normal times) and meet with the companies on the lists to explain to them why they should do mergers or issue stock or whatever. Occasionally they say “hmm you are right we should do a merger” and hire you to do the merger; then you will spend some time actually doing the merger, and you’ll get paid lots of money. But the top of the funnel consists of making lists.

You have to call them and say “hi it would help a lot with your company if you would do a merger.” For that, you need some finance. You need to say “you have a division that is underperforming and if you sold it the rest of your company would be better, so let me sell it for you and take a commission.” Or “there’s this company out there whose CEO wants to retire so you could buy it cheap and it would integrate really well with your widgets business and be accretive to earnings.” Or whatever. The list-making exercise requires some financial analysis. Not a whole ton: This is the top of the funnel, and you do not necessarily need a deep and nuanced understanding of all aspects of the company’s business and competitive landscape in order to come up with some acquisitions and divestitures it could do, though that does help. But, some financial analysis.

This can be creative interesting work, or it can be kind of sterile tedious work; in any case it tends to be unrewarding work, in the sense that if you come up with 100 possible deals and end up executing one of them that’s a pretty good hit rate. A lot of targeting begins with junior bankers making spreadsheets of companies that might be plausible targets based on some crude financial criteria; the senior bankers who have actually met with the companies whittle the spreadsheet down to the realistic targets, and then try to set up meetings with those companies to pitch ideas that still have a low probability of leading to a deal.

What if you could outsource all that work to the companies themselves? What if you built a targeting app that identifies plausible deals based on some crude financial criteria, then sent it to all the companies and said “hey maybe you should do M&A, this app will tell you, if it does then definitely give us a call.” Goldman Sachs Group Inc. has an app now.

{ Bloomberg | Continue reading }

art { Christopher Wool, Untitled, 1992 | Christopher Wool, Hole in Your Fuckin Head, 1992 }

economics | August 16th, 2020 11:56 am

Profits from organized crime are typically passed through legitimate businesses, often exchanging hands several times and crossing borders, until there is no clear trail back to its source—a process known as money laundering.

But with many businesses closed, or seeing smaller revenue streams than usual, hiding money in plain sight by mimicking everyday financial activity became harder. “The money is still coming in but there’s nowhere to put it,” says Isabella Chase, who works on financial crime at RUSI, a UK-based defense and security think tank.

The pandemic has forced criminal gangs to come up with new ways to move money around. In turn, this has upped the stakes for anti-money laundering (AML) teams tasked with detecting suspicious financial transactions and following them back to their source. […]

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, between 2% and 5% of global GDP—between $800 billion and $2 trillion at current figures—is laundered every year. Most goes undetected. Estimates suggest that only around 1% of profits earned by criminals is seized. […] The problem for criminals is that many of the best businesses for laundering money were also those hit hardest by the pandemic. Small shops, restaurants, bars, and clubs are favored because they are cash-heavy, which makes it easier to mix up ill-gotten gains with legal income. […]

Older systems rely on hand-crafted rules, such as that transactions over a certain amount should raise an alert. But these rules lead to many false flags and real criminal transactions get lost in the noise. More recently, machine-learning based approaches try to identify patterns of normal activity and raise flags only when outliers are detected. These are then assessed by humans, who reject or approve the alert.

This feedback can be used to tweak the AI model so that it adjusts itself over time. Some firms, including Featurespace, a firm based in the US and UK that uses machine learning to detect suspicious financial activity, and Napier, another firm that builds machine learning tools for AML, are developing hybrid approaches in which correct alerts generated by an AI can be turned into new rules that shape the overall model.

{ Technology Review | Continue reading }

crime, economics | August 14th, 2020 5:02 pm

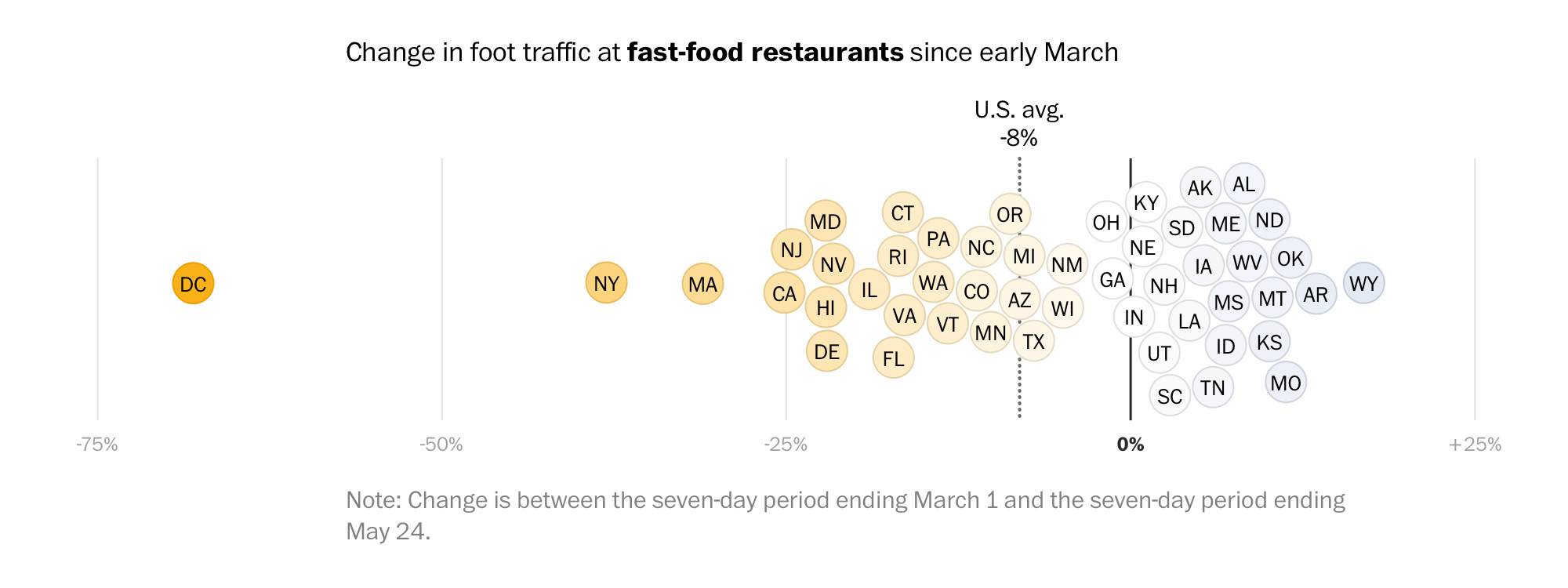

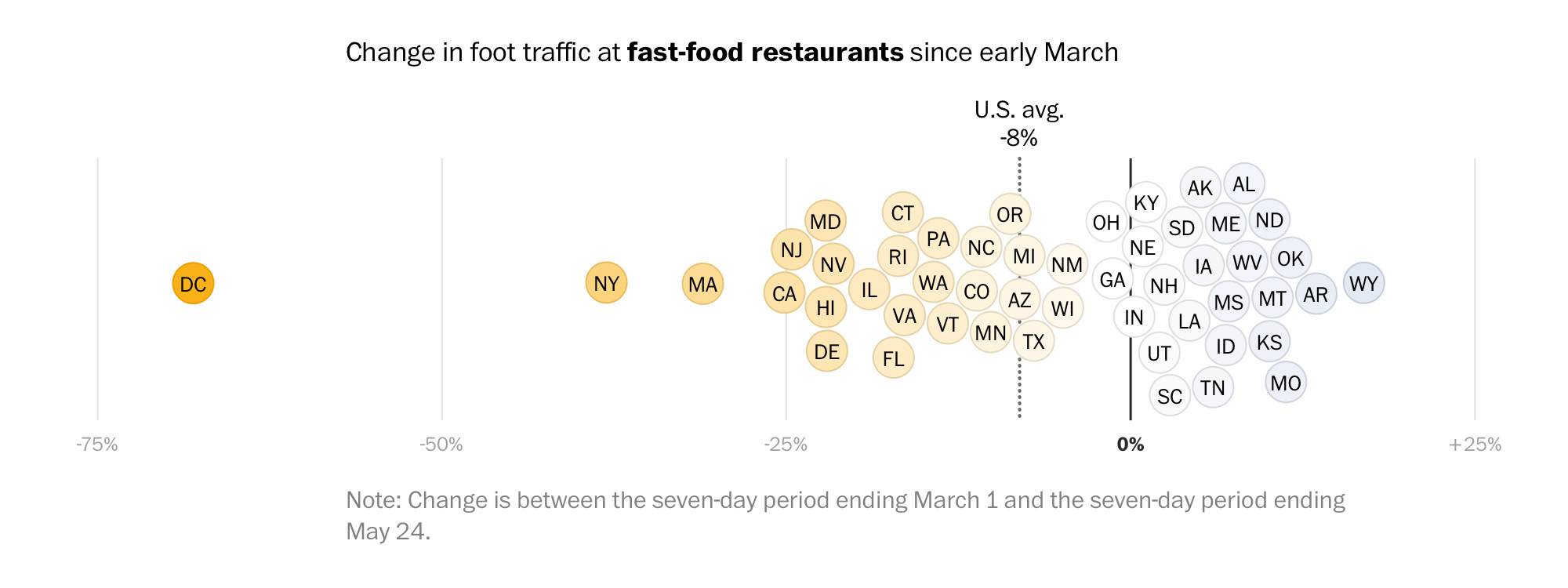

{ In many states, especially in the South and Midwest, traffic at fast-food restaurants is now higher than it was before the restrictions | Washington Post | Continue reading }

economics, food, drinks, restaurants | May 31st, 2020 12:16 pm

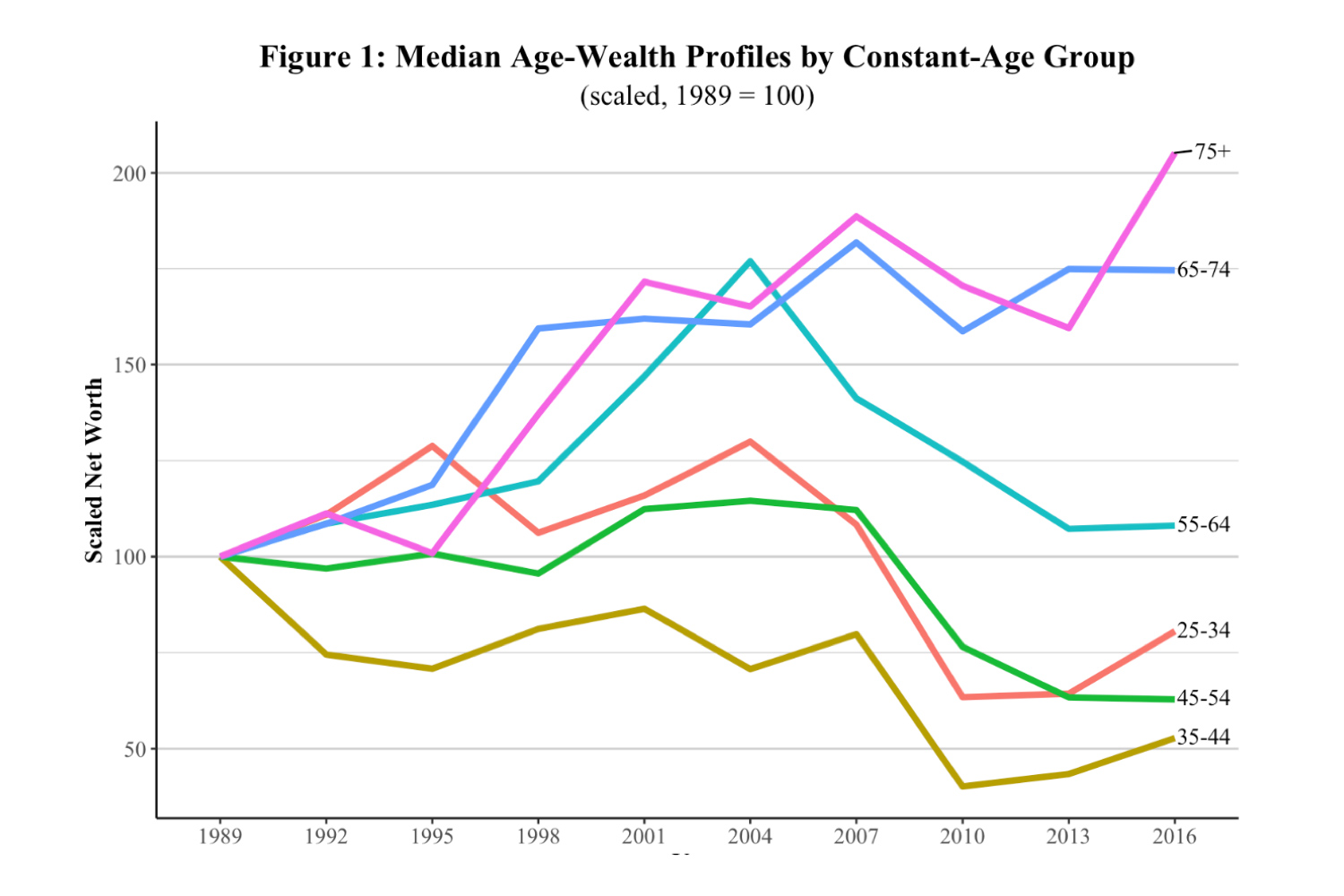

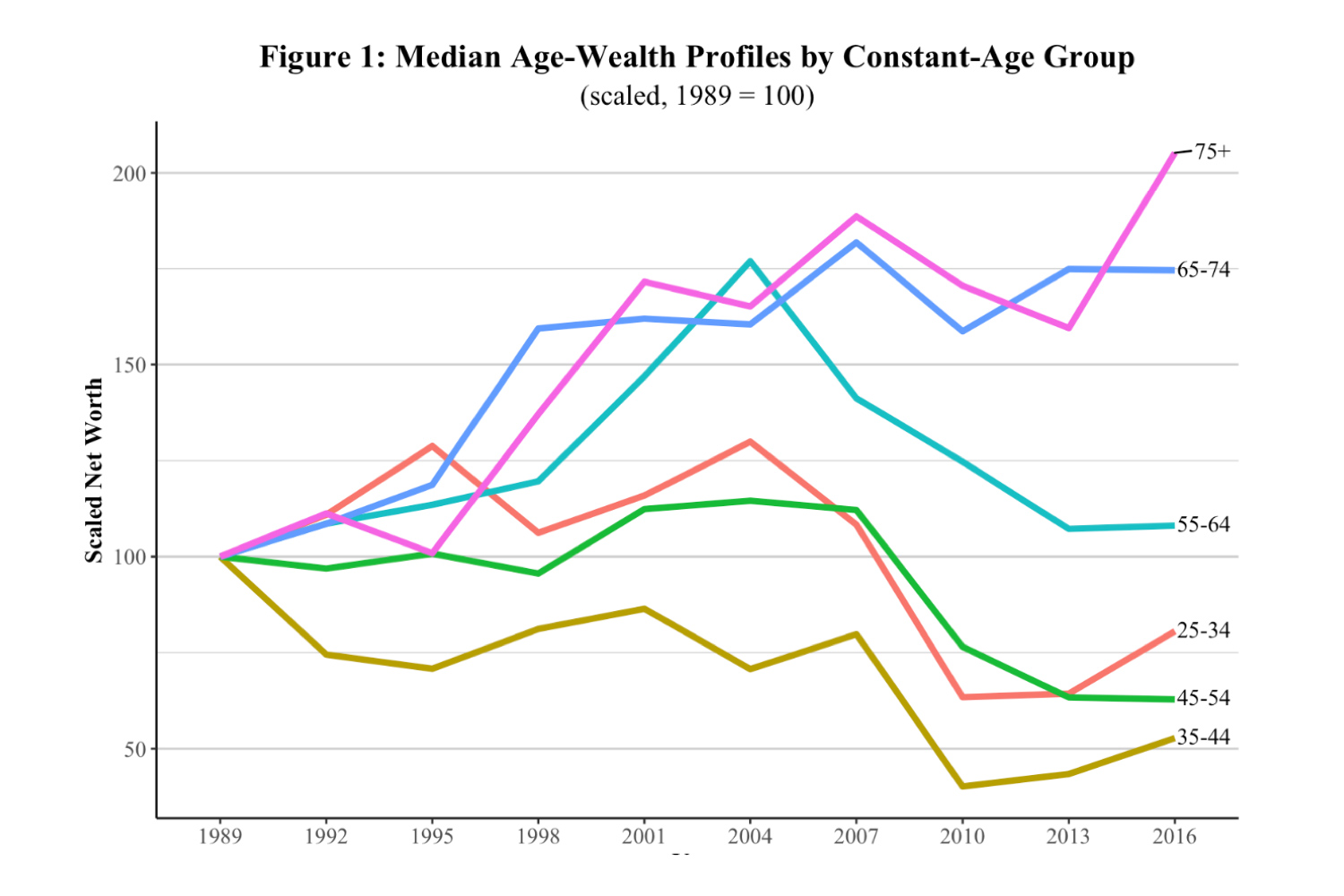

{ While the Great Recession in 2007–2009 reduced wealth in all age groups, the broader long-term trend has been that the wealth of older age groups (65-75+) has increased, while the wealth of successive cross-sections of younger age groups (25-54) has fallen. | Brookings Economic Studies | PDF }

economics | May 29th, 2020 11:27 am

In Germany and China, they already reopened all the stores a month ago. You look at any survey, the restaurants are totally empty. Almost nobody’s buying anything. Everybody’s worried and cautious. And this is in Germany, where unemployment is up by only one percent. Forty percent of Americans have less than $400 in liquid cash saved for an emergency. You think they are going to spend? You’re going to start having food riots soon enough. Look at the luxury stores in New York. They’ve either boarded them up or emptied their shelves, because they’re worried people are going to steal the Chanel bags. The few stores that are open, like my Whole Foods, have security guards both inside and outside. We are one step away from food riots. There are lines three miles long at food banks. That’s what’s happening in America. You’re telling me everything’s going to become normal in three months? That’s lunacy. […]

They just decided Huawei isn’t going to have any access to U.S. semiconductors and technology. We’re imposing total restrictions on the transfer of technology from the U.S. to China and China to the U.S. And if the United States argues that 5G or Huawei is a backdoor to the Chinese government, the tech war will become a trade war. Because tomorrow, every piece of consumer electronics, even your lowly coffee machine or microwave or toaster, is going to have a 5G chip. That’s what the internet of things is about. If the Chinese can listen to you through your smartphone, they can listen to you through your toaster. Once we declare that 5G is going to allow China to listen to our communication, we will also have to ban all household electronics made in China. So, the decoupling is happening. We’re going to have a “splinternet.” It’s only a matter of how much and how fast. […]

I was recently in South Korea. I met the head of Hyundai, the third-largest automaker in the world. He told me that tomorrow, they could convert their factories to run with all robots and no workers. Why don’t they do it? Because they have unions that are powerful. In Korea, you cannot fire these workers, they have lifetime employment. But suppose you take production from a labor-intensive factory in China — in any industry — and move it into a brand-new factory in the United States. You don’t have any legacy workers, any entrenched union. You are going to design that factory to use as few workers as you can. […] But you’re not going to get many jobs. The factory of the future is going to be one person manning 1,000 robots and a second person cleaning the floor. And eventually the guy cleaning the floor is going to be replaced by a Roomba because a Roomba doesn’t ask for benefits or bathroom breaks or get sick and can work 24-7. […]

There’s a conflict between workers and capital. For a decade, workers have been screwed. Now, they’re going to be screwed more. […]

Millions of these small businesses are going to go bankrupt. Half of the restaurants in New York are never going to reopen. How can they survive? They have such tiny margins. Who’s going to survive? The big chains. Retailers. Fast food. The small businesses are going to disappear in the post-coronavirus economy. So there is a fundamental conflict between Wall Street (big banks and big firms) and Main Street (workers and small businesses). And Wall Street is going to win.

{ Nouriel Roubini | NY Mag | Continue reading }

photo { Susan Meiselas, Soldiers search bus passengers along the Northern Highway, El Salvador, 1980 }

The World vs. SARS-CoV-2, economics | May 25th, 2020 6:14 am

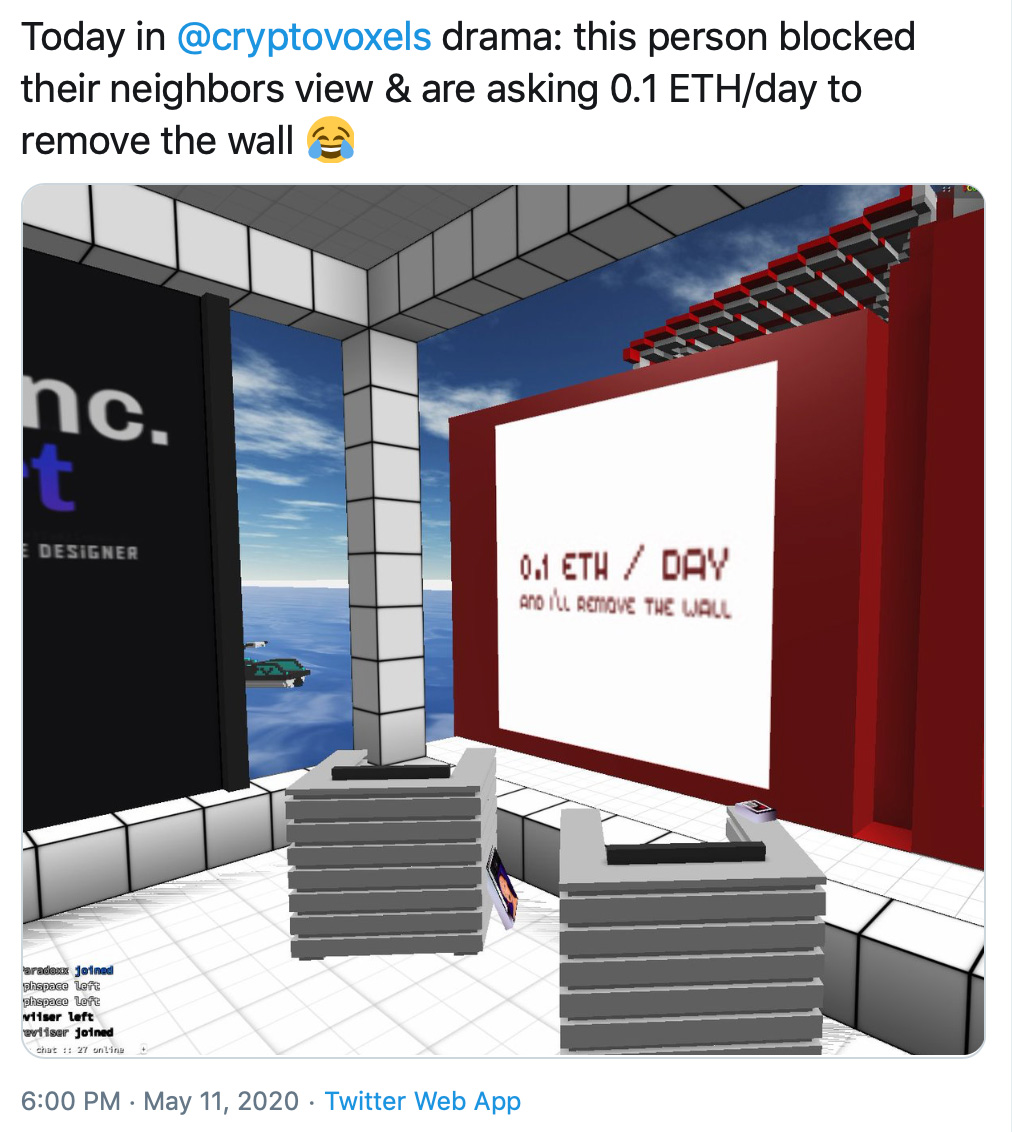

cryptocurrency, haha, law | May 14th, 2020 2:34 pm

Enter Spotify, a platform that is definitely not the answer. In fact, it only exacerbates such conundrums. Yet for now it has manipulated the vast majority of music industry “players” into regarding it as a saving grace. As the world’s largest streaming music company, its network of paying subscribers has risen sharply in recent years, from five million paid subscribers in 2012 to more than sixty million in 2017. Indeed, the platform has now convinced a critical mass that paying $9.99 per month for access to thirty million songs is a solid, even virtuous idea. Every song in the world for less than your shitty airport meal. What could go wrong? […]

Indeed, Spotify’s obsession with mood and activity-based playlists has contributed to all music becoming more like Muzak, a brand that created, programmed, and licensed songs for retail stores throughout the twentieth century. In the 1930s, the company prioritized workplace soundtracks that were meant to heighten productivity, using research to evaluate what listeners responded to most. […]

Spotify playlists work to attract brands and advertisers of all types to the platform. […] We should call this what it is: the automation of selling out. Only it subtracts the part where artists get paid.

{ The Baffler (2017) | Continue reading | Thanks Tim }

economics, music | February 27th, 2020 9:32 am

ExxonMobil, Shell, and Saudi Aramco are ramping up output of plastic—which is made from oil and gas, and their byproducts—to hedge against the possibility that a serious global response to climate change might reduce demand for their fuels, analysts say. Petrochemicals, the category that includes plastic, now account for 14 percent of oil use and are expected to drive half of oil demand growth between now and 2050, the International Energy Agency (IEA) says. The World Economic Forum predicts plastic production will double in the next 20 years.

{ Wired | Continue reading | Thanks Tim }

previously { The missing 99%: why can’t we find the vast majority of ocean plastic? }

photo { Kate Ballis }

economics, gross, oil, photogs | January 22nd, 2020 4:49 pm

The prospect of data-driven ads, linked to expressed preferences by identifiable people, proved in this past decade to be irresistible. From 2010 through 2019, revenue for Facebook has gone from just under $2 billion to $66.5 billion per year, almost all from advertising. Google’s revenue rose from just under $25 billion in 2010 to just over $155 billion in 2019. Neither company’s growth seems in danger of abating.

The damage to a healthy public sphere has been devastating. All that ad money now going to Facebook and Google once found its way to, say, Conde Nast, News Corporation, the Sydney Morning Herald, NBC, the Washington Post, El País, or the Buffalo Evening News. In 2019, more ad revenue flowed to targeted digital ads in the U.S. than radio, television, cable, magazine, and newspaper ads combined for the first time. It won’t be the last time. Not coincidentally, journalists are losing their jobs at a rate not seen since the Great Recession.

Meanwhile, there is growing concern that this sort of precise ad targeting might not work as well as advertisers have assumed. Right now my Facebook page has ads for some products I would not possibly ever desire.

{ Slate | Continue reading | Thanks Tim }

related { Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos says his company is developing a set of laws to regulate facial recognition technology that it plans to share with federal lawmakers. }

economics, marketing, social networks, spy & security | January 12th, 2020 9:03 pm