ideas

Why does AI feel so human if it’s just a “calculator for words”? […]

Most language users are only indirectly aware of the extent to which their interactions are the product of statistical calculations.

Think, for example, about the discomfort of hearing someone say “pepper and salt” rather than “salt and pepper”. Or the odd look you would get if you ordered “powerful tea” rather than “strong tea” at a cafe.

The rules that govern the way we select and order words, and many other sequences in language, come from the frequency of our social encounters with them. The more often you hear something said a certain way, the less viable any alternative will sound.

In linguistics, the vast field dedicated to the study of language, these sequences are known as “collocations”. They’re just one of many phenomena that show how humans calculate multiword patterns based on whether they “feel right” – whether they sound appropriate, natural and human.

{ Science Alert | Continue reading }

Linguistics, robots & ai | September 10th, 2025 3:12 am

Why do philosophers keep debating the same big questions—about free will, morality, knowledge, and political authority—without ever settling them? This piece explores several possible answers. Maybe philosophy makes progress by spinning off answerable questions into the sciences. Maybe some problems are just too hard for minds like ours. Or maybe the trouble lies in language: our concepts are vague, our disagreements often verbal, or the questions themselves may be confused. […]

I suggest that philosophy’s value doesn’t lie in delivering final answers, but in helping us clarify our assumptions, explore alternatives, and better understand the questions that matter most, even when we can’t resolve them.

{ Michael Hannon | Continue reading }

ideas | August 7th, 2025 8:17 am

While the free will debate tends to focus primarily on the implications of determinism for freedom, a long line of philosophers have also argued that free will would not be compatible with indeterminism either. These arguments typically take the form of a so-called Luck Objection: a family of related arguments which all seek to show, roughly, that if an action is not causally pre-determined then it must be a sort of random happening, over which the agent lacks the control required for free will. […]

We develop an empirically plausible model of agential decision-making and apply this to the problem of luck. We argue that, under such a model, it is entirely natural to think of an agent’s actions as both ‘undetermined’ (in the sense of being under-determined) and under their own control.

{ Chance, Choice, and Control: Free Will in an Indeterministic Universe | Continue reading }

ideas | July 31st, 2025 7:39 am

An artificial intelligence firm downloaded for free millions of copyrighted books in digital form from pirate sites on the internet. The firm also purchased copyrighted books (some overlapping with those acquired from the pirate sites), tore off the bindings, scanned every page, and stored them in digitized, searchable files. All the foregoing was done to amass a central library of “all the books in the world” to retain “forever.”

From this central library, the AI firm selected various sets and subsets of digitized books to train various large language models under development to power its AI services. Some of these books were written by plaintiff authors, who now sue for copyright infringement.

[…]

Defendant Anthropic PBC is an AI software firm founded by former OpenAI employees in January 2021. Its core offering is an AI software service called Claude. When a user prompts Claude with text, Claude quickly responds with text — mimicking human reading and writing. Claude can do so because Anthropic trained Claude — or rather trained large language models or LLMs underlying various versions of Claude — using books and other texts selected from a central library Anthropic had assembled. Claude was first released publicly in March 2023. Seven successive versions of Claude have been released since. Users may ask Claude some questions for free. Demanding users and corporate clients pay to use Claude, generating over one billion dollars in annual revenue.

[…]

This order grants summary judgment for Anthropic that the training use was a fair use. And, it grants that the print-to-digital format change was a fair use for a different reason. But it denies summary judgment for Anthropic that the pirated library copies must be treated as training copies.

We will have a trial on the pirated copies used to create Anthropic’s central library and the resulting damages, actual or statutory (including for willfulness). That Anthropic later bought a copy of a book it earlier stole off the internet will not absolve it of liability for the theft but it may affect the extent of statutory damages. Nothing is foreclosed as to any other copies flowing from library copies for uses other than for training LLMs.

{ Judge rules Anthropic training on books it purchased was “fair use,” but not for the ones it stole | United States District Court, Northern District of California | Full Order | PDF }

books, law, robots & ai | June 25th, 2025 4:41 am

Tomorrow’s US military must approach warfighting with an alternate mindset that is prepared to leverage all elements of national power to influence the ideological spheres of future enemies by engaging them with alternate means—memes—to gain advantage.

{ MEMETICS—A GROWTH INDUSTRY IN US MILITARY OPERATIONS | PDF }

fights, marketing, media, strategy | May 18th, 2025 11:13 am

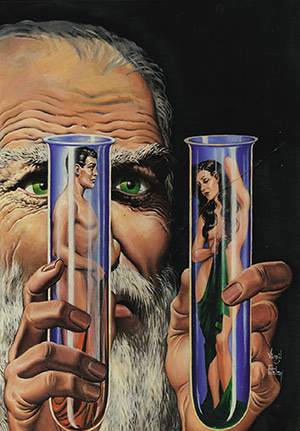

psychologists were grappling with how to define and measure creativity in humans. The prevailing theory—that creativity was a product of intelligence and high IQ—was fading, but psychologists weren’t sure what to replace it with. The Dartmouth organizers had one of their own. “The difference between creative thinking and unimaginative competent thinking lies in the injection of some randomness,” they wrote, adding that such randomness “must be guided by intuition to be efficient.”

Nearly 70 years later, following a number of boom-and-bust cycles in the field, we now have AI models that more or less follow that recipe. While large language models that generate text have exploded in the last three years, a different type of AI, based on what are called diffusion models, is having an unprecedented impact on creative domains. By transforming random noise into coherent patterns, diffusion models can generate new images, videos, or speech, guided by text prompts or other input data. The best ones can create outputs indistinguishable from the work of people, as well as bizarre, surreal results that feel distinctly nonhuman.

Now these models are marching into a creative field that is arguably more vulnerable to disruption than any other: music. AI-generated creative works—from orchestra performances to heavy metal—are poised to suffuse our lives more thoroughly than any other product of AI has done yet. The songs are likely to blend into our streaming […]

Music models can now create songs capable of eliciting real emotional responses, presenting a stark example of how difficult it’s becoming to define authorship and originality in the age of AI.

The courts are actively grappling with this murky territory. Major record labels are suing the top AI music generators, alleging that diffusion models do little more than replicate human art without compensation to artists. The model makers counter that their tools are made to assist in human creation.

In deciding who is right, we’re forced to think hard about our own human creativity. Is creativity, whether in artificial neural networks or biological ones, merely the result of vast statistical learning and drawn connections, with a sprinkling of randomness? If so, then authorship is a slippery concept. If not—if there is some distinctly human element to creativity—what is it? […]

We can first divide the human creative process into phases, including an ideation or proposal step, followed by a more critical and evaluative step that looks for merit in ideas. A leading theory on what guides these two phases is called the associative theory of creativity, which posits that the most creative people can form novel connections between distant concepts. […] For example, the word apocalypse is more closely related to nuclear power than to celebration. Studies have shown that highly creative people may perceive very semantically distinct concepts as close together. Artists have been found to generate word associations across greater distances than non-artists. […]

A new study, led by researchers at Harvard Medical School and published in February, suggests that creativity might even involve the suppression of particular brain networks, like ones involved in self-censorship.

{ Technology Review | Continue reading }

Ask any creativity expert today what they mean by “creativity,” and they’ll tell you it’s the ability to generate something new and useful. That something could be an idea, a product, an academic paper—whatever. But the focus on novelty has remained an aspect of creativity from the beginning. It’s also what distinguishes it from other similar words, like imagination or cleverness. […]

The kinds of LLMs that Silicon Valley companies have put forward are meant to appear “creative” in those conventional senses. Now, whether or not their products are meaningful or wise in a deeper sense, that’s another question. If we’re talking about art, I happen to think embodiment is an important element. Nerve endings, hormones, social instincts, morality, intellectual honesty—those are not things essential to “creativity” necessarily, but they are essential to putting things out into the world that are good, and maybe even beautiful in a certain antiquated sense. That’s why I think the question of “Can machines be ‘truly creative’?” is not that interesting, but the questions of “Can they be wise, honest, caring?” are more important if we’re going to be welcoming them into our lives as advisors and assistants.

{ Technology Review | Continue reading }

ideas, music, robots & ai | May 18th, 2025 7:21 am

In Plato’s dialogue Symposium, seven varied speeches are made on the meaning of love at an all-male drinking party set in ancient Athens in 416 BCE. One of the participants is the philosopher Socrates, and when it comes to his turn to speak, he is made to say something surprising: he proposes to ‘tell the truth’ about love. It’s surprising because in other Platonic dialogues, where Socrates addresses questions such as ‘What is knowledge?’, ‘What is excellence?’, and ‘What is courage?’, he has no positive answers to give about these central areas of human thought and experience: in fact, Socrates was well known for having laid no claim to knowledge, and for asserting that ‘the only thing I know is that I do not know’. How is it, then, that Socrates can claim to know the truth about something as fundamental and potentially all-encompassing as love?

The answer is that, in the Symposium, Socrates claims to know the truth only because he learned it from someone else. […]

The doctrine Socrates attributes to Diotima in the Symposium is that love – or, more precisely, the divine spirit Eros – operates on various levels. At the lowest level, love engenders erotic feelings towards the body of someone to whom one is attracted. However, what attracts us about that body is, Diotima says, a quality that we call its ‘beauty’, which in turn leads to a recognition that many other bodies possess this quality and are equally capable of inspiring erotic feelings. By recognising the presence of beauty in many bodies, one comes to understand that what is attractive to us is not the bodies themselves, but the abstract quality of beauty of which the bodies partake. […]

according to Diotima, the commonplace erotic desire that we feel towards a person we consider to be beautiful can lead us up the ‘ladder’ of love, rung by rung, ascending from the particular object of desire to a general appreciation of the abstract quality of beauty and, beyond that, to moral goodness. What begins as physical lust is ennobled by the way it encourages the lover to mount upwards to the highest goodness imaginable, the abstract ‘form of the good’.

{ Aeon | Continue reading }

ideas, relationships | April 23rd, 2025 7:24 am

SIMON: We have free will in the sense that our resulting behavior will depend on who we are and the situation we are in. People respond differently when confronting the same situation.

BORGES: So, when faced with a situation in which there is a choice to be made between two possible behaviors, we can choose one of them?

SIMON: Your mental programming does the choosing.

It seems to me that Simon is here arguing for what philosophers call “compatibilism” — the idea that determinism can coexist with meaningful human choice and responsibility.

[…]

BORGES: Now, does this account for all of our actions? That is, if my right hand is resting on my left hand, is it because it has to be this way? I believe people do quite a lot of things without any thinking.

SIMON: That’s the doing of our subconscious mind. […] that’s because we are heavily programmed. […] when we study a person who is in the process of solving a problem, we start from the assumption that every little thing has a cause. We are not always able to identify those causes.

{ When Jorge Luis Borges met one of the founders of AI | Continue reading }

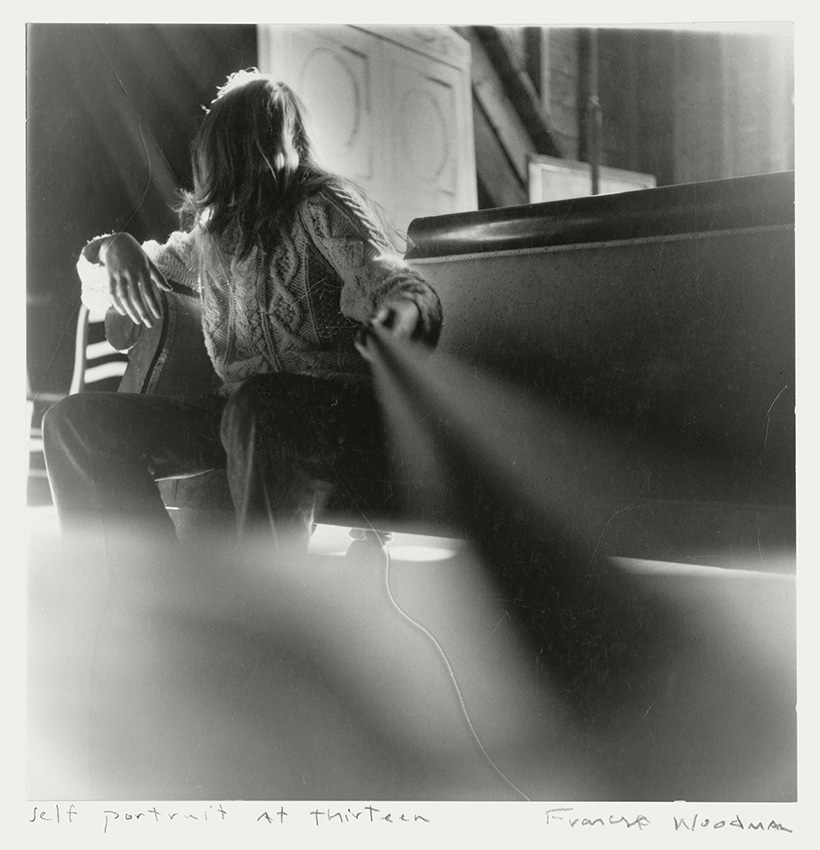

oil and charcoal on linen { Chris Ofili, Iscariot Blues, 2006 }

ideas | April 12th, 2025 10:13 am

The rape of the Sabine women, also known as the abduction of the Sabine women, was an incident in the legendary history of Rome in which the men of Rome committed bride kidnappings or mass abduction for the purpose of marriage, of women from other cities in the region. It has been a frequent subject of painters and sculptors, particularly since the Renaissance.

The word “rape” is the conventional translation of the Latin word raptio used in the ancient accounts of the incident. The Latin word means “taking”, “abduction” or “kidnapping”, but when used with women as its object, sexual assault is usually implied. […]

According to Roman historian Livy, the abduction of Sabine women occurred in the early history of Rome shortly after its founding in the mid-8th century BC and was perpetrated by Romulus [legendary founder and first king of Rome] and his predominantly male followers; it is said that after the foundation of the city, the population consisted solely of Latins and other Italic peoples, in particular male bandits. With Rome growing at such a steady rate in comparison to its neighbors, Romulus became concerned with maintaining the city’s strength. His main concern was that with few women inhabitants there would be no chance of sustaining the city’s population, without which Rome might not last longer than a generation. On the advice of the Senate, the Romans then set out into the surrounding regions in search of wives to establish families with. The Romans negotiated unsuccessfully with all the peoples that they appealed to, including the Sabines, who populated the neighboring areas. […]

The Romans devised a plan to abduct the Sabine women during the festival of Neptune Equester. They planned and announced a festival of games to attract people from all the nearby towns. At the festival, […] the Romans grabbed the Sabine women and fought off the Sabine men. […] All of the women abducted at the festival were said to have been virgins except for one married woman, Hersilia, who became Romulus’s wife and would later be the one to intervene and stop the ensuing war between the Romans and the Sabines.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Linguistics, crime, flashback | March 1st, 2025 3:47 am

Spending time alone is a virtually inevitable part of daily life that can promote or undermine well-being.

Here, we explore how the language used to describe time alone—such as “me-time” “solitude,” or “isolation”—influences how it is perceived and experienced […]

linguistic framing affected what people thought about, but not what they did, while alone […]

simple linguistic shifts may enhance subjective experiences of time alone

{ PsyArXiv | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | November 4th, 2024 12:56 pm

It begins each day at nightfall. As the light disappears, billions of zooplankton, crustaceans and other marine organisms rise to the ocean surface to feed on microscopic algae, returning to the depths at sunrise. The waste from this frenzy – Earth’s largest migration of creatures – sinks to the ocean floor, removing millions of tonnes of carbon from the atmosphere each year.

This activity is one of thousands of natural processes that regulate the Earth’s climate. Together, the planet’s oceans, forests, soils and other natural carbon sinks absorb about half of all human emissions. […]

Findings by an international team of researchers show the amount of carbon absorbed in 2023 by land has temporarily collapsed. The final result was that forest, plants and soil – as a net category – absorbed almost no carbon.

There are warning signs at sea, too. Greenland’s glaciers and Arctic ice sheets are melting faster than expected, which is disrupting the Gulf Stream ocean current and slows the rate at which oceans absorb carbon. For the algae-eating zooplankton, melting sea ice is exposing them to more sunlight – a shift scientists say could keep them in the depths for longer, disrupting the vertical migration that stores carbon on the ocean floor.

{ Guardian | Continue reading }

climate, elements, eschatology, incidents | October 15th, 2024 7:07 am

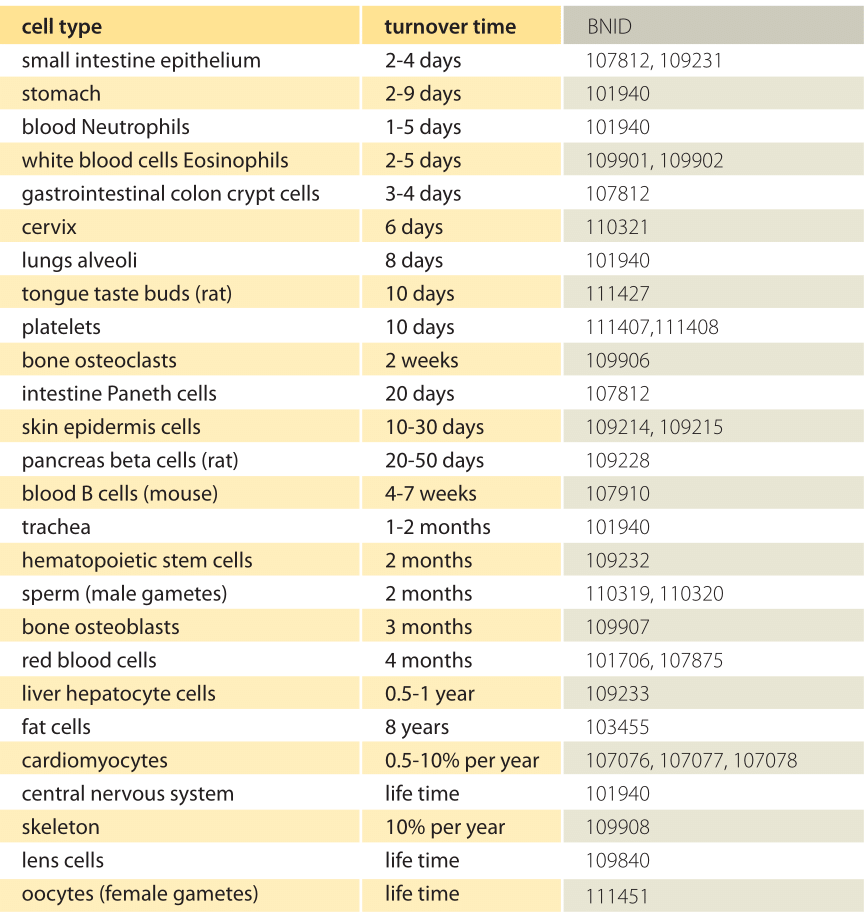

health, psychology, time | September 24th, 2024 5:47 am

I have just now come from a party where I was its life and soul; witticisms streamed from my lips, everyone laughed and admired me, but I went away — yes, the dash should be as long as the radius of the earth’s orbit ——————————— and wanted to shoot myself.

{ Søren Kierkegaard, Journal, March 1836 | Continue reading }

experience, ideas | May 10th, 2024 4:54 am

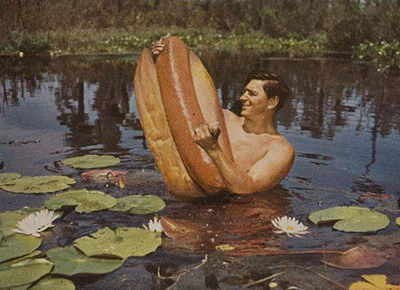

Do you surf yourself?

No, I tried. I did it for about a week, 20 years ago. You have to dedicate yourself to these great things. And I don’t believe in being good at a lot of things—or even more than one. But I love to watch it. I think if I get a chance to be human again, I would do just that. You wake up in the morning and you paddle out. You make whatever little money you need to survive. That seems like the greatest life to me.

Or you could become very wealthy in early middle-age, stop doing the hard stuff, and go off and become a surfer.

No, no. You want to be broke. You want it to be all you’ve got. That’s when life is great. People are always trying to add more stuff to life. Reduce it to simpler, pure moments. That’s the golden way of living, I think.

{ Jerry Seinfeld | GQ | Continue reading }

related { Anecdote on Lowering the work ethic }

eudaemonism, sport | April 22nd, 2024 12:31 pm

Any viral post on X now almost certainly includes A.I.-generated replies, from summaries of the original post to reactions written in ChatGPT’s bland Wikipedia-voice, all to farm for follows. Instagram is filling up with A.I.-generated models, Spotify with A.I.-generated songs. Publish a book? Soon after, on Amazon there will often appear A.I.-generated “workbooks” for sale that supposedly accompany your book (which are incorrect in their content; I know because this happened to me). Top Google search results are now often A.I.-generated images or articles. Major media outlets like Sports Illustrated have been creating A.I.-generated articles attributed to equally fake author profiles. Marketers who sell search engine optimization methods openly brag about using A.I. to create thousands of spammed articles to steal traffic from competitors.

Then there is the growing use of generative A.I. to scale the creation of cheap synthetic videos for children on YouTube. Some example outputs are Lovecraftian horrors, like music videos about parrots in which the birds have eyes within eyes, beaks within beaks, morphing unfathomably while singing in an artificial voice, “The parrot in the tree says hello, hello!” The narratives make no sense, characters appear and disappear randomly, and basic facts like the names of shapes are wrong. After I identified a number of such suspicious channels on my newsletter, The Intrinsic Perspective, Wired found evidence of generative A.I. use in the production pipelines of some accounts with hundreds of thousands or even millions of subscribers. […]

There’s so much synthetic garbage on the internet now that A.I. companies and researchers are themselves worried, not about the health of the culture, but about what’s going to happen with their models. As A.I. capabilities ramped up in 2022, I wrote on the risk of culture’s becoming so inundated with A.I. creations that when future A.I.s are trained, the previous A.I. output will leak into the training set, leading to a future of copies of copies of copies, as content became ever more stereotyped and predictable.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

and { When Marie was first approached by Arcads in December 2023, the company explained they were seeking test subjects to see whether they could turn someone’s voice and likeness into AI. […] Marie doesn’t worry that by giving up her rights to an AI company, she’s bringing about the end of her work—as many actors fear. […] Hyperrealistic deepfakes and AI-generated content have rapidly saturated our digital lives. The impact of this ‘hidden in plain sight’ dynamic is increasing distrust of all digital media—that anything could be faked. }

eschatology, robots & ai | March 30th, 2024 6:18 am

At 40, Franz Kafka (1883-1924), who never married and had no children, was walking through a park one day in Berlin when he met a girl who was crying because she had lost her favourite doll. She and Kafka searched for the doll unsuccessfully. Kafka told her to meet him there the next day and they would come back to look for her.

The next day, when they had not yet found the doll, Kafka gave the girl a letter “written” by the doll saying “please don’t cry. I took a trip to see the world. I will write to you about my adventures.” Thus began a story which continued until the end of Kafka’s life.

During their meetings, Kafka read the letters of the doll carefully written with adventures and conversations that the girl found adorable. Finally, Kafka brought back the doll (he bought one) that had returned to Berlin.

“It doesn’t look like my doll at all,” said the girl. Kafka handed her another letter in which the doll wrote: “my travels have changed me.” The little girl hugged the new doll and brought the doll with her to her happy home. A year later Kafka died. Many years later, the now-adult girl found a letter inside the doll. In the tiny letter signed by Kafka it was written: “Everything you love will probably be lost, but in the end, love will return in another way.”

{ Avi | a true anecdote, unproven }

books, kids, toys | February 14th, 2024 7:03 am

For a quarter century, Gerry Fialka, an experimental film-maker from Venice, California, has hosted a book club devoted to a single text: James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, one of the most famously difficult texts in literary history.

Starting in 1995, between 10 and 30 people would show up to monthly meetings at a local library. At first they read two pages a month, eventually slowing to just one page per discussion. At that pace, the group – which now meets on Zoom – reached the final page in October. It took them 28 years. […]

This November, they started back on page three.

“There is no next book,” Fialka told me. “We’re only reading one book. Forever.”

{ The Guardian | Continue reading }

Finnegans Wake was first published in 1939 and it is widely regarded as being one of the most challenging novels in English literature.

Written in a torrent of idiosyncratic language over more than 600 pages, it includes made-up words in several languages, puns and arcane allusions to Greek mythology.

{ The Times | Continue reading }

The club is among several around the world devoted to collectively untangling the meaning of Joyce’s 1939 novel, which tells many stories simultaneously, and is dense with neologisms and allusions. Critics have considered the work perplexing; a review in The New Yorker suggested it might have been written by a “god, talking in his sleep.” […]

Margot Norris, a professor emerita of English at the University of California, Irvine, and a Joyce scholar, described “Finnegans Wake” as “dramatic poetry” that instead of following a typical plot plays with the very nature of language. “We get words in ‘Finnegans Wake’ that aren’t words,” Dr. Norris said, referring to a passage of seemingly nonsense phrases: “This is Roo- shious balls. This is a ttrinch. This is mistletropes. This is Canon Futter with the popynose.” The novel, she added, “draws your attention to language, but the language isn’t going to be exactly the language that you know.” […]

“People think they’re reading a book, they’re not,” he said. “They’re breathing and living together as human beings in a room; looking at printed matter, and figuring out what printed matter does to us.”

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

previously { Joyce invented a unique polyglot-language or idioglossia solely for the purpose of this work. }

James Joyce | December 8th, 2023 2:17 pm

On 25 October 1946, Karl Popper (at the London School of Economics), was invited to present a paper entitled “Are There Philosophical Problems?” at a meeting of the Cambridge University Moral Sciences Club, which was chaired by Ludwig Wittgenstein.

The two started arguing vehemently over whether there existed substantial problems in philosophy, or merely linguistic puzzles—the position taken by Wittgenstein.

Wittgenstein used a fireplace poker to emphasize his points, gesturing with it as the argument grew more heated. Eventually, Wittgenstein claimed that philosophical problems were nonexistent.

In response, Popper claimed there were many issues in philosophy, such as setting a basis for moral guidelines. Wittgenstein then thrust the poker at Popper, challenging him to give any example of a moral rule, Popper (later) claimed to have said:

“Not to threaten visiting lecturers with pokers”

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Parnet: Let’s move on to “W”.

Deleuze: There’s nothing in “W”.

Parnet: Yes, there’s Wittgenstein. I know he’s nothing for you, but it’s only a word.

Deleuze: I don’t like to talk about that… For me, it’s a philosophical catastrophe. It’s the very example of a “school”, it’s a regression of all philosophy, a massive regression. […] They imposed a system of terror in which, under the pretext of doing something new, it’s poverty instituted in all grandeur… […] the Wittgensteinians are mean and destructive. […] They are assassins of philosophy.

{ The Deleuze Seminars | Continue reading }

buffoons, controversy, fights, ideas | October 15th, 2023 10:03 am

Sartre, it will be recalled, had asserted a kind of absolute freedom for the conscious human being. It was this claim that Merleau-Ponty disputed. […] If freedom were everywhere, as seemed to be the case in Sartre’s Being and Nothingness , then freedom in effect would be nowhere […] “Free action, in order to be discernible, has to stand out from a background of life from which it is entirely, or almost entirely, absent.” (Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, 1945) […]

While Sartre properly emphasized the subject’s freedom, he distorted the scope of this freedom by rendering it absolute. The subject, argued Merleau-Ponty, always faced a previously established situation, an environment and world not of its own making. Its life, as intersubjectively open, acquired a social atmosphere which it did not itself constitute. Social roles pressed upon the individual as plausible courses for his life to take. Certain modes of behavior became habitual. Probably , this world, these habits, a familiar comportment: probably these would not change overnight. It was unlikely that an individual would suddenly choose to be something radically other than what he had already become. The Sartre of Being and Nothingness underestimated the weight of this realm of relative constraint and habitual inertia.

{ Merleau-Ponty: The Ambiguity of History | Continue reading

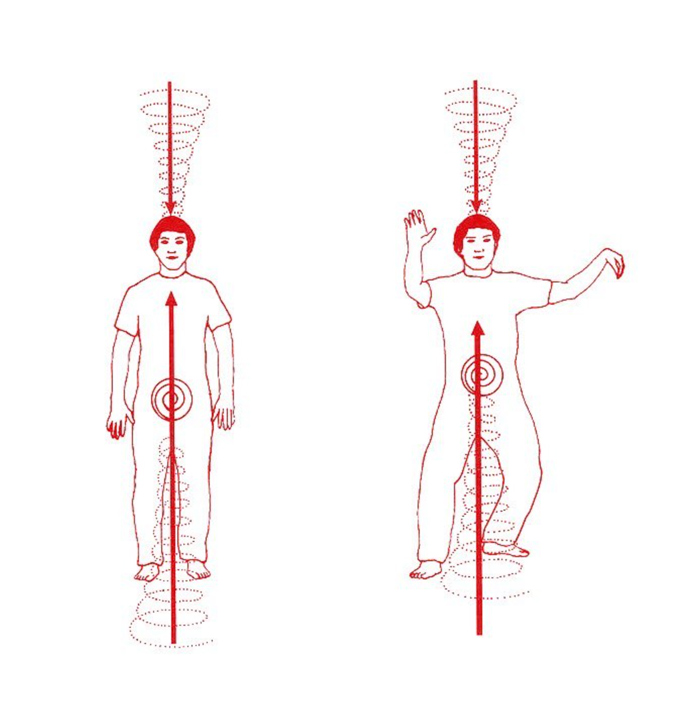

Cognitive science is lacking conceptual tools to describe how an agent’s motivations, as such, can play a role in the generation of its behavior. […] a new kind of non-reductive theory is proposed: Irruption Theory. […] irruptions are associated with increased unpredictability of (neuro)physiological activity, and they should hence be quantifiable in terms of information-theoretic entropy. Accordingly, evidence that action, cognition, and consciousness are linked to higher levels of neural entropy can be interpreted as indicating higher levels of motivated agential involvement.

{ PsyArXiv | Continue reading }

controversy, ideas, theory | April 27th, 2023 6:35 am

Humans can think about possible states of the world without believing in them, an important capacity for high-level cognition.

Here we use fMRI and a novel “shell game” task to test two competing theories about the nature of belief and its neural basis.

According to the Cartesian theory, information is first understood, then assessed for veracity, and ultimately encoded as either believed or not believed. According to the Spinozan theory, comprehension entails belief by default, such that understanding without believing requires an additional process of “unbelieving”. […]

findings are consistent with a version of the Spinozan theory whereby unbelieving is an inhibitory control process.

{ PsyArXiv | Continue reading }

neurosciences, spinoza | June 22nd, 2022 11:07 am

Inside, Mr. Pierrat found a literary treasure trove: long-lost manuscripts by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, the acclaimed but equally reviled French author who wrote classics like “Journey to the End of the Night,” published in 1932, as well as virulently antisemitic tracts. […] Céline always maintained that the manuscripts had been stolen from his Paris apartment after he escaped to Germany in 1944, fearing that he would be punished as a collaborator when the Allies liberated the city. […] David Alliot, a literary researcher, said the issue for many French was that while Céline was a “literary genius,” he was a deeply flawed human being. […]

Mr. Thibaudat said he was given the manuscripts by an undisclosed benefactor, or benefactors — he declined to elaborate — about 15 years ago. But he had kept the stash secret, waiting for Céline’s widow to die, at the request of the benefactor, whose wish was that an “antisemitic family” would not profit from the trove, he said in an interview. […]

the manuscripts includes the complete version of the novel “Casse-pipe,” partly published in 1949, and a previously unknown novel titled “Londres” […]

With his lawyer by his side, Mr. Thibaudat met Céline’s heirs in June 2020. It did not go well. Mr. Thibaudat suggested that the manuscripts be given to a public institution to make them accessible to researchers. François Gibault, 89, and Véronique Chovin, 69, the heirs to Céline’s work through their connections as friends to the family, were outraged, and sued Mr. Thibaudat, demanding compensation for years of lost revenues.

“Fifteen years of non-exploitation of such books is worth millions of euros,” said Jérémie Assous, the lawyer and longtime friend of Céline’s heirs. “He’s not protecting his source, he’s protecting a thief.”

In July, Mr. Thibaudat finally handed over the manuscripts on the orders of prosecutors. During a four-hour interview with the police, Mr. Thibaudat refused to name his source. The investigation is continuing.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

books, economics | October 26th, 2021 12:48 pm

In building your book I wanted to pursue my own process of decomposition. I began to think about the ways in which paper degrades. Rotting in the ground, exposure to rain, chemicals (I used Xylene, a paint thinner, for the image transfers on the cover), and fire. Although rain or burying paper in the ground would have created unique and unpredictable patterns of ruin in the paper, these seemed like passive processes, whereas burning paper could achieve some level of stochastic design but in a more involved, active, and risk-exposed situation. I followed the traditional recipe for Chinese blackpowder: 75% potassium nitrate, or saltpeter, 15% carbon, 10% sulphur. […]

On a hot plate, outside, the potassium nitrate is usually dissolved in a pot of water, however instead of water I poured into the potassium nitrate a jar of my stale, sunbaked urine since it accelerates the burn process.

{ Big Other | Continue reading }

books, chem | June 24th, 2021 10:36 am

Canada, one of the most real estate-obsessed nations on earth — and one of the least affected by the 2008 crash — is up 42+% in the past year alone.

Even in Ethiopia, where my wife grew up, a three-bedroom detached house in the capital can cost you $1+ million USD.

Until recently, most people’s house price paradigm looked something like this:

A house’s market price is the maximum amount that a buyer can expect to afford over the next 25–40 years. But because wages are flatlined and purchasing parity is the same as in 1978, the only rational explanation for this current price explosion is a giant debt bubble.

But what if the paradigm — the baseline assumption of what dictates house prices — is changing?

What if the newly-redefined value of shelter is the maximum amount of annual rent that can be extracted per unit of housing? […]

As reader Valerie Kittell put it: “Airbnb-type models altered the market irreversibly by proving on a large scale that short term rentals were more lucrative than stable long-term residents.”

We’re in the middle of a paradigm shift to corporate serfdom.

Stop enriching corrupt banks — pay off your mortgages and never look back. Parents and grandparents with means: Help your kids get a start in housing before it’s out of their reach forever.

{ Jared A. Brock | Continue reading }

housing, theory | June 18th, 2021 8:16 am

In 2008, the report warned about the potential emergence of a pandemic originating in East Asia and spreading rapidly around the world.

The latest report, Global Trends 2040, [was] released last week […] “Large segments of the global population are becoming wary of institutions and governments that they see as unwilling or unable to address their needs.” […] Experts in Washington who have read these reports said they do not recall a gloomier one.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

art { Günter Fruhtrunk, Rote Vibration, 1970 | Bridget Riley, Ra, 1981 }

eschatology | April 16th, 2021 12:14 am

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838) is the only complete novel written by American writer Edgar Allan Poe. […] The story starts out as a fairly conventional adventure at sea, but it becomes increasingly strange and hard to classify. […]

Peters, Pym, and Augustus hatch a plan to seize control of the ship […] soon the three men are masters of the Grampus: all the mutineers are killed or thrown overboard except one, Richard Parker, whom they spare to help them run the vessel. […] As time passes, with no sign of land or other ships, Parker suggests that one of them should be killed as food for the others. They draw straws, following the custom of the sea, and Parker is sacrificed.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

On 19 May 1884 four men set sail from Southampton in a small yacht. They were professional sailors tasked with taking their vessel, the Mignonette, to its new owner in Australia. […] The Mignonette’s captain, Tom Dudley, was 31 years old and a proven yachtsman. Of his crew, Ned Brooks and mate Edwin Stephens were likewise seasoned sailors. The final crew-member, cabin boy Richard Parker, was just 17 years old and making his first voyage on the open sea. […]

On 5 July, sailing from Madeira to Cape Town, the Mignonette was sunk by a giant wave. […] Adrift in an open boat in the South Atlantic, hundreds of miles from land, they had little in the way of provisions. They had no water, and for food, only two 1lb tins of turnips grabbed during the Mignonette’s final moments.

Over the next 12 days, these turnips were scrupulously rationed out […] For water […] they resorted to drinking their own urine, although this too was a diminishing resource as their bodies became increasingly dehydrated.

By 17 July all supplies on board the little dinghy had been exhausted. After a further three days, the inexperienced Richard Parker could not resist gulping down sea water in an attempt to allay his thirst. It is now known that small quantities of sea water can help to sustain life in survival situations, but in that period it was widely believed to be fatal. Parker also drank far in excess of modern recommendations and he was soon violently unwell, collapsing in the bottom of the boat with diarrhea.

Even before Parker fell ill, Tom Dudley had broached the fearful topic of the “custom of the sea,” the practice of drawing lots to select a sacrificial victim who could be consumed by his crew-mates. […] According to their subsequent depositions, however, no lots were drawn. Instead, Dudley told Stephens to hold Parker’s legs should he struggle, before kneeling and thrusting his penknife into the boy’s jugular. […] Parker’s body was then stripped and butchered. The heart and liver were eaten immediately; strips of flesh were cut from his limbs and set aside as future rations. What remained of the young man was heaved overboard.

{ History Extra | Continue reading }

books, flashback, mystery and paranormal | March 27th, 2021 4:44 am

eschatology | March 5th, 2021 2:02 pm

Speakers take a lot for granted. That is, they presuppose information. As we wrote this, we presupposed that readers would understand English. We also presupposed as we wrote the last sentence, repeated in (1), that there was a time when we wrote it, for otherwise the fronted phrase “as we wrote this” would not have identified a time interval.

(1) As we wrote this, we presupposed that readers would understand English.

Further, we presupposed that the sentence was jointly authored, for otherwise “we” would not have referred. And we presupposed that readers would be able to identify the reference of “this”, i.e., the article itself. And we presupposed that there would be at least two readers, for otherwise the bare plural “readers” would have been inappropriate. And so on.

{ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy | Continue reading }

photo { Pieter Hugo, Escort Kama, Enugu, Nigeria from Nollywood, 2008 }

ideas | January 20th, 2021 2:55 pm

Fette Sans: I want to cut you open and pour out all your insides, chew on your liver and your heart, and then sew you back together using your intestine and maybe I will pack you better than you were and there will be some left to crochet myself a necklace.

{ Forty-one reflections on 2020 | Continue reading }

ideas | December 25th, 2020 3:55 pm

Here’s a puzzle […] It’s called “Cain’s Jawbone,” in which people are challenged to put the shuffled pages of a murder mystery novel in their proper order. Since its creation in 1934, it has only been solved by two people — until now.

British comedian John Finnemore made it his quarantine project to crack “Cain’s Jawbone” — and he succeeded, making him just the third person to solve it in its nearly 90-year history. […]

The puzzle takes the form of 100 cards, each containing the page of a murder mystery novel. In order to solve the puzzle, participants must put all the cards in the proper order and determine who murders who in the story. There are 32 million possible combinations, which makes finding the correct result quite a feat.

{ The World | Continue reading }

books, leisure | December 3rd, 2020 5:49 pm

An astrophysicist of the University of Bologna and a neurosurgeon of the University of Verona compared the network of neuronal cells in the human brain with the cosmic network of galaxies, and surprising similarities emerged. […]

The human brain functions thanks to its wide neuronal network that is deemed to contain approximately 69 billion neurons. On the other hand, the observable universe can count upon a cosmic web of at least 100 billion galaxies. Within both systems, only 30% of their masses are composed of galaxies and neurons. Within both systems, galaxies and neurons arrange themselves in long filaments or nodes between the filaments. Finally, within both system, 70% of the distribution of mass or energy is composed of components playing an apparently passive role: water in the brain and dark energy in the observable Universe. […]

Probably, the connectivity within the two networks evolves following similar physical principles, despite the striking and obvious difference between the physical powers regulating galaxies and neurons”

{ Università di Bologna | Continue reading }

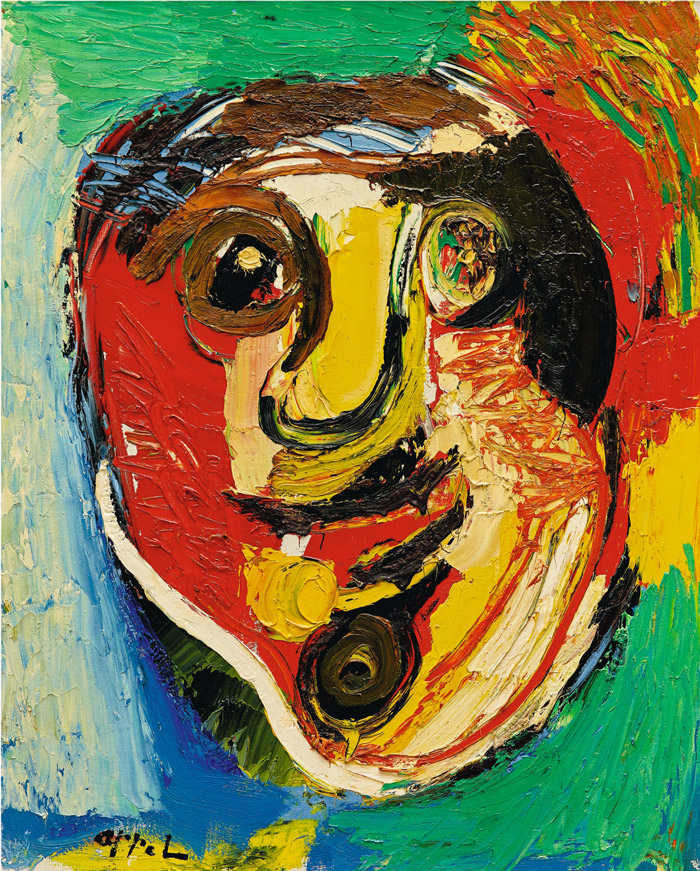

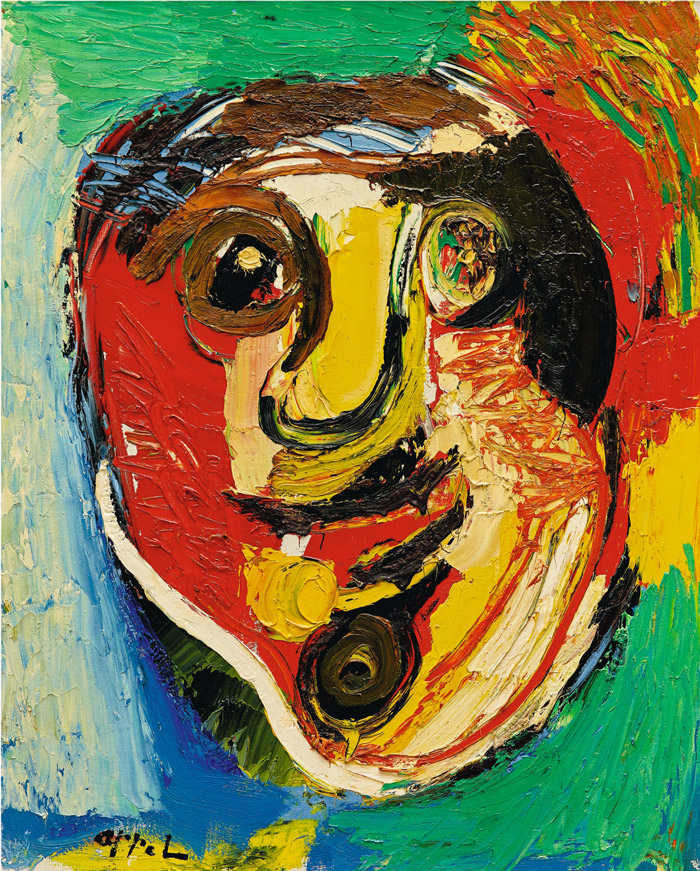

oil on canvas { Karel Appel, Portrait, 1966 }

brain, ideas, space | November 23rd, 2020 7:00 am

life expectancy for men in 1907 was 45.6 years; by 1957 it rose to 66.4; in 2007 it reached 75.5. Unlike the most recent increase in life expectancy (which was attributable largely to a decline in half of the leading causes of death including heart disease, homicide, and influenza), the increase in life expectancy between 1907 and 2007 was largely due to a decreasing infant mortality rate, which was 9.99 percent in 1907; 2.63 percent in 1957; and 0.68 percent in 2007.

But the inclusion of infant mortality rates in calculating life expectancy creates the mistaken impression that earlier generations died at a young age; Americans were not dying en masse at the age of 46 in 1907. The fact is that the maximum human lifespan — a concept often confused with “life expectancy” — has remained more or less the same for thousands of years. The idea that our ancestors routinely died young (say, at age 40) has no basis in scientific fact. […]

If a couple has two children and one of them dies in childbirth while the other lives to be 90, stating that on average the couple’s children lived to be 45 is statistically accurate but meaningless.

{ LiveScience | Continue reading | BBC }

flashback, health, time | September 27th, 2020 4:11 pm

Say you travelled in time, in an attempt to stop COVID-19’s patient zero from being exposed to the virus. However if you stopped that individual from becoming infected, that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place. This is a paradox, an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe. […] In the coronavirus patient zero example, you might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would. No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you. Try as you might to create a paradox, the events will always adjust themselves, to avoid any inconsistency.

{ Popular Mechanics | Continue reading | More: Classical and Quantum Gravity }

theory, time | September 27th, 2020 10:40 am

I examine the relationship between unhappiness and age using data from eight well-being data files on nearly 14 million respondents across forty European countries and the United States and 168 countries from the Gallup World Poll. […] Unhappiness is hill-shaped in age and the average age where the maximum occurs is 49 with or without controls.

{ Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization | Continue reading }

A large empirical literature has debated the existence of a U-shaped happiness-age curve. This paper re-examines the relationship between various measures of well-being and age in 145 countries. […] The U-shape of the curve is forcefully confirmed, with an age minimum, or nadir, in midlife around age 50 in separate analyses for developing and advanced countries as well as for the continent of Africa. The happiness curve seems to be everywhere.

{ Journal of Population Economics | PDF }

photo { Joseph Szabo }

eudaemonism | September 12th, 2020 10:41 am

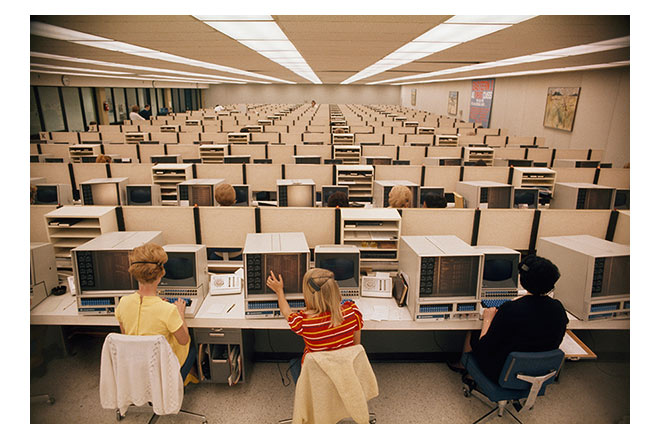

In the year 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that, by century’s end, technology would have advanced sufficiently that countries like Great Britain or the United States would have achieved a 15-hour work week. There’s every reason to believe he was right. In technological terms, we are quite capable of this. And yet it didn’t happen. Instead, technology has been marshaled, if anything, to figure out ways to make us all work more. In order to achieve this, jobs have had to be created that are, effectively, pointless. […]

productive jobs have, just as predicted, been largely automated away […] But rather than allowing a massive reduction of working hours to free the world’s population to pursue their own projects, pleasures, visions, and ideas […] It’s as if someone were out there making up pointless jobs just for the sake of keeping us all working. And here, precisely, lies the mystery. In capitalism, this is precisely what is not supposed to happen. Sure, in the old inefficient socialist states like the Soviet Union, where employment was considered both a right and a sacred duty, the system made up as many jobs as they had to (this is why in Soviet department stores it took three clerks to sell a piece of meat). But, of course, this is the sort of very problem market competition is supposed to fix. According to economic theory, at least, the last thing a profit-seeking firm is going to do is shell out money to workers they don’t really need to employ. Still, somehow, it happens.

{ David Graeber | Continue reading }

what I am calling “bullshit jobs” are jobs that are primarily or entirely made up of tasks that the person doing that job considers to be pointless, unnecessary, or even pernicious. Jobs that, were they to disappear, would make no difference whatsoever. Above all, these are jobs that the holders themselves feel should not exist.

Contemporary capitalism seems riddled with such jobs.

{ The Anarchist Library | Continue reading }

image { Alliander, ElaadNL, and The incredible Machine, Transparent Charging Station, 2017 }

economics, ideas | September 3rd, 2020 11:51 am

Moringa oleifera, an edible tree found worldwide in the dry tropics, is increasingly being used for nutritional supplementation. Its nutrient-dense leaves are high in protein quality, leading to its widespread use by doctors, healers, nutritionists and community leaders, to treat under-nutrition and a variety of illnesses. Despite the fact that no rigorous clinical trial has tested its efficacy for treating under-nutrition, the adoption of M. oleifera continues to increase. The “Diffusion of innovations theory” describes well the evidence for growth and adoption of dietary M. oleifera leaves, and it highlights the need for a scientific consensus on the nutritional benefits. […]

The regions most burdened by under-nutrition, (in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean) all share the ability to grow and utilize an edible plant, Moringa oleifera, commonly referred to as “The Miracle Tree.” For hundreds of years, traditional healers have prescribed different parts of M. oleifera for treatment of skin diseases, respiratory illnesses, ear and dental infections, hypertension, diabetes, cancer treatment, water purification, and have promoted its use as a nutrient dense food source. The leaves of M. oleifera have been reported to be a valuable source of both macro- and micronutrients and is now found growing within tropical and subtropical regions worldwide, congruent with the geographies where its nutritional benefits are most needed.

Anecdotal evidence of benefits from M. oleifera has fueled a recent increase in adoption of and attention to its many healing benefits, specifically the high nutrient composition of the plants leaves and seeds. Trees for Life, an NGO based in the United States has promoted the nutritional benefits of Moringa around the world, and their nutritional comparison has been widely copied and is now taken on faith by many: “Gram for gram fresh leaves of M. oleifera have 4 times the vitamin A of carrots, 7 times the vitamin C of oranges, 4 times the calcium of milk, 3 times the potassium of bananas, ¾ the iron of spinach, and 2 times the protein of yogurt” (Trees for Life, 2005).

Feeding animals M. oleifera leaves results in both weight gain and improved nutritional status. However, scientifically robust trials testing its efficacy for undernourished human beings have not yet been reported. If the wealth of anecdotal evidence (not cited herein) can be supported by robust clinical evidence, countries with a high prevalence of under-nutrition might have at their fingertips, a sustainable solution to some of their nutritional challenges. […]

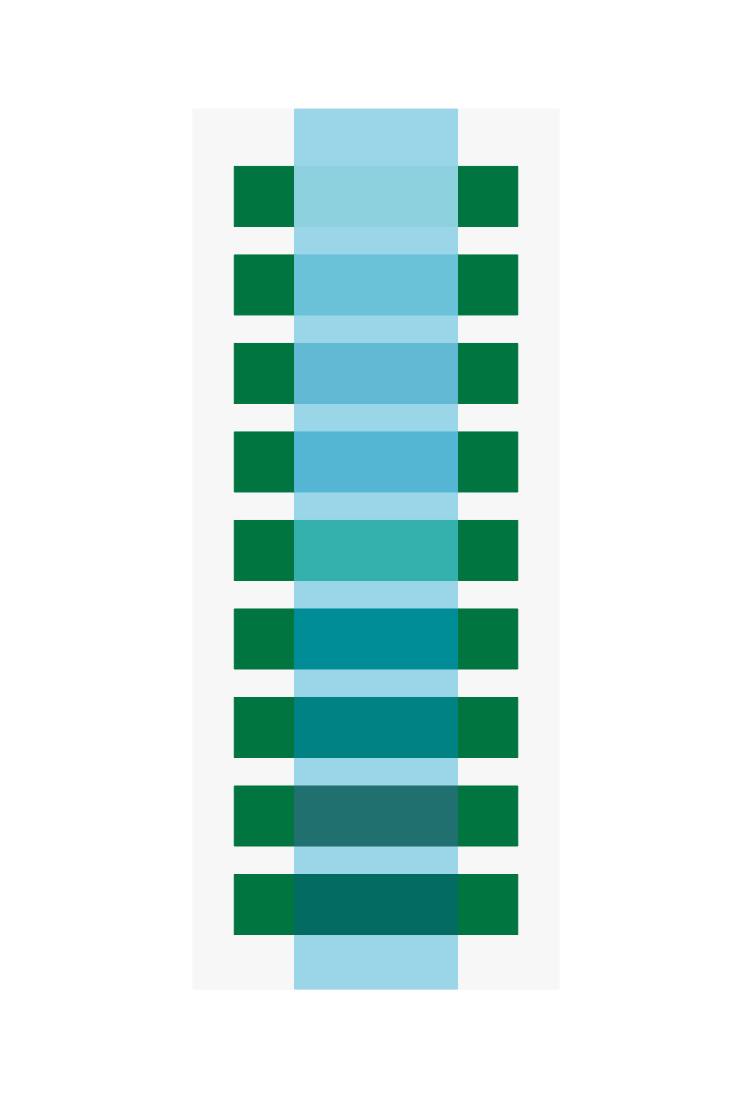

The “Diffusion of Innovations” theory explains the recent increase in M. oleifera adoption by various international organizations and certain constituencies within undernourished populations, in the same manner as it has been so useful in explaining the adoption of many of the innovative agricultural practices in the 1940-1960s. […] A sigmoidal curve (Figure 1), illustrates the adoption process starting with innovators (traditional healers in the case of M. oleifera), who communicate and influence early adopters, (international organizations), who then broadcast over time new information on M. oleifera adoption, in the wake of which adoption rate steadily increases.

{ Ecology of Food and Nutrition | Continue reading }

Dendrology, economics, food, drinks, restaurants, theory | September 1st, 2020 4:54 pm

Currently, we produce ∼1021 digital bits of information annually on Earth. Assuming a 20% annual growth rate, we estimate that after ∼350 years from now, the number of bits produced will exceed the number of all atoms on Earth, ∼1050. After ∼300 years, the power required to sustain this digital production will exceed 18.5 × 1015 W, i.e., the total planetary power consumption today, and after ∼500 years from now, the digital content will account for more than half Earth’s mass, according to the mass-energy–information equivalence principle. Besides the existing global challenges such as climate, environment, population, food, health, energy, and security, our estimates point to another singular event for our planet, called information catastrophe.

{ AIP Advances | Continue reading }

It is estimated that a week’s worth of the New York Times contains more information than a person was likely to come across in a lifetime in the 18th century. […] The amount of new information is doubling every two years. By 2010, it’s predicted to double every 72 hours. […] The lunatic named Bobby Fisher “despised the media”: “They’re destroying reality, turning everything into media.” “News exceed reality” writes Thomas Bernhard somewhere. The saturation and repetitions in Basquiat’s paintings. The high-frequency trading. “an immense accumulation of nothing“ (Imp Kerr, 2009). An immense accumulation of ignorance. […,]

From what precedes it necessarily follows that the inescapable future of knowledge is banality, falsehood, and overabundance, which sum is a form of ignorance.

{ The New Inquiry | Continue reading }

eschatology, ideas, media | August 20th, 2020 5:48 am

Enjoying short-term pleasurable activities that don’t lead to long-term goals contributes at least as much to a happy life as self-control, according to new research. […]

simply sitting about more on the sofa, eating more good food and going to the pub with friends more often won’t automatically make for more happiness.

{ UZH | Continue reading }

eudaemonism | August 2nd, 2020 6:08 am

The Parrondo’s paradox, has been described as: A combination of losing strategies becomes a winning strategy. […]

Consider two games Game A and Game B, this time with the following rules:

1. In Game A, you simply lose $1 every time you play.

2. In Game B, you count how much money you have left. If it is an even number, you win $3. Otherwise you lose $5.

Say you begin with $100 in your pocket. If you start playing Game A exclusively, you will obviously lose all your money in 100 rounds. Similarly, if you decide to play Game B exclusively, you will also lose all your money in 100 rounds.

However, consider playing the games alternatively, starting with Game B, followed by A, then by B, and so on (BABABA…). It should be easy to see that you will steadily earn a total of $2 for every two games.

Thus, even though each game is a losing proposition if played alone, because the results of Game B are affected by Game A, the sequence in which the games are played can affect how often Game B earns you money, and subsequently the result is different from the case where either game is played by itself.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

ideas | July 19th, 2020 5:53 pm

What is the feasibility of survival on another planet and being self-sustaining? […] I show here that a mathematical model can be used to determine the minimum number of settlers and the way of life for survival on another planet, using Mars as the example. […] The minimum number of settlers has been calculated and the result is 110 individuals.

{ Nature | Continue reading }

eschatology, theory | June 25th, 2020 7:55 am

eudaemonism, kids | April 13th, 2020 9:37 am

David Silver [the creator of AlphaZero] hasn’t answered my question about whether machines can set up their own goals. He talks about subgoals, but that’s not the same. That’s a certain gap in his definition of intelligence. We set up goals and look for ways to achieve them. A machine can only do the second part.

So far, we see very little evidence that machines can actually operate outside of these terms, which is clearly a sign of human intelligence. Let’s say you accumulated knowledge in one game. Can it transfer this knowledge to another game, which might be similar but not the same? Humans can. With computers, in most cases you have to start from scratch.

{ Gary Kasparov/Wired | Continue reading }

photo { Kelsey Bennett }

chess, ideas, psychology | February 23rd, 2020 8:28 pm

The madman theory is a political theory commonly associated with U.S. President Richard Nixon’s foreign policy. He and his administration tried to make the leaders of hostile Communist Bloc nations think Nixon was irrational and volatile. According to the theory, those leaders would then avoid provoking the United States, fearing an unpredictable American response.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

The author finds that perceived madness is harmful to general deterrence and is sometimes also harmful in crisis bargaining, but may be helpful in crisis bargaining under certain conditions.

{ British Journal of Political Science | Continue reading }

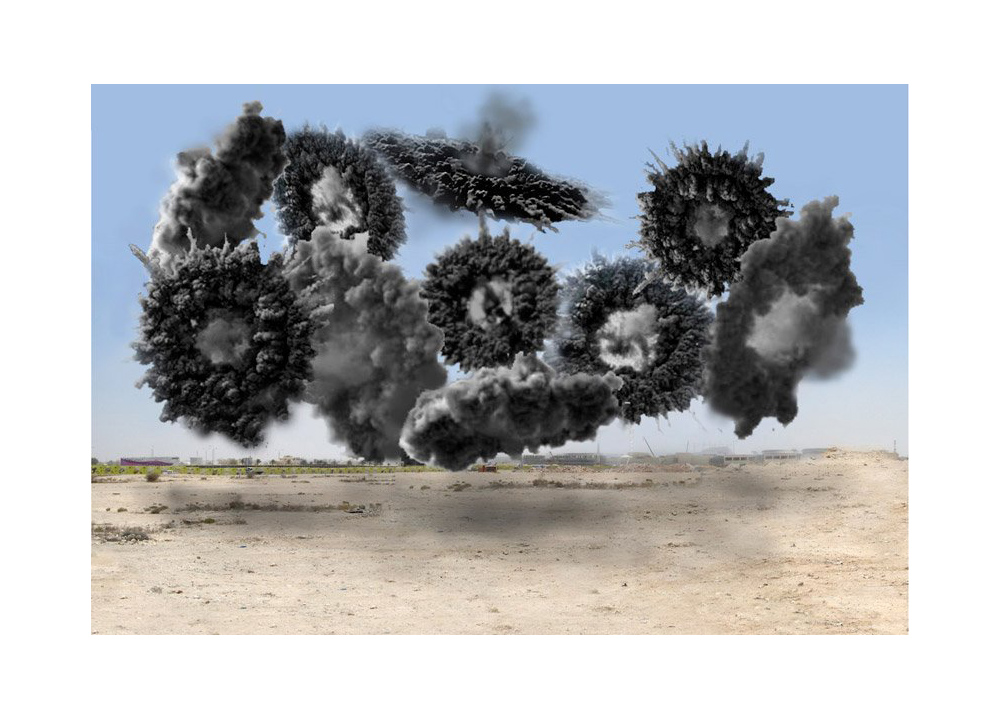

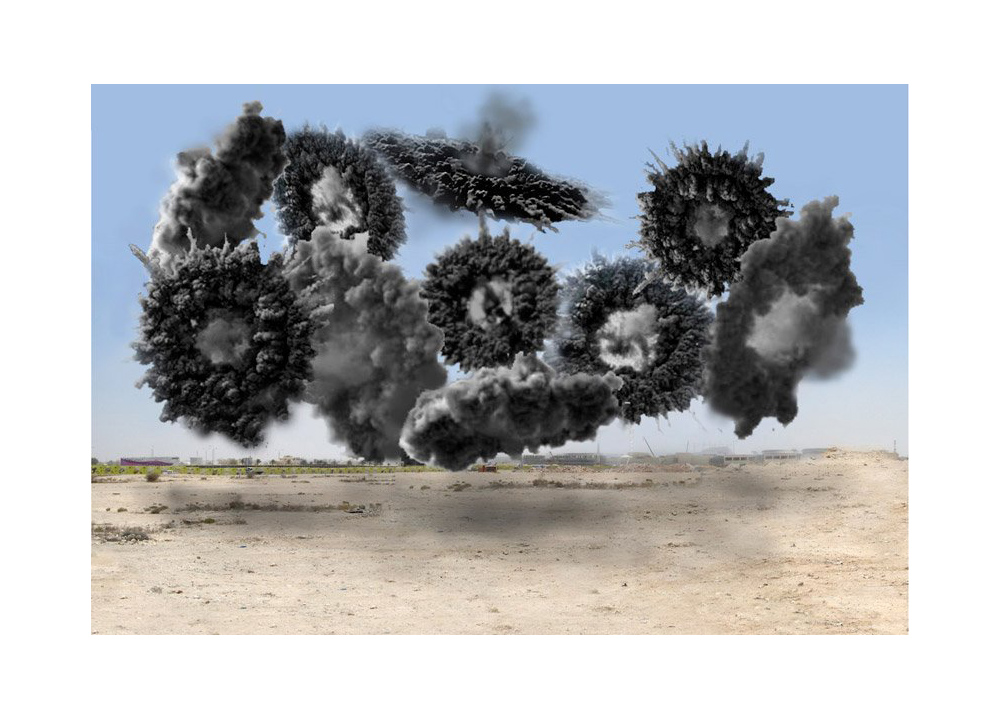

black smoke shells fitted with computer chips { Cai Guo-Qiang, Wreath (Black Ceremony), 2011 }

U.S., fights, theory | February 18th, 2020 4:47 pm

Founded in 1945 by University of Chicago scientists who had helped develop the first atomic weapons in the Manhattan Project, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists created the Doomsday Clock two years later, using the imagery of apocalypse (midnight) and the contemporary idiom of nuclear explosion (countdown to zero) to convey threats to humanity and the planet. The decision to move (or to leave in place) the minute hand of the Doomsday Clock is made every year by the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board in consultation with its Board of Sponsors, which includes 13 Nobel laureates. The Clock has become a universally recognized indicator of the world’s vulnerability to catastrophe from nuclear weapons, climate change, and disruptive technologies in other domains.

To: Leaders and citizens of the world

Re: Closer than ever: It is 100 seconds to midnight

Date: January 23, 2020

{ Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists | Continue reading }

eschatology | January 27th, 2020 9:19 pm

[W]hile time moves forward in our universe, it may run backwards in another, mirror universe that was created on the “other side” of the Big Bang.

{ PBS (2014) | Continue reading }

Physics, space, theory, time | January 23rd, 2020 6:54 pm

ideas, showbiz | January 22nd, 2020 4:55 pm

Using Music as Medicine – finding the optimum music listening ‘dosage’

There was a general agreement of dosage time across 3 of the 4 domains with 11 minutes being the most common amount of time it took for people to receive the therapeutic benefit from their self- selected music preferences. The only exception was the domain of happiness where the most common length of time for people to become happier after listening to their chosen music was reduced to 5 minutes, suggesting that happy music takes less time to take effect than other music.

{ British Academy of Sound Therapy.com | PDF | More

photo { Sarah Illenberger }

eudaemonism, music, psychology | January 12th, 2020 5:07 pm

Most of the research on happiness has documented that income, marriage, employment and health affect happiness. Very few studies examine whether happiness itself affect income, marriage, employment and health. […] Findings show that happier Indonesians in 2007 earned more money, were more likely to be married, were less likely to be divorced or unemployed, and were in better health when the survey was conducted again seven years later.

{ Applied Research in Quality of Life | Continue reading }

image { Maurizio Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari, Toilet Paper #1, June 2010 }

eudaemonism, psychology | November 30th, 2019 1:24 pm

English speakers have been deprived of a truly functional, second person plural pronoun since we let “ye” fade away a few hundred years ago.

“You” may address one person or a bunch, but it can be imprecise and unsatisfying. “You all”—as in “I’m talking to you all,” or “Hey, you all!”—sounds wordy and stilted. “You folks” or “you gang” both feel self-conscious. Several more economical micro-regional varieties (youz, yinz) exist, but they lack wide appeal.

But here’s what’s hard to explain: The first, a gender-neutral option, mainly thrives in the American South and hasn’t been able to steal much linguistic market share outside of its native habitat. The second, an undeniable reference to a group of men, is the default everywhere else, even when the “guys” in question are women, or when the speaker is communicating to a mixed gender group.

“You guys,” rolls off the tongues of avowed feminists every day, as if everyone has agreed to let one androcentric pronoun pass, while others (the generic “he” or “men” as stand-ins for all people) belong to the before-we-knew-better past. […]

One common defense of “you guys” that Mallinson encounters in the classroom and elsewhere is that it is gender neutral, simply because we use it that way. This argument also appeared in the New Yorker recently, in a column about a new book, The Life of Guy: Guy Fawkes, the Gunpowder Plot, and the Unlikely History of an Indispensable Word by writer and educator Allan Metcalf.

“Guy” grew out of the British practice of burning effigies of the Catholic rebel Guy Fawkes, Metcalf explains in the book. The flaming likenesses, first paraded in the early 1600s, came to be called “guys,” which evolved to mean a group of male lowlifes, he wrote in a recent story for Time. Then, by the 18th century, “guys” simply meant “men” without any pejorative connotations. By the 1930s, according to the Washington Post, Americans had made the leap to calling all persons “guys.”

{ Quartz | Continue reading }

Linguistics | November 29th, 2019 10:13 pm

kids, showbiz, time | November 14th, 2019 8:00 am

of course there is no behind the scenes, no real self, no authenticity, etc. just a precession of simulacra; influencers sort of serve the same function Baudrillard thought Disneyland served: to make everyone else feel “authentic”

{ Rob Horning }

ideas, social networks | September 16th, 2019 4:17 pm

[S]ome languages—such as Japanese, Basque, and Italian—are spoken more quickly than others. […]

Linguists have spent more time studying not just speech rate, but the effort a speaker has to exert to get a message across to a listener. By calculating how much information every syllable in a language conveys, it’s possible to compare the “efficiency” of different languages. And a study published today in Science Advances found that more efficient languages tend to be spoken more slowly. In other words, no matter how quickly speakers chatter, the rate of information they’re transmitting is roughly the same across languages.

The basic problem of “efficiency,” in linguistics, starts with the trade-off between effort and communication. It takes a certain amount of coordination, and burns a certain number of calories, to make noises come out of your mouth in an intelligible way. And those noises can be more or less informative to a listener, based on how predictable they are. If you and I are discussing dinosaurs, you wouldn’t be surprised to hear me rattle off the names of my favorite species. But if a stranger walks up to you on the street and announces, “Diplodocus!” it’s unexpected. It narrows the scope of possible conversation topics greatly and is therefore highly informative.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

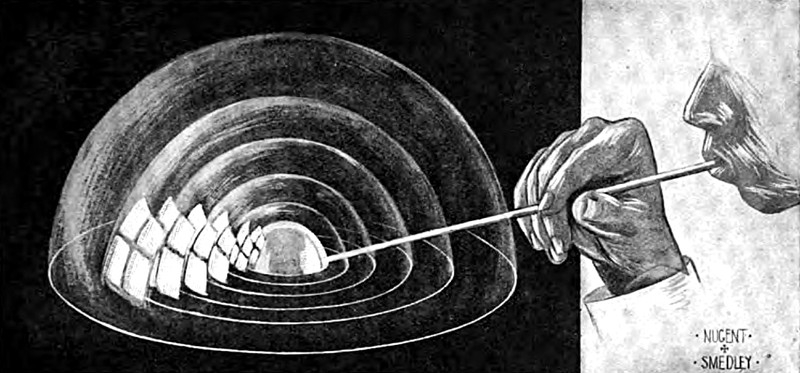

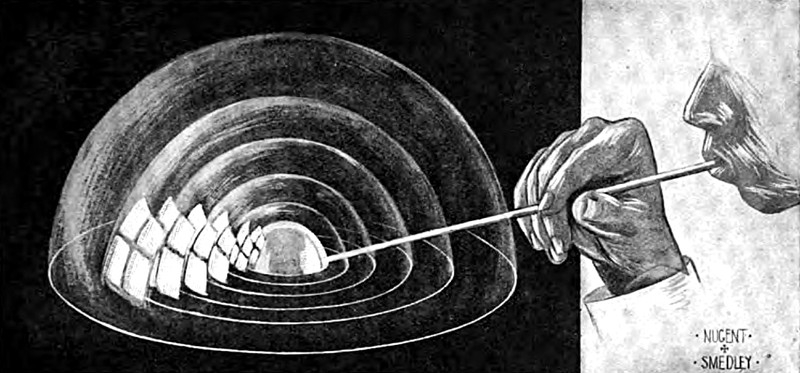

image { Six soap bubbles inside one another, from The Windsor Magazine, 1902 }

Linguistics | September 8th, 2019 8:51 am

Cooping was an alleged form of electoral fraud in the United States cited in relation to the death of Edgar Allan Poe in October 1849, by which unwilling participants were forced to vote, often several times over, for a particular candidate in an election. According to several of Poe’s biographers, these innocent bystanders would be grabbed off the street by so-called ‘cooping gangs’ or ‘election gangs’ working on the payroll of a political candidate, and they would be kept in a room, called the “coop”, and given alcoholic beverages in order for them to comply. If they refused to cooperate, they would be beaten or even killed. Often their clothing would be changed to allow them to vote multiple times. Sometimes the victims would be forced to wear disguises such as wigs, fake beards or mustaches to prevent them from being recognized by voting officials at polling stations.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

On October 3, 1849, Edgar Allan Poe was found delirious on the streets of Baltimore, “in great distress, and… in need of immediate assistance”, according to Joseph W. Walker who found him. He was taken to the Washington Medical College where he died on Sunday, October 7, 1849 at 5:00 in the morning. He was not coherent long enough to explain how he came to be in his dire condition and, oddly, was wearing clothes that were not his own.

He is said to have repeatedly called out the name “Reynolds” on the night before his death, though it is unclear to whom he was referring.

All medical records and documents, including Poe’s death certificate, have been lost, if they ever existed.

Newspapers at the time reported Poe’s death as “congestion of the brain” or “cerebral inflammation”, common euphemisms for death from disreputable causes such as alcoholism.

The actual cause of death remains a mystery. […] One theory dating from 1872 suggests that cooping was the cause of Poe’s death, a form of electoral fraud in which citizens were forced to vote for a particular candidate, sometimes leading to violence and even murder. […] Cooping had become the standard explanation for Poe’s death in most of his biographies for several decades, though his status in Baltimore may have made him too recognizable for this scam to have worked. […]

Immediately after Poe’s death, his literary rival Rufus Wilmot Griswold wrote a slanted high-profile obituary under a pseudonym, filled with falsehoods that cast him as a lunatic and a madman, and which described him as a person who “walked the streets, in madness or melancholy, with lips moving in indistinct curses, or with eyes upturned in passionate prayers, (never for himself, for he felt, or professed to feel, that he was already damned)”.

The long obituary appeared in the New York Tribune signed “Ludwig” on the day that Poe was buried. It was soon further published throughout the country. The piece began, “Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it.” “Ludwig” was soon identified as Griswold, an editor, critic, and anthologist who had borne a grudge against Poe since 1842. Griswold somehow became Poe’s literary executor and attempted to destroy his enemy’s reputation after his death.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

books, flashback, mystery and paranormal, scams and heists | August 25th, 2019 2:46 pm

“The maximum speed required to break through the earth’s gravitational pull is seven miles a second,” says David Wojnarowicz. “Since economic conditions prevent us from gaining access to rockets or spaceships, we would have to learn to run awful fast to achieve escape from where we all are heading.”

{ The New Inquiry | Continue reading }

ideas | July 17th, 2019 6:49 am

In mid-1947, a United States Army Air Forces balloon crashed at a ranch near Roswell, New Mexico. Following wide initial interest in the crashed “flying disc”, the US military stated that it was merely a conventional weather balloon. Interest subsequently waned until the late 1970s, when ufologists began promoting a variety of increasingly elaborate conspiracy theories, claiming that one or more alien spacecraft had crash-landed and that the extraterrestrial occupants had been recovered by the military, which then engaged in a cover-up.

In the 1990s, the US military published two reports disclosing the true nature of the crashed object: a nuclear test surveillance balloon from Project Mogul.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

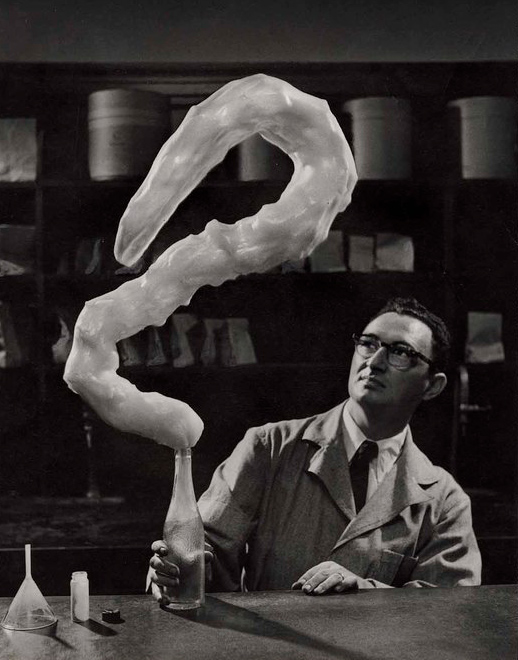

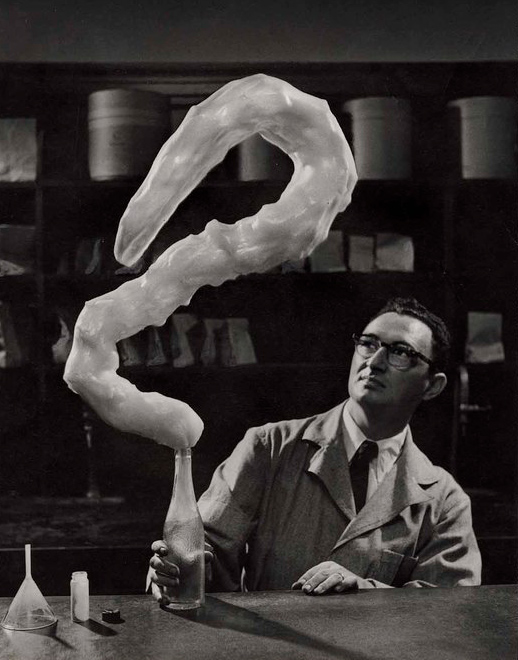

photo { W. Eugene Smith, Untitled [man holding bottle, S-shaped foam form emerging from it], Springfield, Massachusetts, 1952 }

U.S., controversy, flashback | July 11th, 2019 8:07 am

Suppose you live in a deeply divided society: 60% of people strongly identify with Group A, and the other 40% strongly identify with Group B. While you plainly belong to Group A, you’re convinced this division is bad: It would be much better if everyone felt like they belonged to Group AB. You seek a cohesive society, where everyone feels like they’re on the same team.

What’s the best way to bring this cohesion about? Your all-too-human impulse is to loudly preach the value of cohesion. But on reflection, this is probably counter-productive. When members of Group B hear you, they’re going to take “cohesion” as a euphemism for “abandon your identity, and submit to the dominance of Group A. ”None too enticing. And when members of Group A notice Group B’s recalcitrance, they’re probably going to think, “We offer Group B the olive branch of cohesion, and they spit in our faces. Typical.” Instead of forging As and Bs into one people, preaching cohesion tears them further apart.

What’s the alternative? Simple. Instead of preaching cohesion, reach out to Group B. Unilaterally show them respect.Unilaterally show them friendliness. They’ll be distrustful at first, but cohesion can’t be built in a day.

{ The Library of Economics and Liberty | Continue reading }

photo { Stephen Shore, Queens, New York, April 1972 }

ideas, photogs, psychology, relationships | June 16th, 2019 2:01 pm

The mind-body problem enjoyed a major rebranding over the last two decades and is generally known now as the “hard problem” of consciousness […] Fast forward to the present era and we can ask ourselves now: Did the hippies actually solve this problem? My colleague Jonathan Schooler of the University of California, Santa Barbara, and I think they effectively did, with the radical intuition that it’s all about vibrations … man. Over the past decade, we have developed a “resonance theory of consciousness” that suggests that resonance—another word for synchronized vibrations—is at the heart of not only human consciousness but of physical reality more generally. […]

Stephen Strogatz provides various examples from physics, biology, chemistry and neuroscience to illustrate what he calls “sync” (synchrony) […] Fireflies of certain species start flashing their little fires in sync in large gatherings of fireflies, in ways that can be difficult to explain under traditional approaches. […] The moon’s rotation is exactly synced with its orbit around the Earth such that we always see the same face. […]

The panpsychist argues that consciousness (subjectivity) did not emerge; rather, it’s always associated with matter, and vice versa (they are two sides of the same coin), but mind as associated with most of the matter in our universe is generally very simple. An electron or an atom, for example, enjoy just a tiny amount of consciousness. But as matter “complexifies,” so mind complexifies, and vice versa.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading | Thanks Tim }

brain, ideas, neurosciences | June 13th, 2019 2:03 pm

Despite variation in lifestyle and environment, first signs of human facial aging show between the ages of 20–30 years. It is a cumulative process of changes in the skin, soft tissue, and skeleton of the face. As quantifications of facial aging in living humans are still scarce, we set out to study age-related changes in three- dimensional facial shape using geometric morphometrics.

We collected surface scans of 88 human faces (aged 26–90 years) from the coastal town Split (Croatia) and neighboring islands. Based on a geometric morphometric analysis of 585 measurement points (landmarks and semi- landmarks), we modeled sex-specific trajectories of average facial aging.

Age-related facial shape change was similar in both sexes until around age 50, at which time the female aging trajectory turned sharply. The overall magnitude of facial shape change (aging rate) was higher in women than men, especially in early postmenopause. Aging was generally associated with a flatter face, sagged soft tissue (“broken” jawline), deeper nasolabial folds, smaller visible areas of the eyes, thinner lips, and longer nose and ears. In postmenopausal women, facial aging was best predicted by the years since last menstruation and mainly attributable to bone resorption in the mandible.

{ Physical Anthropology | Continue reading }

faces, science, time | June 13th, 2019 1:46 pm

Can events be accurately described as historic at the time they are happening?

Claims of this sort are in effect predictions about the evaluations of future historians; that is, that they will regard the events in question as significant.

Here we provide empirical evidence in support of earlier philosophical arguments1 that such claims are likely to be spurious and that, conversely, many events that will one day be viewed as historic attract little attention at the time.

{ Nature Human Behaviour | Continue reading }

photo { David Sims }

ideas, photogs | June 13th, 2019 12:33 pm

Picture some serious non-fiction tomes. The Selfish Gene; Thinking, Fast and Slow; Guns, Germs, and Steel; etc. Have you ever had a book like this—one you’d read—come up in conversation, only to discover that you’d absorbed what amounts to a few sentences? I’ll be honest: it happens to me regularly. Often things go well at first. I’ll feel I can sketch the basic claims, paint the surface; but when someone asks a basic probing question, the edifice instantly collapses. Sometimes it’s a memory issue: I simply can’t recall the relevant details. But just as often, as I grasp about, I’ll realize I had never really understood the idea in question, though I’d certainly thought I understood when I read the book. Indeed, I’ll realize that I had barely noticed how little I’d absorbed until that very moment.

{ Andy Matuschak | Continue reading }

books, experience | May 13th, 2019 10:19 am

Throughout her life, Bly—born Elizabeth Jane Cochran 155 years ago on May 5, 1864—refused to be what other people wanted her to be. That trait, some philosophers say, is the key to human happiness, and Bly’s life shows why.

{ Quartz | Continue reading }

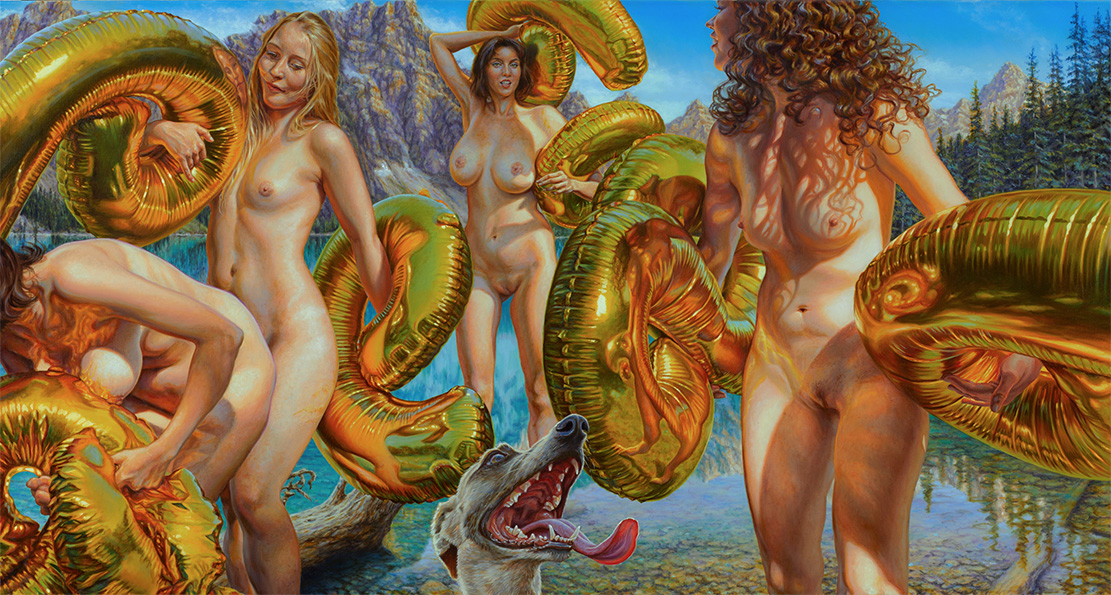

oil on linen { Susannah Martin, Helium, 2017 }

eudaemonism, flashback | May 6th, 2019 8:01 am

S is a woman if and only if:

S is systematically subordinated along some dimension (economic, legal, political, social, etc) and S is ‘marked’ as a target for this treatment by observed or imagined bodily features presumed to be evidence of a female’s biological role in reproduction.

To be a woman is to be subordinated in some way because of real or imagined biological features that are meant to indicate one’s female role in reproduction.

{ Aeon | Continue reading }

ideas, relationships | May 1st, 2019 3:15 pm

According to the 2019 World Happiness Report, negative feelings are rising around the world—and the United States is particularly hard hit with an “epidemic of addictions.” Tellingly, the report also shows a widening happiness gap, with some people reporting much more well-being and others showing much less within each country. […]

Negative feelings—worry, sadness, and anger—have been rising around the world, up by 27 percent from 2010 to 2018. […]

“The U.S. is suffering an epidemic of addictions.” This includes an addiction to technology, which researcher Jean Twenge largely blames for the worrying mental health trends among U.S. adolescents. In her chapter of the report, she argues that screen time is displacing activities that are key to our happiness, like in-person social contact. Forty-five percent of adolescents are online “almost constantly,” and the average high school senior spends six hours a day texting, on social media or on the internet.

But we’re hooked on more than just technology. According to researcher Steve Sussman, around half of Americans suffer from at least one addiction. Some of the most prevalent are alcohol, food, and work—which each affect around 10 percent of adults—as well as drugs, gambling, exercise, shopping, and sex.

There’s another possible explanation for unhappiness, though: Governments are losing their way. […] According to survey results since 2005, people across the globe are more satisfied with life when their governments are more effective, enforce the rule of law, have better regulation, control corruption, and spend in certain ways—more on health care and less on military.

{ Yes | Continue reading }

eudaemonism, psychology | May 1st, 2019 10:54 am

Where Does Time Go When You Blink?

Retinal input is frequently lost because of eye blinks, yet humans rarely notice these gaps in visual input. […]

Here, we investigated whether the subjective sense of time is altered by spontaneous blinks. […]

The results point to a link between spontaneous blinks, previously demonstrated to induce activity suppression in the visual cortex, and a compression of subjective time.

{ bioRxiv | Continue reading }

photo { Helmut Newton, A cure for a black eye, Jerry Hall, 1974 }

eyes, time | April 18th, 2019 12:50 pm

Based on the analysis of 190 studies (17,887 participants), we estimate that the average silent reading rate for adults in English is 238 word per minute (wpm) for non-fiction and 260 wpm for fiction. The difference can be predicted by the length of the words, with longer words in non-fiction than in fiction. The estimates are lower than the numbers often cited in scientific and popular writings. […] The average oral reading rate (based on 77 studies and 5,965 participants) is 183 wpm.

{ PsyArXiv | Continue reading }

Linguistics | April 13th, 2019 10:26 am

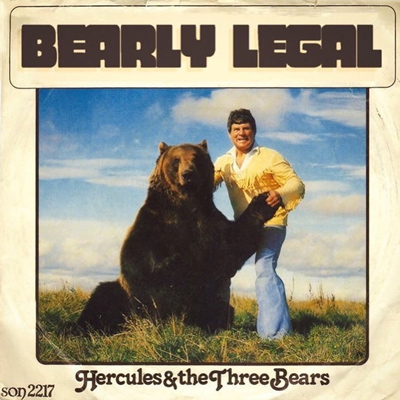

The Twelve Labours of Heracles are a series of episodes concerning a penance carried out by Heracles or Hercules, the greatest of the Greek heroes, whose name was later romanised as Hercules. They were accomplished over 12 years at the service of King Eurystheus.

[…]

Driven mad by Hera (queen of the gods), Hercules slew his son, daughter, and wife Megara. After recovering his sanity, Hercules deeply regretted his actions; he was purified by King Thespius, then traveled to Delphi to inquire how he could atone for his actions. Pythia, the Oracle of Delphi, advised him to go to Tiryns and serve his cousin King Eurystheus for twelve years, performing whatever labors Eurystheus might set him; in return, he would be rewarded with immortality.

[…]

Eurystheus originally ordered Hercules to perform ten labours. Hercules accomplished these tasks, but Eurystheus refused to recognize two: the slaying of the Lernaean Hydra, as Hercules’ nephew and charioteer Iolaus had helped him; and the cleansing of the Augeas, because Hercules accepted payment for the labour. Eurystheus set two more tasks (fetching the Golden Apples of Hesperides and capturing Cerberus), which Hercules also performed, bringing the total number of tasks to twelve.

[…]

The twelve labours:

1. Slay the Nemean lion.

2. Slay the nine-headed Lernaean Hydra.

3. Capture the Ceryneian Hind.

4. Capture the Erymanthian Boar.

5. Clean the Augean stables in a single day.

6. Slay the Stymphalian birds.

7. Capture the Cretan Bull.

8. Steal the Mares of Diomedes.

9. Obtain the girdle of Hippolyta.

10. Obtain the cattle of the monster Geryon.

11. Steal the apples of the Hesperides.

12. Capture and bring back Cerberus.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

helmet, acrylic and crayon { Jean-Michel Basquiat, AARON, 1981 }

allegories, flashback | April 13th, 2019 10:20 am