Try everything twice. The first time you might have been doing it wrong.

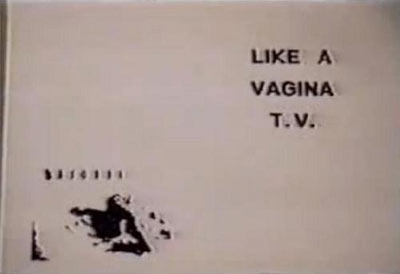

“Rocket Queen” is the closing song of American hard rock band Guns N’ Roses’ debut studio album Appetite for Destruction. […]

Axl wanted some pornographic sounds on Rocket Queen, so he brought a girl in and they had sex in the studio. We wound up recording about 30 minutes of sex noises. If you listen to the break on Rocket Queen it’s in there.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading | Thanks Tim! }

Not to mention another membrane

One definition is that a Type III error occurs when you get the right answer to the wrong question. This is sometimes called a Type 0 error.

photos { Stephen Shore, American Surfaces, 1972 }

The beautiful ineffectual dreamer who comes to grief against hard facts

There’s another problem with using common sense. The real world is very complex, and no one model can explain everything.

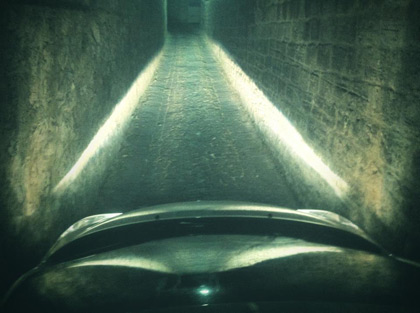

photo { Joel Meyerowitz }

‘The human mind cannot be absolutely destroyed with the body, but there remains of it something which is eternal.’ –Spinoza

Hayworth has spent much of the past few years in a windowless room carving brains into very thin slices. He is by all accounts a curious man, known for casually saying things like, “The human race is on a beeline to mind uploading: We will preserve a brain, slice it up, simulate it on a computer, and hook it up to a robot body.” He wants that brain to be his brain. He wants his 100 billion neurons and more than 100 trillion synapses to be encased in a block of transparent, amber-colored resin—before he dies of natural causes.

Why? Ken Hayworth believes that he can live forever. […]

By 2110, Hayworth predicts, mind uploading—the transfer of a biological brain to a silicon-based operating system—will be as common as laser eye surgery is today. […]

To understand why Hayworth wants to plastinate his own brain you have to understand his field—connectomics, a new branch of neuroscience. A connectome is a complete map of a brain’s neural circuitry. Some scientists believe that human connectomes will one day explain consciousness, memory, emotion, even diseases like autism, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer’s—the cures for which might be akin to repairing a wiring error.

photo { Matthias Heiderich }

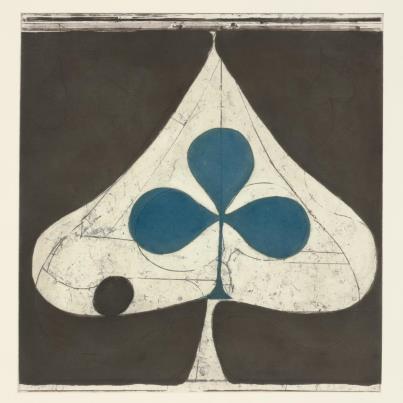

Let’s just call a spade a spade

Excavations at Cladh Hallan, a Bronze Age-Iron Age settlement on South Uist in the Outer Hebrides off the west coast of Scotland, revealed the skeletons of two adults, a sub-adult and a child buried beneath the foundations of three roundhouses. Osteological and isotopic evidence has shown that the male adult skeleton is a composite made up of parts of at least three different individuals. To test the hypothesis that the female skeleton was also a composite we examined ancient DNA from four of its components: the skull, mandible, right humerus and right femur. […]

It was concluded that the mandible, humerus and femur come from different individuals. Insufficient data were obtained to draw conclusions regarding the origin of the skull.

The presence of two composite skeletons at Cladh Hallan indicates that the merging of identities may have been a deliberate act, perhaps designed to amalgamate different ancestries into a single lineage.

{ ScienceDirect | Continue reading }

Mummies found off the coast of Scotland are Frankenstein-like composites of several corpses, researchers say. […]

Carbon dating these remains and their surroundings revealed these bodies were buried up to 600 years after death — to keep bodies from rotting to pieces after such a long time, they must have been intentionally preserved, unlike the bodies of animals also buried at the site, which had been left to decay. […]

The first composite was apparently assembled between 1260 B.C. and 1440 B.C., while the second composite was assembled between 1130 B.C. and 1310 B.C. “There is overlap, but the statistical probability is that they were assembled at different times,” Parker-Pearson said.

photo { Ron Jude }

Between what I’ve been trying so hard to see, and what appears to be real

Far from processing every word we read or hear, our brains often do not even notice key words that can change the whole meaning of a sentence, according to new research. […]

Semantic illusions provide a strong line of evidence that the way we process language is often shallow and incomplete. […]

Analyses of brain activity revealed that we are more likely to use this type of shallow processing under conditions of higher cognitive load — that is, when the task we are faced with is more difficult or when we are dealing with more than one task at a time.

The idea of nostalgia as a disruption of time

Memories merge into memories. Byatt’s grandmother’s vivid remembering becomes the granddaughter’s vivid imagining. Who can tell the difference? In time, we might become so convinced by other people’s descriptions of their memories that we start to claim them as our own. If the experimental conditions are set up correctly, it turns out to be rather simple to give people memories for events they never actually experienced.

A well-known series of experiments by the American cognitive psychologist Elizabeth Loftus and her colleagues at the University of Washington has shown that presenting participants with misleading information after they have experienced an event can change their memory of the event. […]

A recent neuroimaging study has provided some of the first clues to the neural mechanisms involved when our memories are shaped by other people. […] The scan findings showed that persistent memory errors, which went on to become part of the subjects’ own retelling of the story, were associated with greater activation in the hippocampus (the brain region primarily responsible for laying down episodic memories) than transient errors, which seemed to be more about conforming to a public account of the events. The researchers also showed that the amygdala (a part of the brain responsible for emotional memory) was particularly active when the participants thought that the information had come from other people, as compared with computer-generated representations. They suggested that the amygdala, so closely connected to the hippocampus, may play a specific role in the process by which social influences shape our memories. […]

A team of British researchers recently conducted the first scientific study of “nonbelieved memories”: memories which people cease to believe after coming to realise that they are false.

photo { Tim Geoghegan }

‘My doctor told me to stop having intimate dinners for four. Unless there are three other people.’ –Orson Welles

Whenever a pharmaceutical company tests a new migraine prevention drug, nearly 1 in 20 subjects will drop out because they can’t stand the drug’s side effects. They’d rather deal with the headaches than keep receiving treatment. But those suffering patients might be surprised to learn that the drug they’ve quit is only a sugar pill: the 5 percent dropout rate is from the placebo side.

Lurking in the shadows around any discussion of the placebo effect is its nefarious and lesser-known twin, the nocebo effect. Placebo is Latin for “I will please”; nocebo means “I will do harm.”

Che bella giornata! [wink]

The theory that liars look up to the right has been proved wrong

A paper published in PLOS ONE has apparently disproved the long-standing theory that direction of eye gaze can indicate lying. The theory which forms part of the bed-rock of the controversial offshoot of psychology called ‘Neuro-linguistic programming’ (NLP) has in fact never actually been experimentally researched until now. The study found absolutely no correlation between eye gaze and lying. Considering that this theory has become such a staple of popular psychology, it really is astounding that this was not discovered sooner.

photo { Ewen Spencer }

The delegation, present in full force, consisted of Commendatore Bacibaci Beninobenone (the semi-paralysed doyen of the party who had to be assisted to his seat by the aid of a powerful steam crane), the Archjoker Leopold Rudolph von Schwanzenbad-Hodenthaler, Countess Marha Virdga Kisászony Putrápesthi…

Fallout continues from the MOCA board’s removal of chief curator Paul Schimmel.

“Jeffrey has always been supportive of my work, but I don’t understand the direction he’s taking the museum right now,” McCarthy said. “I see it as placating the populace. It’s not really what art’s about, but a ratings game.”

Among those in Deitch’s corner is Shepard Fairey, an art star of a younger generation, especially since he designed the “Hope” poster that became the unofficial image of Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. (The design firm Fairey founded, Studio One, is now handling much of MOCA’s design work.)

In an email, Fairey, 42, praised Deitch’s “astute understanding of the interconnected nature of high and low art culture. When I say low, I don’t mean inferior.”

{ LA Times | Continue reading }

John Baldessari, citing Paul Schimmel’s ouster, becomes the fifth trustee to bolt since February.

threesome { Jeffrey Deitch, Yoko Ono, Jeff Koons }

Think she’s that way inclined a bit

Our own stomachs may be something of a dark mystery to most of us, but new research is revealing the surprising ways in which our guts exert control over our mood and appetite.

I recently watched live pictures from my own stomach as the porridge I had eaten for breakfast was churned, broken up, exposed to acid and then pushed out into my small intestine as a creamy mush called chyme.

I had swallowed a miniature camera in the form of a pill that would spend the day travelling through my digestive system, projecting images onto a giant screen.

Its first stop was my stomach, whose complex work is under the control of what’s sometimes called “the little brain”, a network of neurons that line your stomach and your gut.

Surprisingly, there are over 100 million of these cells in your gut, as many as there are in the head of a cat.

He drink me my teas. He eat me my sugars. Because he no pay me my moneys?

When we observe other people we attribute their behaviour to their character rather than to their situation – my wife’s carelessness means she loses her keys, your clumsiness means you trip over, his political opinions mean that he got into an argument. When we think about things that happen to us the opposite holds. We downplay our own dispositions and emphasise the role of the situation. Bad luck leads to lost keys, a hidden bump causes trips, or a late train results in an unsuccessful job interview – it’s never anything to do with us.

This pattern is so common that psychologists have called it the fundamental attribution error. […]

We blame individuals for what happens to them because of the general psychological drive to find causes for things. We have an inherent tendency to pick out each other as causes; even from infancy, we pay more attention to things that move under their own steam, that act as if they have a purpose. The mystery is not that people become the focus of our reasoning about causes, but how we manage to identify any single cause in a world of infinite possible causes.

Gave my hand a great squeeze going along by the Tolka in my hand

They walked to Ringsend, on the south bank of the Liffey, where (and here we can drop the Dante analogy) she put her hand inside his trousers and masturbated him. It was June 16, 1904, the day on which Joyce set “Ulysses.” When people celebrate Bloomsday, that is what they are celebrating. […]

Joyce had known only prostitutes and proper middle-class girls. Nora was something new, an ordinary woman who treated him as an ordinary man. The moral simplicity of what happened between them seems to have stunned him. It was elemental, a gratuitous act of loving that had not involved flattery or deceit, and that was unaccompanied by shame or guilt. That simplicity became the basis of their relationship.

related { Being in a relationship that others disapprove of }