Like a door that keeps revolving in a half forgotten dream

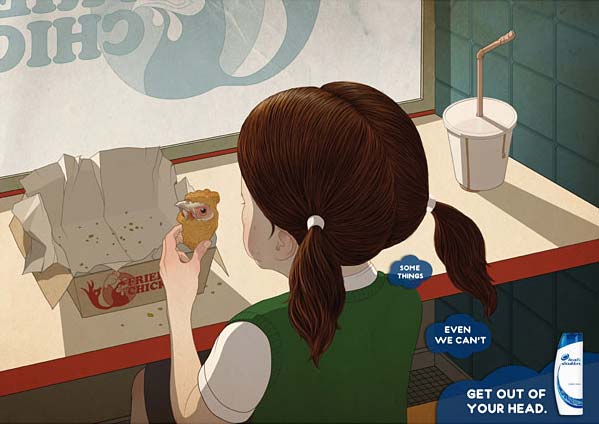

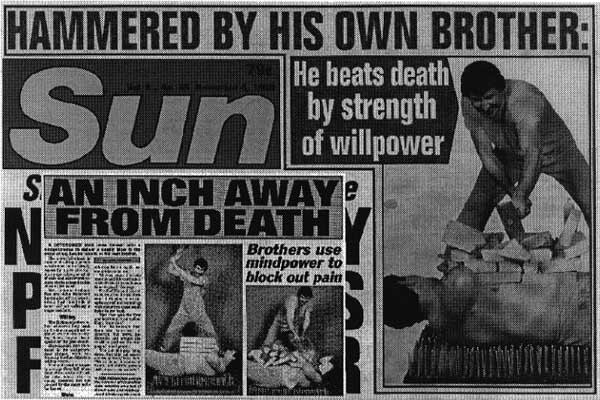

If someone tells you something that isn’t true, they may not be lying. At least not in the conventional sense. Confabulation, a rare disorder resulting from severe brain damage, causes its sufferers to relentlessly invent and believe fictions—both mundane and fantastical—about their lives. If asked where she has just been, a patient might say that she was in the laundry room (when she wasn’t) or that she’s been visiting Scotland with her sister (who’s been dead for 20 years), or even that she isn’t in the room where you’re talking to her, but in one exactly like it, further down the corridor. And could you fetch her hand cream please? These stories aren’t maintained for long periods, but are sincerely believed.

While it only affects a tiny minority of those with brain damage, confabulation tells us something important: that spontaneous, fluid, even riotous creativity is a natural part of the design of the mind. The damage associated with confabulation—usually to the frontal lobes—adds nothing to the brain’s makeup. Instead it releases a capacity for fiction that lies dormant inside all of us. Anyone who has seen children at play knows that the desire to make up stories is deeply embedded in human nature. And it can be cultivated too, most clearly by anarchic improvisers like Paul Merton.

{ Idiolect/Prospect magazine | Continue reading | via MindHacks }

photo { Jessica Craig-Martin }