MOMA’s founding director and “intellectual creator” viewed Johns’ first solo show at Leo Castelli and telephoned MOMA curator Dorothy Miller to come right over so they could select works. They purchased Johns’ 1954 Flag, Green Target, Target with Four Faces and White Numbers (thus anointing the 28-year-old into the modernist pantheon).

{ Art Net | Continue reading }

Rauschenberg opened up the possibilities that are now being mined by contemporary con-artists such as Damien Hirst, Mike Kelley, and Jeff Koons. Rauschenberg didn’t poeticize the ordinary. He aggrandized the ordinary, he put a high-art style price tag on the ordinary.

{ The New Republic | Continue reading }

$12 million, that’s how much Damien Hirst’s famous shark sold for in 2005. …. It’s not just about the work of art; rather, the value placed on a particular work derives from how it feels to own that art. Most art dealers know that art buying is all about what tier of buyers you aspire to join, about establishing a self-identity and, yes, getting some publicity. The network of galleries and auction houses spends a lot of its time, money, and energy giving artworks just the right image. Remarkably, buyers support the process in the interest of coming out on top, rather than fighting it and trying to get the lower prices. ….

art critics don’t matter much anymore. If the magazine Art in America pays $200 for a review article, why listen to that writer? We have a much richer and generally more accessible guide to the value of art — namely the market itself. ….

Damien Hirst is now worth more than Dali, Picasso, and Warhol were at the same age, put together. The point isn’t whether, in aesthetic terms, he deserves that compensation. The question is whether this way of organizing the art market makes overall sense.

{ NY Sun | Continue reading }

Earlier this year, hedge-fund millionaire Daniel Loeb made a sweet trade. The 43-year-old partner at Third Point LLC had purchased a rare asset in 2003. He found a buyer in January and sold it for a 500% profit, making a quick $1 million. …

Hedge-fund managers are reinventing the art of the art deal. With their sudden riches, quest for status and big houses in need of adornment, fund managers have become some of the most active buyers and sellers in the art world.

They have been buying up hundreds of millions of dollars of paintings, sculptures and pop-art installations. They have helped turn middling artists into media stars. … where others see art, many fund managers see another market ripe for trading, buying, selling and flipping. Many invest heavily in one or two artists, to build up a “position.” They promote the value of the artists, help boost their prices and sometimes later unload pieces through a tax-favorable gift or sale.

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

“Who makes that kind of money in the stock market?” said Sender, 38, as he swiveled round the 21 screens at his desk in New York. “In the hedge-fund business these days, you’re having a great year if you make 20 percent.”

Sender revamped his hedge fund Exis Capital Management Inc. last year, returning some investors’ money after losses in 2004 and 2006. Meanwhile, the value of his art, with works by Richard Prince, Mike Kelley and Andreas Gursky, has continued to rise, quadrupling in 10 years.

Art is now his biggest single asset — 800 works that Sender values at more than $100 million. He said he recouped most of the $25 million he spent in the past 10 years on art with the sale of about 40 pieces.

Sender is a new type of financier collector, with Steven Cohen and Daniel Loeb. Their gains on works by Prince and Martin Kippenberger aren’t just dumb luck in a boom. They apply rules for buying art, as well as stocks.

Sender tries to buy the best works of artists he admires, whose pieces also are being acquired by museums and other collectors.

{ Bloomberg | Continue reading }

When a big-name artist has a gallery show at a big-name gallery like White Cube or Gagosian, his best paintings aren’t even on public view: “The new buyer has little chance of even seeing the hot paintings, which will be kept in a small private room. What is hung in public areas is available for purchase but of lesser significance.” ….

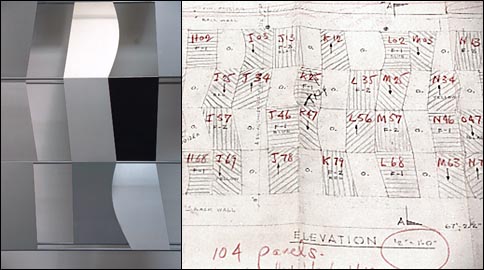

One of the things which fascinates me about the recent run-up in contemporary art prices is that it’s meant a huge change in the way that many artists work: it’s commonplace nowadays for artists to have dozens of assistants, something which was a decidedly unusual and controversial practice back in the days of Warhol. With prices for new works regularly breaking into seven figures, art has become bigger and more polished; it often uses much more expensive materials and can draw on resources which would have been unthinkable 15 years ago.

{ Portfolio | Continue reading }

To Mr. Galenson markets are what make the 20th century completely different from other eras for art. In earlier periods artists created works for rich patrons generally in the court or the church, which functioned as a monopoly. Only in the 20th century did art enter the marketplace and become a commodity, like a stick of butter or an Hermès bag. In this system, he said, breaking the rules became the most valued attribute. The greatest rewards went to conceptual innovators who frequently changed styles and invented genres. For the first time the idea behind the work of art became more important than the physical object itself.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }