What is more harmful than any vice?

{ Carl-Heinz Hargesheimer, Unter Krahnenbäumen, Cologne, around 1958, ‘Chargesheimer’ at Museum Ludwig, Cologne | Alison Brie and Aubrey Plaza in The Little Hours (2017) }

{ Carl-Heinz Hargesheimer, Unter Krahnenbäumen, Cologne, around 1958, ‘Chargesheimer’ at Museum Ludwig, Cologne | Alison Brie and Aubrey Plaza in The Little Hours (2017) }

Sophia Urista apologizes for peeing on fan. The rocker ordered the man to lie down on his back before she unbuttoned her pants, popped a squat and relieved herself on his head. Sophia Urista isn’t first rocker to urinate onstage

In the late 1940s, the British magician David Berglas started refining a trick that came to be known as “the holy grail of card magic.” […] The trick is a version of a classic plot of magic, called Any Card at Any Number. These tricks are called ACAAN in the business.

ACAAN has been around since the 1700s, and every iteration unfolds in roughly the same way: A spectator is asked to name any card in a deck — let’s say the nine of clubs. Another is asked to name any number between one and 52 — let’s say 31.

The cards are dealt face up, one by one. The 31st card revealed is, of course, the nine of clubs. Cue the gasps.

There are hundreds of ACAAN variations, and you’d be hard pressed to find a professional card magician without at least one in his or her repertoire. (A Buddha-like maestro in Spain, Dani DaOrtiz, knows about 60.) There are ACAANs in which the card-choosing spectator writes down the named card in secrecy; ACAANs in which the spectator shuffles the deck; ACAANs in which every other card turns out to be blank.

For all their differences, every ACAAN has one feature in common: At some point, the magician touches the cards. The touch might be imperceptible, it might appear entirely innocent. But the cards are always touched.

With one exception: David Berglas’s ACAAN. He would place the cards on a table and he didn’t handle them again until after the revelation and during the applause.

synthetic polymer and silkscreen ink on canvas { Andy Warhol, Are You “Different?” (Positive), 1985 }

For six years after Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, Hollywood studios avoided making films that made the Nazis look bad, because they did not want to lose access to the German market. […]

Now history seems to be repeating itself, with the studios kowtowing to Communist China. […] John Cena, star of the new Fast and Furious movie, just issued an abject apology for casually referring to Taiwan as a “country.”

“And so we had a demolition team in there for a week blowing up buildings, and the art director spent about six weeks with a guy with a wrecking ball and chain, knocking holes in the corners of things and really getting interesting ruins — which no amount of money would have allowed you to build,” Kubrick says.

Kubrick’s Hue was finished off with grillwork and other architectural accents, 200 palm trees imported from Spain and thousands of plastic plants shipped from Hong Kong. Weeds and tall yellow grass — “which look the same all over the world,” he notes — were conveniently indigenous. Four M41 tanks arrived courtesy of a Belgian army colonel who is a Kubrick fan, and historically correct S55 helicopters were leased and painted Marine green. A selection of rifles, M79 grenade launchers and M60 machine guns were obtained through a licensed weapons dealer.

Among the lowlights is a text from Depp to CAA agent Christian Carino, who previously repped Heard, in which he wrote: “[Heard is] begging for total global humiliation. She’s gonna get it. I’m gonna need your texts about San Francisco brother … I’m even sorry to ask … But she sucked [Elon Musk’s] crooked dick and he gave her some shitty lawyers … I have no mercy, no fear and not an ounce of emotion or what I once thought was love for this gold digging, low level, dime a dozen, mushy, pointless dangling overused flappy fish market … I’m so fucking happy she wants to fight this out!!! She will hit the wall hard!!! And I cannot wait to have this waste of a cum guzzler out of my life!!! I met fucking sublime little Russian here … Which makes me realize the time I blew on that 50 cent stripper … I wouldn’t touch her with a goddam glove.” […]

Depp adds, “Let’s drown her before we burn her!!! I will fuck her burnt corpse afterwards to make sure she’s dead.” […]

while shooting Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales in Australia, Depp swallowed eight ecstasy pills at once […]

He dropped $30,000 a month on wine alone. And in perhaps the most extravagant move of all, he spent $5 million to have Hunter S. Thompson’s ashes fired from a cannon hoisted atop a 153-foot tower in a fleeting tribute to the gonzo journalist. […]

a personal sound technician to handle his earpiece needs — “so he doesn’t have to learn lines,” adds the source

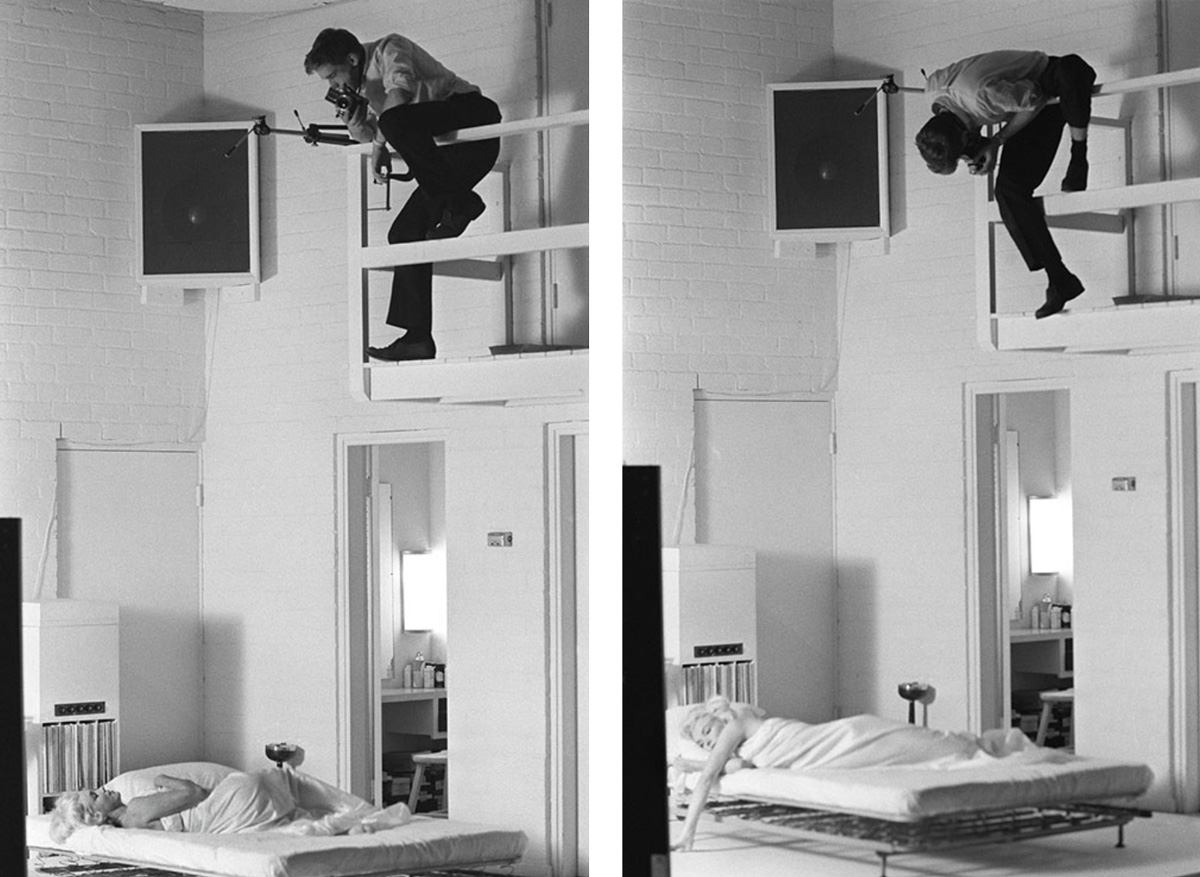

{ Marilyn Monroe poses naked in bed for photographer Douglas Kirkland on the evening of November 17th 1961 in Los Angeles | more }

I have found that most of us who want to act or write or make music or paint things or sculpt things are trying to remember, re-create, share, and pitifully hold on to a particular memory or memories that allowed us to continue living with some comfort. In everything I’ve done as an actor, I want to tell people, somehow, how it felt to feel my mother’s hand on my forehead when I was sick. I want to tell people how it felt when I protected my mother from my father’s rage. I want to tell people how it felt–how it changed my life–when my sister came to my aid, over and over again. Art is autobiography made flesh. Art is sending the message that life has merit, that people have merit. I think we should see things that make us all want to go out and live better and share the good things we have seen. I think we should, without ever meeting, let it be known that we are here to support and protect each other.

{ Marlon Brando, Interview conducted by James Grissom by telephone, 1990 }

oil and acrylic on canvas { Sebastian, Haslauer, Thug Life, 2012 }

#leavingneverland #michaeljackson pic.twitter.com/0Xq1t97pgx

— kyle Dunnigan (@kyledunnigan) March 6, 2019

movies and shows have been using the fake 555 numbers since as far back as the 1950s. […]

The number 555-2368 has risen to particularly rarefied air […] dialing 555-2368 will get you the Ghostbusters, the hotel room from Memento, Jim Rockford of The Rockford Files, and Jaime Sommers from The Bionic Woman, among others. […]

Since 1994, 555 numbers have actually been available for personal or business use. […] except for 555-0100 through 555-0199, which were held back for fictional use.

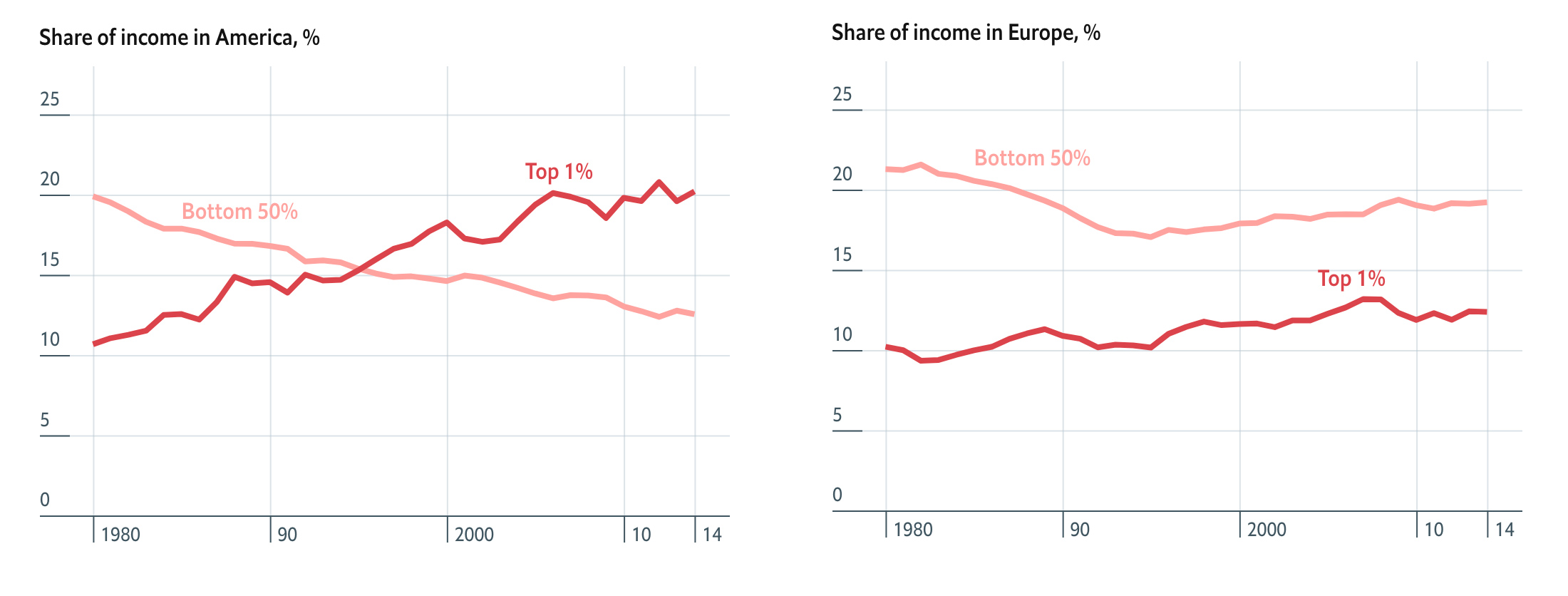

{ while ordinary people are struggling, those at the top are doing just fine. Income and wealth inequality have shot up. The top 1% of Americans command nearly twice the amount of income as the bottom 50%. The situation is more equitable in Europe, though the top 1% have had a good few decades. | The Economist | full story }

Size has been one of the most popular themes in monster movies, especially those from the 1950s. The premise is invariably to take something out of its usual context–make people small or something else (gorillas, grasshoppers, amoebae, etc.) large–and then play with the consequences. However, Hollywood’s approach to the concept has been, from a biologist’s perspective, hopelessly naïve. Absolute size cannot be treated in isolation; size per se affects almost every aspect of an organism’s biology. Indeed, the effects of size on biology are sufficiently pervasive and the study of these effects sufficiently rich in biological insight that the field has earned a name of its own: “scaling.” […]

Take any object–a sphere, a cube, a humanoid shape. […] If you change the size of this object but keep its shape (i.e., relative linear proportions) constant, something curious happens. Let’s say that you increase the length by a factor of two. Areas are proportional to length squared, but the new length is twice the old, so the new area is proportional to the square of twice the old length: i.e., the new area is not twice the old area, but four times the old area (2L x 2L).

Similarly, volumes are proportional to length cubed, so the new volume is not twice the old, but two cubed or eight times the old volume (2L x 2L x 2L). As “size” changes, volumes change faster than areas, and areas change faster than linear dimensions.

[…]

In The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), the hero is exposed to radioactive toxic waste and finds himself growing smaller and smaller. When he stops shrinking, he is about an inch tall, down by a factor of about 70 in linear dimensions. Thus, the surface area of his body, through which he loses heat, has decreased by a factor of 70 x 70 or about 5,000 times, but the mass of his body, which generates the heat, has decreased by 70 x 70 x 70 or 350,000 times. He’s clearly going to have a hard time maintaining his body temperature (even though his clothes are now conveniently shrinking with him) unless his metabolic rate increases drastically.

Luckily, his lung area has only decreased by 5,000-fold, so he can get the relatively larger supply of oxygen he needs, but he’s going to have to supply his body with much more fuel; like a shrew, he’ll probably have to eat his own weight daily just to stay alive. He’ll also have to give up sleeping and eat 24 hours a day or risk starving before he wakes up in the morning (unless he can learn the trick used by hummingbirds of lowering their body temperatures while they sleep).

Because of these relatively larger surface areas, he’ll be losing water at a proportionally larger rate, so he’ll have to drink a lot, too.

art { Agnes Martin, Untitled, 1960 }

more { Delusional misidentification syndromes have fascinated filmmakers and psychiatrists alike }

Piper Jaffray analyst Stan Meyers said animated films generally cost about $100 million to make, as well as an additional $150 million to promote.

An executive producer who wants to drastically cut costs traditionally has two choices: water and hair. Those are the most expensive things to replicate accurately via animation. It’s no mistake that the characters in Minions, the most profitable movie ever made by Universal, are virtually bald and don’t seem to spend much time in the ocean.

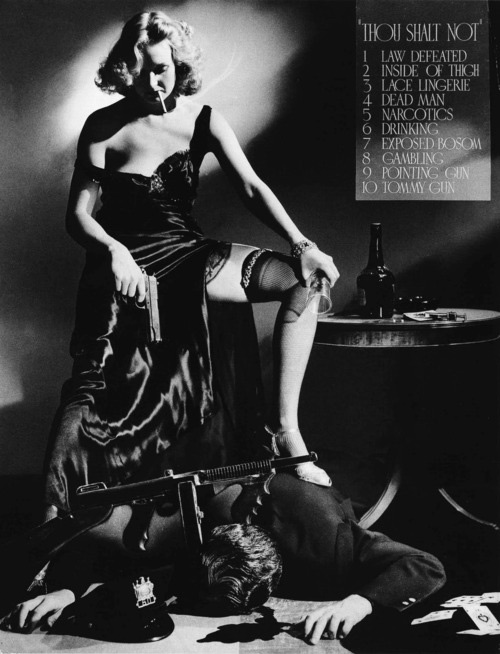

{ In 1934, the MPAA voluntarily passed the Motion Picture Production Code, more generally known as the Hays Code. The code prohibited certain plot lines and imagery from films and in publicity materials produced by the MPAA. Among other rules, there was to be no cleavage, no lace underthings, no drugs or drinking, no corpses, and no one shown getting away with a crime. A.L. Shafer, the head of photography at Columbia, took a photo that intentionally incorporated all of the 10 banned items into one image. | The Society Pages | Continue reading | More: Wikipedia }

For the student of negotiation, Breaking Bad is an absolute treasure trove, producing an incredibly complex and varied array of bargaining parties and negotiated transactions, episode after episode. What’s so fascinating about these transactions is that they draw on familiar, foundational negotiation concepts in the service of less familiar, usually illicit ends. Put another way, when we watch Walter White negotiate, we watch a mega-criminal anti-hero implement the same “value-neutral” strategies that we teach lawyers and businesspeople. […]

This article examines five negotiations, one from each season, each featuring Walter White. The close readings provided show how the five negotiations demonstrate and/or disrupt foundational negotiation concepts or skills.

{ New Mexico Law Review | PDF | More: New Mexico Law Review, Special Edition dedicated to Breaking Bad }

Movies are, for the most part, made up of short runs of continuous action, called shots, spliced together with cuts. With a cut, a filmmaker can instantaneously replace most of what is available in your visual field with completely different stuff. This is something that never happened in the 3.5 billion years or so that it took our visual systems to develop. You might think, then, that cutting might cause something of a disturbance when it first appeared. And yet nothing in contemporary reports suggests that it did. […]

What if we could go back in time and collect the reactions of naïve viewers on their very first experience with film editing?

It turns out that we can, sort of. There are a decent number of people on the planet who still don’t have TVs, and the psychologists Sermin Ildirar and Stephan Schwan have capitalised on their existence to ask how first-time viewers experience cuts. […] There was no evidence that the viewers found cuts in the films to be shocking or incomprehensible. […]

I think the explanation is that, although we don’t think of our visual experience as being chopped up like a Paul Greengrass fight sequence, actually it is.

Simply put, visual perception is much jerkier than we realise. First, we blink. Blinks happen every couple of seconds, and when they do we are blind for a couple of tenths of a second. Second, we move our eyes. Want to have a little fun? Take a close-up selfie video of your eyeball while you watch a minute’s worth of a movie on your computer or TV. You’ll see your eyeball jerking around two or three times every second.

Against those who defined Italian neo-realism by its social content, Bazin put forward the fundamental requirement of formal aesthetic criteria. According to him, it was a matter of a new form of reality, said to be dispersive, elliptical, errant or wavering, working in blocs, with deliberately weak connections and floating events. The real was no longer represented or reproduced but “aimed at.” Instead of representing an already deciphered real, neo-realism aimed at an always ambiguous, to be deciphered, real; this is why the sequence shot tended to replace the montage of representations. […]

[I]n Umberto D, De Sica constructs the famous sequence quoted as an example by Bazin: the young maid going into the kitchen in the morning, making a series of mechanical, weary gestures, cleaning a bit, driving the ants away from a water fountain, picking up the coffee grinder, stretching out her foot to close the door with her toe. And her eyes meet her pregnant woman’s belly, and it is as though all the misery in the world were going to be born. This is how, in an ordinary or everyday situation, in the course of a series of gestures, which are insignificant but all the more obedient to simple sensory-motor schemata, what has suddenly been brought about is a pure optical situation to which the little maid has no response or reaction. The eyes, the belly, that is what an encounter is … […] The Lonely Woman [Viaggio in ltalia] follows a female tourist struck to the core by the simple unfolding of images or visual cliches in which she discovers something unbearable, beyond the limit of what she can person- ally bear. This is a cinema of the seer and no longer of the agent.

What defines neo-realism is this build-up of purely optical situations (and sound ones, although there was no synchronized sound at the start of neo-realism), which are fundamentally distinct from the sensory-motor situations of the action-image in the old realism. […]

It is clear from the outset that cinema had a special relationship with belief. […] The modern fact is that we no longer believe in this world. We do not even believe in the events which happen to us, love, death, as if they only halfconcerned us. It is not we who make cinema; it is the world which looks to us like a bad film. […] The link between man and the world is broken. Henceforth, this link must become an object of belief: it is the impossible which can only be restored within a faith. Belief is no longer addressed to a different or transformed world. Man is in the world as if in a pure optical and sound situation.

{ Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2, The Time-Image, 1985 | PDF, 17.2 MB }

{ Adam Savage’s Overlook Hotel Maze Model | watch video }