From the deep pain of having to confess again and again that you never loved as you were loved

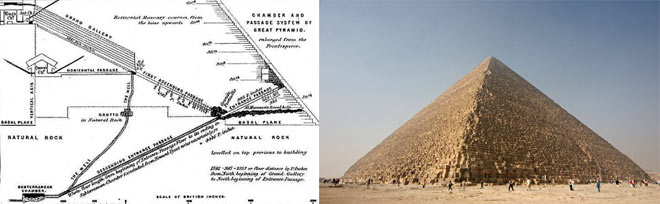

{ The Great Pyramid, built for the Pharaoh Khufu in about 2570 B.C., sole survivor of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world, and still arguably the most mysterious structure on the planet. | Inside the Great Pyramid | Smithsonian | The Secret Doors Inside the Great Pyramid | Guardians }