|

|

|

The Apple idea is that instead of the personal computer model where people own their own information, and everybody can be a creator as well as a consumer, we’re moving towards this iPad, iPhone model where it’s not really as adequate for media creation as the real media creation tools, and even though you can become a seller over the network, you have to pass through Apple’s gate to accept what you do, and your chances of doing well are very small, and it’s not really a person to person thing, it’s a business through a hub, through Apple to others, and it doesn’t really create a middle class, it creates a new kind of upper class. (…)

Google has done something that might even be more destructive of the middle class, which is they’ve said, ‘Well, since Moore’s law makes computation really, really cheap, let’s just give away the computation, but keep the data.’ And that’s a disaster.

If we enter into the kind of world that Google likes, I mean, the world that Google wants is a world where information is copied so much on the Internet that nobody knows where it came from anymore, so there can’t be any rights of authorship. However, you need a big search engine to even figure out what it is or find it. They want a lot of chaos that they can have an ability to undo. (…) When you have copying on a network, you throw out information because you lose the provenance, and then you need a search engine to figure it out again. That’s part of why Google can exist.

{ Jaron Lanier/Edge | Continue reading }

google, ideas, technology |

August 29th, 2011

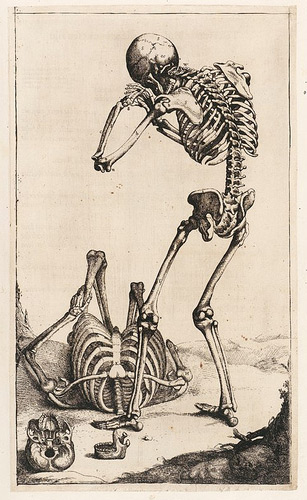

In the history of humanity there are no civilizations or cultures which fail to manifest, in one or a thousand ways, this need for an absolute that is called heaven, freedom, a miracle, a lost paradise to be regained, peace, the going beyond History. (…)

There is no religion in which everyday life is not considered a prison; there is no philosophy or ideology that does not think that we live in alienation. (…) Humanity has always had a nostalgia for the freedom that is only beauty, that is only real; life, plenitude, light.

{ Eugène Ionesco | Continue reading }

No society has been able to abolish human sadness, no political system can deliver us from the pain of living, from our fear of death, our thirst for the absolute. It is the human condition that directs the social condition, not vice versa.

{ Eugène Ionesco | Continue reading }

images { 1 | 2 }

ideas |

August 29th, 2011

Genes determine 50 percent of the likelihood that you will vote. Half of your altruism. One-quarter of your financial decisions. How do we know? Twin studies.

Researchers compare some behavior or trait in a set of pairs of monozygotic (identical) twins and a set of pairs of dizygotic (fraternal) twins. In theory, the siblings in each pair have been raised in the same way—i.e., they have “nurture” in common. But their “natures” might be different: Identical twins come from the same sperm and egg and are assumed to share their entire genomes; fraternal twins match up at only about half their genes. So if the pairs of monozygotic twins tend to share a trait more often than the pairs of dizygotic twins—be it the likelihood they will vote, a tendency toward altruism, or a strategy for managing their financial portfolios—the difference can be chalked up to genetics.

Some call this approach beautiful in its simplicity, but critics say it’s crude, potentially misleading, and based on an antiquated view of genetics. The implications of the studies are also just a little bit dangerous, because they suggest, for example, that some people just aren’t cut out for being nice to one another.

The idea of using twins to study the heritability of traits was the brainchild of the 19th-century British intellectual Sir Francis Galton. He’s not exactly the progenitor you might want for your scientific methods. Galton coined the term “eugenics” and was the inspiration for the push to manipulate human evolution through selective breeding. The movement eventually gave us forced sterilization and the most offensive passage in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court (and that’s really saying something): “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” (…)

Twin studies rest on two fundamental assumptions: 1) Monozygotic twins are genetically identical, and 2) the world treats monozygotic and dizygotic twins equivalently (the so-called “equal environments assumption”). The first is demonstrably and absolutely untrue, while the second has never been proven. (…)

Twin studies also rely on the false assumption that genetics are constant throughout one’s lifetime. Mutations and environmental factors cause measurable changes to the genome as life progresses. Charney cites the example of exercise, which can accelerate the formation of new neurons and potentially increase genetic variation among individual brain cells. By the time a pair of twins reaches middle age, it’s very difficult to make any assumptions whatsoever about the similarity of their genes.

{ Slate | Continue reading }

controversy, genes, science |

August 29th, 2011

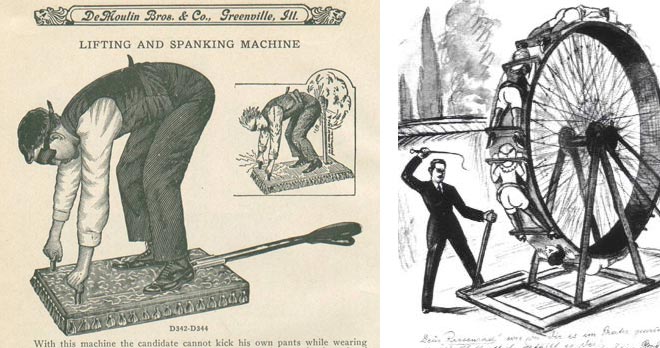

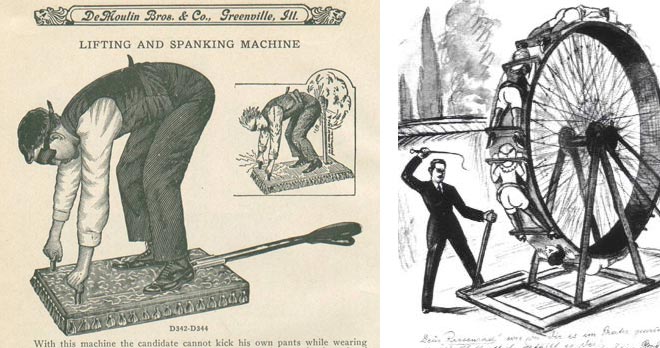

Mothers who inherited either one or two copies of a particular form of the dopamine D2 receptor gene, dubbed DRD2, cited sharp rises in spanking, yelling and other aggressive parenting methods for six to seven months after the onset of the economic recession in December 2007, sociologist Dohoon Lee of New York University reported August 22 at the American Sociological Association’s annual meeting.

Hard-line child-rearing approaches then declined for a few months and remained stable until a second drop to pre-recession levels started around June 2009, the research showed.

Mothers who didn’t inherit the gene variant displayed no upsurge in aggressive parenting styles after the recession started, Lee and his colleagues found.

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

images { 1 | 2 }

economics, genes, kids |

August 29th, 2011

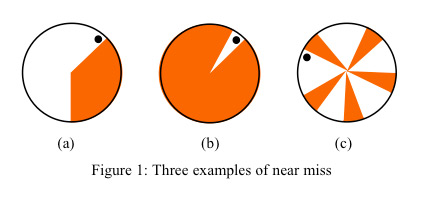

ideas, visual design |

August 29th, 2011

It’s email, it’s the Internet, it’s video games, then when texting comes along, it’s texting, and when social networking comes along, it’s social networking. So whatever the flavor of the month in terms of new technologies are, there’s research that comes out very quickly that shows how it causes our children to be asocial, distracted, bad in school, to have learning disorders, a whole litany of things.

And then the Pew Foundation and MacArthur Foundation started saying, about three or four years ago: “Wait, let’s not assume these things are hurting our kids. Let’s just look at how our kids are using media and stop with testing that’s set up from a pejorative or harmful point of view.” (…)

The phenomenon of attention blindness is real — when we pay attention to one thing, it means we’re not paying attention to something else. When we’re multitasking, what we’re actually really doing is what Linda Stone calls “continuous partial attention.” We’re not actually simultaneously paying equal attention to two things: One of the things that we’re doing is probably being done automatically, and we’re sort of cruising through that, and we’re paying more attention to the other thing. Or we’re moving back and forth between them. But any moment when there is a major new form of technology, people think it’s going to overwhelm the brain. In the 1930s there was legislation introduced to prevent Motorola from putting radios in dashboards, because it was thought that people couldn’t possibly cope with driving and listening to the radio. (…)

We used to think that as we get older we develop more neural pathways, but the opposite is actually the case. You and I have about 40 percent less neurons than a newborn infant does. (…) They are learning to process that kind of information faster. That which we experience shapes our pathways, so they’re going to be far less stressed by a certain kind of multitasking that you are or than I am, or people who may not have grown up with that.

{ Interview with Cathy N. Davidson | Salon | Continue reading }

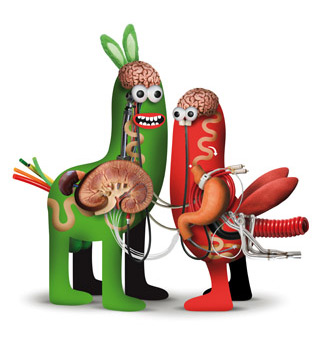

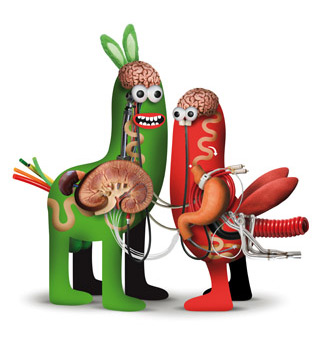

illustration { Geneviève Gauckler }

brain, kids, technology |

August 29th, 2011

The Desert of the Tartars (Il deserto dei Tartari) is a novel by Italian author Dino Buzzati, published in 1940.

The novel tells the story of a young officer, Giovanni Drogo, and his life spent guarding the Bastiani Fortress, an old, unmaintained border fortress.

The plot of the novel is Drogo’s lifelong wait for a great war in which his life and the existence of the fort can prove its usefulness. Drogo is posted to the remote outpost overlooking a desolate Tartar desert, spends his career waiting for the barbarian horde rumored to live beyond the desert.

Without noticing, Drogo finds that in his watch over the fort he has let years and decades pass and that while his old friends in the city have had children, married and lived full lives, he has come away with nothing except solidarity with his fellow soldiers in their long, patient vigil.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

screenshot { Michelangelo Antonioni, L’Avventura, 1960 }

related:

allegories, books |

August 28th, 2011

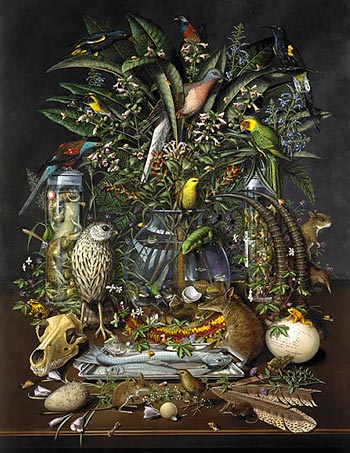

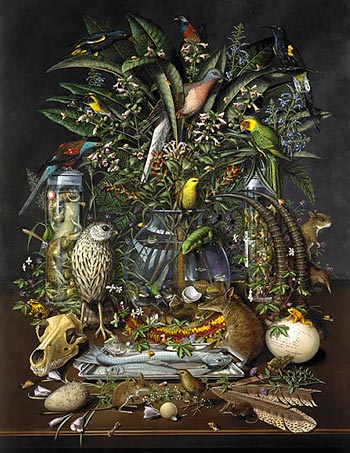

8.7 million. That is a new, estimated total number of species on Earth — the most precise calculation ever offered — with 6.5 million species found on land and 2.2 million (about 25 percent of the total) dwelling in the ocean depths.

Until now, the number of species on Earth was said to fall somewhere between 3 million and 100 million.

Furthermore, the study, published today by PLoS Biology, says a staggering 86% of all species on land and 91% of those in the seas have yet to be discovered, described and catalogued.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

painting { Isabella Kirkland }

animals, science |

August 28th, 2011

If you live on a country road you can say hello to each of the occasional persons who passes by: but obviously you can’t do this on Fifth Avenue.

As a measure of social involvemcnt for instance, we are now studying thc rcsponse to a lost child in big city and small town. A child of nine asks people to help him call his home. The graduate students report a strong difference between city and town dwellers: in the city, many more people refused to extend help to the nine-year-old. I like thc problem because there is no more meaningful measure of the quality of a culture than the manner in which it treats its children.

{ Conversation with Stanley Milgram, Psychology Today, 1974 | Continue reading | PDF }

photo { Helen Levitt, New York, c. 1940 }

kids, psychology |

August 28th, 2011

Historically, the two main types of obstacles to information discovery have been barriers of awareness, which encompass all the information we can’t access because we simply don’t know about its existence in the first place, and barriers of accessibility, which refer to the information we do know is out there but remains outside of our practical, infrastructural or legal reach. What the digital convergence has done is solve the latter, by bringing much previously inaccessible information into the public domain, made the former worse in the process, by increasing the net amount of information available to us and thus creating a wealth of information we can’t humanly be aware of due to our cognitive and temporal limitations, and added a third barrier — a barrier of motivation. (…)

If we somehow stumble upon an incredible archive of, say, digitized “rare” vinyl LP’s or unpublished manuscripts by a famous author, and it tickles our fancy, perhaps we bookmark it, perhaps we save it to Delicious or Instapaper, perhaps we take a quick skim, but more likely than not, we shove it into some cognitive corner and fail to spend time with it, exploring and learning, assuming that it’s just there, available and accessible anytime. The relationship between ease of access and motivation seems to be inversely proportional because, as the sheer volume of information that becomes available and accessible to us increases, we become increasingly paralyzed to actually access all but the most prominent of it — prominent by way of media coverage, prominent by way of peer recommendation, prominent by way of alignment with our existing interests. This is why information that isn’t rare in technical terms, in terms of being free and open to anyone willing to and knowledgeable about how to access it, may still remain rare in practical terms, accessed by only a handful of motivated scholars.

{ Nieman Journalism Lab | Continue reading }

ideas, media, technology |

August 28th, 2011

The practice of naming storms (tropical cyclones) began years ago in order to help in the quick identification of storms in warning messages because names are presumed to be far easier to remember than numbers and technical terms. (…)

In the beginning, storms were named arbitrarily. An Atlantic storm that ripped off the mast of a boat named Antje became known as Antje’s hurricane. Then the mid-1900’s saw the start of the practice of using feminine names for storms.

In the pursuit of a more organized and efficient naming system, meteorologists later decided to identify storms using names from a list arranged alpabetically. Thus, a storm with a name which begins with A, like Anne, would be the first storm to occur in the year.

Before the end of the 1900’s, forecasters started using male names for those forming in the Southern Hemisphere. (…)

Since 1953, Atlantic tropical storms have been named from lists originated by the National Hurricane Center. (…) Six lists are used in rotation. Thus, the 2008 list will be used again in 2014.

{ World Meteorological Organization | Continue reading }

related { This isn’t the first time we’ve met Hurricane Irene | As the storm’s outer bands reached New York on Saturday night, two kayakers capsized and had to be rescued off Staten Island }

U.S., incidents, science |

August 27th, 2011

I call it “Broks’s paradox”: the condition of believing that the mind is separate from the body, even though you know this belief to be untrue. (…)

Alexander Vilenkin, a physicist, believes that our universe is just one of an infinite number of similar regions. But “it follows from quantum mechanics” that the number of histories that can be played out in them is finite. The upshot of this crossplay of finitudes and infinities is that every possible history will play out in an infinite number of regions, which means there should be an infinite number of places with histories identical to our own down to the atomic level. “I find this rather depressing,” says Vilenkin, “but it is probably true.” The cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman, on the other hand, believes that “consciousness and its contents are all that exists,” the physical universe being “among the humbler contents of consciousness.” (…)

This brings us to death. The psychologist Jesse Bering believes we will never get our heads around the idea. He calls it “Unamuno’s paradox,” after the Spanish existentialist Miguel de Unamuno, who was troubled not so much by the prospect of his own death as by his inability in life to get any kind of imaginative purchase on what the state of being dead would be “like.”

{ Prospect | Continue reading }

photo { Lissy-Laricchia }

ideas, neurosciences |

August 26th, 2011

This study examines how men and women define romantic love. It uses surveys to find some commonalities and differences among residents in the US, Lithuania and Russia.

Researchers found that residents of all three countries listed “being together” as their top requirement of romantic love. From there, the notion of romantic love seemed to diverge with the US respondents having different views than Lithuanian and Russian counterparts. The importance of friendship in romantic love and the time it takes to perceive falling in love are two key differences in how people see romantic love. The idea that romantic love was temporary and inconsequential was frequently cited by Lithuanian and Russian respondents unlike the Americans.

Expressions of ‘comfort/love’ and ‘friendship’ were frequently cited by the U.S. informants and seldom to never by the Eastern European informants. Results suggested it takes Americans longer to fall in love.

{ SAGE | Continue reading }

relationships |

August 26th, 2011

In a new book, Levinson explains how local mom-and-pop stores — with their limited selections, high prices and nonstandard packaging — paved the way for national chains like the A&P to swoop in and dominate the grocery industry. (…)

The A&P, which originally focused on the tea market, opened its first small grocery store in 1912. Unlike traditional mom-and-pop stores, the A&P had no telephone, no credit lines and no delivery options. They also had lower prices.

“People figured out they could save money by shopping there,” says Levinson. “It stocked only items that were fast-sellers, so it wasn’t stuck with an inventory of products no one was buying. It had limited hours. It had a single employee. … They found a way to sell groceries cheaper. … Within eight years, this approach turned their company into the largest retailer in the world.”

By 1930, the Hartford family, which owned A&P, had opened up almost 16,000 more stores. The stores themselves also expanded in both size and selection. (…)

Controlling both the retail store and the supply chain gave the A&P a huge advantage over corner grocery stores because the A&P could run the factories at a lower cost. In addition, the A&P started to bypass wholesalers and go directly to distributors for various products.

{ NPR | Continue reading }

economics, flashback |

August 26th, 2011

After returning from holiday, it’s likely you felt that the journey home by plane, car or train went much quicker than the outward journey, even though in fact both distances and journey are usually the same. So why the difference?

According to a new study it seems that many people find that, when taking a trip, the way back seems shorter. The findings suggest that this effect is caused by the different expectations we have, rather than being more familiar with the route on a return journey. (…)

“The ‘return trip effect’ also existed when respondents took a different, but equidistant, return route. You do not need to recognize a route to experience the effect.”

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Mitch Epstein, Kennedy Airport, New York City, 1973 }

psychology, transportation |

August 26th, 2011

Take a piece of paper. Crumple it. Before you sink a three-pointer in the corner wastebasket, consider that you’ve just created an object of extraordinary mathematical and structural complexity, filled with mysteries that physicists are just starting to unfold.

“Crush a piece of typing paper into the size of a golf ball, and suddenly it becomes a very stiff object. The thing to realize is that it’s 90 percent air, and it’s not that you designed architectural motifs to make it stiff. It did it itself,” said physicist Narayan Menon of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “It became a rigid object. This is what we are trying to figure out: What is the architecture inside that creates this stiffness?”

{ Wired | Continue reading }

image { Richard Smith, Diary, 1975 }

mystery and paranormal, science |

August 26th, 2011

Last year, for the first time in history, a billion cars and trucks hit the road. (…)

What’s stunning is how far countries like China and India still have to go. Right now, there’s one car in China for every 17.2 people, compared with one car for every 1.3 people in the United States. If China caught up to the U.S. ownership rate, the country would field a billion vehicles all by itself.

{ Washington Post | Continue reading }

photo { Laura Helms }

economics, motorpsycho |

August 26th, 2011

{ The most valuable coin in the world sits in the lobby of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in lower Manhattan. It’s Exhibit 18E, secured in a bulletproof glass case with an alarm system and an armed guard nearby. The 1933 Double Eagle, considered one of the rarest and most beautiful coins in America, has a face value of $20—and a market value of $7.6 million. | How did a Philadelphia family get hold of $40 million in gold coins, and why has the Secret Service been chasing them for 70 years? | Businessweek | full story }

U.S., economics, mystery and paranormal |

August 26th, 2011

photogs |

August 25th, 2011

We make decisions all our lives—so you’d think we’d get better and better at it. Yet research has shown that younger adults are better decision makers than older ones. Some Texas psychologists, puzzled by these findings, suspected the experiments were biased toward younger brains.

So, rather than testing the ability to make decisions one at a time without regard to past or future, as earlier research did, these psychologists designed a model requiring participants to evaluate each result in order to strategize the next choice, more like decision making in the real world.

The results: The older decision makers trounced their juniors.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Rory Watson }

psychology |

August 25th, 2011