The error of optimism dies in the crisis

“When you sell a stock,” I asked him, “who buys it?” He answered with a wave in the vague direction of the window, indicating that he expected the buyer to be someone else very much like him. That was odd: because most buyers and sellers know that they have the same information as one another, what made one person buy and the other sell? Buyers think the price is too low and likely to rise; sellers think the price is high and likely to drop. The puzzle is why buyers and sellers alike think that the current price is wrong. (…)

In a paper titled “Trading Is Hazardous to Your Wealth,” Odean and his colleague Brad Barber showed that, on average, the most active traders had the poorest results, while those who traded the least earned the highest returns. (…)

Individual investors like to lock in their gains; they sell “winners,” stocks whose prices have gone up, and they hang on to their losers. Unfortunately for them, in the short run going forward recent winners tend to do better than recent losers, so individuals sell the wrong stocks. They also buy the wrong stocks. Individual investors predictably flock to stocks in companies that are in the news. Professional investors are more selective in responding to news. These findings provide some justification for the label of “smart money” that finance professionals apply to themselves.

Although professionals are able to extract a considerable amount of wealth from amateurs, few stock pickers, if any, have the skill needed to beat the market consistently, year after year. (…) At least two out of every three mutual funds underperform the overall market in any given year.

‘Editing process online is zero, pretty much.’ –Adam Moss

{ Cory Arcangel, Super Mario Clouds (2002-) | Super Mario Clouds is an old Mario Brothers cartridge which I modified to erase everything but the clouds. }

No one sleeps in the hanging garden

Abu Dhabi — A dramatic fall in traffic accidents this week has been directly linked to the three-day disruption in BlackBerry services.

In Dubai, traffic accidents fell 20 per cent from average rates on the days BlackBerry users were unable to use its messaging service. In Abu Dhabi, the number of accidents this week fell 40 per cent and there were no fatal accidents.

On average there is a traffic accident every three minutes in Dubai, while in Abu Dhabi there is a fatal accident every two days.

The chains of wedlock are so heavy that it takes two to carry them; sometimes three.

Jealousy has often been considered a dangerous emotion because it motivates a wide range of behavior including spousal violence and abuse. It is therefore a major task of jealousy research to identify potential determinants of jealousy-motivated behavior. One such potential determinant is the intensity of the jealousy feeling. It appears reasonable to assume that mild jealousy feelings promote rather innocuous mate retention tactics such as heightened vigilance. In contrast, very intense feelings are more likely to evoke ferocious reactions including violence and abuse.

Several determinants of jealousy intensity have been identified. First, sneaking suspicions of a partner’s infidelity appear to result in mild, anxious-insecurity like jealousy feelings, whereas the certainty of actual infidelity is associated with intense, rage-like jealousy feelings.

Secondly, based on evolutionary psychological considerations, Buunk and his colleagues provided substantial empirical evidence that rival characteristics affect jealousy intensity. These authors found that a (potential) rival’s high physical attractiveness elicits more jealousy in women than in men. In contrast, a (potential) rival high in social and physical dominance and social status evokes more jealousy in men than in women.

Third, a fundamental factor contributing to the intensity of jealousy concerns the infidelity type the partner engages in. Empirical evidence continues to accumulate confirming the evolutionary psychological hypothesis that men respond with more intense jealousy than women to a mate’s sexual infidelity whereas, conversely, women respond with more intense jealousy than men to a mate’s emotional infidelity.

As the unfaithful partner most likely tries to conceal his or her infidelity, the jealousy mechanism often needs to rely on indirect evidence from which a mate’s infidelity can be inferred. An important source of such indirect evidence consists of sudden and conspicuous changes in the partner’s behavior. (…) However, the sudden and conspicuous changes in the partner’s behavior as factors contributing to jealousy intensity and thus determinants of jealousy-motivated behavior have several limitations. First, these behavioral changes are often ambiguous with respect to the infidelity type (e.g., the clothing style suddenly changes; he or she stops returning your phone calls), thus presumably requiring complex inference processes that are prone to errors. Second, some if not most of these behavioral cues to infidelity were certainly not available during our ancestors’ past, (e.g., the clothing style suddenly changes; he or she stops returning your phone calls). As a consequence, they could not have shaped the jealousy mechanism during its evolutionary history. (…)

These considerations raise the question whether there are possible additional cues to infidelity that do not suffer from the limitations mentioned above. The present study picks up this question and examines a hitherto neglected but fundamental proximate contextual factor in jealousy research: The spatial distance between the persons involved in the “eternal triangle” (Buss, 2000), that is the partner, the potential rival and the jealous person. Spatial distance between the three persons (a) was recurrently available to our ancestors and thus could have been exploited by the jealousy mechanism throughout our evolutionary past, (b) can be clearly detected, (c) is not ambiguous and thus does not require complex inferential processes, (d) informs rather directly about appropriate mate guarding behavior (e.g., moving closer to the partner; increasing the distance between the partner and the potential rival or stepping between the partner and the potential rival).

painting { Fragonard, The Stolen Kiss, c. 1786-1788 }

‘Yes it’s you.’ –Sweet Charles

He is one of New York’s busiest casting directors, yet very few know of his work. (…)

For some 15 years, Mr. Weston has been providing the New York Police Department with “fillers” — the five decoys who accompany the suspect in police lineups.

Detectives often find fillers on their own, combing homeless shelters and street corners for willing participants. In a pinch, police officers can shed their uniforms and fill in. But in the Bronx, detectives often pay Mr. Weston $10 to find fillers for them.

A short man with a pencil-thin beard, Mr. Weston seems a rather unlikely candidate for having a working relationship with the Police Department, even an informal one. He is frequently profane, talks of beating up anyone who crosses him, and spends quite a bit of his money on coconut-flavored liquor.

But Mr. Weston points out that he has never failed to produce lineups when asked, no matter what time of night. “I never say no to money,” he said.

Across the nation, police lineups are under a fresh round of legal scrutiny, as recent studies have suggested that mistaken identifications in lineups are a leading cause of wrongful convictions, and that witnesses can be steered toward selecting the suspect arrested by the police.

But for all the attention that lineups attract in legal circles, Mr. Weston’s role in finding lineup fillers is largely unknown. Few defense lawyers and prosecutors, though they spar over the admissibility of lineups in court, have heard of him.

Sudden hush across the water, and we’re here again

In theory, the relationship between rainfall and tree cover should be straightforward: The more rain a place has, the more trees that will grow there. But small studies have suggested that changes can occur in discrete steps. Add more rain to a grassy savanna, and it stays a savanna with the same percentage of tree cover for quite some time. Then, at some crucial amount of extra rainfall, the savanna suddenly switches to a full-fledged forest.

But no one knew whether such rapid transformations happened on a global scale. (…) Holmgren’s group identified three distinct ecosystem types: forest, savanna, and a treeless state. Forests typically had 80 percent tree cover, while savannas had 20 percent trees and the “treeless” about 5 percent or less. Intermediate states — with, say, 60 percent tree cover — are extremely rare, Holmgren says. Which category a particular landscape fell into depended heavily on rainfall.

Fire may be another important factor in determining tree cover.

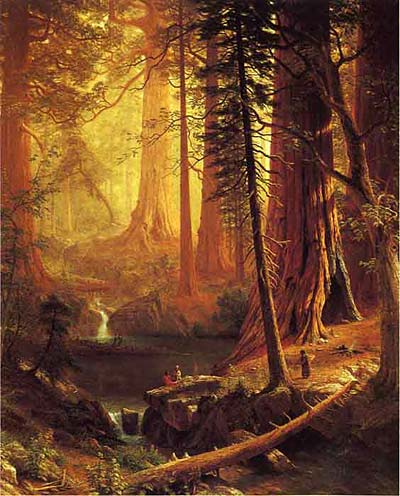

painting { Albert Bierstadt, Giant Redwood Trees of California, 1874 }

When it’s suddenly gone and there’s nothing left to prove it was ever there

Hume’s account of the self is to be found mainly in one short and provocative section of his Treatise of Human Nature – a landmark work in the history of philosophy, published when Hume was still a young man. What Hume says here (in “Of Personal Identity”) has provoked a philosophical debate which continues to this day. What, then, is so novel and striking about Hume’s account that would explain its fascination for generations of philosophers?

One of the problems of personal identity has to do with what it is for you to remain the same person over time. In recalling your childhood experiences, or looking forward to your next holiday, it appears that in each case you are thinking about one and the same person – namely, you. But what makes this true? The same sort of question might be raised about an object such as the house in which you’re now living. Perhaps it has undergone various changes from the time when you first moved in – and you may have plans to alter it further. But you probably think that it is the same house throughout. So how is this so? It helps in this case that at least we’re pretty clear about what it is for something to be a house (namely, a building with a certain function), and therefore to be the same house through time. But what is it for you to be a person (or self)? This is the question with which Hume begins. He is keen to dismiss the prevailing philosophical answer to this question – (…) that underlying our various thoughts and feelings is a core self: the soul, as it is sometimes referred to. (…)

How, then, does Hume respond to this view of the self? (…) Hume concludes memorably that each of us is “nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions”. We might be inclined to think of the mind as a kind of theatre in which our thoughts and feelings – or “perceptions” – make their appearance; but if so we are misled, for the mind is constituted by its perceptions. This is the famous “bundle” theory of the mind or self that Hume offers as his alternative to the doctrine of the soul.

Flesh and blood and the first kiss, the first colors

In 2006, two researchers – Janine Willis and Alexander Todorov – demonstrated that it only takes 1/10th of a second to form an impression of attractiveness, trustworthiness, competence and aggressiveness. Quite frighteningly, more time doesn’t make a difference – that 1/10th of a second’s impression merely becomes further cemented over the course of the first second.

And in fact, 100ms may be being generous – the same year Bar et al. demonstrated that consistent first impressions were made after 39ms. However, this latter study showed an opportunity for us to breathe a sigh of relief: impressions are not consistent on intelligence: because unlike attractiveness, trustworthiness, competence and aggressiveness, there is no short-term affect on survival from intelligence.

photo { Erica Segovia }

The smaller the attendance the bigger the history. There were 12 people at the Last Supper. Half a dozen at Kitty Hawk. Archimedes was on his own in the bath.

What is the art of immersion? The focus of the book is on how the internet is changing storytelling; and the idea is really that every time a new medium comes along, it takes people 20 or 30 years to figure out what to do with it, to figure out the grammar of that medium. The motion picture camera was invented around 1890 and it was really about 1915 before the grammar of cinema–all the things we take for granted now, like cuts and point-of-view shots and fades and pans–were consolidated into first what we would recognize as feature films. Birth of a Nation being the real landmark. It wasn’t the first film that had these characteristics but it was the first film to use all of them and that people settled on that really made a difference. I think we are not quite there yet with the internet but we can see the outlines of what is happening, what is starting to emerge; and it’s very different from the mass media that we’ve been used to for the past 150 years. (…)

NotSoSerious.com–the campaign in advance of the Dark Knight. This was what’s known as an alternate reality game. This was a particularly large-scale example that took place over a period of about 18 months. Essentially the purpose of it was to create this experience that kind of started and largely played out online but also in the real world and elsewhere that would familiarize people with the story and the characters of the Dark Knight. In particular with Heath Ledger as the Joker. Build enthusiasm and interest in the movie in advance of its release. On one level it was a marketing campaign; on another level it was a story in itself–a whole series of stories. It was developed by a company called 42 Entertainment, based in Pasadena and headed by a woman named Susan Bonds who was interestingly enough educated and worked first as a Systems Engineer and spent quite a bit of time at Walt Disney Imagineering, before she took up this. It’s a particularly intriguing example of storytelling because it really makes it possible or encourages the audience to discover and tell the story themselves, online to each other. For example, there was one segment of the story where there were a whole series of clues online that led people to a series of bakeries in various cities around the United States. And when the got to the bakery, the first person to get there in each of these cities, they were presented with a cake. On the icing to the cake was written and phone number and the words “Call me.” When they called, the cake started ringing. People would obviously cut into the cake to see what was going on, and inside the cake they found a sealed plastic pouch with a cell phone and a series of instructions. And this led to a whole new series of events that unfolded and eventually led people to a series of screenings at cities around the country of the first 7 minutes of the film, where the Heath Ledger character is introduced. (…)

The thing about Lost was it was really a different kind of television show. What made it different was not the sort of gimmicks like the smoke monster and the polar bear–those were just kind of icing. What really made it different was that it wasn’t explained. In the entire history of television until quite recently, just the last few years, the whole idea of the show has been to make it really simple, to make it completely understandable so that no one ever gets confused. Dumb it down for a mass audience. Sitcoms are just supposed to be easy. Right. Lost took exactly the opposite tack, and the result was–it might not have worked 10 years ago, but now with everybody online, we live in an entirely different world. The result was people got increasingly intrigued by the essentially puzzle-like nature of the show. And they tended to go online to find out things about it. And the show developed a sort of fanatical following, in part precisely because it was so difficult to figure out.

There was a great example I came across of a guy in Anchorage, Alaska who watched the entire first season on DVD with his girlfriend in a couple of nights leading up to the opening episode of Season 2. And then he watched the opening episode of Season 2 and something completely unexpected happened. What is going on here? So he did what comes naturally at this point, which was to go online and find out some information about it. But there wasn’t really much information to be found, so he did the other thing that’s becoming increasingly natural, which was he started his own Wiki. This became Lostpedia–it was essentially a Wikipedia about Lost and it now has tens of thousands of entries; it’s in about 20 different languages around the world. And it’s become such a phenomenon that occasionally the people who were producing the show would themselves consult it–when their resident continuity guru was not available.

What had been published in very small-scale Fanzines suddenly became available online for anybody to see. (…)

The amount of time people devote to these beloved characters and stories–which are not real, which doesn’t matter really at all, which was one of the fascinating things about this whole phenomenon–it couldn’t have happened in 1500. Not because of the technology–of course they are related–but you’d starve to death. The fact that people can devote hundreds of hundreds of hours personally, and millions can do this says something about modern life that is deep and profound. Clay Shirky, who I believe you’ve interviewed in the past, has the theory that television arrived just in time to soak up the excess leisure time that was produced by the invention of vacuum cleaners and dishwashers and other labor-saving devices.

‘Time is an illusion, lunchtime doubly so.’ –Douglas Adams

Today hardly anyone notices the equinox. Today we rarely give the sky more than a passing glance. We live by precisely metered clocks and appointment blocks on our electronic calendars, feeling little personal or communal connection to the kind of time the equinox once offered us. Within that simple fact lays a tectonic shift in human life and culture.

Your time — almost entirely divorced from natural cycles — is a new time. Your time, delivered through digital devices that move to nanosecond cadences, has never existed before in human history. As we rush through our overheated days we can barely recognize this new time for what it really is: an invention. (…)

Mechanical clocks for measuring hours did not appear until the fourteenth century. Minute hands on those clocks did not come into existence until 400 years later. Before these inventions the vast majority of human beings had no access to any form of timekeeping device. Sundials, water clocks and sandglasses did exist. But their daily use was confined to an elite minority.

{ Adam Frank/NPR | Continue reading }

The 12-hour clock can be traced back as far as Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: Both an Egyptian sundial for daytime use and an Egyptian water clock for night time use were found in the tomb of Pharaoh Amenhotep I. Dating to c. 1500 BC, these clocks divided their respective times of use into 12 hours each.

The Romans also used a 12-hour clock: daylight was divided into 12 equal hours (of, thus, varying length throughout the year) and the night was divided into four watches. The Romans numbered the morning hours originally in reverse. For example, “3 am” or “3 hours ante meridiem” meant “three hours before noon,” compared to the modern usage of “three hours into the first 12-hour period of the day.”

Also: The terms “a.m.” and “p.m.” are abbreviations of the Latin ante meridiem (before midday) and post meridiem (after midday).

‘How now? a rat? Dead, for a ducat, dead!’ –Shakespeare

The life cycle of the parasite Toxoplasma gondii goes like this: Toxoplasma reproduces inside the intestine of a cat, which sheds the parasite in its feces. Rats then ingest the parasite when they consume food or water contaminated with cat feces. The parasite takes up residence in the rat’s brain and, once the rat gets eaten by a cat, it starts the cycle all over again.

Researchers have known for a few years that a rat infected with Toxoplasma loses its natural response to cat urine and no longer fears the smell. And they know that the parasite settles in the rat’s amygdala, the part of the brain that processes fear and emotions. Now a new study in the journal PLoS ONE adds another bizarre piece to the tale: When male rats infected with Toxoplasma smell cat urine, they have altered activity in the fear part of the brain as well as increased activity in the part of the brain that is responsible for sexual behavior and normally activates after exposure to a female rat.

The double messages of “you smell a cat but he’s not dangerous” and “that cat is a potential mate” lure the rat into the kitty’s deadly territory, just what the parasite needs to reproduce.

‘I just follow my characters around and write what they say.’ –Faulkner

Pitchfork: You co-directed your video for “Vanessa” from the Darkbloom EP. What was the inspiration for it?

G: That was a real K-pop-influenced video. The budget was $60, which all went to alcohol. We literally planned it the night before. I just got a bunch of my friends to drink a lot and was like, “We’re going to do dance moves.” We did it in a couple of hours. I almost didn’t care what it looked like; I just wanted it to look like everyone’s having a good time. I also wanted it to be kind of creepy, too, hence the backward stuff. I want to make a video for every track on Visions, and right now I’m starting one on 35mm for “Oblivion”. It’s going to be sick. All my brother’s friends play varsity sports and are buff, so we’re going to have them spritzed in oil, working out with strobe lights in it.

{ Pitchfork | Interview with Claire Boucher, the 23-year-old singer and producer from Montreal who goes by Grimes | Continue reading | Thanks Colleen }

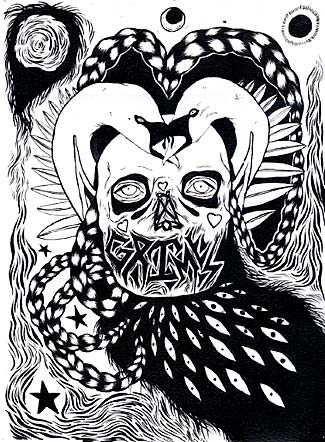

illustration { Claire Boucher }

I’m afraid of losing my obscurity. Genuineness only thrives in the dark. Like celery.

{ With brain donation, unlike other types of organ donation, it’s important to have information about the donor and their mental functioning during life. | NewScientist | full story }

Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto

Three pathways to disinhibition:

• Social Power: Powerful people are used to relative abundance and have an increased inclination to pursue potential rewards. Because the experience of power increases a “goal and reward focus,” individuals feel less restrained in expressing their current motives – regardless of the social implications.

• Intoxication: Consuming too much alcohol decreases cognitive resources, and only the most prominent cues will guide behavior in this state. Thus, pre-existing attitudes and personality traits may be expressed more freely, such as aggressive tendencies or risky sexual decision-making. At the same time, however, inebriated individuals tend to be more helpful than sober counterparts when the situation calls for heroism.

• Anonymity: A cloaked identity serves to reduce social desirability concerns and external constraints on action. As such, an individual may be less inclined to maintain usual levels of social acceptance. This could result in higher levels of honesty and self-disclosure – or heightened aggression and verbal abuse – in an anonymous chatroom.

Each of these processes - a reward focus, cognitive exhaustion, and lack of social concerns - block the same neurological system - the Behavioral Inhibition System - that regulates behavior. The combination of these forces (e.g., a powerful person who has been imbibing all night and then goes into an anonymous chat room) is likely to produce the most disinhibition.

related { When the economy is down, alcohol consumption goes up }

photo { Craig Mammano }

‘It is not reason which is the guide of life, but custom.’ –Hume

My topic is the shift from ‘architect’ to ‘gardener’, where ‘architect’ stands for ’someone who carries a full picture of the work before it is made’, to ‘gardener’ standing for ’someone who plants seeds and waits to see exactly what will come up’. I will argue that today’s composer are more frequently ‘gardeners’ than ‘architects’ and, further, that the ‘composer as architect’ metaphor was a transitory historical blip.

{ Brian Eno/Edge }

Sunlight is the best disinfectant

Kings, queens and dukes were always richer and more powerful than the population at large, and would surely have liked to use their money and power to lengthen their lives, but before 1750 they had no effective way of doing so. Why did that change? While we have no way of being sure, the best guess is that, perhaps starting as early as the 16th century, but accumulating over time, there was a series of practical improvements and innovations in health. (…)

The children of the royal family were the first to be inoculated against smallpox (after a pilot experiment on condemned prisoners), and Johansson notes that “medical expertise was highly priced, and many of the procedures prescribed were unaffordable even to the town-dwelling middle-income families in environments that exposed them to endemic and epidemic disease.” So the new knowledge and practices were adopted first by the better-off—just as today where it was the better-off and better-educated who first gave up smoking and adopted breast cancer screening. Later, these first innovations became cheaper, and together with other gifts of the Enlightenment, the beginnings of city planning and improvement, the beginnings of public health campaigns (e.g. against gin), and the first public hospitals and dispensaries, they contributed to the more general increase in life chances that began to be visible from the middle of the 19th century.

Why is this important? The absence of a gradient before 1750 shows that there is no general health benefit from status in and of itself, and that power and money are useless against the force of mortality without weapons to fight. (…)

Men die at higher rates than women at all ages after conception. Although women around the world report higher morbidity than men, their mortality rates are usually around half of those of men. The evidence, at least from the US, suggests that women experience similar suffering from similar conditions, but have higher prevalence of conditions with higher morbidity, and lower prevalence of conditions with higher mortality so that, put crudely, women get sick and men get dead.

{ Angus Deaton, Center for Health and Wellbeing, Princeton University | Continue reading | PDF }

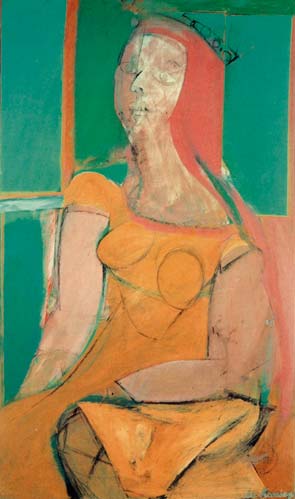

artwork { Willem de Kooning, Queen of Hearts, 1943-46 }

For you have five trees in Paradise which do not change, either in summer or in winter, and their leaves do not fall

The genius behind the square tree was Robert Falls, who in the late 1980s was a PhD candidate in the U. of B.C. botany department. Falls noticed that some tree trunks exposed to high winds had become less round in cross section — they’d grown thicker on their leeward and windward sides to buttress themselves. Falls theorized that flexing of the bark by the wind encouraged the cambium— the layer of growth cells just beneath the bark — to produce extra wood. To test his theory, Falls subjected trees to what he thought might be comparable stress by scarring them with surgical tools. Sure enough, more wood grew at the site of the scars.

Hearing the news, a professor in the university’s wood science department suggested Falls try using this discovery to grow trees with a square cross section. Square trees would be a boon to the lumber industry. Since boards are flat and trees are round, only 55 to 60 percent of the average log can be sawed into lumber — the rest winds up getting turned into paper pulp and the like, or just gets thrown away. So Falls obligingly scarred seedlings of several species (western redcedar, black cottonwood, and redwood) at 90-degree intervals around their trunks. The trees responded as hoped, becoming “unmistakably squarish,” he tells me. (…)

Square trees were just the start. In 1989 Falls was awarded a Canadian patent for an “Expanded Wood Growing Process,” a bland title that fails to capture the revolutionary nature of the concept. Square trees by comparison are a mere novelty. The young scientist had come up with a way to grow boards.

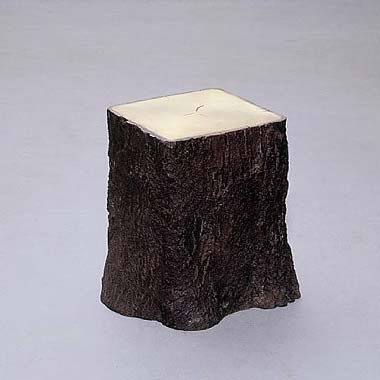

image { Bo Young Jung & Emmanuel Wolfs, Square Tree Trunk stool II, 2009 | bronze }