My problem is Judy loves chick flicks.

I can’t forget when she forced me to see Brokeback Mountain and insisted that I look at icky scenes that no red-blooded American boy like me should have to see.

No man (and that includes Alan Alda) is so sensitive that he can sit through these long-winded duller-than-dirt chick movies. And yet no man is ready to admit how much he hates these films. Why? For fear of sexual reprisals delivered in the form of “Not this year, dear. I have a headache.”

And do you want to know how far this sexual intimidation has come? I still have nightmares about the night in 1996 when we went to see The English Patient (the single worst movie I ever sat through in my life).

I remember the night Judy and I went to see this movie. The East Hampton Cinema was filled with couples. The women all fluttery . . . the men all reserved.

I remember looking at Judy and, quite frankly, I was turned on. I figured it was an early movie and the night was young and so was Judy. I planned on drinks and soft music and, you know . . .

Judy gets very emotional at movies and that night she was in fine form. She started to sob the minute they put on that computer-animated horror that tells you to eat popcorn and drink Coca-Cola but don’t talk, etc., etc.

“Judy,” I whispered. “Why are you crying? The movie hasn’t started yet.”

“I know but it’s going to be so . . . so . . . sad.”

Well, in The English Patient, Ralph Fiennes plays a Nazi who is badly burned in a plane crash. So the whole movie consists of this guy who I swear is so burned that he looks exactly like the creature in that monster film of the ’50s, Creature from the Black Lagoon.

I knew from the beginning of the movie he was going to die. Spending three hours watching a guy who is made up to look like a burned-to-a-crisp monster dying is not my idea of a fun Saturday night.

There were a lot of other story lines and characters in the movie – one duller than the other. The burned guy kept remembering this love affair he had with this married woman who was, you guessed it, his best friend’s wife.

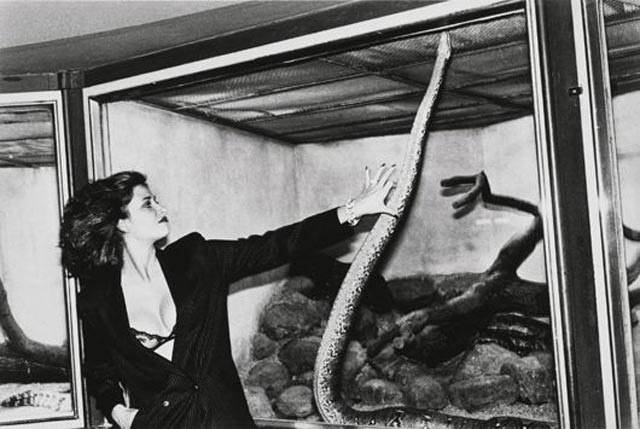

Well, this was not one of those wham-bam affairs. No sir. This was slow. So slow that they managed to do the impossible . . . make sex boring. And the more the nurse who was taking care of the guy who was burned to a crisp heard the story of the affair, the more she was interested in climbing into bed with the crisp.

At one point I said to myself, “If she goes near this guy, I’m going to be sick. The only thing that is going to save me from throwing up is that this movie is so boring I’m starting to doze off.”

That’s when Judy poked me.

“Isn’t this wonderful?” she declared with tears streaming down her face. Her tone told me that if I told the truth I could forget about the drinks and soft music later. So I did what any red-blooded young man would do under the circumstances. I lied. “It’s wonderful . . . wonderful. It’s the best thing I’ve seen in years,” I said.

“How come you’re not crying?” she whispered.

“Well, to tell you the truth, I was so caught up in the story that I guess I forgot to cry,” I said.

{ Jerry Della Femina | Continue reading }