science

Although real ‘clock measured’ time is passing at a constant rate, experience tells us that our subjective sense of the amount of time that has occurred, or the speed at which time is passing, can vary, leading to distortions in the passage of time. When we feel like less time has occurred than actually has, time feels like it has speeded up. When we feel like more has occurred than actually has, time feels like it has slowed down.

Despite being commonly experienced, the mechanisms behind distortions of the passage of time are underresearched and, as a result, poorly understood. Anecdotal accounts imply that our experience of time is influenced by our emotions and the activities we engage in: ‘time flies when you’re having fun’, but not when an car is hurtling towards you.

It is not only enjoyment and fear that affect how quickly time appears to be passing: other alterations in subjective consciousness have similar effects. The consumption of drugs and alcohol has long been known to warp time experiences. […]

Having experienced distortions in the passage of time whilst under the influence of drugs and alcohol, there is some concern amongst users about whether any effects could be permanent. Heavy drug and alcohol use can result in long-term neurological damage (Harper, 2009) and impaired cognitive function (Fisk & Montgomery, 2009), both of which may alter timing ability even when drug use has ceased. Chronic cocaine and amphetamine use reduces dopamine D2 receptor availability (Volkow et al., 2001), and, because animal studies have demonstrated that dopamine levels influence duration perception, it is possible that chronic users of cocaine or methamphetamine may show impaired timing even after drug use has stopped.

{ The Psychologist | Continue reading }

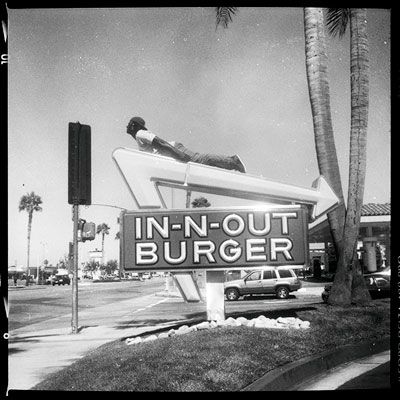

photo { Janine Gordon }

neurosciences, time | July 27th, 2012 3:18 pm

Arousal, the researchers contend, actually affects our perception of time. […]

The researchers presented 116 males with images from an online Victoria’s Secret catalog and gauged their response to receiving one of two fictitious Amazon.com promotions: a gift certificate available that day or one available three months from now. They asked the subjects the dollar value that would compensate for having to wait. Those exposed to sexually charged imagery (versus those in a control group exposed to nature images) were found to be more impatient and expressed that future discounts would have to be steeper to compensate for the time delay.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

painting { Willem Drost }

marketing, psychology, sex-oriented, time | July 27th, 2012 3:10 pm

The ability to be hypnotised seems to be a distinct trait that is distributed among the population, like height or shoe size, in a “bell curve” or normal distribution: a minority of people cannot engage with any suggestions, a minority can engage with almost all, and most people can achieve a few.

The key word here is “engage”, as, contrary to popular belief, hypnosis cannot be used to make people do something against their will, even though the effects seem to happen involuntarily. If this seems paradoxical, a good analogy is watching a movie: you don’t decide to react emotionally to the on-screen story, but you can choose to turn away or disengage at any time. In other words, the effects of the film, just like hypnosis, require your active participation.

{ Observer | Continue reading }

photo { Sam Margevicius }

neurosciences | July 26th, 2012 12:05 pm

Single-Nostril Navigational Reliance in Pigeons

We recorded the flight tracks of pigeons with previous homing experience equipped with a GPS data logger and released from an unfamiliar location with the right or the left nostril occluded. The analysis of the tracks revealed that the flight path of the birds with the right nostril occluded was more tortuous than that of unmanipulated controls. Moreover, the pigeons smelling with the left nostril interrupted their journey significantly more frequently and displayed more exploratory activity than the control birds, e.g. during flights around a stopover site.

[…]

How Randomly Selected Legislators Can Improve Parliament Efficiency

Democracies would be better off if they chose some of their politicians at random. That’s the word, mathematically obtained, from the Catanians’ extension of their random research, using insights they gleaned from the much earlier stupidity work by Cipolla.

Parliamentary voting behavior echoes, in a surprisingly detailed mathematical sense. Cipolla had sketched this in the “Basic Laws of Human Stupidity.” Cipolla gave an insulting, yet possibly accurate, description of any human group: “human beings fall into four basic categories: the helpless, the intelligent, the bandit, and the stupid.” Pluchino, Rapisarda, Garofalo and their colleagues base their mathematical model partly on this fourfold distinction.

{ Annals of Improbable Research | full issue }

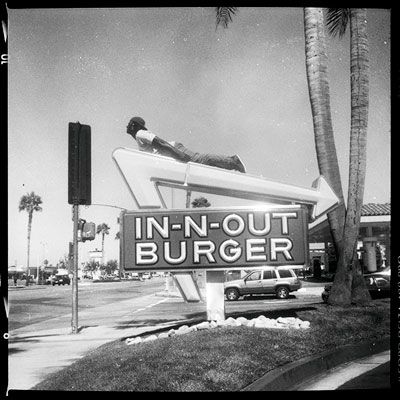

photo { Daniel Seung Lee }

birds, ideas, science | July 26th, 2012 9:48 am

Never before in human history have so many people been on the move […] airfare, new technologies […] space and time have never been so compressed. […] Migrants are no longer just ‘migrants’ but have become ‘transnationals’ maintaining links between their country of origin, their current country, and, not unusually, other countries where they have spent time.

The cool imagery of the new transnationalism is sometimes ruptured by analysts pointing out how class and race constrain or enable different forms of transnationalism. […] Qureshi starts with the observation that, according to the literature, Pakistanis in Britain have

developed a ‘transnational ethnic world’ that is continually reproduced through longdistance phone calls, frequent return visits and holidays, the consumption of circulating goods and media products, exchanges of gifts, philanthropic investments in schools, hospitals and humanitarian projects in Pakistan and so forth (Qureshi 2012, p. 2).

Descriptions of a British-Pakistani transnational world such as these are based on normalized assumptions of healthy, materially secure migrants whose first priority is their cultural and ethnic identity. The chronically ill men the researcher encountered in East London told a different story, a story where their ailing bodies tied them to London. […]

Their lack of financial resources has tied them to London and has made practices of transnationalism difficult: for instance, ‘cheap’ airfares are not ‘cheap’ to them but involve years of budgeting ahead and borrowing; their disability coupled with the fact that Pakistanis back home see them as ‘rich’ and expect bribes and presents at every turn, makes movement in Pakistan difficult and unpleasant for them; and, phone cards, the so-called ‘social glue’ of transnationalism, have to be carefully rationed.

{ Language on the move | Continue reading }

photo { Daniel Seung Lee }

science, within the world | July 25th, 2012 9:30 am

Does infinity exist?

This is a surprisingly ancient question. It was Aristotle who first introduced a clear distinction to help make sense of it. He distinguished between two varieties of infinity. One of them he called a potential infinity: this is the type of infinity that characterises an unending Universe or an unending list, for example the natural numbers 1,2,3,4,5,…, which go on forever. These are lists or expanses that have no end or boundary: you can never reach the end of all numbers by listing them, or the end of an unending universe by travelling in a spaceship. Aristotle was quite happy about these potential infinities, he recognised that they existed and they didn’t create any great scandal in his way of thinking about the Universe.

Aristotle distinguished potential infinities from what he called actual infinities. These would be something you could measure, something local, for example the density of a solid, or the brightness of a light, or the temperature of an object, becoming infinite at a particular place or time. You would be able to encounter this infinity locally in the Universe. Aristotle banned actual infinities: he said they couldn’t exist. This was bound up with his other belief, that there couldn’t be a perfect vacuum in nature. If there could, he believed you would be able to push and accelerate an object to infinite speed because it would encounter no resistance. […]

But in the world of mathematics things changed towards the end of the 19th century when the mathematician Georg Cantor developed a more subtle way of defining mathematical infinities. Cantor recognised that there was a smallest type of infinity: the unending list of natural numbers 1,2,3,4,5, … . He called this a countable infinity. […] This idea had some funny consequences. For example, the list of all even numbers is also a countable infinity. Intuitively you might think there are only half as many even numbers as natural numbers because that would be true for a finite list. But when the list becomes unending that is no longer true.

{ Plus | Continue reading | Other Plus articles on the subject of infinity }

photo { Thobias Fäldt }

ideas, mathematics | July 24th, 2012 5:07 pm

Every sect of Buddhism maintains that it is a religion of compassion and nonviolence. Throughout its history, however, Buddhism has occasionally been embroiled in warfare and military campaigns. Zen Buddhism in particular has managed to find its way into various military arts. From its incorporation into the Shaolin Monastery and the impact on the Japanese samurai to its absorption into the curriculum of several martial arts, Zen and fighting have come to be seen as closely related. This is due to certain characteristics of its doctrine as well as its practice. In fact, fighting is not entirely absent from Zen texts and literature. There are stories and kōans which depict amputations, encounters between samurai, or some kind of confrontation. Fighting, in the sense of an inner struggle is also present. […]

The objective of this examination is to draw parallels between Zen meditation and martial arts training and explore the reasons why Zen’s core philosophical doctrine and meditative practice can be integrated seamlessly into the martial arts.

{ SSRN | Continue reading }

fights, ideas, psychology | July 24th, 2012 5:00 pm

They found that people high in the psychological attribute called attachment anxiety (a tendency to worry about the proximity and availability of a romantic partner) responded to memories of a relationship breakup with an increased preference for warm-temperature foods over cooler ones: soup over crackers. Subjects low in attachment anxiety — those more temperamentally secure — did not show this “comfort food” effect. […]

The fact that individual differences in a relationship-oriented trait (attachment anxiety) are related to a person’s sensitivity to unconscious temperature-related cues speaks to the “under the hood” unconscious mingling that occurs between our social perceptual system and our temperature perception system. Though people predisposed to worry about their relationships seem to be more sensitive to these cues, we are all predisposed to the blurring of different types of experience. Similar recent experiments have demonstrated, for example, that briefly holding a warm beverage buoys subsequent ratings of another’s personality, that social isolation sensitizes a person to all things chilly, that inappropriate social mimicry creates a sense of cold, and that differences in the setting of the experimental lab’s thermostat leads test subjects to construe social relationships differently.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

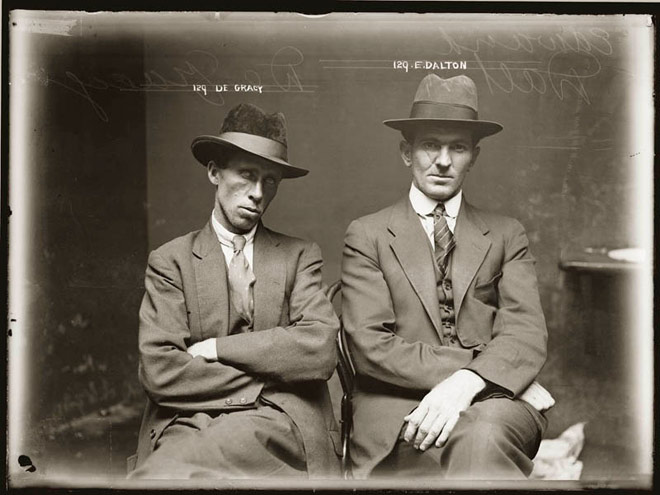

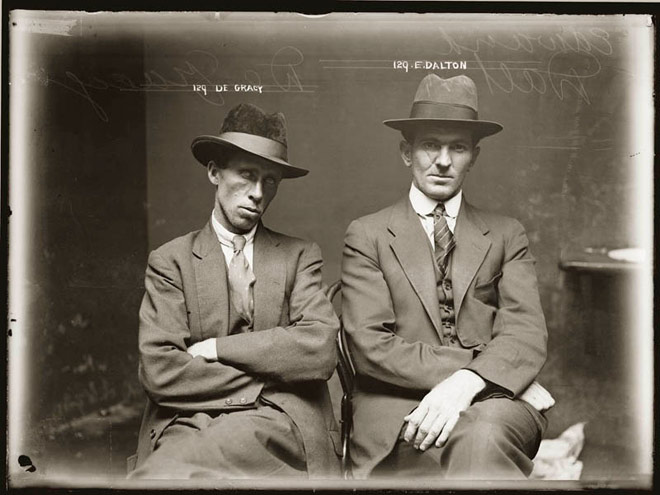

photo { The Sydney Justice & Police Museum | Mugshots from the 1920s }

psychology, temperature | July 24th, 2012 4:56 pm

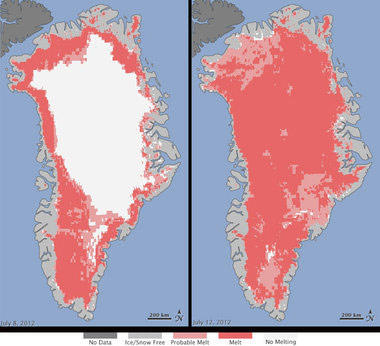

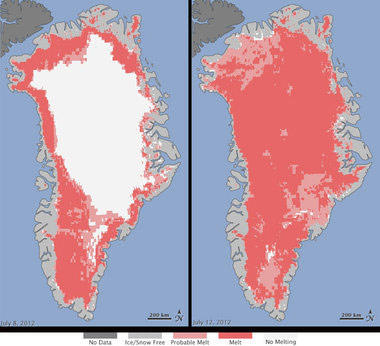

{ Three satellites found that 97 percent of Greenland — the land mass second only to Antarctica for its volume of ice — underwent a thaw never before seen in 33 years of satellite tracking, NASA reported Tuesday. Satellite experts at first didn’t trust their readings, especially since they showed an incredible acceleration. Over four days, Greenland’s ice sheet — which covers 683,000 square miles – went from 40 percent in thaw to nearly entirely in thaw. | NBC | Continue reading | Thanks Samantha }

climate, incidents, water | July 24th, 2012 4:14 pm

We experience the world serially rather than simultaneously. A century of research on human and nonhuman animals has suggested that the first experience in a series of two or more is cognitively privileged.

{ PLoS ONE | Continue reading }

It’s a long-standing truism. Plaintiffs have an edge with the jury because they go first. The defense has to convince those same jurors that the plaintiff story just isn’t true. […]

Researchers performed studies wherein they show that what we see first is what we most often prefer. Whether it was human salespeople, bubblegum, or which of two violent criminals was more worthy of parole–the photo we see first is the one we prefer to either purchase a vehicle from, chew, or deem more worthy of parole. Are we really that simple-minded? Unfortunately, it would appear the answer is yes.

But this tendency is only reliable when we are forced to make our decisions quickly. When we are given time to consider and ponder our choices–like juries have–we don’t tend to choose the first item brought to our attention, but rather the most recent.

{ Keene Trial | Continue reading }

photo { George W. Gardner }

law, psychology | July 23rd, 2012 12:49 pm

When you walk through the self-help aisle of any bookstore, you are likely to see plenty of books based on the notion that positive thinking is the key to getting what you want. The message is clear: if you want to achieve something, just keep telling yourself “I can!” and envision yourself accomplishing your goals. Success will surely come your way.

Not so, says years of psychological research. Certain kinds of positive thoughts, known in the research as fantasies, can actually be detrimental to performance.

{ Psych Your Mind | Continue reading }

psychology | July 23rd, 2012 12:36 pm

Bioengineers have made an artificial jellyfish using silicone and muscle cells from a rat’s heart. The synthetic creature, dubbed a medusoid, looks like a flower with eight petals. When placed in an electric field, it pulses and swims exactly like its living counterpart.

“Morphologically, we’ve built a jellyfish. Functionally, we’ve built a jellyfish. Genetically, this thing is a rat,” says Kit Parker, a biophysicist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who led the work.

{ Nature | Continue reading | NERS/Discover }

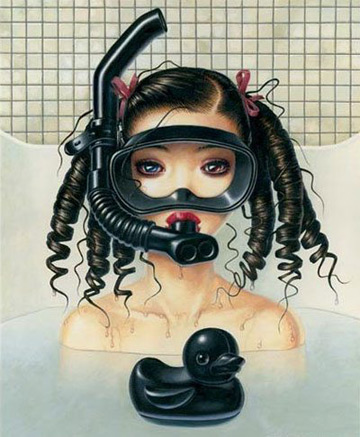

artwork { Trevor Brown }

jellyfish, science, technology | July 23rd, 2012 6:18 am

Smeesters published a different study in the Journal of Experimental Psychology suggesting that even manipulating colors such as blue and red can make us bend one way or another.

Except that apparently none of it is true. Last month, after being exposed by Uri Simonsohn at the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Smeesters acknowledged manipulating his data, an admission that been the subject of fervent discussions in the scientific community. Dr. Smeesters has resigned from his position and his university has asked that the respective papers be retracted from the journals. The whole affair might be written off as one unfortunate case, except that, as Smeesters himself pointed out in his defense in Discover Magazine, the academic atmosphere in the social sciences, and particularly in psychology, effectively encourages such data manipulation to produce “statistically significant” outcomes.

{ Time | Continue reading }

image { Vaka Valo, DRXXM DXXRY }

ideas, psychology | July 22nd, 2012 10:21 am

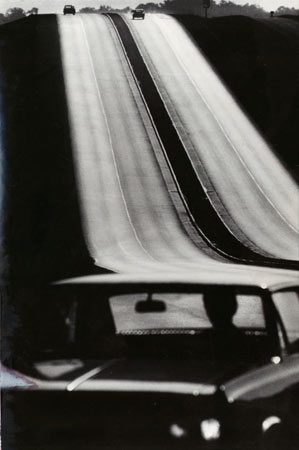

The researchers found that the effects that awe has on decision-making and well-being can be explained by awe’s ability to actually change our subjective experience of time by slowing it down. Experiences of awe help to brings us into the present moment which, in turn, adjusts our perception of time, influences our decisions, and makes life feel more satisfying than it would otherwise.

{ EurekArlert | Continue reading }

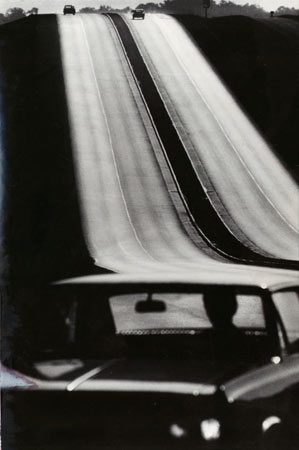

photo { Steven Siegel | more }

photogs, psychology | July 21st, 2012 4:48 am

Most people think that even though it is possible that they are dreaming right now, the probability of this is very small, perhaps as small as winning the lottery or being struck by lightning. In fact the probability is quite high. Let’s do the maths.

{ OUP | Continue reading }

image { Dr. Julius Neubronner’s Miniature Pigeon Camera }

birds, flashback, psychology, technology | July 21st, 2012 4:47 am

The human genome is estimated to contain about 23 000 genes. Where do these genes come from? Well, from your parents. And their parents. And so on. But, surely, if we go back far enough, there haven’t been 23 000 genes all along? However life originated, the first DNA carrying organisms probably had significantly fewer genes. So, where did all these new genes come from? How are genes born?

Well, there are two main ways:

• Re-organization of existing genes. […]

• All new. In other words, not based on previously present genes. This is what the new study investigates.

{ The Beast, the Bard and the Bot | Continue reading }

related { The genetics of stupidity }

photo { Paolo Ventura }

genes | July 21st, 2012 4:45 am

Advertisers bombard us relentlessly. Fortunately, our brains have an inbuilt BS-detector that shields us from the onslaught - a mental phenomenon that psychologists call simply “resistance.” Ads from dodgy companies, our own pre-existing preferences, and a forewarning of a marketing attack can all marshal greater psychological resistance within us.

However, a new study suggests that funny adverts lower our guard, leaving us vulnerable to aggressive marketing.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

marketing, psychology | July 19th, 2012 8:25 am

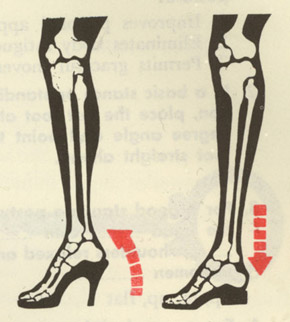

At some point in evolution, our ancestors switched from walking on all four limbs to just two, and this transition to bipedalism led to what is referred to as the obstetric dilemma. The switch involved a major reconfiguration of the birth canal, which became significantly narrower because of a change in the structure of the pelvis. At around the same time, however, the brain had begun to expand.

One adaptation that evolved to work around the problem was the emergence of openings in the skull called fontanelles. The anterior fontanelle enables the two frontal bones of the skull to slide past each other, much like the tectonic plates that make up the Earth’s crust. This compresses the head during birth, facilitating its passage through the birth canal.

In humans, the anterior fontanelle remains open for the first few years of life, allowing for the massive increase in brain size, which occurs largely during early life. The opening gets gradually smaller as new bone is laid down, and is completely closed by about two years of age, at which time the frontal bones have fused to form a structure called the metopic suture. In chimpanzees and bononbos, by contrast, brain growth occurs mostly in the womb, and the anterior fontanelle is closed at around the time of birth.

{ Neurophilosophy/Guardian | Continue reading }

image { Lola Dupré }

brain, flashback, kids, science | July 18th, 2012 2:29 pm

Humans increase their body weight by a factor of 30 or so as they grow from babies to adults. For elephants the factor is closer to 100.

But this raises a problem for biologists. They know that internal organs all grow at almost exactly the same rate, a phenomenon known as proportionate growth. But how does the body organise this?

At one level, the answer is clear. The growth is controlled by chemical regulators–hormones, promoters, inhibitors and so on. These in turn are controlled by various genes.

But this isn’t an entirely satisfactory explanation. The reaction rates associated with these chemicals can vary hugely from cell to cell because only a relatively small number of molecules are involved.

If these variations were independent, they would cause much greater variation in growth throughout the body than is observed. So some other organising principle must be at work.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

photo { David LaChapelle for Harvey Nichols, 1998 | Agency: Harari Page }

science | July 18th, 2012 1:45 pm

One definition is that a Type III error occurs when you get the right answer to the wrong question. This is sometimes called a Type 0 error.

{ Graph Pad | Continue reading }

photos { Stephen Shore, American Surfaces, 1972 }

Linguistics, mathematics, photogs | July 17th, 2012 9:37 am