birds

There are 290 species of pigeon in the world, but only one has adapted to live in cities. Feral pigeons are synanthropes: they thrive in human environments where they can skim a living off our excess, nesting in the nooks and crannies of tall buildings that mimic the cliff faces on which their genetic ancestors – Columba livia, the rock dove – once lived. We think of pigeons as grey but they are composed of an oceanic palette: deep blues and greens flecked with white, like the crest of a wave. […]

In the 1970s and 1980s, the US Coastguard trained pigeons to recognise people lost at sea as part of Project Sea Hunt. The birds were placed in observation bubbles mounted on the bottom of helicopters and trained to peck at buttons when they spotted a scrap of coloured fabric floating in the sea. Pigeons were able to find the fabric 93 per cent of the time. Human subjects managed the same task 38 per cent of the time.

Pigeons are more intelligent than we give them credit for, one of the few animals – along with great apes, dolphins and elephants – able to pass the mirror self-recognition test. If you mark a pigeon’s wing and let it look in a mirror it will try to remove the mark, realising that what it sees is a reflected image of its own body. Pigeons can recognise video footage of themselves shown with a five-second delay (three-year-old children find it difficult to comprehend a two-second delay). They are able to recognise individuals from photographs, and a neuroscientist at Keio University in Japan has trained them to distinguish between the paintings of Matisse and Picasso. […]

The first experimental pigeon drops of Operation Columba took place at the end of 1940, and from early 1941 until September 1944 the service dropped 16,000 pigeons on small parachutes over occupied Europe, in an arc running from Copenhagen to Bordeaux. Attached to the pigeons was a questionnaire asking whoever found them to provide intelligence – on troop movements, the position of guns or radar arrays and ‘the extent to which people could hear BBC radio clearly and their views of the service it provided’ – by return of pigeon. […] Over the course of the war the Germans became, as MI6 put it, ‘pigeon minded’. Rewards were offered for pigeons turned in, and booby-trapped birds were placed in fields to injure anyone who might be tempted to send information back to Britain. […] he British, too, were worried that German spies were using birds to communicate, and a team of British falconers was established to try to intercept them, but they only managed to catch friendly birds, probably because, despite the hysteria, there were no German pigeons in Britain.

{ London Review of Books | Continue reading }

photo { Bridget Riley, Untitled (Winged Curve), 1966 }

birds | April 10th, 2019 9:25 am

In a mossy forest in the western Andes of Ecuador, a small, cocoa-brown bird with a red crown sings from a slim perch. […] Three rival birds call back in rapid response. […] They are singing with their wings, and their potential mates seem to find the sound very alluring. […]

This is an evolutionary innovation — a whole new way to sing. But the evolutionary mechanism behind this novelty is not adaptation by natural selection, in which only those who survive pass on their genes, allowing the species to become better adapted to its environment over time. Rather, it is sexual selection by mate choice, in which individuals pass on their genes only if they’re chosen as mates. From the peacock’s tail to the haunting melodies of the wood thrush, mate choice is responsible for much of the beauty in the natural world.

Most biologists believe that these mechanisms always work in concert — that sex appeal is the sign of an objectively better mate, one with better genes or in better condition. But the wing songs of the club-winged manakin provide new insights that contradict this conventional wisdom. Instead of ensuring that organisms are on an inexorable path to self-improvement, mate choice can drive a species into what I call maladaptive decadence — a decline in survival and fecundity of the entire species. It may even lead to extinction.

{ NYT | Continue reading }

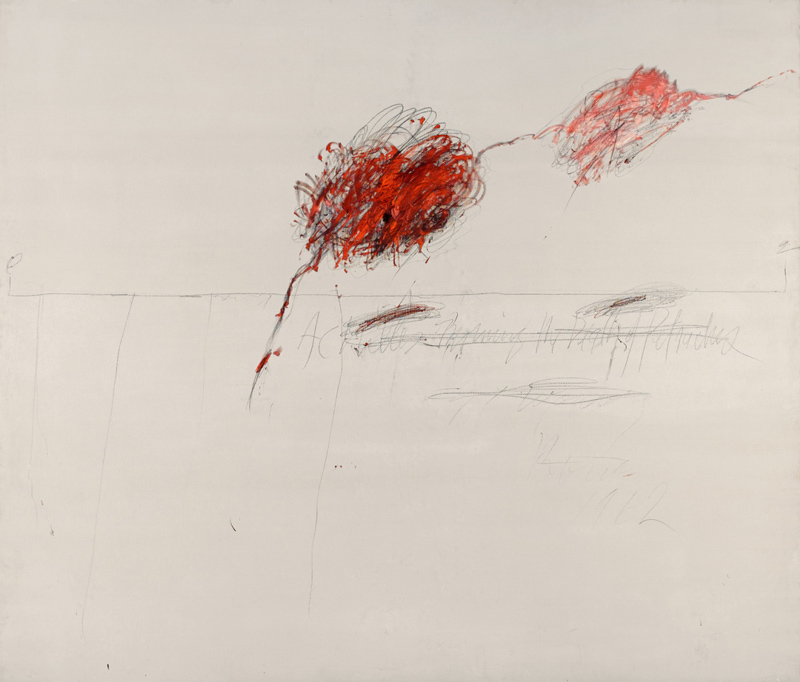

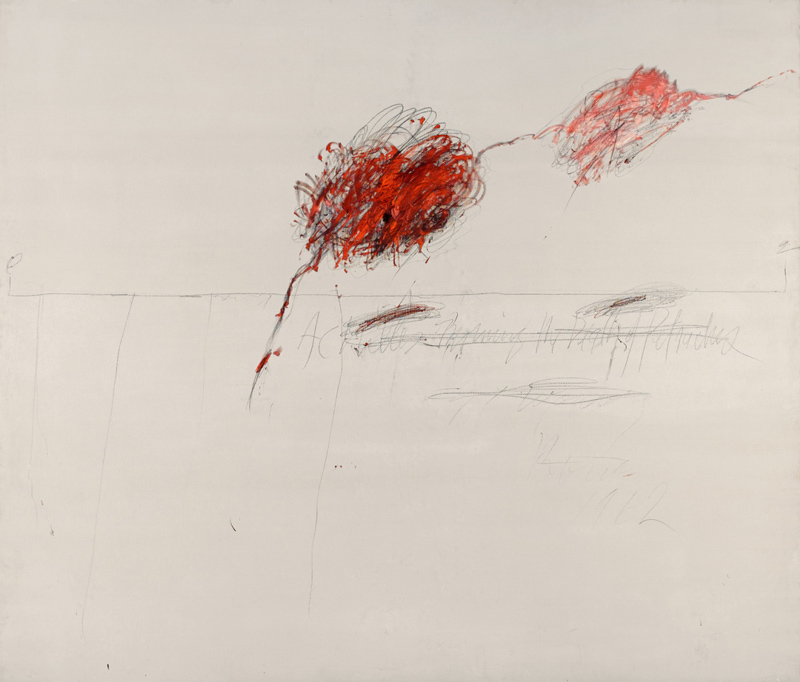

art { Cy Twombly, Achilles Mourning the Death of Patroclus, 1962 }

birds, evolution, science | May 13th, 2017 10:43 am

Raising chickens in backyard coops is all the rage with nostalgia-loving hipsters but apparently the facial hair obsessed faux farmers often don’t realize that raising hens is loud, labor intensive work because animal shelters are now inundated with hundreds of unwanted urban fowl.

From California to New York, animal shelters are having a hard time coping with the hundreds of chickens being dropped off, sometimes dozens at a time, by bleary-eyed pet owners who might not have realized that chickens lay eggs for only two years but live for a decade or more. […]

The problem with urban farmed chickens starts at birth when hipsters purchase chicks from the same hatcheries that supply large commercial poultry producers. However, the commercial chickens are specifically bread to produce as many eggs as possible in the shortest amount of time.

{ NY Post | Continue reading }

birds, haha | July 10th, 2013 8:34 am

birds, cuties | June 30th, 2013 8:21 am

On 5 June 1995 an adult male mallard collided with the glass façade of the Natuurmuseum Rotterdam and died. An other drake mallard raped the corpse almost continuously for 75 minutes. Then the author [of this paper] disturbed the scene and secured the dead duck. Dissection showed that the rape-victim indeed was of the male sex. It is concluded that the mallards were engaged in an ‘Attempted Rape Flight’ that resulted in the first described case of homosexual necrophilia in the mallard.

{ C.W. Moeliker | PDF }

birds, horror, science | February 25th, 2013 10:55 am

Single-Nostril Navigational Reliance in Pigeons

We recorded the flight tracks of pigeons with previous homing experience equipped with a GPS data logger and released from an unfamiliar location with the right or the left nostril occluded. The analysis of the tracks revealed that the flight path of the birds with the right nostril occluded was more tortuous than that of unmanipulated controls. Moreover, the pigeons smelling with the left nostril interrupted their journey significantly more frequently and displayed more exploratory activity than the control birds, e.g. during flights around a stopover site.

[…]

How Randomly Selected Legislators Can Improve Parliament Efficiency

Democracies would be better off if they chose some of their politicians at random. That’s the word, mathematically obtained, from the Catanians’ extension of their random research, using insights they gleaned from the much earlier stupidity work by Cipolla.

Parliamentary voting behavior echoes, in a surprisingly detailed mathematical sense. Cipolla had sketched this in the “Basic Laws of Human Stupidity.” Cipolla gave an insulting, yet possibly accurate, description of any human group: “human beings fall into four basic categories: the helpless, the intelligent, the bandit, and the stupid.” Pluchino, Rapisarda, Garofalo and their colleagues base their mathematical model partly on this fourfold distinction.

{ Annals of Improbable Research | full issue }

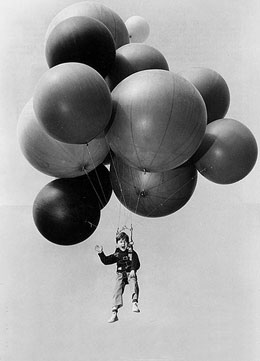

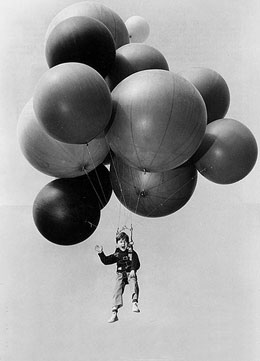

photo { Daniel Seung Lee }

birds, ideas, science | July 26th, 2012 9:48 am

Most people think that even though it is possible that they are dreaming right now, the probability of this is very small, perhaps as small as winning the lottery or being struck by lightning. In fact the probability is quite high. Let’s do the maths.

{ OUP | Continue reading }

image { Dr. Julius Neubronner’s Miniature Pigeon Camera }

birds, flashback, psychology, technology | July 21st, 2012 4:47 am

The extraordinary ability of birds and bats to fly at speed through cluttered environments such as forests has long fascinated humans. It raises an obvious question: how do these creatures do it?

Clearly they must recognise obstacles and exercise the necessary fine control over their movements to avoid collisions while still pursuing their goal. And they must do this at extraordinary speed.

From a conventional command and control point of view, this is a hard task. Object recognition and distance judgement are both hard problems and route planning even tougher.

Even with the vast computing resources that humans have access to, it’s not at all obvious how to tackle this problem. So how flying animals manage it with immobile eyes, fixed focus optics and much more limited data processing is something of a puzzle.

Today, Ken Sebesta and John Baillieul at Boston University reveal how they’ve cracked it. These guys say that flying animals use a relatively simple algorithm to steer through clutter and that this has allowed them to derive a fundamental law that determines the limits of agile flight.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

birds, science, technology | March 16th, 2012 3:22 pm

Why do birds sing in the morning?

There are two parts to the question, of course: why do birds sing? And why do they sing in the morning more than at other times of day? The first I think we’ve had a pretty good idea about for a long time, and there are two main reasons: to attract mates, and to claim their territory. (…)

One of the oldest ideas is that they sing in the morning because it’s still too dark to be out and about finding food, so you might as well sing. That’s a pretty solid idea - but it doesn’t really explain why they sing more in the morning than in the evening, when the light also fades - or even in the middle of the night. Another theory is that the conditions early in the morning - often cool and with lower humidity than later in the day - might be particularly good for letting the sounds of the song carry further, though recent experiments suggest that actually the middle of the day might be the best time to sing if acoustic conditions are what’s important so I don’t think that’s a winning idea. The third and most interesting theory is that birds sing most in the morning because that’s when, most days, they’ve got spare energy to use up. (…)

Here in Africa there’s an additional complication we should consider: many female birds sing too.

{ Safari Ecology | Continue reading }

birds | March 12th, 2012 2:51 pm

Whenever we are doing something, one of our brain hemispheres is more active than the other one. However, some tasks are only solvable with both sides working together.

PD Dr. Martina Manns and Juliane Römling of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum are investigating, how such specializations and co-operations arise. Based on a pigeon-model, they are proving for the first time in an experimental way, that the ability to combine complex impressions from both hemispheres, depends on environmental factors in the embryonic stage. (…)

First the pigeons have to learn to discriminate the combinations A/B and B/C with one eye, and C/D and D/E with the other one. Afterwards, they can use both eyes to decide between, for example, the colours B/D. However, only birds with embryonic light experience are able to solve this problem.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

Imagine the smell of an orange. Have you got it? Are you also picturing the orange, even though I didn’t ask you to? Try fish. Or mown grass. You’ll find it’s difficult to bring a scent to mind without also calling up an image. It’s no coincidence, scientists say: Your brain’s visual processing center is doing double duty in the smell department.

{ Inkfish | Continue reading }

birds, brain, eyes, olfaction | March 5th, 2012 1:20 pm

Even though chili fruits are popular amongst humans for being hot, they didn’t evolve this character to keep foodies and so-called “chili-heads” happy. Previous research indicates that chilis, Capsicum spp., evolved their characteristic “heat” or pungency as a chemical defence to protect their fruits from fungal infections and from being eaten by herbivores. Chili pungency is created by capsaicinoids, a group of molecules that are produced by the plant and sequestered in its fruits. Capsaicinoids trigger that familiar burning sensation by interacting with a receptor located in pain- and heat-sensing neurons in mammals (including humans).

In contrast, birds lack this specific receptor protein, so their pain- and heat-sensing neurons remain undisturbed by capsaicinoids, which is the reason they eat chili fruits with impunity. Additionally, because birds lack teeth, they don’t damage chili seeds, which pass unharmed through their digestive tracts. For these reasons, wild chili fruits are bright red, a colour that attracts birds, so the plants effectively employ birds to disperse their seeds far and wide.

{ The Guardian | Continue reading }

birds, food, drinks, restaurants, science | December 23rd, 2011 11:27 am

{ 1 | 2 }

birds, halves-pairs, visual design | August 1st, 2011 4:35 pm

{ A black-headed female Gouldian finch, Erythrura gouldiae, chooses her mate. Having a genetically incompatible mate can increase a female bird’s stress hormone levels which then can affect the sex ratio of her offspring. | Nature | Continue reading }

related { Effects of stress can be inherited, and here’s how }

birds, relationships, science | June 28th, 2011 1:16 pm

birds, relationships, video | May 31st, 2011 2:33 pm

A study found that pigeons recognize a human face’s identity and emotional expression in much the same way as people do.

Pigeons were shown photographs of human faces that varied in the identity of the face, as well as in their emotional expression — such as a frown or a smile. In one experiment, pigeons, like humans, were found to perceive the similarity among faces sharing identity and emotion. In a second, key experiment, the pigeons’ task was to categorize the photographs according to only one of these dimensions and to ignore the other. The pigeons found it easier to ignore emotion when they recognized face identity than to ignore identity when they recognized face emotion.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

images { 1 | 2. Shomei Tomatsu }

birds, science | April 11th, 2011 8:51 pm

The secret behind the beautiful songs that birds sing has been decoded and reproduced for the first time.

One of the great challenges in neuroscience is to explain how collections of neural circuits produce the complex sequences of signals that result in behaviours such as animal communication, birdsong and human speech.

Among the best studied models in this area are birds such as zebra finches. These enthusiastic singers produce songs that consist of long but relatively simple sequences of syllables. These sequences have been well studied and their statistical properties calculated.

It turns out that these statistical properties can be accurately reproduced using a type of simulation called a Markov model in which each syllable is thought of as a state of the system and whose appearance in a song depends only on the statistical properties of the previous syllable. (…)

But other birds produce more complex songs and these are harder to explain. One of these is the Bengalese finch whose songs vary in seemingly unpredictable ways and cannot be explained a simple Markov model. Just how the Bengalese finch generates its song is a mystery.

Until now. (…) Instead of the simple one-to-one mapping between syllable and circuit that explains zebra finch song, they say that in Bengalese finches there is a many-to-one mapping, meaning that a given syllable can be produced by several neural circuits. That’s why the statistics are so much more complex, they say.

This type of model is called a hidden Markov model because the things that drives the observable part of the system–the song–remains hidden.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

related { New research suggests that our brains have a built-in bias against people whose accents don’t sound like our own }

birds, music, neurosciences, science | November 17th, 2010 6:33 pm