Pause, flash

{ A new look at traffic lights | more | via copyranter | Related: Control Safety Traffic Light Concept }

{ A new look at traffic lights | more | via copyranter | Related: Control Safety Traffic Light Concept }

Social cognition is the scientific study of the cognitive events underlying social thought and attitudes. Currently, the field’s prevailing theoretical perspectives are the traditional schema view and embodied cognition theories. Despite important differences, these perspectives share the seemingly uncontroversial notion that people interpret and evaluate a given social stimulus using knowledge about similar stimuli. However, research in cognitive linguistics (e.g., Lakoff & Johnson, 1980) suggests that people construe the world in large part through conceptual metaphors, which enable them to understand abstract concepts using knowledge of superficially dissimilar, typically more concrete concepts.

{ Psychological Bulletin | Continue reading }

In general structure, Kant’s model of the mind was the dominant model in the empirical psychology that flowed from his work and then again, after a hiatus during which behaviourism reigned supreme (roughly 1910 to 1965), toward the end of the 20th century, especially in cognitive science.

Three ideas define the basic shape (‘cognitive architecture’) of Kant’s model and one its dominant method. They have all become part of the foundation of cognitive science.

• The mind is complex set of abilities (functions). (As Meerbote 1989 and many others have observed, Kant held a functionalist view of the mind almost 200 years before functionalism was officially articulated in the 1960s by Hilary Putnam and others.)

• The functions crucial for mental, knowledge-generating activity are spatio-temporal processing of, and application of concepts to, sensory inputs. Cognition requires concepts as well as percepts.

• These functions are forms of what Kant called synthesis. Synthesis (and the unity in consciousness required for synthesis) are central to cognition.

These three ideas are fundamental to most thinking about cognition now. Kant’s most important method, the transcendental method, is also at the heart of contemporary cognitive science.

• To study the mind, infer the conditions necessary for experience. Arguments having this structure are called transcendental arguments.

photo { John Zimmerman }

Older people may have always existed throughout history, but they were rare. Aging as we know it, and the diseases and disorders that accompany it, represent new phenomena—products of 20th century resourcefulness. When infectious diseases were largely vanquished in the developed world, few anticipated the extent to which chronic degenerative diseases would rise. We call them heart disease, cancer, stroke, arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, and many more, but we might as well collectively use one word to describe them all—aging.

Aging may be defined as the accumulation of random damage to the building blocks of life—especially to DNA, certain proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids (fats)—that begins early in life and eventually exceeds the body’s self-repair capabilities. This damage gradually impairs the functioning of cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems, thereby increasing vulnerability to disease and giving rise to the characteristic manifestations of aging, such as loss of muscle and bone mass, decline in reaction time, compromised hearing and vision, and reduced elasticity of the skin. (…)

Humanity is paying a heavy price for the privilege of living extended lives—a new and much more complicated relationship with disease.

related { Some animals live for 400 years. What can they teach us about extending life? }

photo { Misha De Ridder }

Conversations on news sites show how information and ideas spread.

There’s a science behind the comments on websites. It’s actually quite predictable how much chatter a post on Slashdot or Wikipedia will attract, according to a new study of several websites with large user bases. (…)

The findings give hope to social scientists trying to understand broader phenomena, like how rumors about a candidate spread during a campaign or how information about street protests flows out of a country with state-controlled media.

photo { Michael Casker }

In 1961 a new edition of an old and esteemed dictionary was released. The publisher courted publicity, noting the great expense ($3.5 million) and amount of work (757 editor years) that went into its making. But the book was ill-received. It was judged “subversive” and denounced in the New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, the Atlantic, the New Yorker, Life, and dozens of other newspapers, magazines, and professional journals. Not every publication condemned the volume, but the various exceptions did little to change the widespread impression of a well-known reference work being cast out from the better precincts of American culture.

The dictionary was called “permissive” and details of its perfidy were aired, mocked, and distorted until the publisher was put on notice that it might be bought out to prevent further circulation of this insidious thirteen-and-a-half–pound, four-inch–thick doorstop of a book.

Webster’s Third New International (Unabridged) wasn’t just any dictionary, of course, but the most up-to-date and complete offering from America’s oldest and most respected name in lexicography. (So respected, in fact, that for more than a hundred years other publishers have adopted the Webster’s name as their own.)

The dictionary’s previous edition, Webster’s New International Second Edition (Unabridged), was the great American dictionary with 600,000 entries and numerous competitors but no rivals. With a six-inch-wide binding, it weighed four pounds more than Webster’s Third (W3) and possessed an almost unanswerable air of authority. If you wanted to know how to pronounce chaise longue, it told you, shāz long, end of discussion. It did not stoop to correct or even mention the vulgarization that sounds like “Che’s lounge.” When to use less and when to use fewer? It indicated what strict usage prescribed. It defined celebrant as “one who celebrates a public religious rite; esp. the officiating priest,” not just any old party guest.

The third edition took a more empirical approach, listing variations in pronunciation and spelling until the reader looking for the one correct answer became the recipient of numerous competing answers: shāz long and Che’s lounge (with lounge labeled a folk etymology). Shades of meaning were differentiated with scads of quotations from the heights of literature and the lows of yesterday’s news section. The new unabridged dictionary was more rigorous but harder to use. And all this made some people quite irate. (…)

“I am not a linguist and have no claim to being a lexicographer but have done considerable research on 17th and 18th century dictionaries,” wrote Philip Gove in a job inquiry to the G. & C. Merriam Company in 1946. Gove was a lieutenant commander in the Navy on leave from a teaching position at New York University and, with the end of the war, about to be discharged. A literature PhD who had published articles on Samuel Johnson’s pioneering dictionary, he soon became an assistant editor at Merriam. Five years later, after a long search for a prominent editor to oversee the editing and production of W3, the company promoted the painstaking Gove, then in his late forties, to the position. (…)

An entry’s main function, by Gove’s lights, was to report the existence of a word and define its meanings according to common usage. (…) But how a word should appear in writing was not uppermost in the minds responsible for W3. The only actual word given a capital letter in the first printing was God. Others given a capital letter in later printings were copyrighted names such as Kleenex, which appeared as kleenex in the first printing (the reason it was in the dictionary, of course, was that it had changed in usage from denoting a brand of tissue to being a synonym for tissue), but was thereafter capitalized under threat of lawsuit.

Another innovation Gove introduced was in the style of definition-writing. “He insisted,” explained Morton “that essential information be logically organized in a single coherent and clearly expressed phrase.” In some cases, this led to a more direct expression of a word’s meaning, but it also led to infelicities. The prose was made even more curious by Gove’s hostility to commas, which he banned from definition-writing except to separate items in a series. He even claimed to have saved the equivalent of eighty pages of text by reducing comma use.

The circuitous entry for door, quoted in a caustic Washington Post article, became well known: “a movable piece of a firm material or a structure supported usu. along one side and swinging on pivots or hinges, sliding along a groove, rolling up and down, revolving as one of four leaves, or folding like an accordion by means of which an opening may be closed or kept open . . .” and so on.

This definition, said Gove, was for someone who had never seen a door. (…)

In a 1961 article he penned for Word Study, a marketing newsletter that Merriam circulated to educators, Gove discussed how the young science of linguistics was altering the teaching of grammar. (…) The major point of Gove’s article was to note that many precepts of linguistics, some of which had long been commonplace in lexicography, increasingly underlay the teaching of grammar. The National Council of Teachers of English had even endorsed five of them, and Gove quoted the list, which originally came from the 1952 volume English Language Arts:

1—Language changes constantly.

2—Change is normal.

3—Spoken language is the language.

4—Correctness rests upon usage.

5—All usage is relative.These precepts were not new, he added, “but they still come up against the attitude of several generations of American educators who have labored devotedly to teach that there is only one standard which is correct.”

photo { Alec Soth }

…an important question in philosophy, the problem of presuppositions.

An example is Descartes’ celebrated phrase at the beginning of the Discourse on the Method:

Good sense is the most evenly shared thing in the world . . the capacity to judge correctly and to distinguish the true from the false, which is properly what one calls common sense or reason, is naturally equal in all men…

For Descartes, thought has a natural orientation towards truth, just as for Plato, the intellect is naturally drawn towards reason and recollects the true nature of that which exists. This, for Deleuze, is an image of thought.

Although images of thought take the common form of an ‘Everybody knows…’, they are not essentially conscious. Rather, they operate on the level of the social and the unconscious, and function, “all the more effectively in silence.”

photo { Jeff Luker }

Everyone knows someone who likes to listen to some music while they work. Maybe it’s one of your kids, listening to the radio while they try to slog through their homework. (…)

It’s a widely held popular belief that listening to music while working can serve as a concentration aid, and if you walk into a public library or a café these days it’s hard not to notice a sea of white ear-buds and other headphones. Some find the music relaxing, others energizing, while others simply find it pleasurable. But does listening to music while working really improve focus? It seems like a counterintuitive belief – we know that the brain has inherently limited cognitive resources, including attentional capacity, and it seems natural that trying to perform two tasks simultaneously would cause decreased performance on both.

The currently existing body of research thus far has yielded contradictory results. Though the results of most empirical studies suggest that music often serves more as a distraction than a study aid, a sizable minority have displayed some instances in which music seems to have improved performance on some tasks.

artwork { Il Lee }

In “What Technology Wants,” Kelly provides an engaging journey through the history of “the technium,” a term he uses to describe the “global, massively interconnected system of technology vibrating around us,” extending “beyond shiny hardware to include culture, art, social institutions and intellectual creations of all types.”

We learn, for instance, that our hunter-gatherer ancestors, despite their technological limitations, may have worked as little as three to four hours a day.

Since then, the technium has grown exponentially: while colonial American households boasted fewer than 100 objects, Kelly’s own home contains, by his reckoning, more than 10,000. As Kelly is a gadget-phile by trade, this index probably inflates the current predominance of technology and its products, but a thoroughly mundane statistic makes the same point: a typical supermarket now offers more than 48,000 different items.

Kelly argues convincingly that this expansion of technology is beneficial. Technology creates choice and therefore enhances our potential for self-realization. No longer tied to the land, we can become, in principle, what we want to become. (…)

Kelly’s exploration of the factors underlying these trends, however, is more controversial. He sees evolution — both biological and technological — as an inexorable and predictable process; if life were to begin again on Earth, he argues, we’d see not only the re-evolution of humans, but humans who would invent pretty much the same stuff. To support his claims, Kelly describes parallel inventions on different isolated continents (the blowgun and the abacus, for example), and the presence of near-simultaneous inventions in modern times (the light bulb was invented at least two dozen times).

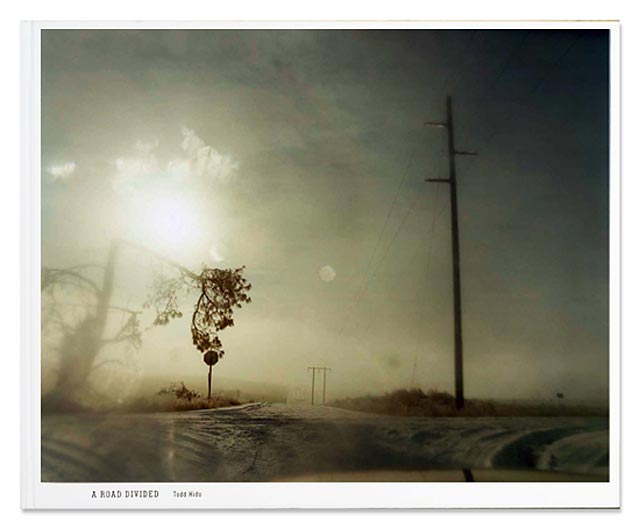

I believe that all those signs from your past and all those feelings and memories certainly come together, often subconsciously, and form some kind of a fragmented narrative. Often you’re telling your own story but you may not even know it. (…)

Larry Sultan truly was one of the most remarkable people that I have ever known. I was so fortunate to have been able to study under him and also become his friend and colleague. He was so incredibly articulate about talking about pictures and I learned so much from him about what photography can do and how it can mean something that extends way beyond what you are picturing in your images.

{ Interview with Todd Hido | Continue reading | Photo: Todd Hido }

Let’s start with the invention of air conditioning. This is only one of approximately a zillion topics addressed by the science writer Steven Johnson during the course of lunch at an Italian restaurant in downtown Manhattan; some of the others include Darwinian evolution, the creation of YouTube, the curiously perfect population density of the Park Slope neighbourhood of Brooklyn, the French Revolution, the London cholera epidemic of 1854, the first computer, The Wire, and why 9/11 wasn’t prevented.

But air conditioning provides a useful way to introduce Johnson’s current overarching obsession – the mysterious question of where good ideas come from – because it encapsulates how we generally like to think about inventors and inventions. One night in 1902, an ambitious young American engineer named Willis Carrier was waiting for a train, watching fog roll in across the platform, when he had a sudden flash of insight: he could exploit the principle of fog to cool buildings. He patented the idea, protected it fiercely, put his new invention into production, and made a fortune. In 2007, the still-surviving Carrier Corporation generated sales worth $15bn.

For Johnson, though, what’s really interesting about that story is how unusual it is: although the eureka moment is such a cliche, big new ideas almost never get born like that. “It’s weird, but innovation is one of those cases where the defining image, all the rhetoric and all the assumptions about how it happens, turn out to be completely backward. It’s very, very rare to find cases where somebody on their own, working alone, in a moment of sudden clarity has a great breakthrough that changes the world. And yet there seems to be this bizarre desire to tell the story that way.”

photo { Chris Brennan }

If the world is going to hell, why are humans doing so well?

For decades, apocalyptic environmentalists (and others) have warned of humanity’s imminent doom, largely as a result of our unsustainable use of and impact upon the natural systems of the planet. After all, the most recent comprehensive assessment of so-called ecosystem services—benefits provided for free by the natural world, such as clean water and air—found that 60 percent of them are declining.

Yet, at the exact same time, humanity has never been better. Our numbers continue to swell, life expectancy is on the rise, child mortality is declining, and the rising tide of economic growth is lifting most boats.

So which is it? Are these the best of times or the worst of times? Or both? And how imminent is our doom really? In the September issue of BioScience, a group of scientists attempts to reconcile the conflict and answer the question: “How is it that human well-being continues to improve as ecosystem services decline?”

Einstein presented what is referred to as the “block universe” – the notion that all times exist equally. So, what you see just depends on what you set t to in any given equation. “The distinction between past, present and future is only an illusion, however persistent,” the genius of relativity mused. He was so clear about the illusory nature of time that the thought even provided him with comfort in the face of death.

But the block universe, and the notion of God’s timelessness, have been challenged by scientists who also work on the relationship between science and religion. I’m thinking here of two physicists who are also well known as theologians, John Polkinghorne and Ian Barbour. Their questioning of the classical idea of God’s timeless nature presents an enormous challenge to received ideas about God. Interestingly, it’s a challenge that stems from both scientific and theological concerns. (…)

Scientifically, time is an oddity. Relativity theory treats it as one dimension of reality. Time is tantamount to the movement of mass in spacetime. So, time reversal, or retrocausality, has been proposed as a way to interpret antimatter — a positron being an electron that’s traveling backwards in time. Also, at a theoretical level, the equations that govern electromagnetic radiation don’t distinguish between time going forwards or backwards. And yet, in the macro-world of the everyday, we clearly can’t move temporally backwards, but only forwards. So how can this existential difference be reconciled?

Why war? Darwinian explanations, such as the popular “demonic males” theory of Harvard anthropologist Richard Wrangham, are clearly insufficient. They can’t explain why war emerged relatively recently in human prehistory—less than 15,000 years ago, according to the archaeological record—or why since then it has erupted only in certain times and places.

Many scholars solve this problem by combining Darwin with gloomy old Thomas Malthus. “No matter where we happen to live on Earth, we eventually outstrip the environment,” the Harvard archaeologist Steven LeBlanc asserts. “This has always led to competition as a means of survival, and warfare has been the inevitable consequence of our ecological-demographic propensities.” Note the words “always” and “inevitable.”

LeBlanc is as wrong as Wrangham. Analyses of more than 300 societies in the Human Relations Area Files, an ethnographic database at Yale University, have turned up no clear-cut correlations between warfare and chronic resource scarcity. (…)

War is both underdetermined and overdetermined. That is, many conditions are sufficient for war to occur, but none are necessary. Some societies remain peaceful even when significant risk factors are present, such as high population density, resource scarcity, and economic and ethnic divisions between people. Conversely, other societies fight in the absence of these conditions. What theory can account for this complex pattern of social behavior?

The best answer I’ve found comes from Margaret Mead, who as I mentioned in a recent post is often disparaged by genophilic researchers such as Wrangham. Mead proposed her theory of war in her 1940 essay “Warfare Is Only an Invention—Not a Biological Necessity.” She dismissed the notion that war is the inevitable consequence of our “basic, competitive, aggressive, warring human nature.” This theory is contradicted, she noted, by the simple fact that not all societies wage war. War has never been observed among a Himalayan people called the Lepchas or among the Eskimos. In fact, neither of these groups, when questioned by early ethnographers, was even aware of the concept of war. (…)

Warfare is “an invention,” Mead concluded, like cooking, marriage, writing, burial of the dead or trial by jury. Once a society becomes exposed to the “idea” of war, it “will sometimes go to war” under certain circumstances.

I like, I don’t like.

I like: salad, cinnamon, cheese, pimento, marzipan, the smell of new-cut hay, roses, peonies, lavender, champagne, loosely held political convictions, Glenn Gould, beer excessively cold, flat pillows, toasted bread, Havana cigars, Handel, measured walks, pears, white or vine peaches, cherries, colors, watches, pens, ink pens, entremets, coarse salt, realistic novels, piano, coffee, Pollock, Twombly, all romantic music, Sartre, Brecht, Jules Verne, Fourier, Eisenstein, trains, Médoc, having change, Bouvard et Pécuchet, walking in the evening in sandals on the lanes of South-West, the Marx Brothers, the Serrano at seven in the morning leaving Salamanca, et cetera.

I don’t like: white Pomeranians, women in trousers, geraniums, strawberries, harpsichord, Miró, tautologies, animated cartoons, Arthur Rubinstein, villas, afternoons, Satie, Vivaldi, telephoning, children’s choruses, Chopin concertos, Renaissance dances, pipe organ, Marc-Antoine Charpentier, his trumpets and his kettledrums, the politico-sexual, scenes, initiatives, fidelity, spontaneity, evenings with people I don’t know, et cetera.

I like, I don’t like: this is of no importance to anyone; this, apparently, has no meaning. And yet all this means: my body is not the same as yours.

{ Roland Barthes, Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes, 1975 }

…an essential difference between genetics, the study of a fixed inheritance in DNA, and epigenetics, which is the study of how the environment affects those genes, causing different ones to be active at different rates, times and places in the body.

Evolutionary approaches to human behavior have often been framed in terms of “good” and “bad”: Why did homosexuality evolve if it’s “bad” for the genes, because it reduces the chance that they’ll be passed on to a new generation? Why wouldn’t an impulsive temperament be “selected against,” seeing as its possessors would be more likely to fall off cliffs? Some thinkers have twisted themselves into pretzels trying to explain why a “maladaptive” behavior hasn’t disappeared. (…)

When we focus on particular genes in your particular cortex turning “on” and “off,” the selective forces of evolution aren’t our concern. They’ve done their work; they’re history. But your genes, all “winners” in that eons-long Darwinian process of elimination, still permit a range of human behavior. That range runs from a sober, quiet conscientious life at one extreme to, say, playing for the Rolling Stones at the other. From the long-term genetic point of view, everything on that range, no matter how extreme, is as adaptive as any other. Because the same genes make them all possible.

In other words, the epigenetic idea is that your DNA could support many different versions of you; so the particular you that exists is the result of your experiences, which turned your genes “on” and “off” in patterns that would have been different if you’d lived under different conditions.

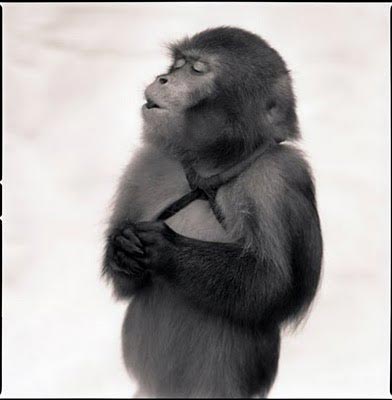

photo { Hiroshi Watanabe }

The history of philosophy abounds in thinkers who, having concluded that the truth is ineffable, have gone on to write page upon page about it. One of the worst offenders is Kierkegaard, who argues in a hundred ways that the ultimate is inexpressible, that truth is “subjectivity,” that the meaning of life can be given by no formula, no proposition, no abstraction, but only by the concrete experience of surrender whose content can never be given in words.

The same idea occurs in Schopenhauer, for whom the truth of the world is Will, which cannot be represented in concepts. Schopenhauer devoted roughly 500,000 words to this thing that no words can capture. And he set a fashion that continues to this day.

I am currently reading a mercifully short book by Vladimir Jankélévitch, Music and the Ineffable, in which the argument is stated on the first page — namely, that since music works through melodies, rhythms and harmonies and not through concepts, it contains no messages that can be translated into words. There follows 50,000 words devoted to the messages of music — often suggestive, poetic and atmospheric words, but words nevertheless, devoted to a subject that no words can capture.

photo { Shelbie Dimond }

Raymond Moore recently described a study about the influence of romance novels on condom use. Erotic romance as a genre generally focuses on spontaneous and passionate sex. Since rubbers don’t exactly scream passion, love scenes rarely mention their use.

Researchers at Northwestern University were interested in how novels affected attitudes toward condom use in readers. They surveyed college students about their reading habits and found that students who read more romance novels had more negative attitudes towards condom use and less intention to use condoms.

photo { Barnaby Roper }

At the forefront of early psychedelic research was a British psychiatrist by the name of Humphry Osmond (1917-2004). In 1951, Osmond moved to Canada to take the position of deputy director of psychiatry at the Weyburn Mental Hospital and, with funding from the government and the Rockefeller Foundation, established a biochemistry research program. The following year, he met another psychiatrist by the name of Abram Hoffer. (…)

The pair hit upon the idea of using LSD to treat alcoholism in 1953, at a conference in Ottawa. (…)

By 1960, they had treated some 2,000 alcoholic patients with LSD, and claimed that their results were very similar to those obtained in the first experiment. Their treatment was endorsed by Bill W., a co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous who was given several sessions of LSD therapy himself, and Jace Colder, director of Saskatchewan’s Bureau on Alcoholism, who believed it to be the best treatment available for alcoholics.

Osmond also “turned on” Aldous Huxley to mescaline, by giving the novelist his first dose of the drug in 1953, which inspired him to write the classic book The Doors of Perception. The two eventually became friends, and Osmond consulted Huxley when trying to find a word to describe the effects of LSD. Huxley suggested phanerothyme, from the Greek words meaning “to show” and “spirit”, telling Osmond: “To make this mundane world sublime/ Take half a gram of phanerothyme.” But Osmond decided instead on the term psychedelic, from the Greek words psyche, meaning “mind”, and deloun, meaning “to manifest”, and countered Huxley’s rhyme with his own: “To fathom Hell or soar angelic/Just take a pinch of psychedelic.” The term he had coined was announced at the meeting of the New York Academy of Sciences in 1957.

LSD therapy peaked in the 1950s, during which time it was even used to treat Hollywood film stars, including luminaries such as Cary Grant.

LSD hit the streets in the early 1960s, by which time more than 1,000 scientific research papers had been published about the drug, describing promising results in some 40,000 patients. Shortly afterwards, however, the investigations of LSD as a therapeutic agent came to an end.

photo { Lina Scheynius }

Words that don’t exist in the english language

L’esprit de escalier (French)

The feeling you get after leaving a conversation, when you think of all the things you should have said. Translated it means “the spirit of the staircase.”Waldeinsamkeit (German)

The feeling of being alone in the woods.Forelsket (Norwegian)

The euphoria you experience when you are first falling in love.Gheegle (Filipino)

The urge to pinch or squeeze something that is unbearably cute.Pochemuchka (Russian)

A person who asks a lot of questions.

artwork { Ana Bagayan }

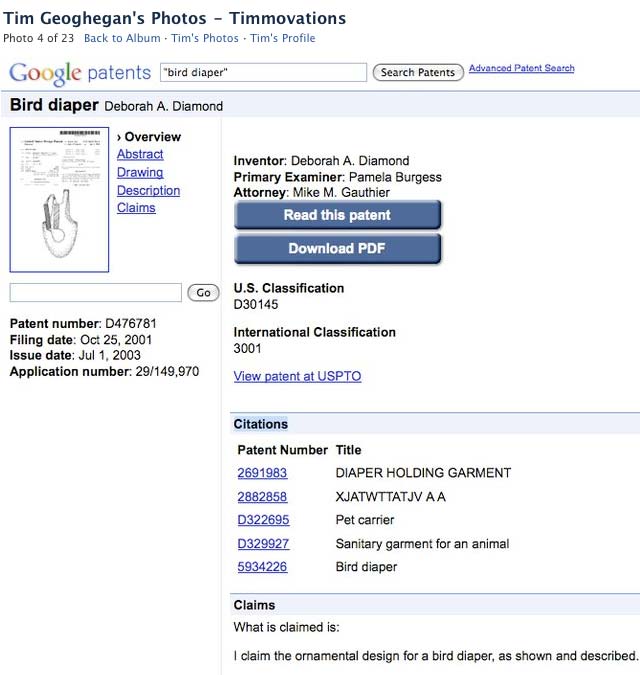

My costume tonight was an over-conceptualized disaster. I always have too many costume ideas. A monthly halloween would be best.

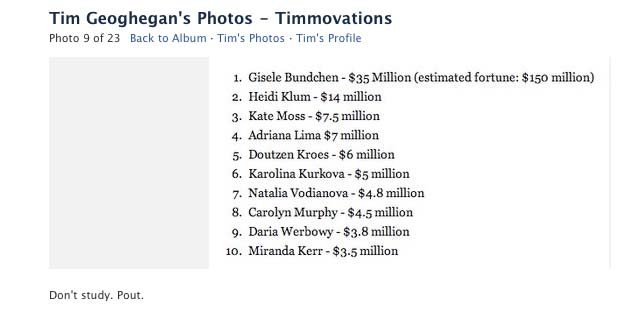

{ Tim Geoghegan | Continue reading | Images: Tim Geoghegan’s Timmovations }