It’s the thought you had in a taxi cab

…an essential difference between genetics, the study of a fixed inheritance in DNA, and epigenetics, which is the study of how the environment affects those genes, causing different ones to be active at different rates, times and places in the body.

Evolutionary approaches to human behavior have often been framed in terms of “good” and “bad”: Why did homosexuality evolve if it’s “bad” for the genes, because it reduces the chance that they’ll be passed on to a new generation? Why wouldn’t an impulsive temperament be “selected against,” seeing as its possessors would be more likely to fall off cliffs? Some thinkers have twisted themselves into pretzels trying to explain why a “maladaptive” behavior hasn’t disappeared. (…)

When we focus on particular genes in your particular cortex turning “on” and “off,” the selective forces of evolution aren’t our concern. They’ve done their work; they’re history. But your genes, all “winners” in that eons-long Darwinian process of elimination, still permit a range of human behavior. That range runs from a sober, quiet conscientious life at one extreme to, say, playing for the Rolling Stones at the other. From the long-term genetic point of view, everything on that range, no matter how extreme, is as adaptive as any other. Because the same genes make them all possible.

In other words, the epigenetic idea is that your DNA could support many different versions of you; so the particular you that exists is the result of your experiences, which turned your genes “on” and “off” in patterns that would have been different if you’d lived under different conditions.

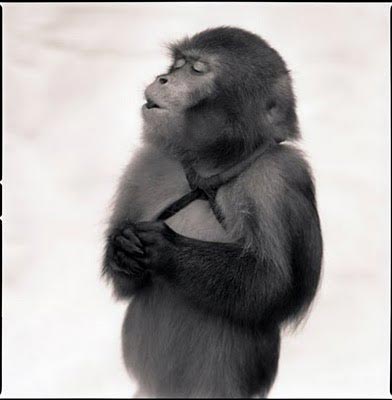

photo { Hiroshi Watanabe }