Epstein had already demonstrated that the continuous and the discontinuous were never opposed to each other in cinema. What are opposed, or at least distinguished, are rather two ways of reconciling them.

Movies are, for the most part, made up of short runs of continuous action, called shots, spliced together with cuts. With a cut, a filmmaker can instantaneously replace most of what is available in your visual field with completely different stuff. This is something that never happened in the 3.5 billion years or so that it took our visual systems to develop. You might think, then, that cutting might cause something of a disturbance when it first appeared. And yet nothing in contemporary reports suggests that it did. […]

What if we could go back in time and collect the reactions of naïve viewers on their very first experience with film editing?

It turns out that we can, sort of. There are a decent number of people on the planet who still don’t have TVs, and the psychologists Sermin Ildirar and Stephan Schwan have capitalised on their existence to ask how first-time viewers experience cuts. […] There was no evidence that the viewers found cuts in the films to be shocking or incomprehensible. […]

I think the explanation is that, although we don’t think of our visual experience as being chopped up like a Paul Greengrass fight sequence, actually it is.

Simply put, visual perception is much jerkier than we realise. First, we blink. Blinks happen every couple of seconds, and when they do we are blind for a couple of tenths of a second. Second, we move our eyes. Want to have a little fun? Take a close-up selfie video of your eyeball while you watch a minute’s worth of a movie on your computer or TV. You’ll see your eyeball jerking around two or three times every second.

Against those who defined Italian neo-realism by its social content, Bazin put forward the fundamental requirement of formal aesthetic criteria. According to him, it was a matter of a new form of reality, said to be dispersive, elliptical, errant or wavering, working in blocs, with deliberately weak connections and floating events. The real was no longer represented or reproduced but “aimed at.” Instead of representing an already deciphered real, neo-realism aimed at an always ambiguous, to be deciphered, real; this is why the sequence shot tended to replace the montage of representations. […]

[I]n Umberto D, De Sica constructs the famous sequence quoted as an example by Bazin: the young maid going into the kitchen in the morning, making a series of mechanical, weary gestures, cleaning a bit, driving the ants away from a water fountain, picking up the coffee grinder, stretching out her foot to close the door with her toe. And her eyes meet her pregnant woman’s belly, and it is as though all the misery in the world were going to be born. This is how, in an ordinary or everyday situation, in the course of a series of gestures, which are insignificant but all the more obedient to simple sensory-motor schemata, what has suddenly been brought about is a pure optical situation to which the little maid has no response or reaction. The eyes, the belly, that is what an encounter is … […] The Lonely Woman [Viaggio in ltalia] follows a female tourist struck to the core by the simple unfolding of images or visual cliches in which she discovers something unbearable, beyond the limit of what she can person- ally bear. This is a cinema of the seer and no longer of the agent.

What defines neo-realism is this build-up of purely optical situations (and sound ones, although there was no synchronized sound at the start of neo-realism), which are fundamentally distinct from the sensory-motor situations of the action-image in the old realism. […]

It is clear from the outset that cinema had a special relationship with belief. […] The modern fact is that we no longer believe in this world. We do not even believe in the events which happen to us, love, death, as if they only halfconcerned us. It is not we who make cinema; it is the world which looks to us like a bad film. […] The link between man and the world is broken. Henceforth, this link must become an object of belief: it is the impossible which can only be restored within a faith. Belief is no longer addressed to a different or transformed world. Man is in the world as if in a pure optical and sound situation.

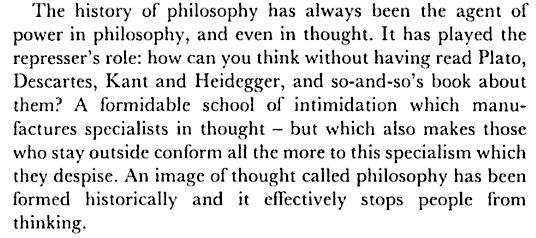

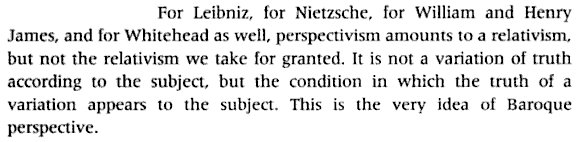

{ Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2, The Time-Image, 1985 | PDF, 17.2 MB }