‘Refrain from total disclosure to basic strangers.’ —Rachel Rosenfelt

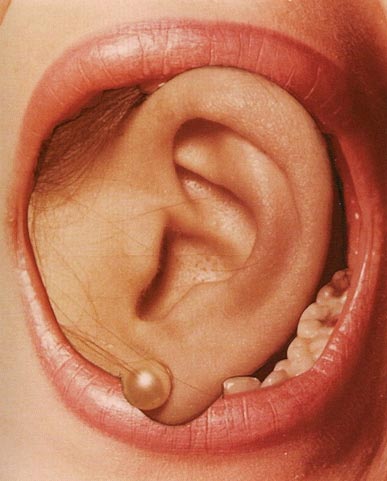

In his story Sarrasine, Balzac, describing a castrato disguised as a woman, writes the following sentence: “This was woman herself, with her sudden fears, her irrational whims, her instinctive worries, her impetuous boldness, her fussings, and her delicious sensibility.” Who is speaking thus? Is it the hero of the story bent on remaining ignorant of the castrato hidden beneath the woman? Is it Balzac the individual, furnished by his personal experience with a philosophy of Woman? Is it Balzac the author professing ‘literary’ ideas on femininity? Is it universal wisdom? Romantic psychology? We shall never know, for the good reason that writing is the destruction of every voice, of every point of origin. Writing is that neutral, composite, oblique space where our subject slips away, the negative where all identity is lost, starting with the very identity of the body writing.

{ Roland Barthes, The Death of the Author, 1967 | Continue reading }