ideas

Intelligence Hierarchy: Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom

Data: Data is the raw building blocks; it consists of raw numbers, but lack context or meaning. 1,200, 9.6%, and $170k are all piece of data.

Information: Is the application of structure or order to data, in an attempt to communicate meaning. Knowing the S&P500 is at 1,200 (up 5% YTD), Unemployment is at 9.6% (down from 11%), and GDP is 2.5% (revised from 2%) are examples.

Knowledge: An understanding of a specific subject, through experience (or education). Typically, knowledge is used in terms of a persons skills or expertise in a given area. Knowledge typically reflects an empirical, rather than intuitive, understanding. Plato referenced it as “justified true belief.”

Wisdom: Optimum judgment, reflecting a deep understanding of people, things, events or situations. A person who has wisdom can effectively apply perception and knowledge in order to produce desired results. Comprehending objectively reality within a broader context.

{ via Barry Ritholtz | Continue reading }

photo { Justin Fantl }

ideas | December 2nd, 2010 4:15 pm

What are we to do when people disagree with one another? Is it possible for one argument to be right while another is wrong? Or is everything just a matter of opinion?

In some cases, there is a way to tell good arguments from bad using what is called informal logic. This name distinguishes it from formal logic, which is used in mathematics; natural language is less precise than mathematics, and does not always follow the same rules. (…)

The distinction between validity and truth is important. Technically, logic cannot establish truth; logic can only establish validity. Validity is still useful. If an argument is valid and the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true. Once we know that an argument is valid, the premises are the only possible source of disagreement.

{ Ars Technica | Continue reading }

photo { Bob O’Connor }

ideas | December 2nd, 2010 3:04 pm

Why does a child grow up to become a lawyer, a politician, a professional athlete, an environmentalist or a churchgoer?

It’s determined by our inherited genes, say some researchers. Still others say the driving force is our upbringing and the nurturing we get from our parents.

But a new child-development theory bridges those two models, says psychologist George W. Holden at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. Holden’s theory holds that the way a child turns out can be determined in large part by the day-to-day decisions made by the parents who guide that child’s growth.

Parental guidance is key. Child development researchers largely have ignored the importance of parental “guidance,” Holden says. In his model, effective parents observe, recognize and assess their child’s individual genetic characteristics, then cultivate their child’s strengths.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

kids, science, theory | December 2nd, 2010 2:01 pm

{ Flag of the International Federation of Vexillological Associations. | Vexillology is the scholarly study of flags. The Latin word vexillum means “flag.” The term was coined in 1957 by the American scholar Whitney Smith. It was originally considered a sub-discipline of heraldry. It is sometimes considered a branch of semiotics. | Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Linguistics, visual design | December 1st, 2010 10:30 pm

A proposal to classify happiness as a psychiatric disorder.

It is proposed that happiness be classified as a psychiatric disorder and be included in future editions of the major diagnostic manuals under the new name: major affective disorder, pleasant type. In a review of the relevant literature it is shown that happiness is statistically abnormal, consists of a discrete cluster of symptoms, is associated with a range of cognitive abnormalities, and probably reflects the abnormal functioning of the central nervous system. One possible objection to this proposal remains–that happiness is not negatively valued. However, this objection is dismissed as scientifically irrelevant.

{ PubMed }

related { A startling proportion of the population, the existentially indifferent, demonstrates little concern for meaning in their lives. }

photo { Rob Hann }

psychology, science, theory | November 30th, 2010 6:06 pm

Here’s the official line on the prize from The Literary Review:

The Bad Sex Awards were inaugurated in 1993 in order to draw attention to, and hopefully discourage, poorly written, redundant or crude passages of a sexual nature in fiction. The intention is not to humiliate.

(…)

And Adam Ross also made the short list for the well-regarded novel “Mr. Peanut,” which includes:

“Love me!” she moaned lustily. “Oh, Ward! Love me now!”

He jumped out from his pajama pants so acrobatically it was like a stunt from Cirque du Soleil. But when he went to remove her slip, she said, “Leave it!” which turned him on even more. He buried his face into Hannah’s cunt like a wanderer who’d found water in the desert. She tasted like a hot biscuit flavored with pee.

{ New Yorker | Continue reading }

books, haha, sex-oriented | November 30th, 2010 3:15 pm

Is it OK to boil a lobster? (…)

Let’s consider the life, or rather the death, of a lobster. In nature lobsters begin very small and die a million horrible deaths in a million horrible ways. As they get older the death rate drops. We have ample evidence that lobsters do not go gentle into that good night, dying peacefully in their sleep at a ripe old age. Instead, once mature, a lobster that doesn’t go into the pot might face off with cod, flounder, an eel or two, or one of many diseases.

Considering that one of the natural deaths a lobster may face is to be torn limb from limb by an eel, getting tossed into a pot of boiling water doesn’t seem quite so gruesome. But there is a big difference between death by eel and death by human, the eel is not human. And now we have hit upon the broader question that must be answered before we can understand the short answer given above: Are humans a part of nature, or apart from nature?

{ The Science Creative Quaterly | Continue reading }

photo { Bill Owens }

animals, food, drinks, restaurants, ideas | November 30th, 2010 2:15 pm

There is the inner life of thought which is our world of final reality. The world of memory, emotion, feeling, imagination, intelligence and natural common sense, and which goes on all the time consciously or unconsciously like the heartbeat.

There is also the thinking process by which we break into that inner life and capture answers and evidence to support the answers out of it.

And that process of raid, or persuasion, or ambush, or dogged hunting, or surrender, is the kind of thinking we have to learn, and if we don’t somehow learn it, then our minds line us like the fish in the pond of a man who can’t fish.

{ Ted Hughes | via MindHacks }

photo { Wai Lin Tse }

ideas | November 29th, 2010 6:39 pm

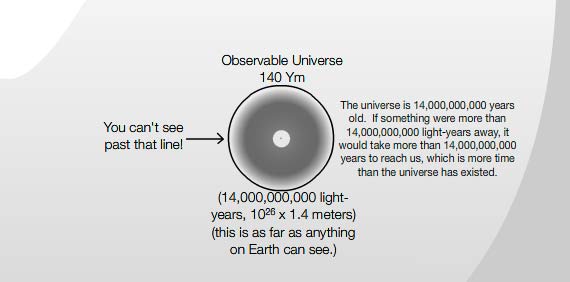

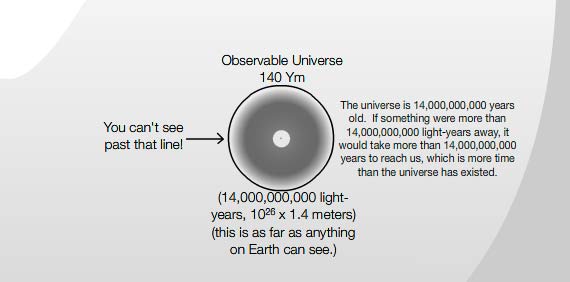

The universe seems vast, distant, and unknowable. It is, for example, unimaginably large and old: The number of stars in our galaxy alone exceeds 100 billion, and the Earth is 4.5 billion years old. In the eyes of the universe, we’re nothing. (…)

Clearly, our brains are not built to handle numbers on this astronomical scale. While we are certainly a part of the cosmos, we are unable to grasp its physical truths. (…) However, there actually are properties of the cosmos that can be expressed at the scale of the everyday. (…)

It turns out that there is one supernova, a cataclysmic explosion of a star that marks the end of its life, about every 50 years in the Milky Way. The frequency of these stellar explosions fully fits within the life span of a single person, and not even a particularly long-lived one. So throughout human history, each person has likely been around for one or two of these bursts that can briefly burn brighter than an entire galaxy.

On the other hand, while new stars are formed in our galaxy at a faster rate, it is still nice and manageable, with about seven new stars in the Milky Way each year. So, over the course of an average American lifetime, each of us will have gone about our business while nearly 550 new stars were born.

{ Boston Globe | Continue reading }

photo { 美撒guo }

ideas, science, space | November 28th, 2010 10:45 am

The World in 2036

Most of the technologies that are now 25 years old or more will be around; almost all of the younger ones “providing efficiencies” will be gone, either supplanted by competing ones or progressively replaced by the more robust archaic ones. So the car, the plane, the bicycle, the voice-only telephone, the espresso machine and, luckily, the wall-to-wall bookshelf will still be with us.

The world will face severe biological and electronic pandemics, another gift from globalisation. (…)

Companies that are currently large, debt-laden, listed on an exchange and paying bonuses will be gone. Those that will survive will be the more black swan-resistant—smaller, family-owned, unlisted on exchanges and free of debt. There will be large companies then, but these will be new—and short-lived. (…)

Science will produce smaller and smaller gains in the non-linear domain, in spite of the enormous resources it will consume; instead it will start focusing on what it cannot—and should not—do.

{ Nassim Taleb| Continue reading }

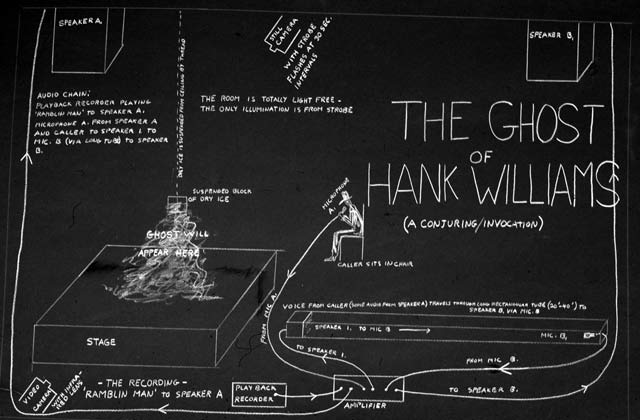

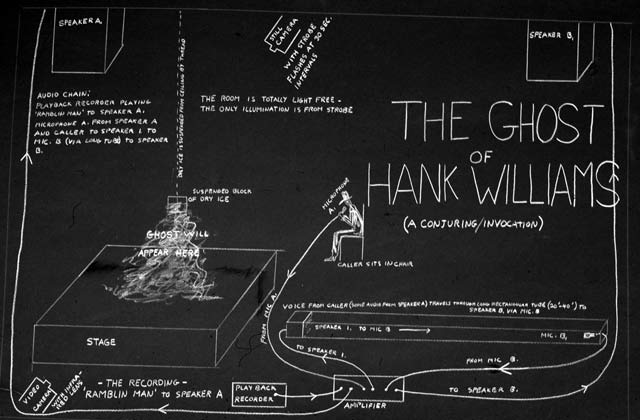

artwork { David Askevold, The Ghost Of Hank Williams, 1979 }

economics, future, ideas | November 26th, 2010 4:50 pm

I wondered for probably the millionth time why I am always running late.

This time, I vowed, I was going to find out.

I turned to an obscure field of neuroscience for answers. The scientists who work on the problem of time in the brain sometimes refer to their area of expertise as “time perception” or “clock timing.” What they’ve discovered is that your brain is one of the least accurate time measurement devices you’ll ever use. And it’s also the most powerful.

When you watch the seconds tick by on a digital watch, you are in the realm of objective time, where a minute-long interval is always 60 seconds. But to your brain, a minute is relative. Sometimes it takes forever for a minute to be over. That’s because you measure time with a highly subjective biological clock.

Your internal clock is just like that digital watch in some ways. It measures time in what scientists call pulses. Those pulses are accumulated, then stored in your memory as a time interval. Now, here’s where things get weird. Your biological clock can be sped up or slowed down by anything from drugs to the way you pay attention. If it takes you 60 seconds to cross the street, your internal clock might register that as 50 pulses if you’re feeling sleepy. But it might register 100 pulses if you’ve just drunk an espresso. That’s because stimulants literally speed up the clock in your brain (more on that later). When your brain stores those two memories of the objective minute it took to cross the street, it winds up with memories of two different time intervals.

And yet, we all have an intuitive sense of how long it takes to cross a street. But how do we know, if every time we do something it feels like it a slightly different amount of time? The answer, says neuroscientist Warren Meck, is “a Gaussian distribution” - in other words, the points on a bell curve. Every time you want to figure out how long something is going to take, your brain samples from those time interval memories and picks one. (…)

Your intuitive sense of how much time something will take is taken at random from many distorted memories of objective time. Or, as Meck puts it, “You’re cursed to be walking around with a distribution of times in your head even though physically they happened on precise time.”

Your internal clock may be the reason why you can multitask. Because nobody - not even the lowly rat - has just one internal clock going at the same time.

At the very least, you’ve got two internal clocks running. One is the clock that tracks your circadian rhythms, telling you when to go to sleep, wake up, and eat. This is the most fundamental and important of all your internal clocks, and scientists have found it running even in organisms like green algae. The other clock you’ve likely got running is some version of the interval time clock I talked about earlier - the one that tells you how long a particular activity is going to take.

{ io9 | Continue reading }

photo { Logan White }

neurosciences, time | November 26th, 2010 4:48 pm

Circular patterns within the cosmic microwave background suggest that space and time did not come into being at the Big Bang but that our universe in fact continually cycles through a series of “aeons.” That is the sensational claim being made by University of Oxford theoretical physicist Roger Penrose, who says that data collected by NASA’s WMAP satellite support his idea of “conformal cyclic cosmology”. This claim is bound to prove controversial, however, because it opposes the widely accepted inflationary model of cosmology.

According to inflationary theory, the universe started from a point of infinite density known as the Big Bang about 13.7 billion years ago, expanded extremely rapidly for a fraction of a second and has continued to expand much more slowly ever since, during which time stars, planets and ultimately humans have emerged. That expansion is now believed to be accelerating and is expected to result in a cold, uniform, featureless universe.

Penrose, however, takes issue with the inflationary picture and in particular believes it cannot account for the very low entropy state in which the universe was believed to have been born – an extremely high degree of order that made complex matter possible. He does not believe that space and time came into existence at the moment of the Big Bang but that the Big Bang was in fact just one in a series of many, with each big bang marking the start of a new “aeon” in the history of the universe.

{ PhysicsWorld | Continue reading }

related { In an experiment to collide lead nuclei together at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider physicists discovered that the very early Universe was not only very hot and dense but behaved like a hot liquid. }

photo { Young Kyu Yoo }

related:

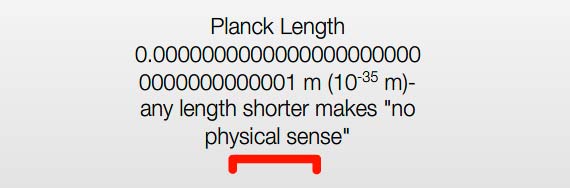

{ The Scale of the Universe }

space, theory, time | November 26th, 2010 4:20 pm

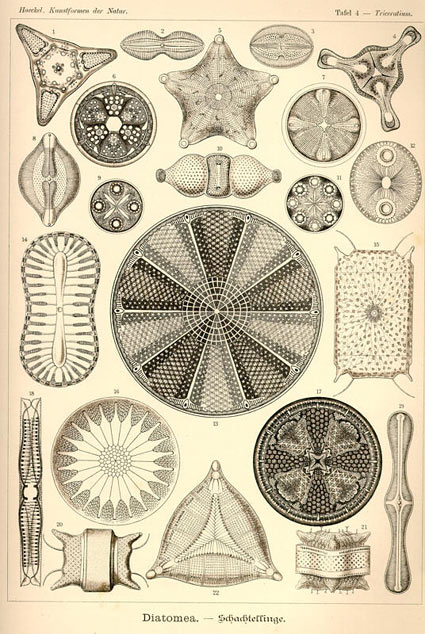

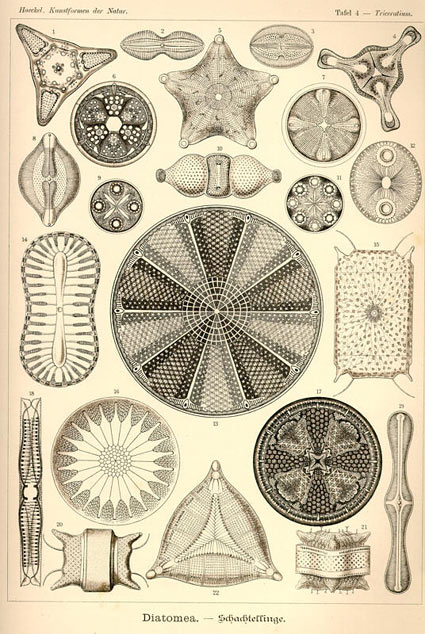

{ Ernst Haeckel, Kunstformen der Natur, 1899-1904 | Ernst Haeckel (1834 – 1919) was an eminent German biologist, naturalist, philosopher, physician, professor and artist who discovered, described and named thousands of new species, mapped a genealogical tree relating all life forms, and coined many terms in biology, including ecology. | Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Linguistics, flashback, science, visual design | November 26th, 2010 4:20 pm

What does it mean to think? Can machines think, or only humans? These questions have obsessed computer science since the 1950s, and grow more important every day as the internet canopy closes over our heads, leaving us in the pregnant half-light of the cybersphere. Taken as a whole, the net is a startlingly complex collection of computers (like brain cells) that are densely interconnected (as brain cells are). And the net grows at many million points simultaneously, like a living (or more-than-living?) organism. It’s only natural to wonder whether the internet will one day start to think for itself. (…)

Today’s mainstream ideas about human and artificial thought lead nowhere. (…) Here are three important wrong assumptions.

Many people believe that “thinking” is basically the same as “reasoning.”

But when you stop work for a moment, look out the window and let your mind wander, you are still thinking. Your mind is still at work. This sort of free-association is an important part of human thought. No computer will be able to think like a man unless it can free-associate.

Many people believe that reality is one thing and your thoughts are something else. Reality is on the outside; the mental landscape created by your thoughts is inside your head, within your mind. (Assuming that you’re sane.)

Yet we each hallucinate every day, when we fall asleep and dream. And when you hallucinate, your own mind redefines reality for you; “real” reality, outside reality, disappears. No computer will be able to think like a man unless it can hallucinate.

Many people believe that the thinker and the thought are separate. For many people, “thinking” means (in effect) viewing a stream of thoughts as if it were a PowerPoint presentation: the thinker watches the stream of his thoughts. This idea is important to artificial intelligence and the computationalist view of the mind. If the thinker and his thought-stream are separate, we can replace the human thinker by a computer thinker without stopping the show. The man tiptoes out of the theater. The computer slips into the empty seat. The PowerPoint presentation continues.

But when a person is dreaming, hallucinating — when he is inside a mind-made fantasy landscape — the thinker and his thought-stream are not separate. They are blended together. The thinker inhabits his thoughts. No computer will be able to think like a man unless it, too, can inhabit its thoughts; can disappear into its own mind.

What does this mean for the internet: will the internet ever think? Will an individual computer ever think?

{ David Gelernter/Edge | Continue reading }

photo { Aristide Briand photographed by Erich Salomon, Paris, 1931 }

ideas, technology | November 24th, 2010 5:30 pm

Most jerks, I assume, don’t know that they’re jerks. This raises, of course, the question of how you can find out if you’re a jerk. I’m not especially optimistic on this front. (…)

Another angle into this important issue is via the phenomenology of being a jerk. I conjecture that there are two main components to the phenomenology:

First: an implicit or explicit sense that you are an “important” person. (…) What’s involved in the explicit sense of feeling important is, to a first approximation, plain enough. The implicit sense is perhaps more crucial to jerkhood, however, and manifests in thoughts like the following: “Why do I have to wait in line at the post office with all the schmoes?” and in often feeling that an injustice has been done when you have been treated the same as others rather than preferentially.

Second: an implicit or explicit sense that you are surrounded by idiots.

{ Eric Schwitzgebel | Continue reading }

illustration { David Bray, Better Must Come, 2009 }

ideas | November 23rd, 2010 4:57 pm

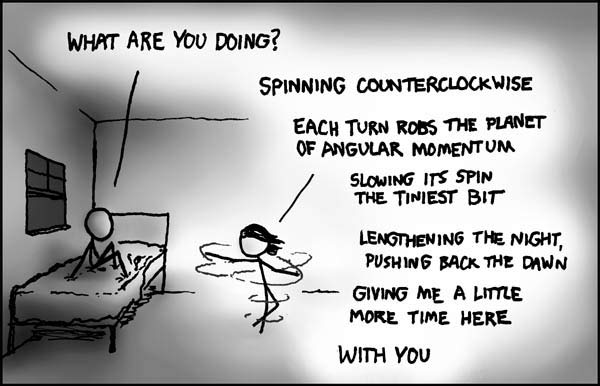

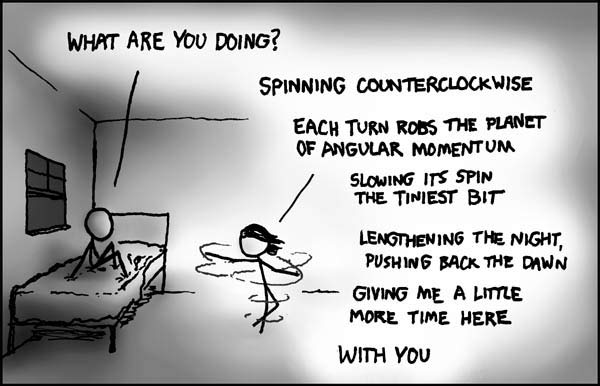

{ xkcd }

relationships, time, visual design | November 23rd, 2010 4:22 pm

The simulation argument purports to show, given some plausible assumptions, that at least one of three propositions is true.

Roughly stated, these propositions are: (1) almost all civilizations at our current level of development go extinct before reaching technological maturity; (2) there is a strong convergence among technologically mature civilizations such that almost all of them lose interest in creating ancestor‐simulations; (3) almost all people with our sorts of experiences live in computer simulations.

I also argue (#) that conditional on (3) you should assign a very high credence to the proposition that you live in a computer simulation. However, pace Brueckner, I do not argue that we should believe that we are in simulation.

In fact, I believe that we are probably not simulated. The simulation argument purports to show only that, as well as (#), at least one of (1) ‐ (3) is true; but it does not tell us which one.

{ Nick Bostrom, The simulation argument: Some Explanations, 2008 | Continue reading | PDF }

photo { Santiago Mostyn }

ideas | November 22nd, 2010 8:26 pm

I use a method called “Dutching” (named for 1930s New York gangster, “Dutch” Schultz, whose accountant came up with it). With Dutched bets, you make two or more bets on the same race with more money on more favored horses and less money on longer odds horses such that your profit is the same, no matter which horse wins. (…)

I haven’t bet with this strategy yet, but I have found from playing with the data that very often there are opportunities…

{ David Icke’s Official Forums | Wikipedia }

Arthur Flegenheimer, alias Dutch Shultz, was a fugitive from justice. He was wanted in 1934 for Income Tax Evasion. On October 23, 1935, Shultz and three associates were shot by rival gangsters in a Newark, New Jersey restaurant. Shultz’s death started rival gang wars among the hoodlum and underworld gangs.

{ FBI.gov | Continue reading | Read more: By the mid-1920s, Schultz realized that bootlegging was the way to make serious money. }

Linguistics, flashback, horse, law | November 22nd, 2010 8:06 pm

I hate to be the one to tell you this, but there’s a whole range of phrases that aren’t doing the jobs you think they’re doing.

In fact, “I hate to be the one to tell you this” (like its cousin, “I hate to say it”) is one of them. Think back: How many times have you seen barely suppressed glee in someone who — ostensibly — couldn’t be more reluctant to be the bearer of bad news? A lack of respect from someone who starts off “With all due respect”? A stunning dearth of comprehension from someone who prefaces their cluelessness with “I hear what you’re saying”? And has “I’m not a racist, but…” ever introduced an unbiased statement?

These contrary-to-fact phrases have been dubbed (by the Twitter user GrammarHulk and others) “but-heads,” because they’re at the head of the sentence, and usually followed by but. They’ve also been dubbed “false fronts,” “wishwashers,” and, less cutely, “lying qualifiers.”

The point of a but-head is to preemptively deny a charge that has yet to be made, with a kind of “best offense is a good defense” strategy. This technique has a distinguished relative in classical rhetoric: the device of procatalepsis, in which the speaker brings up and immediately refutes the anticipated objections of his or her hearer. When someone says “I’m not trying to hurt your feelings, but…” they are maneuvering to keep you from saying “I don’t believe you — you’re just trying to hurt my feelings.”

Once you start looking for these but-heads, you see them everywhere, and you see how much they reveal about the speaker. When someone says “It’s not about the money, but…”, it’s almost always about the money. If you hear “It really doesn’t matter to me, but…”, odds are it does matter, and quite a bit. Someone who begins a sentence with “Confidentially” is nearly always betraying a confidence; someone who starts out “Frankly,” or “Honestly,” “To be (completely) honest with you,” or “Let me give it to you straight” brings to mind Ralph Waldo Emerson’s quip: “The louder he talked of his honor, the faster we counted our spoons.”

{ Boston Globe | Continue reading }

ideas, shit talkers | November 22nd, 2010 11:44 am

Happiness is ideal, it’s the work of the imagination. It’s a way of being moved which depends solely on our way of seeing and feeling. Except for the satisfaction of needs, there’s nothing that makes all men equally happy.

{ Sade, The Crimes of Love, 1800 }

photo { Jesse Kennedy }

ideas, relationships | November 20th, 2010 3:58 pm