‘When we love a thing similar to ourselves we endeavour, as far as we can, to bring about that it should love us in return.’ –Spinoza

{ Chuppé | Imp Kerr & Associates, NYC }

{ Chuppé | Imp Kerr & Associates, NYC }

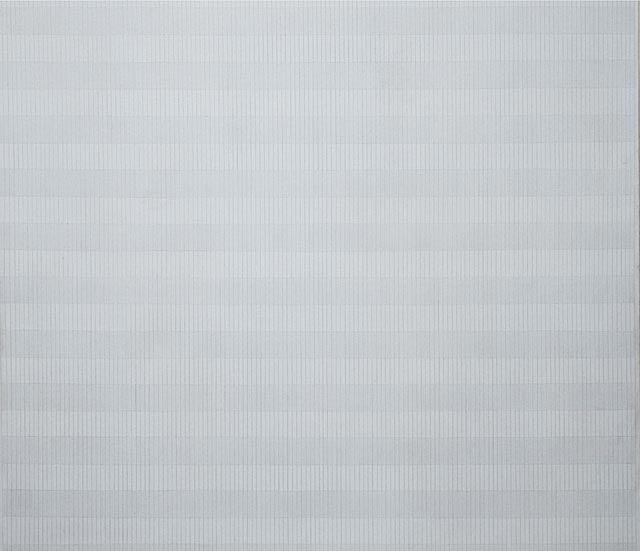

{ Agnes Martin, The Tree, 1964 | oil and pencil on canvas | Of the genesis of her paintings, Martin said, “When I first made a grid I happened to be thinking of the innocence of trees and then this grid came into my mind and I thought it represented innocence, and I still do.” }

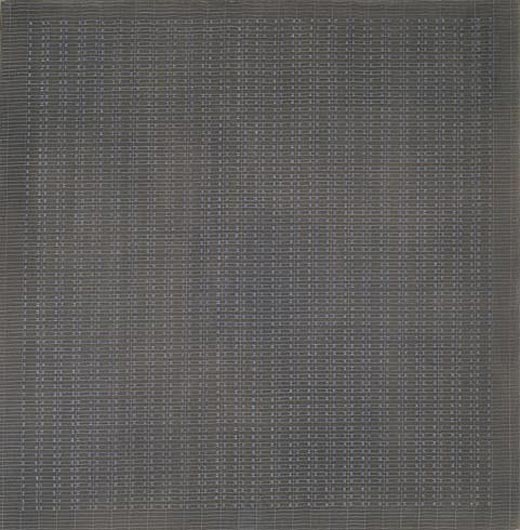

{ Agnes Martin, White Flower, 1960 | oil on canvas }

{ Agnes Martin Interview, 1997 | via Doug/Ed }

vaguely related { Paintings worth up to $613 million stolen in Paris. British art crime investigator Dick Ellis, director of Art Management Group, said: “If these estimates of the value are true then this could be the biggest theft in history. | more }

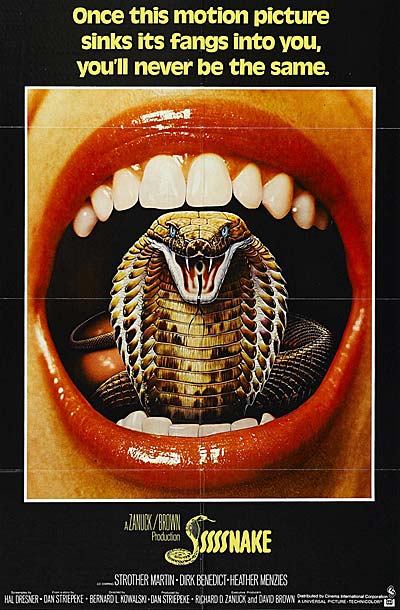

How spitting cobras shoot for the eyes

Bruce Young from the University of Massachusetts is antagonising a spitting cobra. He approaches, keeping outside of the snake’s strike radius, while moving his head from side to side. The cobra doesn’t like it and erects its hood in warning. Young persists, and the snake retaliates by launching twin streams of venom at him from forward-facing holes in its fangs. The aim is spot-on: right at Young’s eyes. Fortunately, he is wearing a Perspex visor that catches the spray; without it, the venom would start destroying his corneas, giving him minutes to seek medical aid before permanent blindness set in.

It may seem a bit daft to provoke a snake that can poison you from afar, but Young’s antics were all part of an attempt to show just how spitting cobras make their shots. Their venom is a potent defensive weapon, but it’s also completely useless if it lands on the skin or even in the mouth. To work, the cobra must aim for the eyes.

Just think about how hard that is. The cobra must hit a moving target that’s up to 1.5 metres away, using a squirt gun attached to their mouth. The fang is fixed with no movable nozzle for fine-tuned aiming. And the venom spray lasts just 50 milliseconds – not long enough to correct the stream after watching its arc.

By taunting cobras from behind his visor, Young discovered their secret. The snake waits for a particularly jerky movement to trigger its attack and synchronise the movements of its heads in the same way. It shakes its head rapidly from side to side to achieve a wide spray of venom. And it even predicts the position of its target 200 milliseconds later and shoots its venom at where its eyes are going to be.

{ Janice Guy’s untitled self-portraits, 1979 | Janice Guy abandoned art making in the early 1980s and is now better known as the co-director of the New York gallery Murray Guy. | More: Janice Guy’s exhibition at White Columns, 2008 }

Things that appear on the left are better remembered

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether neurologically intact individuals demonstrate a lateralized bias in remembering mental images of recently presented novel material comprising arbitrary combinations of shape, colour, and location in a temporary memory binding paradigm. The material involved arrays of a small number of simple geometric or animal shapes, so as to make it very unlikely that there would be any difficulties in perception, thereby focusing on memory. Recall was assessed by asking participants to report stimulus features using a forced-choice task in which they selected the colour, shape, and location of each item shown in the study array. In three related experiments, we report evidence of a new phenomenon: a leftward bias when people try to remember visually presented novel information.

During REM sleep, where most dreaming takes place, your eyes move around but it’s never been clear exactly why. A new study just published online by neuroscience journal Brain suggests that they are looking at the ever-changing dream world.

The first question you might ask is how the researchers knew what the dreamers were looking at. To study this, the project recruited people with a condition called REM sleep behaviour disorder who lack the normal sleep paralysis that keeps us still when we dream.

In other words, people with REM sleep behaviour disorder act out their dreams. (…) When the eyes move during REM sleep they are looking at something in the dream world. The eyes seem genuinely to be a bridge between the land of dream consciousness and waking life.

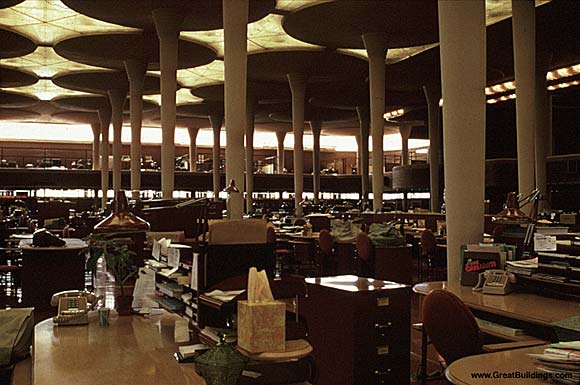

{ Frank Lloyd Wright, Johnson Wax Building, Wisconsin, 1936-1944 | Main room with lily-pad columns | more photos }

The construction of the Johnson Wax building created controversies for the architect. In the Great Workroom, the dendriform columns are 9 inches (23 cm) in diameter at the bottom and 18 feet (550 cm) in diameter at the top, on a wide, round platform that Wright termed, the “lily pad.” This difference in diameter between the bottom and top of the column did not accord with building codes at the time. Building inspectors required that a test column be built and loaded with twelve tons of material. The test column, once it was built, was tough enough that it was able to be loaded fivefold with sixty tons of materials before the “calyx”, or part of the column that meets the lily pad, cracked (crashing the 60 tons of materials to the ground, and bursting a water main 30 feet underground). After this demonstration, Wright was given his building permit.

related:

New research shows a possible explanation for the link between mental health and creativity. By studying receptors in the brain, researchers at the Swedish medical university Karolinska Institutet have managed to show that the dopamine system in healthy, highly creative people is similar in some respects to that seen in people with schizophrenia.

High creative skills have been shown to be somewhat more common in people who have mental illness in the family. Creativity is also linked to a slightly higher risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Certain psychological traits, such as the ability to make unusual pr bizarre associations are also shared by schizophrenics and healthy, highly creative people. And now the correlation between creativity and mental health has scientific backing.

photo { Alison Brady }

Subjective experience poses a major problem for neuroscientists and philosophers alike, and the relationship between them and brain function is particularly puzzling. How can I know that my perception of the colour red is the same as yours, when my experience of the colour occupies a private mental world to which nobody else has access? How is the sensory information from an object transformed into an experience that enters conscious awareness? The neural mechanisms involved are like a black box, whose inner workings are a complete mystery.

In synaesthesia, the information entering one sensory system gives rise to sensations in another sensory modality. Letters can evoke colours, for example, and movements can evoke sounds. These extraordinary additional sensations therefore offer a unique opportunity to investigate how the subjective experiences of healthy people are related to brain function. Dutch psychologists now report that different types of synaesthetic experiences are associated with different brain mechanisms, providing a rare glimpse into the workings of the black box.

photo { Werner Amann }

Men are far more likely to tell lies than women, researchers have revealed.

Their study found that the average male tells 1,092 lies every year - roughly three a day.

By contrast, the average woman will lie 728 times a year - around twice a day.

And while men said their lies were most likely to relate to their drinking habits, the most popular female fib - ‘Nothing’s wrong, I’m fine’ - hides their true feelings.

Men are also less likely to feel guilty about lying. (…)‘The jury is still out as to whether human quirks like lying are the result of genes, evolution or upbringing.’

According to the findings, we are most likely to spin a yarn to our mothers, with 25 per cent of men and 20 per cent of women admitting to this.

{ When it comes to secure messaging, nothing beats quantum cryptography, a method that offers perfect security. Messages sent in this way can never be cracked by an eavesdropper, no matter how powerful. At least, that’s the theory. Today, physicists say they have broken a commercial quantum cryptography system made by the Geneva-based quantum technology startup ID Quantique, the first successful attack of its kind on a commercially-available system. | The Physics arXiv Blog | full story }

photos { Guy le Baube | Daemian and Christine }

quote { via Orion Magazine }

To those who know his name at all in America, Jean Eustache may be a one-hit wonder. But in France he’s far and away the most important filmmaker of the post–New Wave era. Eustache left an indelible mark on French cinema and exercised a profound influence on such directors as Olivier Assayas, Catherine Breillat, Claire Denis, Philippe Garrel, and Benoit Jacquot. His 1973 The Mother and the Whore is the kind of movie that few filmmakers even allow themselves to conindex, let alone make: brutally honest as self-portraiture, as frank about human relationships (sexual and otherwise) as movies have ever gotten, and the last word on post-’68 bohemian Paris. Eustache died before his time (by his own hand) in 1981. Often likened to John Cassavetes, he stands alone as a unique and visionary practitioner of the art.

Une sale histoire (A Dirty Story), directed by Jean Eustache, 1977

In A Dirty Story Jean Eustache presents the same story of storytelling twice: once in documentary fashion, filmed his friend Jean-Noël Picq in 16mm black and white, and a second time in 35mm color with the actor Michael Lonsdale reciting the same lines. Eustache invited his Jean-Noël Picq to sit down with a group of people to recount in detail how once, in the men’s room of a Parisian restaurant, he found a hole in the wall and peered through to a perfect view of the ladies’ room. In order to test his contention that the actor would prove more convincing than the real-life storyteller, Eustache placed the fictional version first. While the film never shows anything more shocking than a man talking, French censors gave the film an X rating, proving Eustache’s claim that “sex has nothing to do with morals, not even with aesthetics; sex is a metaphysical affair.”

Full second part (unsubtitled):

I publish this column every year as a public service to make sure your friends and relatives will think twice before they send you an invitation that will screw you out of a precious summer weekend.

Why do they do it?

Why do our friends and relatives destroy the summer for us? Why can’t they get married in February? Why do they choose the middle of summer to have birthdays, anniversaries, Bar Mitzvahs, family, college, high school and even nursery school reunions? That’s not all. Frankly, some of them are thoughtless enough to die in June, July and August, and there goes another summer weekend.

I promise that if it’s possible, when it’s time for me to go, I will go on life support until some rainy Friday morning in January so that my mourners can bury me early in the morning and still enjoy a three-day weekend. That’s the kind of generous guy I am. (…)

Which brings me to summer weddings in the city. They must be banned.

There are some facts that people who drag their friends away from the beach for their wedding must be made aware of. Jerry Seinfeld, an East Hampton resident, had a message for all the newly engaged couples: “Nobody wants to go to your wedding! We are not excited like you are.”

The Type A and Type B personality theory is a personality type theory that describes a pattern of behaviors that were once considered to be a risk factor for coronary heart disease. Since its inception in the 1950s, the theory has been widely criticized for its scientific shortcomings. It nonetheless persists in the form of pop psychology within the general population.

Type A individuals can be described as impatient, time-conscious, controlling, concerned about their status, highly competitive, ambitious, business-like, aggressive, having difficulty relaxing; and are sometimes disliked by individuals with Type B personalities for the way that they’re always rushing. They are often high-achieving workaholics who multi-task, drive themselves with deadlines, and are unhappy about delays. Because of these characteristics, Type A individuals are often described as “stress junkies.”

Type B individuals, in contrast, are described as patient, relaxed, and easy-going, generally lacking an overriding sense of urgency. Because of these characteristics, Type B individuals are often described by Type A’s as apathetic and disengaged.

There is also a Type AB mixed profile for people who cannot be clearly categorized.

Type A behavior was first described as a potential risk factor in coronary disease in the 1950s by cardiologists Meyer Friedman and R. H. Rosenman. After a nine-year study of healthy men, aged 35–59, Friedman & Rosenman estimated that Type A behavior doubles the risk of coronary heart disease in otherwise healthy individuals. This research had an enormous effect in stimulating the development of the field of health psychology, in which psychologists look at how a person’s mental state affects his or her physical health.

photo { Abbey Drucker }

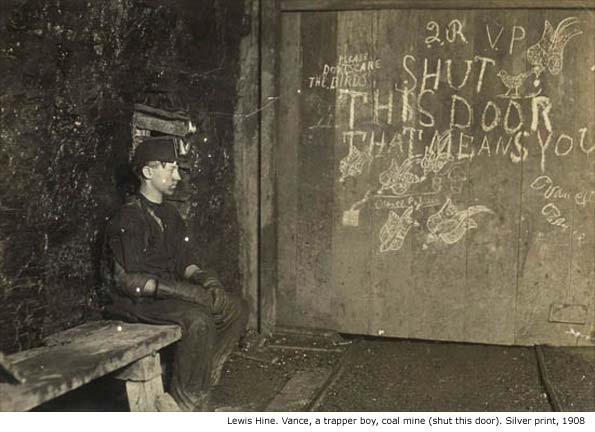

{ Vance, a trapper boy, 15 years old. Has trapped for several years in a West Virginia coal mine at 75 cents a day for 10 hours work. All he does is to open and shut this door: most of the time he sits here idle, waiting for the cars to come. | BBC | more }

The advice of etiquette experts on dealing with unwanted invitations, or overly demanding requests for favours, has always been the same: just say no. That may have been a useless mantra in the war on drugs, but in the war on relatives who want to stay for a fortnight, or colleagues trying to get you to do their work, the manners guru Emily Post’s formulation – “I’m afraid that won’t be possible” – remains the gold standard. (…) These are variations on a theme: the best way to say no is to say no. Then shut up. (…)

There are certainly profound issues here, of self-esteem, guilt, et cetera. But it’s also worth considering whether part of the problem doesn’t originate in a simple misunderstanding between two types of people: Askers and Guessers.

This terminology comes from a brilliant web posting by Andrea Donderi. We are raised, the theory runs, in one of two cultures.

In Ask culture, people grow up believing they can ask for anything – a favour, a pay rise– fully realising the answer may be no. In Guess culture, by contrast, you avoid “putting a request into words unless you’re pretty sure the answer will be yes… A key skill is putting out delicate feelers. If you do this with enough subtlety, you won’t have to make the request directly; you’ll get an offer. Even then, the offer may be genuine or pro forma; it takes yet more skill and delicacy to discern whether you should accept.”

Neither’s “wrong”, but when an Asker meets a Guesser, unpleasantness results. An Asker won’t think it’s rude to request two weeks in your spare room, but a Guess culture person will hear it as presumptuous and resent the agony involved in saying no. Your boss, asking for a project to be finished early, may be an overdemanding boor – or just an Asker, who’s assuming you might decline.

If you’re a Guesser, you’ll hear it as an expectation. This is a spectrum, not a dichotomy, and it explains cross-cultural awkwardnesses, too: Brits and Americans get discombobulated doing business in Japan, because it’s a Guess culture, yet experience Russians as rude, because they’re diehard Askers.

The amount of stress we endure is increasing because of our focus on efficiency. Stress is caused by uncertainty, more specifically, by doubts in our ability to handle something. As machines and computers handle more things that are predictable and certain, we are pressured to deal with more things that are unpredictable and uncertain. This inevitably leads to more stress. As soon as our tasks become predictable and certain, we automate them using our technology. The result of this process of streamlining is that we are increasingly called upon to use our, what I would call, irrational abilities, such as instincts, sensibilities, creativities, and interpersonal skills. These things are, by nature, unpredictable.

Take stock trading, for instance. When there were no computers to process the trades, the number of trades you could do in a day was limited. A certain amount of your work as a trader involved processing of paperwork, communicating with others, and doing some arithmetic; tasks that are predictable and not stressful. Today, a click of a button essentially takes care of all of those predictable tasks, and you skip right ahead to another stressful decision-making.

As another example, take graphic designers. Now with computers handling everything from typesetting, layout, image processing, color management to printing, what used to be done by several specialists are now combined into one person. The number of jobs one can handle in a year increased dramatically. Now designers spend more time being creative, and less time creating the final products. This may sound good, but in terms of stress and rewards, it is not. Because creativity is irrational and unpredictable, coming up with a creative solution can be highly stressful. Designers now have to come up with significantly more creative solutions per year for the same amount of money. (…)

Despite all the stresses we deal with in our lives, we feel that we are running towards nowhere, very much like running on a treadmill. I believe this is because the whole nation, the whole economy, is on a treadmill. In analyzing our economic growth, we focus on matters that are actually irrelevant to our feelings. We falsely believe that technological advancement, increase in production, and providing greater choice would make us happier, but we have more indications to the contrary.

photo { Robert Whitman }