Every day, the same, again

Funeral home accused of losing woman’s body.

Funeral home accused of losing woman’s body.

Bull semen canisters fall off bus, close highway ramp.

Study finds bacteria from dog feces in winter sky above Detroit.

Hoax sign warns Arizona drivers of panda rampage.

When sheriff’s deputies raided a suspected meth house in Loma Linda, the drugs, guns and pipes were there, as expected. But the discovery of about two dozen granite tombstones had them stumped.

Drunk Gerard Depardieu kicked off plane after peeing on floor. Passengers shocked, but friends of beloved French actor insist he urinated in a bottle.

Why Earthquake Shook NYC Skyscrapers, But Not Streets.

Will Hurricane Irene Destroy NYC?

A New York Hurricane Could Be a Multibillion-Dollar Catastrophe.

Warren Buffett Bails Out Bank of America.

Mortgage Rates Hit 50-Year Low.

Steve Jobs, in multiple stages of his business career, changed global technology, media and lifestyles in multiple ways on multiple occasions. Related: The 313 Apple patents that list Steven P. Jobs among the group of inventors.

Computers will be able to tell social traits from the face.

Psychologist James Pennebaker reveals the hidden meaning of pronouns.

How Do I Remember That I Know You Know That I Know?

More people means more ideas. In the long run.

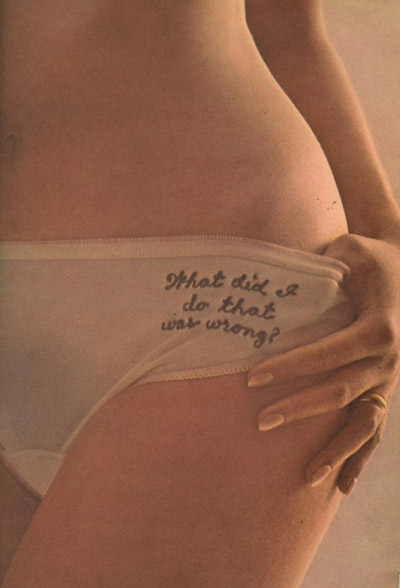

Less depression for working moms who expect that they ‘can’t do it all.’

Climate cycles are driving wars, says study.

Stars as cool as the human body discovered.

Stars as cool as the human body discovered.

Lava, not water, may have carved the biggest channels on Mars.

If we can’t see black holes, how do we know they’re there? Well, orbits, for one thing.

Researchers discovered a new species of titi monkey on a recent expedition to the Brazilian amazon.

The way bees hunt for food is more complex than biologists thought.

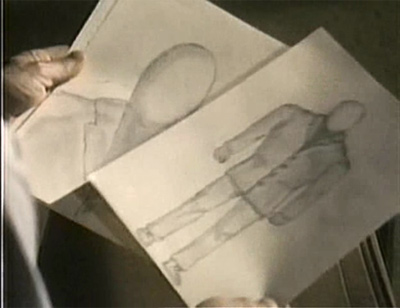

Conjoined twinning is a rare congenital abnormality. We know of old historical cases, of course, like Chang and Eng, whose birthplace gives us the term Siamese twins. Solving the Mystery of Conjoined Twins at Angel Mounds.

Billie Holiday sings about the phenomenon of seeing meaningful patterns in vague or non-connected visual information in her well-known track The Very Thought of You. Scientifically, these effects are known as pareidolia or apophenia.

Do You See What I See? BBC on the Subjectivity of Color Perception. Why you should wear red on your next date, or what an African tribe can teach us about the color of water.

Why Fallacies Appear to Be Better Arguments than They Are.

If religion makes you happy, why are people turning away from it?

The question of whether the world is finite or infinite has bedeviled us for a long time.

How Computational Complexity Will Revolutionize Philosophy.

Merkle Puzzles in a Quantum World. In 1974, Ralph Merkle proposed the first unclassified scheme for secure communications over insecure channels.

It is useful to think of conspiracy theorizing as a meme, a cultural invention that passes from one mind to another and thrives, or declines, through a process analogous to genetic selection.

It is useful to think of conspiracy theorizing as a meme, a cultural invention that passes from one mind to another and thrives, or declines, through a process analogous to genetic selection.

The Voynich Manuscript: will we ever be able to read this book?

Grue and bleen are artificial predicates, coined as two portmanteau of “green” and “blue” by philosopher Nelson Goodman. The words are used to illustrate what Goodman calls “the new riddle of induction.”

The business of writing about the business of roller coasters.

How Vodka, the flavorless, colorless, odorless spirit, became a billion-dollar business.

Why Reindeer Don’t Go Snowblind.

How Ayrton Senna Car Crash Saved Formula One Racing.

How Do You Count 7 Billion People?

What did people use before toilet paper was invented?

A lot / Alot / Allot. First the bad news: there is no such word as “alot.” “A lot” refers to quantity, and “allot” means to distribute or parcel out. 7 Spelling and Grammar Errors that Make You Look Dumb.

Created in 1997, the Taco Bell Chihuahua was the fast-food chain’s big attempt to establish a mascot for their brand. Common logic must have been the driving force here, as Taco Bell is a fake Mexican restaurant, and the Chihuahua is a fake Mexican dog. 5 Famous Ad Campaigns That Actually Hurt Sales.

Left: 100-year-old logo for a defunct company called S & Co. Right: Goodby Silverstein & Partners new logo. Appropriation is a big part of our culture.

Left: 100-year-old logo for a defunct company called S & Co. Right: Goodby Silverstein & Partners new logo. Appropriation is a big part of our culture.

Toasted bread portraits. Related: Mother-in-law recreated with huge toast portrait.

Shark alarm. [video]

If I could get that dressmaker to make a concertina skirt like Susy Nagle’s

The Experiment: Split up twins after birth—and then control every aspect of their environments.

The payoff: Several disciplines would benefit enormously, but none more than psychology, in which the role of upbringing has long been particularly hazy. Developmental psychologists could arrive at some unprecedented insights into personality—finally explaining, for example, why twins raised together can turn out completely different, while those raised apart can wind up very alike.

Maggy, pouring yellow soup in Katey’s bowl, exclaimed: Boody! For shame!

A woman who took her partner’s name or a hyphenated name was judged as more caring, more dependent, less intelligent, more emotional, less competent, and less ambitious in comparison with a woman who kept her own name. A woman with her own name, on the other hand, was judged as less caring, more independent, more ambitious, more intelligent, and more competent, which was similar to an unmarried woman living together or a man.

Finally, a job applicant who took her partner’s name, in comparison with one with her own name, was less likely to be hired for a job and her monthly salary was estimated $1,250 lower (calculated to a working life, $500,000).

{ Basic and Applied Social Psychology | Continue reading | via The Jury Room }

‘Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life.’ –Wittgenstein

The first clear statement of relativism comes with the Sophist Protagoras, as quoted by Plato, “The way things appear to me, in that way they exist for me; and the way things appears to you, in that way they exist for you” (Theaetetus 152a). Thus, however I see things, that is actually true — for me. If you see things differently, then that is true — for you. There is no separate or objective truth apart from how each individual happens to see things. Consequently, Protagoras says that there is no such thing as falsehood.

Unfortunately, this would make Protagoras’s own profession meaningless, since his business is to teach people how to persuade others of their own beliefs. It would be strange to tell others that what they believe is true but that they should accept what you say nevertheless. So Protagoras qualified his doctrine: while whatever anyone believes is true, things that some people believe may be better than what others believe. (…)

Protagoras’s own way out that his view must be “better” doesn’t make any sense either: better than what? Better than opposing views? But there are no opposing views, by relativism’s own principle. And even if we can identify opposing views — taking contradiction and falsehood seriously — what is “better” supposed to mean? Saying that one thing is “better” than another is always going to involve some claim about what is actually good, desirable, worthy, beneficial, etc. What is “better” is supposed to produce more of what is a good, desirable, worthy, beneficial, etc.; but no such claims make any sense unless it is claimed that the views expressed about what is actually good, desirable, worthy, beneficial, etc. are true. If the claims about value are not supposed to be true, then it makes no difference what the claims are: they cannot exclude their opposites. (…)

Relativism turns up in many guises. Generally, we can distinguish cognitive relativism, which is about all kinds of knowledge, from moral relativism, which is just about matters of value. Protagoras’s principle is one of cognitive relativism. (…)

Another modern kind of cognitive relativism is linguistic relativism, that truth is created by the grammar and semantic system of particular language. This idea in philosophy comes from Ludwig Wittgenstein, but it turns up independently in linguistics in the theory of Benjamin Lee Whorf. On this view the world really has no structure of its own, but that structure is entirely imposed by the structure of language. Learning a different language thus means in effect creating a new world, where absolutely everything can be completely different from the world as we know it. Wittgenstein called the rules established by a particular language a “game” that we play as we speak the language. (…)

In linguistics, Whorf’s theory has mostly been superseded by the views of Noam Chomsky that there are “linguistic universals,” i.e. structures that are common to all languages. That would mean that even if language creates reality, reality is going to contain certain universal constants. In philosophy, on the other hand, Wittgenstein is still regarded by many as the greatest philosopher of the 20th century. But his theory cannot avoid stumbling into an obvious breach of self-referential consistency, for the nature of language would clearly be part of the structure of the world that is supposedly created by the structure of language. Wittgenstein’s theory is just a theory about the nature of language, and as such it is merely the creation of his own language game. We don’t have to play his language game if we don’t want to. By his own principles, we can play a language game where the world has an independent structure, and whatever we say will be just as true as whatever Wittgenstein says. Thus, like every kind of relativism, Wittgenstein’s theory cannot protect itself from its own contradiction. Nor can it avoid giving the impression of claiming for itself the very quality, objective truth, that it denies exists.

I went lickety-splickly, out to my old ‘55, pulled away slowly, feeling so holy

There’s one prediction about driverless cars that I can make with confidence: If millions of them ever roam the public highways, they will be far safer than cars driven by people. My confidence in this assertion does not derive from mere faith in technology. It’s just that if robotic drivers were as dangerous as human ones, then computer-controlled cars would never be allowed on the roads. We hold our machines to a higher standard than ourselves.

Over the past decade, the number of auto accidents in the United States—counting only those serious enough to be reported to the police—has been running at about six million a year. Those accidents kill about 40,000 people and injure well over two million more. Estimates of the economic impact are in the neighborhood of $200 billion. Much of that cost is shared among car owners through premiums for auto insurance.

This safety record certainly leaves ample room for improvement. An appropriate goal for automated vehicles might be to reduce highway carnage to the same order of magnitude experienced in other modes of transport, such as railroads and commercial aviation. That would mean bringing road fatalities down to roughly 1 percent of their current level—from 40,000 deaths per year to 400. (In terms of deaths per passenger mile, cars would then be the safest of all vehicles.)

And these ways wend they. And those ways went they.

What would happen if the world stop spinning? (…)

Although the Earth isn’t likely to stop spinning any time soon, its has slowed considerably since its formation.

Because gravity is strongest at the poles, and the Earth bulges at the equator by about 21.4 kilometers (due to the Earth’s rotation), if the Earth were to stop spinning, water would move from the equatorial regions toward the poles. The low-lying areas of northern Europe, Asia and North America would be covered by ocean. Land currently covered by sea around the equator, however, would become dry land, forming a massive equatorial continent.

In the house of breathings lies that world

The Misconception: You celebrate diversity and respect others’ points of view.

The Truth: You are driven to create and form groups and then believe others are wrong just because they are others.

Do you know she was calling bakvandets sals from all around, nyumba noo, chamba choo, to go in till him, her erring cheef, and tickle the pontiff aisy-oisy?

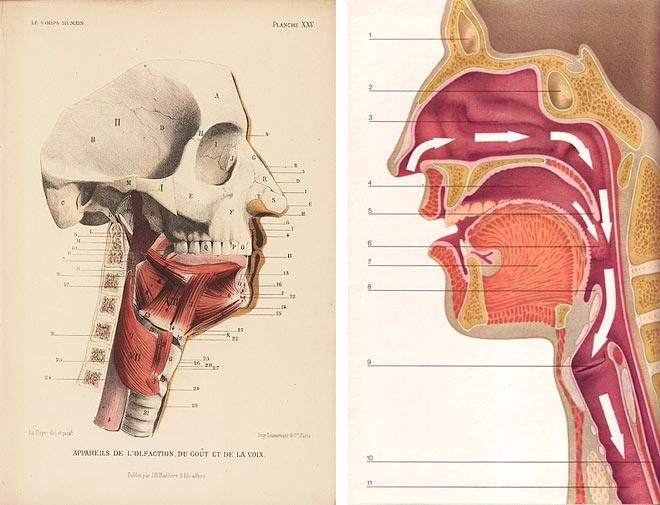

The notion that our body odors are potent, chemically charged mating signals—so-called pheromones—is so pervasive in women’s magazines and websites, you would think that all you need is one good sweat to lure your guy.

If only it were so. Pheromones, in scientific parlance, are aromatic chemicals emitted by one member of a species that affect another member of the same species, either by altering its hormones or by compelling it to change its behavior. When they work, they are truly bewitching. For instance, when a female silkworm moth wants to get her guy, she sprays a chemical called bombykol from her abdominal gland and her targeted male transforms into a sex slave, trailing the scent until he mounts her. It’s an enviable feat. Still, it’s a big leap to extrapolate from bugs to people—or even to lab mice, for that matter. No scientific study has ever proven conclusively that mammals have pheromones.

And a rainbow after long storms

All of us, at times, ruminate or brood on a problem in order to make the best possible decision in a complex situation. But sometimes, rumination becomes unproductive or even detrimental to making good life choices. Such is the case in depression, where non-productive ruminations are a common and distressing symptom of the disorder. In fact, individuals suffering from depression often ruminate about being depressed. This ruminative thinking can be either passive and maladaptive (i.e., worrying) or active and solution-focused (i.e., coping). New research by Stanford University researchers provides insights into how these types of rumination are represented in the brains of depressed persons.

photo { Erwin Blumenfeld }

A gentleman, hereinafter called the purchaser

I thought the purpose of patents was to spur innovation by giving people who invent something the exclusive use of their innovation for a limited time.

There’s still some of that. But out in Silicon Valley, patents have become the competitive weapon of choice, used by high-tech giants to bludgeon rivals and crush upstarts.

It turns out that the more patents you have, the more likely it is that you can extort exorbitant royalties from people who might have easily come up with the same idea or the same feature that you did but never thought to patent it. And the more patents you have, the more your competitor wants so he can retaliate with a patent suit of his own, claiming that it was you who stole the ideas from him.

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune

Academics like me are skilled users of turnitin.com. Never heard of it? Ask the nearest undergraduate and watch their cheek blanch. Turnitin is the trade’s leading ‘plagiarism detector’. You upload the student’s essay or dissertation and it’s checked against trillions of words and phrases in seconds. (…)

Take, for example, the indisputably most famous and quoted line in English literature, ‘To be, or not to be, that is the question’. Most theatregoers would think the sentence spit new. But should they also go to a performance of Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus they would hear the following in the hero’s magnificent opening soliloquy, in which he resolves to sell his soul: ‘Bid Oncaymæon farewell, Galen come’. The Greek Oncaymæon transliterates as ‘being and not being’.

‘To be or not to be’ is not a deeply original thought but a hackneyed sophomoric seminar topic. Hamlet is not thinking, he’s quoting. (…)

Voltaire did not apparently say ‘I may not agree with what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it’. As Morson says, ‘the statement belongs to a biographer of Voltaire’. It is what he would have said - utterly Voltairean, but not ipsissima verba.

oil on oak panel { Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Three Soldiers, 1568 }

Inventors of figures and phantoms shall they be in their hostilities

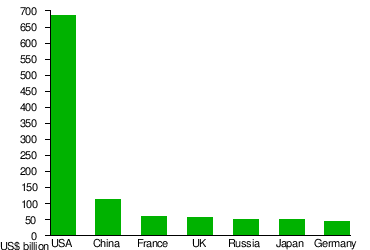

{ List of countries by military expenditures | Thanks JLB }

What, no DEVIL dogs? This dessert truck is bullshit.

Sorbonne in Paris, France, on 8 August 1900 (…) David Hilbert’s address set the mathematical agenda for the 20th century. It crystallised into a list of 23 crucial unanswered questions, including how to pack spheres to make best use of the available space, and whether the Riemann hypothesis, which concerns how the prime numbers are distributed, is true.

Today many of these problems have been resolved, sphere-packing among them. Others, such as the Riemann hypothesis, have seen little or no progress. But the first item on Hilbert’s list stands out for the sheer oddness of the answer supplied by generations of mathematicians since: that mathematics is simply not equipped to provide an answer.

This curiously intractable riddle is known as the continuum hypothesis, and it concerns that most enigmatic quantity, infinity. Now, 140 years after the problem was formulated, a respected US mathematician believes he has cracked it. What’s more, he claims to have arrived at the solution not by using mathematics as we know it, but by building a new, radically stronger logical structure: a structure he dubs “ultimate L”.

artwork { Jean-Michel Basquiat, Flexible, 1984 }

Yes I think he made them a bit firmer sucking them like that so long

If you’re not familiar with the law of diminishing returns, it states that at a certain point adding more effort will not produce significantly more gains. The challenge is knowing when you’ve reached that point.

For many managers this is an important question: How far do I keep going on a project before I declare that it’s “good enough” — and that further effort will not significantly change the outcome?

From my experience, there are two often-unconscious reasons for this unproductive quest for perfection. The first is the fear of failing. (…) The second is the anxiety about taking action.

Devil a much, says I. There is a bloody big foxy thief beyond by the garrison church at the corner of Chicken Lane.

Boys are maturing physically earlier than ever before. The age of sexual maturity has been decreasing by about 2.5 months each decade at least since the middle of the 18th century. Joshua Goldstein, director of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, has used mortality data to prove this trend, which until now was difficult to decipher. What had already been established for girls now seems to also be true for boys: the time period during which young people are sexually mature but socially not yet considered adults is expanding.

Come around to Barney Kiernan’s, says Joe. I want to see the citizen.

At their most fundamental level, brains are made up of neurons. And those neurons collectively comprise the two main types of brain tissue: white matter is made up primarily of axons, and grey matter is made up of synapses, or the connections between neurons.

Grey matter exists as a thin, relatively flat sheet covering the rest of the brain, and is referred to as the cortex. When you compare the brains of different mammal species, you find that certain measurements of brain structure scale in similar ways. In other words, variables like grey matter volume, total number of synapses, white matter volume, number of neurons, surface area, axon diameter, and number of distinct cortical “areas” maintain common mathematical relationships with each other, whether you’re looking at the brains of mice, rabbits, dogs, cats, hyenas, kangaroos, bats, sloths, bonobos, or humans. (…)

Lots of networks have been compared to urban systems. (…) To what extent, though, might a brain be like a city? There’s the obvious analogy: neurons are like highways. Neurons are channels that carry information in the form of electric signals from one location within the brain to another, while highways are channels that transport people and materials from one location within a city to another. Cognitive scientists Mark Changizi and Marc Destefano think that the analogy goes deeper. (…) They argue that the organization of city highway networks is driven over time by political and economic forces, rather than explicitly planned based on principles of highway engineering – which means that city highway systems may be subject to a form of selection pressure similar to the selection pressure exerted on biological systems.

photo { Keith Davis }

Another day wastes away, and my heart sinks with the sun

It wasn’t so long ago we thought space and time were the absolute and unchanging scaffolding of the universe. Then along came Albert Einstein, who showed that different observers can disagree about the length of objects and the timing of events. His theory of relativity unified space and time into a single entity - space-time. It meant the way we thought about the fabric of reality would never be the same again.

But did Einstein’s revolution go far enough? Physicist Lee Smolin at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, doesn’t think so. He and a trio of colleagues are aiming to take relativity to a whole new level, and they have space-time in their sights. They say we need to forget about the home Einstein invented for us: we live instead in a place called phase space.

If this radical claim is true, it could solve a troubling paradox about black holes that has stumped physicists for decades. What’s more, it could set them on the path towards their heart’s desire: a “theory of everything” that will finally unite general relativity and quantum mechanics.