But all things excellent are as difficult as they are rare

New support for the value of fiction is arriving from an unexpected quarter: neuroscience.

Brain scans are revealing what happens in our heads when we read a detailed description, an evocative metaphor or an emotional exchange between characters. Stories, this research is showing, stimulate the brain and even change how we act in life.

Researchers have long known that the “classical” language regions, like Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area, are involved in how the brain interprets written words. What scientists have come to realize in the last few years is that narratives activate many other parts of our brains as well, suggesting why the experience of reading can feel so alive. Words like “lavender,” “cinnamon” and “soap,” for example, elicit a response not only from the language-processing areas of our brains, but also those devoted to dealing with smells. (…)

Researchers have discovered that words describing motion also stimulate regions of the brain distinct from language-processing areas. (…)

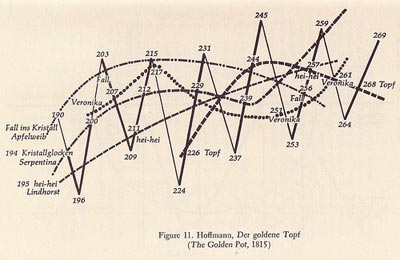

The brain, it seems, does not make much of a distinction between reading about an experience and encountering it in real life; in each case, the same neurological regions are stimulated. (…) Fiction — with its redolent details, imaginative metaphors and attentive descriptions of people and their actions — offers an especially rich replica. Indeed, in one respect novels go beyond simulating reality to give readers an experience unavailable off the page: the opportunity to enter fully into other people’s thoughts and feelings. (…) Scientists call this capacity of the brain to construct a map of other people’s intentions “theory of mind.” Narratives offer a unique opportunity to engage this capacity, as we identify with characters’ longings and frustrations, guess at their hidden motives and track their encounters with friends and enemies, neighbors and lovers. (…)

Reading great literature, it has long been averred, enlarges and improves us as human beings. Brain science shows this claim is truer than we imagined.