law

How did we end up with a drinking age of 21 in the first place?

In short, we ended up with a national minimum age of 21 because of the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984. This law basically told states that they had to enact a minimum drinking age of 21 or lose up to ten percent of their federal highway funding. Since that’s serious coin, the states jumped into line fairly quickly. Interestingly, this law doesn’t prohibit drinking per se; it merely cajoles states to outlaw purchase and public possession by people under 21. Exceptions include possession (and presumably drinking) for religious practices, while in the company of parents, spouses, or guardians who are over 21, medical uses, and during the course of legal employment.

{ Mental Floss | Continue reading }

photo { Miss Aniela }

U.S., food, drinks, restaurants, kids, law | February 9th, 2012 7:00 pm

The email might contain “privileged, confidential and/or proprietary information,” they are told. If it landed in their inbox by error, they are strictly prohibited from “any use, distribution, copying or disclosure to another person.” And in such case, “you should destroy this message and kindly notify the sender by reply email.” (…)

Email disclaimers, those wordy notices at the end of emails from lawyers, bankers, analysts, consultants, publicists, tax advisers and even government employees, have become ubiquitous—so much so that many recipients, and even senders, are questioning their purpose. (…)

Emails often now include automatic digital signatures with a sender’s contact information or witty sayings, pleas to save trees and not print them, fancy logos and apologies for grammatical errors spawned by using a touch screen. (…)

Some lawyers say the disclaimers have value, alerting someone who receives confidential, proprietary, or legally privileged information by accident that they don’t have permission to take advantage of it.

Others, including lawyers whose email messages are laden with them, say the disclaimers are for the most part unenforceable. They argue that they don’t create any kind of a contract between sender and recipient merely because they land in the recipient’s inbox.

It’s largely untested whether email disclaimers can hold up in court and at least one ruling on the matter was mixed.

Boilerplate language attached to every email dilutes the intention, some say. For instance, when every message from a sender’s account is tagged with “privileged and confidential,” it might make it difficult to convince a judge that any one email is more private than another.

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

law, technology | January 27th, 2012 9:20 am

Marriage as Punishment

Popular discourse portrays marriage as a source of innumerable public and private benefits, happiness, companionship, financial security, and even good health. Complementing this view, our legal discourse frames the right to marry as a right of access, the exercise of which is an act of autonomy and free will.

However, a closer look at marriage’s past reveals a more complicated portrait. Marriage has been used - and importantly, continues to be used - as state-imposed sexual discipline.

Until the mid-twentieth century, marriage played an important role in the crime of seduction. Enacted in a majority of U.S. jurisdictions in the nineteenth century, seduction statutes punished those who ’seduced and had sexual intercourse with an unmarried female of previously chaste character’ under a ‘promise of marriage.’ Seduction statutes routinely prescribed a bar to prosecution for the offense: marriage. The defendant could simply marry the victim and avoid liability for the crime. However, marriage did more than serve as a bar to prosecution. It also was understood as a punishment for the crime. Just as incarceration promoted the internalization of discipline and reform of the inmate, marriage’s attendant legal and social obligations imposed upon defendant and victim a new disciplined identity, transforming them from sexual outlaws into in-laws.

{ Melissa E. Murray/SSRN | Continue reading }

ideas, law, relationships | January 22nd, 2012 3:36 pm

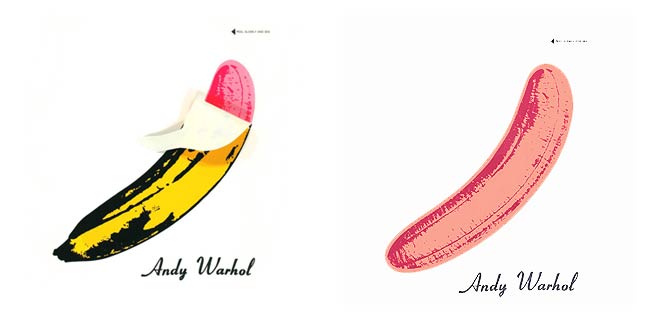

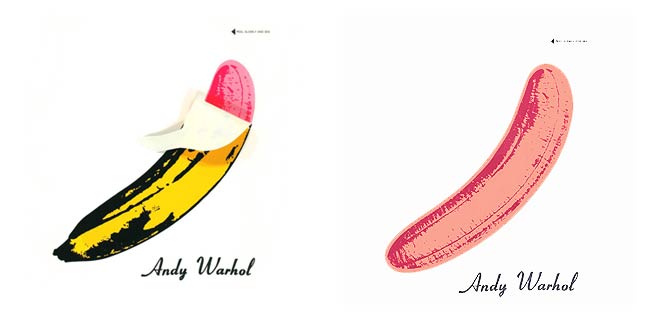

The Velvet Underground sued the Andy Warhol Foundation, accusing it of infringing the trademark for the banana design on the cover of the rock group’s first album in 1967.

The band’s founders, Lou Reed and John Cale, said that the foundation infringed the design by licensing it to third parties, according to the complaint filed yesterday in federal court in Manhattan.

The band, which was active from about 1965 to 1972, formed an artistic collaboration with Warhol, who designed the banana illustration for “The Velvet Underground and Nico,” which critics have labeled one of the most influential rock recordings of all time, according to the complaint.

The Warhol Foundation claimed it has a copyright interest in the design, according to the lawsuit. The Velvet Underground partnership said in the complaint that the design can’t be copyrighted because the banana image Warhol furnished for the illustration came from an advertisement and was in the public domain.

Warhol’s copyrighted works have a market value of $120 million and the foundation has earned more than $2.5 million a year licensing rights to those works, according to the complaint.

The Velvet Underground is seeking a judicial declaration that the foundation has no copyright to the banana design, an injunction barring the use of any merchandise using the artwork and monetary damages. The group is requesting a jury trial.

{ Bloomberg | Courthouse News Service }

economics, law, music, warhol | January 12th, 2012 11:27 am

US Congressman and poor-toupee-color-chooser Lamar Smith is the guy who authored the Stop Online Piracy Act. SOPA, as I’m sure you know, is the shady bill that will introduce way harsher penalties for companies and individuals caught violating copyright laws online (including making the unauthorized streaming of copyrighted content a crime which you could actually go to jail for). If the bill passes, it will destroy the internet and, ultimately, turn the world into Mad Max. (…)

This is a screenshot of Lamar’s site as it appeared on the 24th of July, 2011. (…) And this is the background image Lamar was using. I managed to track that picture back to DJ Schulte, the photographer who took it. Looks like someone forgot to credit him.

{ Vice | Continue reading }

law | January 12th, 2012 11:00 am

In its 1915 decision in Mutual Film v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, the Supreme Court held that motion pictures were, as a medium, unprotected by freedom of speech and press because they were mere “entertainment” and “spectacles” with a “capacity for evil.” Mutual legitimated an extensive regime of film censorship that existed until the 1950s. It was not until 1952, in Burstyn v. Wilson, that the Court declared motion pictures to be, like the traditional press, an important medium for the communication of ideas protected by the First Amendment. By the middle of the next decade, film censorship in the U.S. had been almost entirely abolished.

Why did the Court go from regarding the cinema as an unprotected medium to part of the constitutionally-protected “press”? The standard explanation for this shift is that civil libertarian developments in free speech jurisprudence in the 1930s and 40s made the changed First Amendment status of the movies and the fall of film censorship inevitable. Challenging this account, I argue that the shift was also the result of a dynamic I describe as the social convergence of mass communications. Social convergence takes place when the functions, practices, and cultures associated with different media come to resemble each other. By the 1950s, movies occupied a role in American culture that increasingly resembled the traditional press. At the same time, print journalism took on styles and functions that were like those historically associated with the movies. The demise of film censorship reflected not only more capacious understandings of freedom of expression, but also convergent communications. The article focuses on the efforts of a nationwide anticensorship movement, between 1915 and the 1950s, to engineer the reversal of Mutual using an argument based on media convergence.

This significant, lost chapter in the history of modern free speech has much to tell us about the ongoing relationship between the First Amendment and new media. It illustrates how courts and the public in an earlier time dealt with a question that is still pressing today: should the medium of communication have significance for free speech law? Illuminating historical patterns of judicial responses to new media, the work offers insights into what we may predict about the regulation of mass media in our own era of media convergence.

{ Samantha Barbas/SSRN | Continue reading }

law, media, showbiz | January 8th, 2012 12:04 pm

He is one of New York’s busiest casting directors, yet very few know of his work. (…)

For some 15 years, Mr. Weston has been providing the New York Police Department with “fillers” — the five decoys who accompany the suspect in police lineups.

Detectives often find fillers on their own, combing homeless shelters and street corners for willing participants. In a pinch, police officers can shed their uniforms and fill in. But in the Bronx, detectives often pay Mr. Weston $10 to find fillers for them.

A short man with a pencil-thin beard, Mr. Weston seems a rather unlikely candidate for having a working relationship with the Police Department, even an informal one. He is frequently profane, talks of beating up anyone who crosses him, and spends quite a bit of his money on coconut-flavored liquor.

But Mr. Weston points out that he has never failed to produce lineups when asked, no matter what time of night. “I never say no to money,” he said.

Across the nation, police lineups are under a fresh round of legal scrutiny, as recent studies have suggested that mistaken identifications in lineups are a leading cause of wrongful convictions, and that witnesses can be steered toward selecting the suspect arrested by the police.

But for all the attention that lineups attract in legal circles, Mr. Weston’s role in finding lineup fillers is largely unknown. Few defense lawyers and prosecutors, though they spar over the admissibility of lineups in court, have heard of him.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

economics, law, new york | October 17th, 2011 1:48 pm

For most people, the term art crime invariably brings to mind images of daring museum break-ins, the theft of million-dollar paintings, and the stylish, sexy thieves who mastermind them.

In reality, high-value museum thefts are the exception rather than the rule. As retired FBI Art Crime Team Special Agent Bob Wittman recounts in his memoir, “art theft is rarely about the love of art or the cleverness of the crime, and the thief is rarely the Hollywood caricature. (…) Nearly all the art thieves I met in my career had one thing in common: brute greed. They stole for money, not beauty.”

{ Crime, Law and Social Change | Continue reading }

art, law, scams and heists | September 8th, 2011 10:21 am

Illegal markets differ from legal markets in many respects. Although illegal markets have economic significance and are of theoretical importance, they have been largely ignored by economic sociology. In this article we propose a categorization for illegal markets and highlight reasons why certain markets are outlawed. We perform a comprehensive review of the literature to characterize illegal markets along the three coordination problems of value creation, competition, and cooperation. The article concludes by appealing to economic sociology to strengthen research on illegal markets and by suggesting areas for future empirical research. (…)

Markets are arenas of regular voluntary exchange of goods or services for money under conditions of competition (Aspers/Beckert 2008). The exchange of goods or services does not constitute a market when the exchange takes place only very irregularly and when there is no competition either on the demand side or on the supply side. Markets are illegal when either the product itself, the exchange of it, or the way in which it is produced or sold violates legal stipulations. What makes a market illegal is therefore entirely dependent on a legal definition.

When a market is defined as illegal, the state declines the protection of property rights, does not define and enforce standards for product quality, and can prosecute the actors within it. Not every criminal economic activity constitutes an illegal market; the product or service demanded may be too specific for competition to emerge, or it may simply be business fraud. Since illegality is defined by law, what constitutes an illegal market differs between legal jurisdictions and over time.

{ Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies | Continue reading | PDF }

Linguistics, economics, law | July 25th, 2011 9:07 am

U.S., halves-pairs, housing, law | July 19th, 2011 7:45 pm

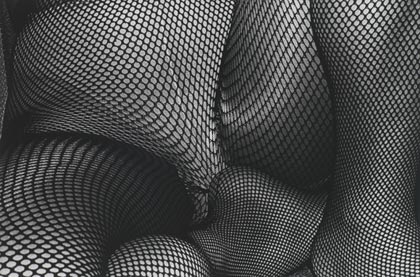

Is Pole Dancing Art? Court Rules No.

Nite Moves, a Latham, New York-based adult dancing club that features pole- and couch-dancing, had been seeking to argue that erotic dances counted as “dramatic or musical arts performances,” thereby qualifying for a tax exemption. A Tribunal had rejected that claim.

This means that Nite Moves must pay up on a $125,000 tax bill dating back to 2005 — though the club is appealing the ruling. (…)

To distinguish erotic dancing from, say, ballet, the court finds that real art requires you to go to school. In other words, stripping — or at least, the stripping that goes down at Nite Moves — doesn’t count as art because anyone can do it.

{ Art Info | Continue reading }

photo { Shomei Tomatsu }

U.S., dance, economics, law, leisure | June 15th, 2011 4:05 pm

The intentional torts of trespass against land and chattels, and the underlying property interests which they protect, are surely a foundation of any legal system that supports the private production of goods and services. The prevalence of these causes of action against theft—technically, involuntary transfers—even prior to the earliest development of common law legal systems supports this intuition.

But the trespass tort and its related causes of action presuppose a common set of normative expectations that identifies the set of goods to which the underling theft prohibition applies. If there were no widely obeyed norm against trespass of land and conversion of property, it would be exceedingly costly to enforce the formal laws against it, or in the absence of supplemental state enforcement, to undertake self-help measures to do so. That consensus may appear to be well-settled with respect to real property (my house) and most forms of tangible property (my car). That normative consensus tracks a positive consensus. Despite periodic intellectual fashions to the contrary, empirical evidence is clear that secure property rights are a critical ingredient in economic growth. (…)

However, any such consensus is often unsettled with respect to intangible goods—ideas and the various technologies and forms of expression in which those ideas are embodied—and, especially, to the set of creative goods protected by copyright. There are more than a handful of serious commentators who refuse to extend, or decline to presumptively extend, the empirically-grounded logic behind property rights in land and tangible assets to property rights in ideas, forms of expression and other intangible assets.

{ Jonathan M. Barnett, What’s So Bad About Stealing? | SSRN | Continue reading }

photo { Doug DuBois }

ideas, law, photogs | May 20th, 2011 10:38 pm

In a notification sent to all service providers and hosting companies in Turkey on Thursday (28 April), the Telecommunication Communication Presidency (TİB) forwarded a list of banned words and terms. (…)

[Some of the banned words:] Adrianne, Animal, Sister-in-law, Blond, Beat, Enlarger, Nude, Crispy, Escort, Skirt, Fire, Girl, Free, Gay, Homemade, Liseli (’high school student’).

{ Bianet | Continue reading }

Linguistics, law | May 1st, 2011 7:00 pm

What is protected in the fashion world via the law and legislation, and what is not? Blakely: The main protection fashion designers have is over their trademark: their logo, their name. Source is protected; that’s why you hear about raids on pirates, who have made copies of Louis Vuitton bags, Canal St. in New York (NYC), Santee Alley in Los Angeles (LA). Have control of their name; have copyright protection of all the two-dimensional designs that go into the production of a garment. Textile design with a certain pattern–automatically qualify for copyright protection of that design. What they don’t own are any of the three-dimensional designs they end up creating. The stuff you see prancing out on a runway are actually up for grabs. Anybody can copy any aspects of any of those designs and get into no trouble with the law. Those designs are not particularly utilitarian–a word that comes up a lot in this industry–utilitarian stuff tends not to be protected legally. Something has to be considered a work of art in order to be considered for copyright protection. The courts decided long ago that they did not want any fashion designers owning such utilitarian designs as shirts, blouses, pants, belts, lapels. Don’t want somebody owning a monopoly–basically what a copyright gives you. (…)

Standard view would be: If I think my design is going to be copied, and copied quickly–which is what has happened to some extent because the copying ability better and the speed faster–then you’d think people would have less incentive to create new and better designs. That does not seem to be the case in the fashion industry. Why? Several reasons. One, from the beginning, copyright has both given artists an advantage and also taken something away. What it takes away from creators is access to other creative designs. Copyright holders may own what they have, but they cannot sample freely from others around them. Huge problem in the film and music industry. The fashion industry doesn’t suffer from this problem because every design that has ever been made is within a type of public domain. It is the raw material they can sample from to make their new work. Rich archive. The history of fashion, every hem length, every curved seam, every style is available to sample from. Not just stealing–sort of a curatorial responsibility. They are curating. Different gestures, different design elements from the past. Inevitably creating something new.

{ Johanna Blakley on Fashion and Intellectual Property | EconTalk | Continue reading }

photo { Bianca Jagger by Andy Warhol }

fashion, ideas, law | April 22nd, 2011 2:01 pm

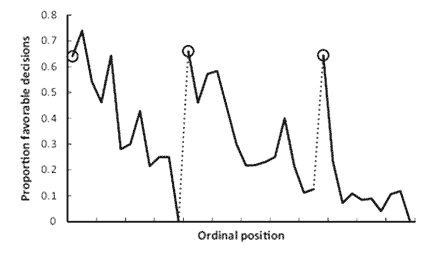

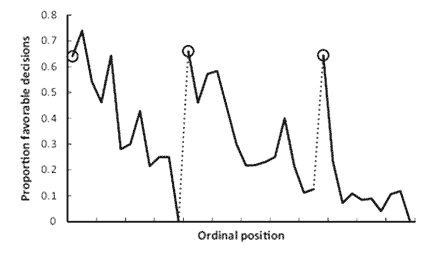

{ How food-breaks sway the decisions of judges. The graph above shows that the odds that prisoners will be successfully paroled start off fairly high at around 65% and quickly plummet to nothing over a few hours (although, see footnote). After the judges have returned from their breaks, the odds abruptly climb back up to 65%, before resuming their downward slide. | Discover | full story }

food, drinks, restaurants, law, psychology | April 12th, 2011 3:28 pm

Remember Paul Ceglia? He’s the fellow in upstate New York who sued Mark Zuckerberg last July, claiming that, way back in 2003, Zuckerberg had agreed to give him a 50% ownership in the project that became Facebook.

That claim seemed preposterous at the time, not least because Ceglia had waited 7 years to file it. And there was also the fact that Ceglia was a convicted felon, having been charged with criminal fraud in connection with a wood-pellet company he operated. (…)

But now Paul Ceglia has refiled his lawsuit. With a much larger law firm. And a lot more evidence. And the new evidence is startling.

{ Business Insider | Continue reading }

economics, law, social networks | April 12th, 2011 3:04 pm

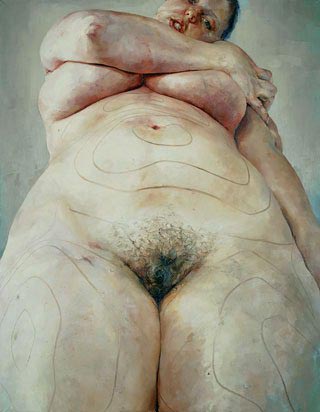

In a closely-watched oral argument Monday at a federal courthouse in Washington, the core questions of the case read like scripts from a college philosophy exam: are isolated human genes and the subsequent comparisons of their sequences patentable? Can one company own a monopoly on such genes without violating the rights of others? They are multi-billion dollar questions, the judicially-sanctioned answers to which will have enormous ramifications for the worlds of medicine, science, law, business, politics and religion.

Even the name of the case at the U.S. Circuit Court for the Federal Circuit — Association of Molecular Pathology, et al. v United States Patent and Trademark Office, et al — oozes significance. The appeals court judges have been asked to determine whether seven existing patents covering two genes — BRCA1 and BRCA2 (a/k/a “Breast Cancer Susceptibility Genes 1 and 2″) — are valid under federal law or, instead, fall under statutory exceptions that preclude from patentability what the law identifies as ”products of nature.”

In other words, no one can patent a human being. Not yet anyway.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

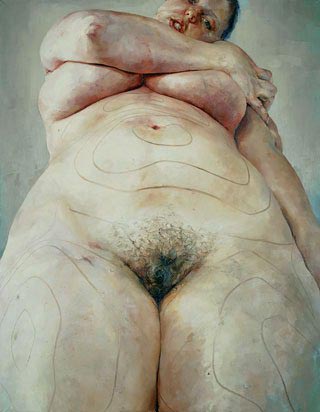

painting { Jenny Saville, Plan, 1993 }

economics, genes, law | April 6th, 2011 5:51 pm

In the 2006 movie, Borat: Cutural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, English comedian Sacha Baron Cohen plays the role of an outrageously inappropriate Kazakh television reporter who journeys across the United States to film a documentary about American culture. In the course of his travels, the title character uses his bizarre persona to elicit offensive statements and behavior from, as well as to generally humiliate, a number of ordinary Americans who are clearly not in on the joke. How did the producers convince these unfortunate stooges to participate in the project? According to several who later sued, the producers lied about the identity of Borat and the nature of the movie when setting up the encounters in advance over the telephone, and they then contradicted and disclaimed the lies in a waiver that the stooges signed without reading just before the cameras began to roll.

This talk article explains the doctrinal and normative reasons that the Borat problem, which arises frequently, although usually in more mundane contexts, divides courts. It then suggests an approach for courts to use when facing the problem that minimizes risks of exploitation and costs of contracting.

{ The ‘Borat’ Problem and the Law of Negotiation | Continue reading }

photo { Alpines, the Night Drive EP, 500 individually numbered 10″ Vinyl Discs }

ideas, law, showbiz | April 2nd, 2011 1:50 pm

A federal judge rejected Google’s $125 million class-action settlement with authors and publishers, delivering a blow to the company’s ambitious plan to build the world’s largest digital library and bookstore. (…)

The court’s decision throws into legal limbo one of Google’s most ambitious projects: a plan to digitize millions of books from libraries.

The Authors Guild and the Association of American Publishers sued Google in 2005 over its digitizing plans. After two years of painstaking negotiations, the authors and publishers devised with Google a sweeping settlement that would have helped to bring much of the publishing industry into the digital age.

The deal turned Google, the authors and the publishers into allies who defended the deal against an increasingly vocal chorus of opponents that included academics, copyright experts, the Justice Department and foreign governments. (…)

The deal would have allowed Google to make millions of out-of-print books broadly available online and to sell access to them, while giving authors and publishers new ways to earn money from digital copies of their works. Yet the deal faced a tidal wave of opposition from Google rivals like Amazon and Microsoft, as well as some academics, authors, legal scholars, states and foreign governments. The Justice Department opposed the deal, fearing that it would give Google a monopoly over millions of so-called orphan works, books whose right holders are unknown or cannot be found.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

books, economics, law, technology | March 22nd, 2011 7:00 pm

Shanghai is to extend the one-child policy to man’s best friend after tens of thousands of people complained of being bitten last year – and to prevent dog mess spoiling the country’s showcase business city.

The rule has already been imposed in several other Chinese cities, but Shanghai’s size – it has a population of more than 20 million – has made the presence of thousands of dogs more problematic. Dogs bigger than 3ft will be banned from the centre of the city and so-called “attack dogs”, including bulldogs, will be banned completely.

The ruling is the latest instance of uneasy relationships between man’s best friend and the Chinese authorities. During the Communist era of Mao Zedong, pets were frowned upon as a middle-class affectation and government opponents were condemned as capitalist running dogs. But China’s growing openness, combined with its rising affluence, means that pets are making a comeback, and there are around 100 million pet dogs in China. However, from May, a one-dog policy will be introduced in Shanghai and more than 600,000 unlicensed dogs will be declared illegal – and killed because of fears of rabies.

{ The Independent | Continue reading }

photo { Alvaro Sanchez-Montañes }

related { The special bond that often forms between people and both domesticated and wild animals may be, paradoxically, part of what makes us human. | Seed | full story }

asia, dogs, law | February 26th, 2011 7:18 pm