My last post said teen males want more sex than teen females. Older men also often complain of women withholding sex, while women complain of men demanding too much sex. From a typical top ten complaints list:

[Women About Men:] 3. They are not affectionate enough. 4. They tend to bypass sexual foreplay.

[Men About Women:] 1. Women complain, criticize and nag too much. … 4. They tend to withhold sex as a punishment or blackmail.

This is often explained in part via women just caring less about sex than men.

{ Overcoming Bias | Continue reading }

relationships, sex-oriented |

December 1st, 2010

Stuxnet is an incredibly advanced, undetectable computer worm that took years to construct and was designed to jump from computer to computer until it found the specific, protected control system that it aimed to destroy: Iran’s nuclear enrichment program.

Intelligence agencies, computer security companies and the nuclear industry have been trying to analyze the worm since it was discovered in June by a Belarus-based company that was doing business in Iran. And what they’ve all found, says Sean McGurk, the Homeland Security Department’s acting director of national cyber security and communications integration, is a “game changer.”

The construction of the worm was so advanced, it was “like the arrival of an F-35 into a World War I battlefield,” says Ralph Langner, the computer expert who was the first to sound the alarm about Stuxnet. (…)

The target was seemingly impenetrable; for security reasons, it lay several stories underground and was not connected to the World Wide Web. And that meant Stuxnet had to act as sort of a computer cruise missile: As it made its passage through a set of unconnected computers, it had to grow and adapt to security measures and other changes until it reached one that could bring it into the nuclear facility.

When it ultimately found its target, it would have to secretly manipulate it until it was so compromised it ceased normal functions.

And finally, after the job was done, the worm would have to destroy itself without leaving a trace.

Here’s how it worked, according to experts who have examined the worm:

–The nuclear facility in Iran runs an “air gap” security system, meaning it has no connections to the Web, making it secure from outside penetration. Stuxnet was designed and sent into the area around Iran’s Natanz nuclear power plant — just how may never be known — to infect a number of computers on the assumption that someone working in the plant would take work home on a flash drive, acquire the worm and then bring it back to the plant.

{ Fox News | Continue reading | Thanks Cole! }

mystery and paranormal, technology |

December 1st, 2010

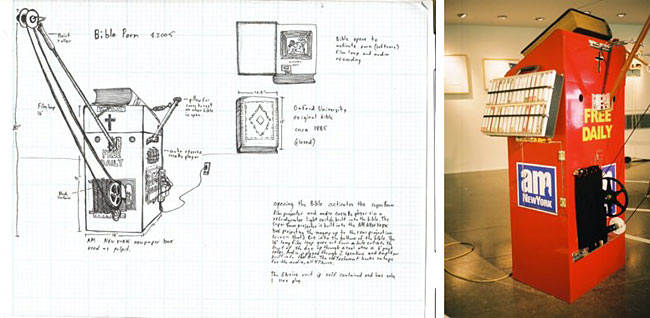

{ Patricia Piccinini }

unrelated { San Francisco bans Happy Meals. The city’s board of supervisors votes to forbid restaurants from giving away toys with meals that have high levels of calories, sugar and fat. | LA Times | full story }

food, drinks, restaurants, visual design |

December 1st, 2010

animals, photogs |

December 1st, 2010

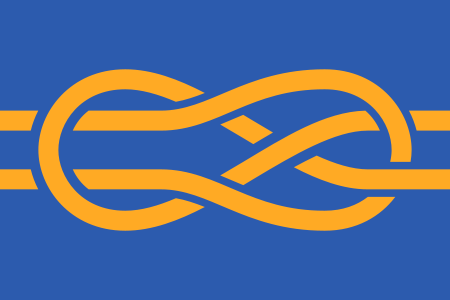

{ Flag of the International Federation of Vexillological Associations. | Vexillology is the scholarly study of flags. The Latin word vexillum means “flag.” The term was coined in 1957 by the American scholar Whitney Smith. It was originally considered a sub-discipline of heraldry. It is sometimes considered a branch of semiotics. | Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Linguistics, visual design |

December 1st, 2010

Murder followed by suicide is not an uncommon event, and several research reports have appeared on the topic. For example, Palermo, et al. (1997) found that typical murder-suicide in the Midwest of America was a white man, murdering a spouse, with a gun in the home. In England, Milroy (1993) reported that 5% to 10% of murderers committed suicide. Most were men killing spouses, with men killing children second in frequency. Shooting was the most common method. Similar patterns have been observed in Canada and Japan.

Mass murder has become quite common in recent years, from workers at post offices “going postal” to school children killing their peers in school. (…)

There are many categories of mass homicide, including familicides, terrorists, and those who simply “run amok.” (…)

Holmes and Holmes (1992) classified mass killers into five types: Disciples (killers following a charismatic leader), family annihilators (those killing their families), pseudocommandos (those acting like soldiers), disgruntled employees, and set-and-run killers (setting a death trap and leaving, such as poisoning food containers or over-the-counter medications).

It has been difficult to study several of these categories of mass murderers because no one has developed a comprehensive list of murderers falling into the groups. The only category studied hitherto has been the pseudocommandos (also known as rampage murders). (…)

The 98 incidents with a single perpetrator took place from 1949 to 1999, with 90% taking place in the period 1980-1999. (…) 56 of the killers were captured, 7 were killed by the police and one by a civilian, and 34 completed suicide at the time of the act (that is, within a few hours of the first killing and before capture). (…)

In contrast to mass murder, serial killers are defined as those who kill three or more victims over a period of at least thirty days (Lester, 1995). No study had appeared prior to 2008 on the extent to which serial killers complete suicide, but the informal impression gained from studying the cases (e.g., Lester, 1995) is that suicide is less common among them. However, occasional serial killers do complete suicide. (…)

Some serial killers commit suicide after being sent to prison. (…)

Some serial killers have made failed suicide attempts (e.g., Cary Stayner) before they embarked upon their serial killing. They appear to have turned their suicidal urges into murderous rampages.

{ Suicide in Mass Murderers and Serial Killers | Suicidology Online | Continue reading | PDF }

guns, horror, science |

November 30th, 2010

America remains the world’s richest large country. It’s generally estimated to have a per capita GDP level around $45,000, while the richest European nations manage only a $40,000 or so per capita GDP (setting aside low population, oil-rich states like Norway). Wealth underlies America’s sense of itself as a special country, and it’s also cited as evidence that America is better than other economies on a range of variables, from economic freedom to optimism to business savvy to work ethic.

But why exactly is America so rich? Karl Smith ventures an explanation:

I am going to go pretty conventional on this one and say a combination of three big factors

1. The Common Law

2. Massive Immigration

3. The Great Scientific Exodus during WWII

{ The Economist | Continue reading }

related { 5 Myths about the Fed }

photo { Young Kyu Yoo }

U.S., economics |

November 30th, 2010

A proposal to classify happiness as a psychiatric disorder.

It is proposed that happiness be classified as a psychiatric disorder and be included in future editions of the major diagnostic manuals under the new name: major affective disorder, pleasant type. In a review of the relevant literature it is shown that happiness is statistically abnormal, consists of a discrete cluster of symptoms, is associated with a range of cognitive abnormalities, and probably reflects the abnormal functioning of the central nervous system. One possible objection to this proposal remains–that happiness is not negatively valued. However, this objection is dismissed as scientifically irrelevant.

{ PubMed }

related { A startling proportion of the population, the existentially indifferent, demonstrates little concern for meaning in their lives. }

photo { Rob Hann }

psychology, science, theory |

November 30th, 2010

Here’s the official line on the prize from The Literary Review:

The Bad Sex Awards were inaugurated in 1993 in order to draw attention to, and hopefully discourage, poorly written, redundant or crude passages of a sexual nature in fiction. The intention is not to humiliate.

(…)

And Adam Ross also made the short list for the well-regarded novel “Mr. Peanut,” which includes:

“Love me!” she moaned lustily. “Oh, Ward! Love me now!”

He jumped out from his pajama pants so acrobatically it was like a stunt from Cirque du Soleil. But when he went to remove her slip, she said, “Leave it!” which turned him on even more. He buried his face into Hannah’s cunt like a wanderer who’d found water in the desert. She tasted like a hot biscuit flavored with pee.

{ New Yorker | Continue reading }

books, haha, sex-oriented |

November 30th, 2010

{ The Parrot AR.Drone was definitely one of the highlights of our day. How can you top a quadricopter that can fight with another using augmented reality, is easy to fly, and only needs an iPhone to control it? | Engadget | more photos + video }

kids, technology, toys |

November 30th, 2010

A new program enables a robot to detect whether another robot is susceptible to lies, and to use its gullibility against it by telling lies, researchers claim.

The robot could be capable of deceiving humans in a similar way, according to the scientists, based at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

{ The Guardian | Continue reading }

Scientists are trying to teach robots to read - so they can understand road signs and shop names to ‘live’ for themselves.

Experts believe developing literate artificial intelligence should be relatively simple because computers are already able to turn scanned books into text.

{ Daily Mail | Continue reading }

photo { Mark King }

psychology, robots & ai, technology |

November 30th, 2010

visual design |

November 30th, 2010

I scammed department stores and gyms and book chains. You’d be surprised how easy it was to lie — and get away. (…)

In those days, J.C. Penney had the loosest return policy. No receipt? No tags? No problem. They gave the item a once-over and found something comparable in quality to gauge the price. Most stores issued a gift card to a customer without any real evidence of purchase; J.C. Penney always gave cash. (…)

I must have pocketed $150 to $200 in books every month for the better part of a year. My biggest single score came when I discovered a dollar store that sold remainders. I bought a hardcover about Richard Nixon with a list price of $35, walked it to the bookstore and left with a gift card for the full amount. Then I went back to the dollar store and bought all eight remaining copies, returning them sporadically over the next year.

{ Jason Jellick/Salon | Continue reading }

experience, scams and heists |

November 30th, 2010

Is it OK to boil a lobster? (…)

Let’s consider the life, or rather the death, of a lobster. In nature lobsters begin very small and die a million horrible deaths in a million horrible ways. As they get older the death rate drops. We have ample evidence that lobsters do not go gentle into that good night, dying peacefully in their sleep at a ripe old age. Instead, once mature, a lobster that doesn’t go into the pot might face off with cod, flounder, an eel or two, or one of many diseases.

Considering that one of the natural deaths a lobster may face is to be torn limb from limb by an eel, getting tossed into a pot of boiling water doesn’t seem quite so gruesome. But there is a big difference between death by eel and death by human, the eel is not human. And now we have hit upon the broader question that must be answered before we can understand the short answer given above: Are humans a part of nature, or apart from nature?

{ The Science Creative Quaterly | Continue reading }

photo { Bill Owens }

animals, food, drinks, restaurants, ideas |

November 30th, 2010

In my column in Skeptical Inquirer (November/December 1996), I dealt with the major cases of alleged spontaneous human combustion (SHC) reported in Larry E. Arnold’s book Ablaze! The Mysterious Fires of Spontaneous Human Combustion (1995). (…)

Obviously, the Hess case had nothing to do with spontaneous human combustion, as Larry Arnold should have realized.

Arnold, who is not a physicist but a Pennsylvania school bus driver, had no justification for asking ominously, “Did Hess succumb to SHC?” The unburned clothing should have led any sensible investigator to one of the possibilities limited by that fact: for example, that Hess had been burned previously, or his skin injuries were caused by steam or hot water, chemical liquids or vapors, or some type of radiation (possibly even extreme sunburn through loosely woven clothing).

{ Skeptical Inquirer | COntinue reading }

If you’ve never started a fire in a fireplace (and no, those automatic electric fireplace don’t count), then this guide is for you.

1. Make sure your chimney is clean and free of blockages.

2. Open the damper.

3. Prime the flue.

4. Develop an ash bed.

5. Build an “upside down” fire.

…

{ The Art of Manliness | Continue reading }

fire, guide, incidents, weirdos |

November 30th, 2010

photogs |

November 30th, 2010

The euro zone’s debt crisis deepened on Tuesday as investors pushed the spreads on Spanish, Italian and Belgian bonds to euro lifetime highs and Portugal warned of “intolerable risks” facing its banks. (…)

Two days after the bloc approved an 85 billion euro ($111.7 billion) emergency aid package for Ireland, worries about contagion to Portugal and Spain persisted and the borrowing costs of large countries like Italy and France shot higher.

Markets are already discounting an eventual rescue of Portugal although the government in Lisbon denies, as Irish leaders initially did, that the country needs outside aid. (…)

Eurointelligence, an online commentary service, said markets were growing increasingly concerned about the solvency of euro zone peripheral states after focusing mainly on their short-term liquidity problems in past weeks.

“We at Eurointelligence consider a default of Greece, Ireland and Portugal a done deal,” they wrote on Tuesday. “The question is only now whether Spain can scrape through.”

{ Reuters | Continue reading }

related { The Eurozone Endgame: Four Scenarios }

economics |

November 30th, 2010

According to Slashdot and some awesome guy named Big Alan (AKA Alan Hirsch):

… the key to a man’s heart, and other parts, is pumpkin pie. Out of the 40 odors tested in Hirsch’s study, a mixture of lavender and pumpkin pie got the biggest rise out of men ages 18 to 64. That particular fragrance was found to increase penile blood flow by an average of 40%. “Maybe the odors acted to reduce anxiety. By reducing anxiety, it acted to remove inhibitions,” said Hirsch.

{ OmniBrain/ScienceBlogs | Continue reading }

photo { Young Kyu Yoo }

food, drinks, restaurants, olfaction, relationships, science, sex-oriented |

November 30th, 2010

The Ford Crown Victoria has long been the most widely used vehicle in New York City’s taxi fleet. But Ford is retiring the Crown Vic next year, and that means NYC needs to find a replacement.

Enter the Taxi of Tomorrow competition, a project created by city officials to find the next major taxi model.

So far, the city has narrowed the competition down to three finalists. The winner, which will be picked next year, will have an exclusive contract to provide the city with taxi cabs.

{ Fast Company | Continue reading }

In 2007, TLC’s Board of Commissioners approved a new package of taxi stickers. Smart Design, a design firm, produced and donated the new logo designs to TLC.

Taxi drivers and owners purchased the stickers from authorized printers.

The 4 stickers (per vehicle side) in the logo package were: a fare panel, the NYCTAXI sticker, the medallion number and a checker stripe decal.

{ NYC.gov | Continue reading }

new york, transportation, visual design, zzzzzzzzz |

November 30th, 2010