I understand about the food, Baby Bubba

Gamers, as video-game players are known, thrill to “the pull,” that mysterious ability that good games have of making you want to play them, and keep playing them.

Miyamoto’s games are widely considered to be among the greatest. He has been called the father of modern video games. The best known, and most influential, is Super Mario Bros., which débuted a quarter of a century ago and, depending on your point of view, created an industry or resuscitated a comatose one. It spawned dozens of sequels and spinoffs. Miyamoto has designed or overseen the development of many other blockbusters, among them the Legend of Zelda series, Star Fox, and Pikmin. Their success, in both commercial and cultural terms, suggests that he has a peerless feel for the pull, that he is a master of play—of its components and poetics—in the way that Walt Disney, to whom he is often compared, was of sentiment and wonder. (…)

What he hasn’t created is a company in his own name, or a vast fortune to go along with it. He is a salaryman. Miyamoto’s business card says that he is the senior managing director and the general manager of the entertainment-analysis and -development division at Nintendo Company Ltd., the video-game giant. What it does not say is that he is Nintendo’s guiding spirit, its meal ticket, and its playful public face. Miyamoto has said that his main job at Nintendo is ningen kougaku—human engineering. He has been at the company since 1977 and has worked for no other.

New new, New York, sittin’ here

Over the past decade the neighbourhood, which sits just over the East River from Manhattan, has been transformed from a sleepy, poor, residential area of Jewish, eastern European and Hispanic working-class immigrants to one where most denizens appear to have beards, piercings, lots of tattoos and belong to at least one band. Most also tend to write a blog and spend all night drinking or involved in art projects. Brooklyn’s Williamsburg becomes new front line of the gentrification battle.

Over the past decade the neighbourhood, which sits just over the East River from Manhattan, has been transformed from a sleepy, poor, residential area of Jewish, eastern European and Hispanic working-class immigrants to one where most denizens appear to have beards, piercings, lots of tattoos and belong to at least one band. Most also tend to write a blog and spend all night drinking or involved in art projects. Brooklyn’s Williamsburg becomes new front line of the gentrification battle.

Man Jumps In Front Of G Train After Stabbings. Man Crushed By #4 Train At Union Square Station.

Cops bust seven men playing chess in upper Manhattan park. Related: Why chess may be an ideal laboratory for investigating gender gaps in science and beyond.

Peter Plagens on the MoMA Abstract Expressionism Show.

Museum Revives Time Square’s Peep Show Past.

A posse ad esse

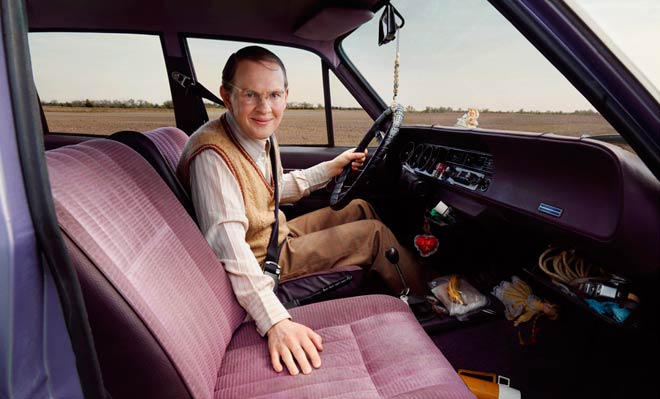

William James Sidis (1898-19444) showed astonishing intellectual qualities from an exceptionally early age. By the age of one he had learned to spell in English. He taught himself to type in French and German at four and by the age of six had added Russian, Hebrew, Turkish and Armenian to his repertoire. At five he devised a system which could enable him to name the day of the week on which any date in history fell. Hot-housed by his pushy father, Sidis entered Harvard at eleven, and was soon lecturing on 4 dimensional bodies to the University’s Maths Society.

At twelve he suffered his first nervous breakdown, but recovered at his father’s sanatorium, and after returning to Harvard, graduated with first class honours in 1914, aged just sixteen. Law School followed and by the age of twenty Sidis had become a professor of maths at Texas Rice Institute. (…)

Sidis was just 27 when he predicted the existence of what we now know as ‘black holes.’

{ Bookride | Continue reading }

In his adult years, it was estimated that he could speak more than forty languages, and learn a new language in a day. (…)

Sidis created a constructed language called Vendergood in his second book, entitled Book of Vendergood, which he wrote at the age of eight. The language was mostly based on Latin and Greek, but also drew on German and French and other Romance languages. (…)

Sidis was also a “peridromophile,” a term he coined for people fascinated with transportation research and streetcar systems.

{ Wikipedia }

photo { Aaron Feaver }

A replica of the universe

“The Library of Babel” is a short story by Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), conceiving of a universe in the form of a vast library containing all possible 410-page books of a certain format.

Borges’s narrator describes how his universe consists of an enormous expanse of interlocking hexagonal rooms, each of which contains the bare necessities for human survival—and four walls of bookshelves. Though the order and content of the books is random and apparently completely meaningless, the inhabitants believe that the books contain every possible ordering of just a few basic characters (letters, spaces and punctuation marks). Though the majority of the books in this universe are pure gibberish, the library also must contain, somewhere, every coherent book ever written, or that might ever be written, and every possible permutation or slightly erroneous version of every one of those books. The narrator notes that the library must contain all useful information, including predictions of the future, biographies of any person, and translations of every book in all languages.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Helbing’s list of websites that are potential sources of data for an Earth Simulator (…)

Internet and historical snapshots

The Internet Archive / Wayback machine offers permanent access for researchers, historians, scholars, people with disabilities, and the general public to historical collections that exist in digital format. Founded in 1996, now the Internet Archive includes texts, audio, moving images, and software as well as archived

The Knowledge Centers is a collection of links to other resources for finding Web pages as they used to exist in the past.

Whenago provides quick access to historical information about what happened in the past on a given day.

(…)

Text mining on the Web

The Observatorium project focuses on complex network dynamics in the Internet, proposing to monitor its evolution in real-time, with the general objective of better understanding the processes of knowledge generation and opinion dynamics.

We Feel Fine is a database of several million human feelings, harvested from blogs and social pages in the Web. Using a series of playful interfaces, the feelings can be searched and sorted across a number of demographic slices. Web api available as well.

CyberEmotions focuses on the role of collective emotions in creating, forming and breaking-up ecommunities. It makes available for download three datasets containing news and comments from the BBC News forum, Digg and MySpace, only for academic research and only after the submission of an application form.

‘We are not provided with wisdom, we must discover it for ourselves, after a journey through the wilderness which no one else can take for us, an effort which no one can spare us.’ –Proust

What’s the best way to overcome depression? Antidepressant drugs, or Buddhist meditation?

A new trial has examined this question. The short answer is that 8 weeks of mindfulness mediation training was just as good as prolonged antidepressant treatment over 18 months. But like all clinical trials, there are some catches.

photo { David Stewart }

Hence this infinite fraternity of feeling

I like discussions, and when I am asked questions, I try to answer them. [But] I don’t like to get involved in polemics. If I open a book and see that the author is accusing an adversary of “infantile leftism” I shut it right away. That’s not my way of doing things. (…) A whole morality is at stake, the one that concerns the search for truth and the relation to the other. (…)

The polemicist proceeds encased in privileges that he possesses in advance and will never agree to question. On principle, he possesses rights authorizing him to wage war and making that struggle a just undertaking; the person he confronts is not a partner in search for the truth but an adversary, an enemy who is wrong, who is armful, and whose very existence constitutes a threat. For him, then the game consists not of recognizing this person as a subject having the right to speak but of abolishing him as interlocutor, from any possible dialogue; and his final objective will be not to come as close as possible to a difficult truth but to bring about the triumph of the just cause he has been manifestly upholding from the beginning. The polemicist relies on a legitimacy that his adversary is by definition denied.

{ Michel Foucault, interview conducted by Paul Rabinow, May 1984 | Continue reading }

photo { Tony Stamolis }

I said the macaroni’s sour, the peas all mushed, and the chicken tastes like wood

{ By the time David Hurlbut bought the Harmony Club, a 20,000-square-foot building on the waterfront here, it had been abandoned for nearly 40 years. Built in 1909 as a social club by a group of prominent Jewish businessmen, it had been turned into an Elks club in the 1930s; when the Elks disbanded in 1960, the building was boarded up. | NY Times | full story }

Well I’m imp the dimp, the ladie’s pimp

The FBI estimates that a mid-level trafficker can make more than $500,000 dollars a year by marketing just four girls.

Youth Radio obtained a hand-written business plan from a pimp. The business plan titled Keep It Pimpin states how the pimp wants to expand his trafficking business locally as well as nationally. He also writes that he wants to discover girls “from all over”–especially girls in jail houses and in small cities.

photo { Luke Stephenson }

And I’m big bad E and I’m everywhere, so just throw your hands up in the air

{ 1. Wai Lin Tse | 2. Jennilee Marigomen }

If the universe can be eternal into the future, is it possible that it is also eternal into the past? Here I will describe a recent theorem which shows, under plausible assumptions, that the answer to this question is no.

related { eternity, quarterly report R02, terminology | download PDF }

G-55 fly ma let’s go

The researchers in question looked at over 5,000 people, and were able to discern five different styles of flirting. (…)

Traditional.— This is based very much in traditional gender roles. You know, where the men make the first move, and women don’t pursue men. This means that women (who’re more passive) are less flattered by flirting, and also find it more difficult to get men’s attention. Men, on the other hand, tend to know women longer before approaching them. So, basically, all quite introverted.

Physical.— This is based very much on sexual attraction, and communicating that interest. Relationships formed as a result tend to be formed more quickly, and have greater emotional and sexual chemistry than some others.

Sincere.— This is all about, well, sincerity. So it focuses on the creation of emotional connections, and on demonstrating sincere interest in the other person. Women tend to score higher here, but both men and women think it’s a good way to go about things, and relationships tend to be meaningful, and have good chemistry.

Playful.— This is mostly flirting for the sake of flirting. People using this style tend not to have any interest in long-term/important relationships (and so tend not to), but do it because they find it fun and it enhances their self-esteem.

Polite.— This is very much about being proper and polite. While sexual flirting is, obviously, not high on the agenda, and people who use this style tend to approach those they like less often, they also tend to form meaningful relationships with people.

photo { Garry Winogrand, New York, 1969 }

In other words, we should not be fooled by etymology and think that theory is about Vorhandenheit and praxis about Zuhandenheit

Sex costs amazing amounts of time and energy. Just take birds of paradise touting their tails, stags jousting with their antlers or singles spending their weekends in loud and sweaty bars. Is sex really worth all the effort that we, sexual species, collectively put into it?

Most biologists think that sex is totally worth it. With sex, every new generation receives a fresh combination of genes from its parents. This makes it easier to adapt to changing environments, as genes can spread quickly through a population.

In asexual species every child will be genetically identical to its parents, making it hard to compensate for disadvantageous mutations. Biologists expect that deleterious mutations will pile up in asexual species in a process known as Muller’s ratchet. With every mutation in an asexual lineage, Muller’s ratchet clicks one step closer to extinction.

photo { Glenn Glasser }

In the mornin’ roll over and we can start over

Like to sleep around? Blame your genes.

People’s predilections for promiscuity lie partially in their DNA, according to a new study.

A particular version of a dopamine receptor gene called DRD4 is linked to people’s tendency toward both infidelity and uncommitted one-night stands, the researchers reported Nov. 30 in the online open-access journal PloS One.

The same gene has already been linked to alcoholism and gambling addiction, as well as less destructive thrills like a love of horror films. One study linked the gene to an openness to new social situations, which in turn correlated with political liberalism.

photo { Logan White }

Rattle big black bones in the danger zone

{ The US authorities have discovered 20 tonnes of marijuana, worth tens of millions of dollars, in one of the most advanced illegal tunnels ever found. The passage is half a mile long and runs from inside a house in Mexico straight under the border with the United States and into a warehouse in San Diego. | BBC | video }

Fifth Ave shit baby, Fendi furs

Well, you see, Whitaker introduces us to the notion of change. This is a very important concept in family therapy, and it grew out of work with people in relationships. I’m talking about the idea that therapy is not about insights. It’s about change. This makes sense. After all, when people come together to form a relationship, whether they realise it or not, they’re trying to change each other. All too often, though, they fall into a situation called homeostasis in which change is impossible. They are stuck in seemingly unchangeable patterns. So what you do? (…)

Who I am and who you are is pretty much a plaything of context and assumptions. Change the context, change the assumptions, and you change the self. Do that with people in a relationship, and you change the relationship.

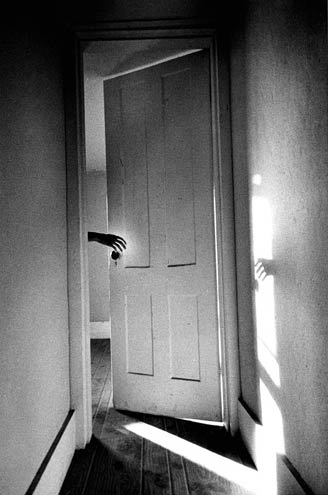

photo { Ralph Gibson, The Somnambulist, 1970 }

Diremood is the name is on the writing chap of the psalter

Other muscles can simulate a smile, but only the peculiar tango of the zygomatic major and the orbicularis oculi produces a genuine expression of positive emotion. Psychologists call this the “Duchenne smile,” and most consider it the sole indicator of true enjoyment. The name is a nod to French anatomist Guillaume Duchenne, who studied emotional expression by stimulating various facial muscles with electrical currents. (The technique hurt so much, it’s been said, that Duchenne performed some of his tests on the severed heads of executed criminals.)

In his 1862 book Mecanisme de la Physionomie Humaine, Duchenne wrote that the zygomatic major can be willed into action, but that only the “sweet emotions of the soul” force the orbicularis oculi to contract. “Its inertia, in smiling,” Duchenne wrote, “unmasks a false friend.”

Psychological scientists no longer study beheaded rogues — just graduate students, mainly — but they have advanced our understanding of smiles since Duchenne’s discoveries. We now know that genuine smiles may indeed reflect a “sweet soul.” The intensity of a true grin can predict marital happiness, personal well-being, and even longevity. We know that some smiles — Duchenne’s false friends — do not reflect enjoyment at all, but rather a wide range of emotions, including embarrassment, deceit, and grief. We know that variables (age, gender, culture, and social setting, among them) influence the frequency and character of a grin, and what purpose smiles play in the broader scheme of existence. In short, scientists have learned that one of humanity’s simplest expressions is beautifully complex.

‘Donc défaire la ressemblance ça a toujours appartenu à l’acte de peindre.’ –Deleuze

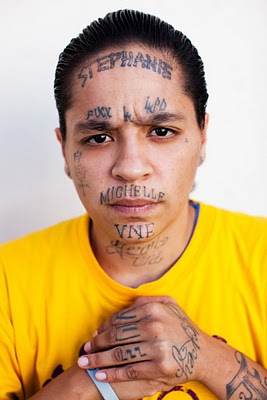

{ I came out the door the other day to find this girl sitting on my steps smoking a joint with a friend. She apologized for smoking there and I said there was no problem until there was a problem which she seemed to like. I told her I liked her tattoos and asked if I could take her picture. She seemed flattered. While photographing her I asked how the LAPD liked her tattoos and she said “Yeah…they like to photograph them too.” | Tracy photographed by Stephen Zeigler }

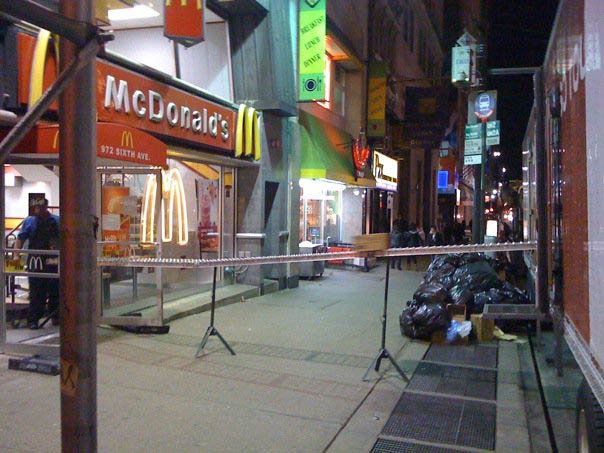

we own the night

{ the adventures of imp on 6th avenue, december 7, 2010, 11pm }