As I shall answer to gracious heaven, I’ll always in always remind of snappy new girters

Songs sound less sad when you’re older

Music is a powerful tool of expressing and inducing emotions. Lima and colleagues aimed at investigating whether and how emotion recognition in music changes as a function of ageing. Their study revealed that older participants showed decreased responses to music expressing negative emotions, while their perception of happy emotions remained stable.

Then you came along with your siren song

Albert Einstein is reported to have said that insanity consists of doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. By those standards, the deal with Greece that is about to be agreed looks insane. The only justification is that it is needed to play for time. This is a bad strategy. Something more radical is required.

The question about the prospects for Greece is not whether the country will default. That is, in my view, as near to a certainty as any such thing can be. The question is whether a default would be enough to return the economy to reasonable health. I strongly doubt it. The country seems too uncompetitive for that. A default is a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for a return to economic health.

painting { Andrew Wyeth, Wind From the Sea, 1947 }

If you want breakfast in bed, sleep in the kitchen

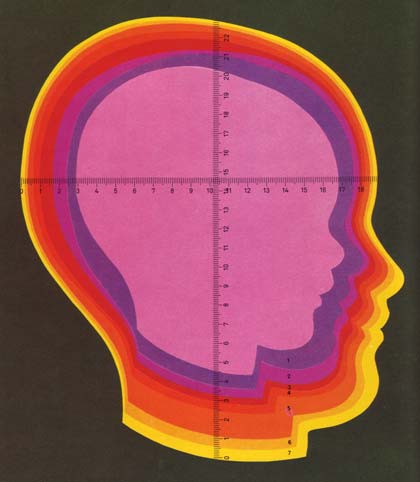

Where does psychological health end and mental illness begin? (…)

We are in the midst of a mental illness epidemic. Office visits by children and adolescents treated for the condition jumped forty-fold from 1994 to 2003. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, nearly half of all Americans have suffered from mental illness—depression, anxiety, even psychosis—at some time in their lives. Is one out of every two Americans mentally ill, or could it be that the system of psychiatric diagnosis too often mistakes the emotional problems of everyday life for psychopathology?

This system is codified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the official handbook of the American Psychiatric Association. Now in its fourth edition, the psychiatric bible, as it is sometimes called, spells out the criteria for over 360 different diagnoses. The DSM serves as the basic text for training practitioners, for insurance companies who rely on it to determine coverage, for social service agencies who use it to assess disabilities, and for the courts, which turn to it to resolve questions of criminal culpability, competence to stand trial, and insanity.

Despite the vast influence of DSM and the best efforts of its architects, the manual has failed to clear up the murky border between health and sickness.

‘From the cradle to the coffin underwear comes first.’ –Bertolt Brecht

The ad industry is quickly evolving into a new industry - one that won’t offer only the limited menu of services that’s attributed to it today. I’m not sure if this new industry should even be called advertising anymore, as the term itself can be an albatross to innovation. But whatever the name is, it’ll be even more exciting and productive than in its current incarnation.

When I invented the 4th Amendment Wear brand for my consultancy, I didn’t realize at the time that it would teach me such an important lesson about where we’re headed. (…)

It’s one thing to create an ad. It’s a whole other beast to invent new technology, create products using that technology, tap into social media, and orchestrate a marketing campaign to reach millions. (…)

While much of 4th Amendment Wear’s success can be attributed to the brand being in the right place at the right time, the truth is, all brands need to be.

{ Tim Geoghegan | Continue reading | 4th Amendment Wear picked up the Gold lion for Promo & Activation at Cannes. }

Heineken Star Player… (…) Whether this piece of work gets recognized at Cannes this week or not is not relevant or even important. What’s important is that it wasn’t the regular copywriter + art director duo who came up with the Idea. It was a combination of a Storyteller and a Software Developer who conceived it.

Good old world (Waltz)

Look at eggs. Today, a couple of workers can manage an egg-laying operation of almost a million chickens laying 240,000,000 eggs a year. How can two people pick up those eggs or feed those chickens or keep them healthy with medication? They can’t. The hen house does the work—it’s really smart. The two workers keep an eye on a highly mechanized, computerized process that would have been unimaginable 50 years ago.

But should we call this progress? In a sense it sounds like a deal with the devil. Replace workers with machines in the name of lower costs. Profits rise. Repeat. It’s a wonder unemployment is only 9.1%. Shouldn’t the economy put people ahead of profits?

Well, it does. The savings from higher productivity don’t just go to the owners of the textile factory or the mega hen house who now have lower costs of doing business. Lower costs don’t always mean higher profits. Or not for long. Those lower costs lead to lower prices as businesses compete with each other to appeal to consumers.

The result is a higher standard of living for consumers. (…)

Somehow, new jobs get created to replace the old ones. Despite losing millions of jobs to technology and to trade, even in a recession we have more total jobs than we did when the steel and auto and telephone and food industries had a lot more workers and a lot fewer machines.

I put a message in my music, hope it brightens your day

Long before we communicated with language, we communicated with our bodies, especially our faces. Everyone knows we ‘talk’ with facial expressions, but do we ‘hear’ ourselves with them?

{ Thoughts on Thoughts | Continue reading }

The Turing test is a test of a machine’s ability to exhibit intelligent behavior. A human judge engages in a natural language conversation with one human and one machine, each emulating human responses. All participants are separated from one another. If the judge cannot reliably tell the machine from the human, the machine is said to have passed the test.

images { 1 | 2. Trisha Donnelly }

There’s a Duster tryin’ to change my tune

Despite growing numbers of singles, the idealization of marriage and child rearing remains strong, pervasive, and largely unquestioned. Guided by life course perspective, the purpose of this article was to examine familial and societal messages women receive when not married by their late 20s to mid-30s. (…)

Women, when compared with men, experience more pronounced pressure to confirm to the “Standard North American Family” ideology and this may be especially true after 9/11, when mainstream messages strongly promoted tra- ditional ideologies of gender and families. Accepted notions of femininity remain based on women having a connection with a man to protect and care for her. Such constructions reflect Rich’s argument that “compulsory heterosexuality” is a controlling force in women’s lives. Compulsory heterosexuality positions the heterosexual romantic relationship within a patriarchal context as natural, normative, and the most desirable of all relationships. Furthermore, the dic- tate of motherhood and the coupling of marriage and motherhood further encourage women to enter into marriage.

Despite such ideologies, increasing proportions of women are single, with 41% of women aged 25 to 29 years and 24% of women aged 30 to 34 years having never married (U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2007).

related { Psychologists find link between ovulation and women’s ability to identify heterosexual men }

photo { Alonzo Jordan }

‘If two contrary actions be started in the same subject, a change must necessarily take place, either in both, or in one of the two, and continue until they cease to be contrary.’ –Spinoza

Scientists have traced chronic pain to a defect in one enzyme in a single region of the brain. Could this be a decisive turn in the battle against pain? (…)

As neuroscientists learn more about the biological basis of pain, the situation is finally beginning to change. Most remarkably, unfolding research shows that chronic pain can cause concrete, physiological changes in the brain. After several months of chronic pain, a person’s brain begins to shrink. The longer people suffer, the more gray matter they lose. (…)

Normally, pain is triggered by a set of danger-sensing neurons, called nociceptors, that extend into the organs, muscles, and skin. Different types of nociceptors respond to different stimuli, including heat, cold, pressure, inflammation, and exposure to chemicals like cigarette smoke and teargas. Nociceptors can notify us of danger with fine-tuned precision. Heat nociceptors, for example, send out an alarm only when they’re heated to between 45 and 50 degrees Celsius (about 115 to 125 degrees Fahrenheit), the temperature at which some proteins start to coagulate and cause damage to cells and tissues.

For all that precision, we don’t automatically feel the signals as pain; often the information from nociceptors is parsed by the nervous system along the way. For instance, nociceptors starting in the skin extend through the body to swellings along the spinal cord. They relay their signals to other neurons in those swellings, called dorsal horns, which then deliver signals up to the brain stem. But dorsal horns also contain neurons coming down from the brain that can boost or squelch the signals. As a result, pain in one part of the body can block pain signals from another. If you stick your foot in cold water, touching a hot surface with your hand will hurt less.

What’s the problem to which this is a solution?

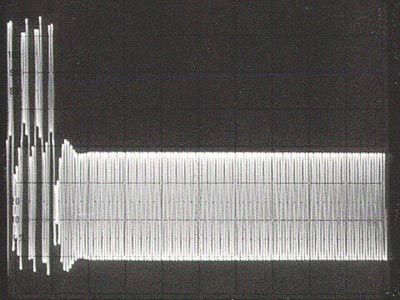

The Rule of 72 deserves to be better known among technical people. It’s a widely-known financial rule of thumb used for understanding and calculating interest rates. But others, including computer scientist and start-up founders, are often concerned with growth rates. Knowing and applying the rule of 72 can help in developing numerical literacy numeracy around growth.

For example, consider Moore’s Law, which describes how “the number of transistors that can be placed inexpensively on an integrated circuit doubles approximately every two years.” If something doubles every two years, at what rate does it increase per month, on average? If you know the rule of 72, you’ll instantly know that the monthly growth rate is about 3%. You get the answer by dividing 72 by 24 (the number of months).

‘Man is a robot with defects.’ –Cioran

Designers and engineers labour to create artificial noises that make life easier whether by generating atmosphere or making you feel more secure. (…)

To produce the ideal clunk, car doors are designed to minimise the amount of high frequencies produced (we associate them with fragility and weakness) and emphasise low, bass-heavy frequencies that suggest solidity. The effect is achieved in a range of different ways – car companies have piled up hundreds of patents on the subject – but usually involves some form of dampener fitted in the door cavity. Locking mechanisms are also tailored to produce the right sort of click and the way seals make contact is precisely controlled. (…)

The EU is still in the process of drafting a law which will require electric vehicle makers to have a signature sound with a minimum volume to make sure other road users can hear the otherwise silent machines whizzing towards them. (…)

While some US sports teams use artificial crowd noise to unsettle the opposition, lots of venues use it as a handy way to help amp up the atmosphere and encourage the real spectators to join in. (…)

Lots of modern telephone systems as well as software like Skype employ noise reduction techniques. Unfortunately, that can result in total silence at quiet points in a conversation and leave you wondering if the call has stopped entirely. To fill those lulls, the software adds artificial noise at a barely audible volume.

When people stop me on the street, they most often say, Stop following me

{ Many species of Pacific predators stick to familiar routes each season, according to new findings of a decade-long study that tracked 23 types of marine animals. The two most heavily trafficked corridors are the California Current along the West Coast of the U.S. and the North Pacific Transition Zone, where cold and warm water meet halfway between Alaska and Hawaii. | Washington Post | full story | photos }

You find yourself trying to do my dance, maybe cause you love me

Each of your senses (sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell) has an individual, specialized hub (cortex) in the brain that collects and filters information from your sensory organs. For example, visual information from your eyes is transmitted directly to the visual cortex,housed in hind portions of the brain. Here, this information is converted into terms (patterns of electrical pulses) that the brain can understand. This filtered visual information is then sent to other regions of the brain, where it is integrated with the other forms of sensory information to create our perception. This process is called ‘multimodal integration’.

Early theories stated that the senses don’t merge until after sensory information is processed. In other words, it was believed that the sensory cortices always operated in isolation. However, about thirty years ago, psychologists began to realize that one sensory system can heavily influence the processing abilities of another. For example, your sight can affect how you brain recognizes sounds.

photo { J. Kursel }

‘It is easy to see the beginnings of things, and harder to see the ends.’ –Joan Didion

Turntable.fm is a little miracle that does something simple and essential: It lets you play your favorite songs for your friends and strangers on the Web, in real time, for free.

I’d say it’s astonishing no one has done it before, but it’s not: The music business has a long tradition of resisting good ideas. So how did the Turntable.fm guys finally get the industry on board?

They haven’t. The start-up doesn’t have deals in place with any labels or publishers.

‘To lead the people, walk behind them.’ –Lao Tzu

I am fascinated with zombies. Always have been, but even more so since I took an interest in microbiology. The zombie apocalypse is the best known and best chronicled viral infection which hasn’t happened. But it could happen any day. (…)

One problem that has to do with zombification is the loss free will. Do zombies have free will? More to the point, do humans have free will?

In two papers entitled A Wasp Manipulates Neuronal Activity in the Sub-Esophageal Ganglion to Decrease the Drive for Walking in Its Cockroach Prey and On predatory wasps and zombie cockroaches — Investigations of “free will” and spontaneous behavior in insects, Ram Gal and Frederic Libersat from Ben Gurion University explore free will in cockroaches. Do cockroaches have free will, or are they just sophisticated automatons? And where do we draw the line between the two?

Gal and Libersat use the following definition for free will: the expression of patterns of “endogenously-generated spontaneous behavior”. That is, a behavior which has a pattern (i.e. not just random fluctuations) and must come from within (i.e. not entirely in response to external stimuli). They cite studies where such behavior — which they define as a “precursor of free will in insects” — is observed. They then show how this behavior is removed from cockroaches when the roaches are attacked by a wasp. (…)

So how about molecular zombies?

The central bank repeated that the recovery is ’somewhat’ slower than initially expected

What Makes a Team Smarter? More Women.

There’s little correlation between a group’s collective intelligence and the IQs of its individual members. But if a group includes more women, its collective intelligence rises. (…)

The standard argument is that diversity is good and you should have both men and women in a group. But so far, the data show, the more women, the better. (…)

Many studies have shown that women tend to score higher on tests of social sensitivity than men do. So what is really important is to have people who are high in social sensitivity, whether they are men or women.

‘No matter how cynical you become, it’s never enough to keep up.’ –Jane Wagner

{ Death penalty costs California $184 million a year, study says. That’s more than $4 billion on capital punishment in California since it was reinstated in 1978, or about $308 million for each of the 13 executions carried out since then. | LA Times }

In our dreams (writes Coleridge) images represent the sensations we think they cause

Tradition relates that, upon waking, he felt that he had received and lost an infinite thing, something he would not be able to recuperate or even glimpse, for the machinery of the world is much too complex for the simplicity of men.

painting { Henry Fuseli, The Shepherds Dream, 1793 }

Best thing for him, really. His therapy was going nowhere.

Are Fast Talkers More Persuasive?

When psychologists first began examining the effect of speech rate on persuasion, they thought the answer was cut-and-dried. In 1976 Norman Miller and colleagues tried to convince participants that caffeine was bad for them (Miller et al., 1976). The results suggested people were most persuaded when the message was delivered at a fully-caffeinated 195 words per minute rather than at a decaffeinated 102 words per minute.

At 195 words per minute, about the fastest that people speak in normal conversation, the message became more credible to those listening, and therefore more persuasive. Talking fast seemed to signal confidence, intelligence, objectivity and superior knowledge. Going at about 100 words per minute, the usual lower limit of normal conversation, was associated with all the reverse attributes. (…)

By the 1980s, though, other researchers had begun to wonder if these results could really be correct. They pointed to studies suggesting that while talking faster seemed to boost credibility, it didn’t always boost persuasion.