Realistically, your chance of winning the jackpot is zero. Technically, it’s one in 175,711,536, or 0.000000569%. Which is statistically the same as zero. But it’s not psychologically the same as zero — and that’s what counts. When you buy your lottery ticket, it’s impossible not to dream of all the things which might happen if you won. (…)

By far the easiest way to funnel more of your income back to the government is to buy lottery tickets. It really is a voluntary tax. (…)

If you move from lottery tickets to scratch cards, something else happens — they pay out with enough predictability that they can actually be used for money laundering. Take your dirty dollars, buy a bunch of scratch cards, redeem the winners, and you’ve got nice clean legitimate money. If the games weren’t so incredibly lucrative for the states, they’d be made illegal in no time just for this reason alone.

{ Reuters | Continue reading }

economics |

March 21st, 2012

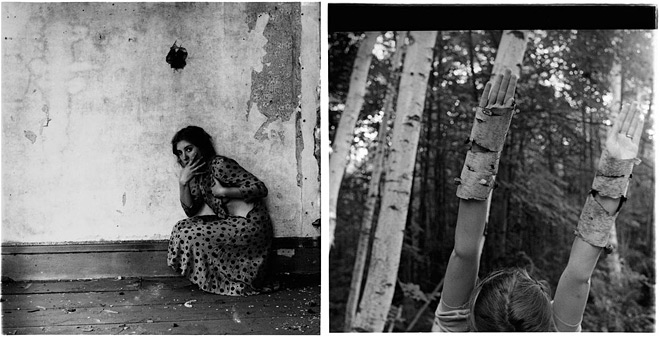

This new research provides a terrific reference list of prior work done on women stalkers and reports a high rate of psychosis among women stalkers. Delusions are the most common symptom in two of the three major studies completed so far. Half of the women stalkers described in prior research had character disorders and women were more likely than men to target a former professional contact (like mental health professionals, teachers or lawyers). It appears that male stalkers are less particular, and more likely to target strangers. Women stalkers seek intimacy.

{ Keen Trial | Continue reading }

photo { Taylor Radelia }

psychology, relationships, weirdos |

March 21st, 2012

photogs |

March 21st, 2012

While sex purges our genome of harmful mutations and pushes biodiversity, it’s a costly exercise for the average organism. (…)

Their new estimates for the origins of reliable eukaryotic fossils now rest at 1.78 to 1.68 billion years ago, and this is where we must currently park the idea of when sex first became popular.

The age-old question that follows is why did sexual reproduction begin? Why didn’t life just keep evolving through cloning and asexual budding systems? (…)

Sex is not an efficient way of sharing genes. When we mate sexually we combine only 50% of our genetic material with our partner’s, whereas asexually budding organisms have 100% of their genetic material carried into the next generation. And Otto highlights what biologists call the ‘cost’ of sex, in that sexually reproducing organisms need to produce twice as many offspring as asexual organisms or they lose out in the population race.

Despite these drawbacks, evolution has shaped the living world in such a way that few large creatures today actually reproduce asexually (only about 0.1% of all living organisms, excluding bacteria). Sex generates variation, and that is certainly a good thing when dealing with constant and unpredictable changes in our environment.

{ Cosmos | Continue reading }

genes, science, sex-oriented |

March 20th, 2012

By all rights, sex shouldn’t exist. Ask most non-biologists what sex is “for,” and they’d probably answer “reproduction,” but they’d be wrong.

In fact, sex is quite simply a terrible way to reproduce.

The reality is that living things can easily make babies without sex, and many do just that. Lots of animals breed asexually, via parthenogenesis (development of an unfertilized egg, without any involvement by males); the list includes many insects, crustaceans, rotifers, flatworms, snails, even some vertebrates including certain species of shark, lizard and the occasional bird. And it’s quite common in plants.

The evolutionary conundrum is that compared to asexual reproduction, breeding sexually poses a daunting number of disadvantages, so many, in fact, that a number of highly regarded evolutionary theorists have concluded rather glumly that sex may actually be a biological liability, something that we—and other species as well—are regrettably stuck with.

{ The Chronicle of Higher Education | Continue reading }

sculpture { Bernini, The Rape of Proserpina, 1621-22 }

science, sex-oriented |

March 20th, 2012

As bacteria evolve to evade antibiotics, common infections could become deadly, according to Dr. Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization.

Speaking at a conference in Copenhagen, Chan said antibiotic resistance could bring about “the end of modern medicine as we know it.”

“We are losing our first-line antimicrobials,” she said Wednesday in her keynote address at the conference on combating antimicrobial resistance. “Replacement treatments are more costly, more toxic, need much longer durations of treatment, and may require treatment in intensive care units.”

Chan said hospitals have become “hotbeds for highly-resistant pathogens” like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, “increasing the risk that hospitalization kills instead of cures.”

Indeed, diseases that were once curable, such as tuberculosis, are becoming harder and more expensive to treat.

{ ABC | Continue reading }

artwork { Mœbius }

health, uh oh |

March 20th, 2012

A team of physicists published a paper drawing on Google’s massive collection of scanned books. They claim to have identified universal laws governing the birth, life course and death of words.

Published in Science, that paper gave the best-yet estimate of the true number of words in English—a million, far more than any dictionary has recorded (the 2002 Webster’s Third New International Dictionary has 348,000). More than half of the language, the authors wrote, is “dark matter” that has evaded standard dictionaries.

The paper also tracked word usage through time (each year, for instance, 1% of the world’s English-speaking population switches from “sneaked” to “snuck”). It also showed that we seem to be putting history behind us more quickly, judging by the speed with which terms fall out of use. References to the year “1880″ dropped by half in the 32 years after that date, while the half-life of “1973″ was a mere decade. (…)

English continues to grow—the 2011 Culturonomics paper suggested a rate of 8,500 new words a year. The new paper, however, says that the growth rate is slowing. Partly because the language is already so rich, the “marginal utility” of new words is declining: Existing things are already well described. This led them to a related finding: The words that manage to be born now become more popular than new words used to get, possibly because they describe something genuinely new (think “iPod,” “Internet,” “Twitter”).

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

image { Larry Welz }

Linguistics |

March 20th, 2012

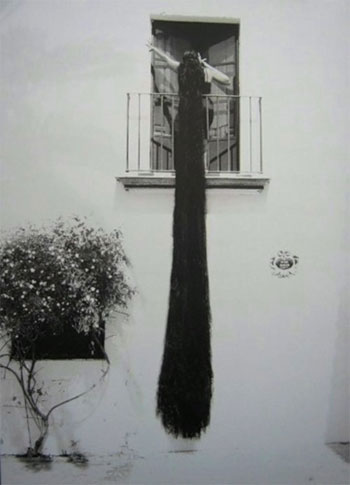

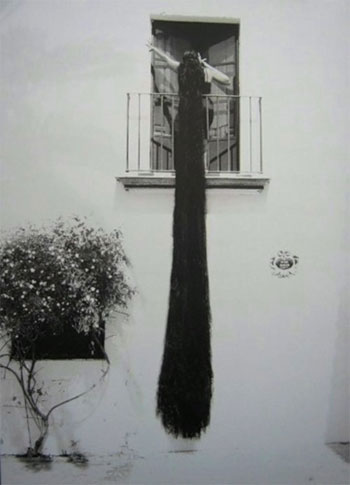

Throughout the centuries hair has been a symbol of status for wealth, class, rank, slavery, royalty, strength, manliness or femininity. And, it still holds a place of value in our postmodern era. Two novels that include hair as a major theme are Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991) and Don Delillo’s Cosmopolis (2003). These two authors create characters heavily involved in the Wall Street world but also swallowed up in their depthless narcissism.

In American Psycho we are introduced to twenty-eight year old Patrick Bateman, a psychopath serial killer who is also a wealthy, narcissistic Wall Street broker. Bateman’s first person narrative is filled with the gruesome crimes he commits, but they are narrated in such a way that it is never clear if he is actually performing the murders. He is obsessed with the material world and confines his life to eating at fancy restaurants, womanizing, purchasing name brand clothes and the most up-to-date electronics, and ensuring the preciseness of his hair.

Twenty-eight year old Eric Packer of Cosmopolis follows many of the traits of his predecessor, but, instead of aimless wandering from fashionable restaurants to name brand designer shops, Packer sets out across New York on a mini-epic journey for a haircut. In his maximum security limousine, Packer views the world from multiple digital screens and purposefully loses his entire financial portfolio in a gamble against the Japanese yen. Within these two novels, hair functions as the external symbol of inward turmoil. Hair becomes a primary symbol through which these two authors create a harsh critique of the modern world of technology, consumerism, and emptiness.

{ Wayne E. Arnold | Continue reading }

books, hair |

March 20th, 2012

Most of us would agree that King Tut and the other mummified ancient Egyptians are dead, and that you and I are alive. Somewhere in between these two states lies the moment of death. But where is that? The old standby — and not such a bad standard — is the stopping of the heart. But the stopping of a heart is anything but irreversible. We’ve seen hearts start up again on their own inside the body, outside the body, even in someone else’s body. Christian Barnard was the first to show us that a heart could stop in one body and be fired up in another. Due to the mountain of evidence to the contrary, it is comical to consider that “brain death” marks the moment of legal death in all fifty states. (…)

Sorensen says that the idea of “irreversibility” makes the determination of death problematic. What was irreversible, say, twenty years ago, may be routinely reversible today. He cites the example of strokes. Brain damage from stroke that was irreversible and led irrevocably to death in the 1940s was reversible in the 1980s. In 1996 the FDA approved tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), a clot-dissolving agent, for use against stroke. This drug has increased the reversibility of a stroke from an hour after symptoms begin to three hours.

In other words, prior to 1996, MRIs of the brains of stroke victims an hour after the onset of symptoms were putative photographs of the moment of death, or at least brain death. Today those images are meaningless.

{ Salon | Continue reading }

health, ideas |

March 20th, 2012

Consider what the modest justices were debating on Monday: what Americans are allowed to do AFTER they die.

Specifically, the question before the court was whether a dead man can help conceive children.

This odd point of law came before the court after a woman, Karen Capato, gave birth to twins 18 months after her husband died of cancer. She had used sperm he deposited when he was alive, and she was seeking his Social Security survivor benefits for the kids. (…)

“Let’s assume Ms. Capato remarried but used her deceased husband’s sperm to birth two children . . . ” Sotomayor posited. “Would they qualify for survivor benefits even though she is now remarried?” (…) “What if you are a sperm donor?”

{ Washington Post | Continue reading }

U.S., kids, law |

March 20th, 2012

Alexander Shulgin, the chemist who re-discovered MDMA (after it was synthesised and abandoned by Merck) and went on to discover hundreds of psychedelic drugs such as the 2C* family. He is famous not only for independently discovering and developing so many psychedelics but for testing them extensively on himself and for writing the core textbooks of the psychedelic literature, PiHKAL (‘Phenethylamines I Have Known and Loved’) and TiHKAL (‘Tryptamines I Have Known and Loved).

{ Neurobonkers | Continue reading }

drugs, flashback |

March 20th, 2012

Researchers at Yale University have developed a new way of seeing inside solid objects, including animal bones and tissues, potentially opening a vast array of dense materials to a new type of detailed internal inspection.

The technique, a novel kind of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), creates three-dimensional images of hard and soft solids based on signals emitted by their phosphorus content.

Traditional MRI produces an image by manipulating an object’s hydrogen atoms with powerful magnets and bursts of radio waves. The atoms absorb, then emit the radio wave energy, revealing their precise location. A computer translates the radio wave signals into images. Standard MRI is a powerful tool for examining water-rich materials, such as anatomical organs, because they contain a lot of hydrogen. But it is hard to use on comparatively water-poor solids, such as bone.

The Yale team’s method targets phosphorus atoms rather than hydrogen atoms, and applies a more complicated sequence of radio wave pulses.

{ Yale News | Continue reading }

artwork { Trevor Brown, Teddy Bear Operation, 2008 }

science, technology |

March 19th, 2012

mathematics, photogs |

March 19th, 2012

A team of researchers that includes a USC scientist has methodically demonstrated that a face’s features or constituents – more than the face per se – are the key to recognizing a person.

Their study, which goes against the common belief that brains process faces “holistically,” appears this month in Psychological Science.

In addition to shedding light on the way the brain functions, these results may help scientists understand rare facial recognition disorders.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Thomas Prior }

faces, neurosciences, photogs |

March 19th, 2012

You’re famous for denying that propositions have to be either true or false (and not both or neither) but before we get to that, can you start by saying how you became a philosopher?

Well, I was trained as a mathematician. I wrote my doctorate on (classical) mathematical logic. So my introduction into philosophy was via logic and the philosophy of mathematics. But I suppose that I’ve always had an interest in philosophical matters. I was brought up as a Christian (not that I am one now). And even before I went to university I was interested in the philosophy of religion – though I had no idea that that was what it was called. Anyway, by the time I had finished my doctorate, I knew that philosophy was more fun than mathematics, and I was very fortunate to get a job in a philosophy department (at the University of St Andrews), teaching – of all things – the philosophy of science. In those days, I knew virtually nothing about philosophy and its history. So I have spent most of my academic life educating myself – usually by teaching things I knew nothing about; it’s a good way to learn! Knowing very little about the subject has, I think, been an advantage, though. I have been able to explore without many preconceptions. And I have felt free to engage with anything in philosophy that struck me as interesting.

{ Graham Priest interviewed by Richard Marshal | Continue reading }

photo { Robert Whitman }

ideas |

March 19th, 2012

Several theories claim that dreaming is a random by-product of REM sleep physiology and that it does not serve any natural function.

Phenomenal dream content, however, is not as disorganized as such views imply. The form and content of dreams is not random but organized and selective: during dreaming, the brain constructs a complex model of the world in which certain types of elements, when compared to waking life, are underrepresented whereas others are over represented. Furthermore, dream content is consistently and powerfully modulated by certain types of waking experiences.

On the basis of this evidence, I put forward the hypothesis that the biological function of dreaming is to simulate threatening events, and to rehearse threat perception and threat avoidance.

To evaluate this hypothesis, we need to consider the original evolutionary context of dreaming and the possible traces it has left in the dream content of the present human population. In the ancestral environment, human life was short and full of threats. Any behavioral advantage in dealing with highly dangerous events would have increased the probability of reproductive success. A dream-production mechanism that tends to select threatening waking events and simulate them over and over again in various combinations would have been valuable for the development and maintenance of threat-avoidance skills.

Empirical evidence from normative dream content, children’s dreams, recurrent dreams, nightmares, post traumatic dreams, and the dreams of hunter-gatherers indicates that our dream-production mechanisms are in fact specialized in the simulation of threatening events, and thus provides support to the threat simulation hypothesis of the

{ Antti Revonsuo/Behavioral and Bain Sciences | PDF }

archives, psychology, science, theory |

March 19th, 2012

architecture, flashback |

March 19th, 2012

According to a paper just published (but available online since 2010), we haven’t found any genes for personality.

The study was a big meta-analysis of a total of 20,000 people of European descent. In a nutshell, they found no single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with any of the “Big 5″ personality traits of Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness. There were a couple of very tenuous hits, but they didn’t replicate.

Obviously, this is bad news for people interested in the genetics of personality.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

image { Pole Edouard }

genes, psychology |

March 19th, 2012

We have all had arguments. Occasionally these reach an agreed upon conclusion but usually the parties involved either agree to disagree or end up thinking the other party hopelessly stupid, ignorant or irrationally stubborn. Very rarely do people consider the possibility that it is they who are ignorant, stupid, irrational or stubborn even when they have good reason to believe that the other party is at least as intelligent or educated as themselves.

Sometimes the argument was about something factual where the facts could be easily checked e.g. who won a certain football match in 1966.

Sometimes the facts aren’t so easily checked because they are difficult to understand but the problem is clear and objective. (…)

Sometimes the facts aren’t as mathematical or logical as the Monty Hall solution. Each party to the argument appeals to ‘facts’ which the other party disputes. (…)

Sometimes the arguments boil down to differences in values. For example, what tastes better chocolate or vanilla ice cream, or who is prettier Jane or Mary? In these cases there isn’t really a correct answer – even when a large majority favors a particular alternative. Values also have a strong way of influencing what people accept as evidence or indeed what they perceive at all.

The interesting thing is that when the disagreement isn’t a pure values difference it should always be possible to reach agreement.

{ Garth Zietsman | Continue reading }

controversy, ideas, relationships |

March 19th, 2012

New support for the value of fiction is arriving from an unexpected quarter: neuroscience.

Brain scans are revealing what happens in our heads when we read a detailed description, an evocative metaphor or an emotional exchange between characters. Stories, this research is showing, stimulate the brain and even change how we act in life.

Researchers have long known that the “classical” language regions, like Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area, are involved in how the brain interprets written words. What scientists have come to realize in the last few years is that narratives activate many other parts of our brains as well, suggesting why the experience of reading can feel so alive. Words like “lavender,” “cinnamon” and “soap,” for example, elicit a response not only from the language-processing areas of our brains, but also those devoted to dealing with smells. (…)

Researchers have discovered that words describing motion also stimulate regions of the brain distinct from language-processing areas. (…)

The brain, it seems, does not make much of a distinction between reading about an experience and encountering it in real life; in each case, the same neurological regions are stimulated. (…) Fiction — with its redolent details, imaginative metaphors and attentive descriptions of people and their actions — offers an especially rich replica. Indeed, in one respect novels go beyond simulating reality to give readers an experience unavailable off the page: the opportunity to enter fully into other people’s thoughts and feelings. (…) Scientists call this capacity of the brain to construct a map of other people’s intentions “theory of mind.” Narratives offer a unique opportunity to engage this capacity, as we identify with characters’ longings and frustrations, guess at their hidden motives and track their encounters with friends and enemies, neighbors and lovers. (…)

Reading great literature, it has long been averred, enlarges and improves us as human beings. Brain science shows this claim is truer than we imagined.

{ NYT | Continue reading }

books, neurosciences, psychology |

March 19th, 2012