books

A high-ranking FBI agent filed a sensitive internal manual detailing the bureau’s secret interrogation procedures with the Library of Congress, where anyone with a library card can read it. […]

“A document that has not been released does not even need a copyright,” says Steven Aftergood, a government secrecy expert at the Federation of American Scientists. “Who is going to plagiarize from it? Even if you wanted to, you couldn’t violate the copyright because you don’t have the document. It isn’t available.”

{ Mother Jones | Continue reading }

U.S., books, law | December 23rd, 2013 5:50 am

Features of fictional folk are more extreme than in reality; real folks are boring by comparison. Fictional folks are more expressive, and give off clearer signs about their feelings and intentions. Their motives are simpler and clearer, and their actions are better explained by their motives and local visible context. Who they are now is better predicted by their history. […]

In real life, coincidence happens all the time. But in fiction […] Your readers will refuse to believe it.

{ via overcoming bias | Continue reading }

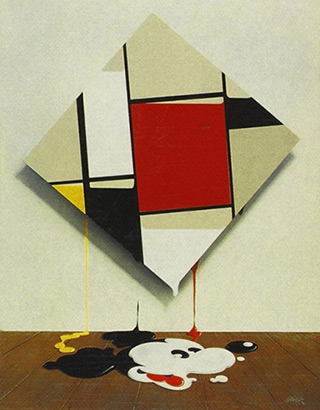

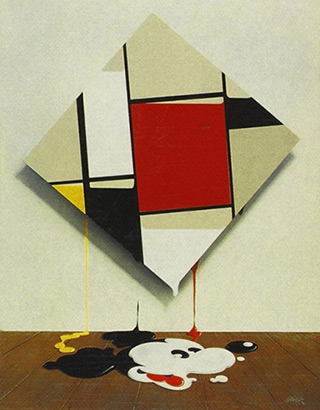

photo { Mick Haggerty, Mickey Mondrian, 1976 }

books | December 13th, 2013 3:02 pm

As you mature you find that because your personality is already created, you’re kind of using other characters to understand yourself. The process of maturation makes you naturally more inclined to relate to problematic people. […]

“Hate” and “Love” aren’t opposites. The opposite of “Love” is “Indifferent.” So if you actually hate something, it actually means you have a pretty deep emotional investment with what that expression means.

{ Interview with Chuck Klosterman | Continue reading }

“The drug lords on ‘The Wire’ were criminals, but they had a stricter ethical code than the corrupt police trying to stop them,” Mr. Klosterman wrote in his analysis of the HBO show and its complex characters.

“The most admirable adult in the series was Omar Little, a hyperviolent stickup artist who lived by a street code so austere he wouldn’t even cuss (in 2012, Barack Obama cited Omar as his favorite ‘Wire’ character, thus making Obama the first sitting president to express admiration for a fictional homosexual who killed dozens of people with a shotgun).”

{ Pittsburgh News | Continue reading }

photo { Olivia Locher }

books, ideas | October 23rd, 2013 12:01 pm

Within a week of Random House and Penguin merging to become the world’s largest books publisher with an estimated revenue of $4 billion, the aftershocks have started. The new entity, eager to cut cost and streamline operations, has asked author Vikram Seth to return his $1.7 million advance, a part of which was paid to him for A Suitable Girl, the ‘jumpsequel’ to his best-selling novel, A Suitable Boy.

Seth, one of the world’s bestloved writers, was scheduled to submit his manuscript this June but has been unable to do so, leading to the publishers’ demarche. […]

“It’s possible that Vikram Seth has not started on the book or that it’s nowhere close to completion, which explains the move.”

{ Mumbai Mirror | Continue reading }

books, economics | July 9th, 2013 3:40 pm

Last August, a book titled “Leapfrogging” hit The Wall Street Journal’s list of best-selling business titles upon its debut. The following week, sales of the book, written by first-time author Soren Kaplan, plunged 99% and it fell off the list.

Something similar happened when the hardcover edition of “Networking is Dead,” was published in mid-December. A week after selling enough copies to make it onto the Journal’s business best-seller list, more hardcover copies of the book were returned than sold, says book-sales tracker Nielsen BookScan.

It isn’t uncommon for a business book to land on best-seller lists only to quickly drop off. But even a brief appearance adds permanent luster to an author’s reputation, greasing the skids for speaking and consulting engagements.

Mr. Kaplan says the best-seller status of “Leapfrogging” has “become part of my position as a speaker and consultant.”

But the short moment of glory doesn’t always occur by luck alone. In the cases mentioned above, the authors hired a marketing firm that purchased books ahead of publication date, creating a spike in sales that landed titles on the lists. The marketing firm, San Diego-based ResultSource, charges thousands of dollars for its services in addition to the cost of the books, according to authors interviewed.

{ WSJ | Continue reading | via Forbes }

installation { Tom Sachs }

books, economics, scams and heists | February 25th, 2013 7:07 am

In school they tell you time is an illusion, but the profs over-complicate it if you ask me. There’s no such thing as before and after, just a big mash of now. “Time” is something our brains make up to help us get from point A to point B. Like the long path up to Stacy Adams’ house. Someone put it there so you wouldn’t walk around the woods in circles, not getting anywhere. Soon as scientists figured that out, they knew you could make time your bitch. You can stretch it and squash it and reshape it. You just need the right drugs and hardware.

Someday we’ll tell our kids about the night we saw our first Quantum Condenser, that’s what my Lou says on the path up to Stacy Adams’ house. Lou’s into the steevy new gear. I tend to wait for the third or fourth gen when shit actually gets good. But I have to admit I’m excited to see a real life QC. Stacy’s family was the first in the boro to get one. Her dad works at Bubble Labs, where they invented the thing.

You think she’ll let us use it? Lou asks.

I shrug. Then I tickle him because he’s obviously so excited. He shoves me away and then pulls me in and we go arms-around-waists, bumping against each other up the path. Me and my Lou.

Up the hill we go Hi Ho, up to Stacy’s big glass house at the top of the town like Mount Olympus (we just did that mod in Ancient History), and when we ring the bell Stacy’s there in her green double-breasted party suit.

Boys, she goes. Party’s in the back. Come on in.

{ John M. Cusick | Continue reading }

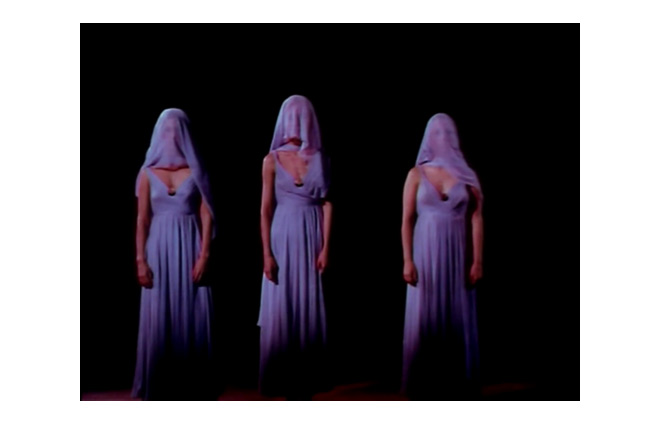

photos { Lorenzo Sala | Inez Van Lamsweerde & Vinoodh Matadin }

books, time | February 12th, 2013 2:07 pm

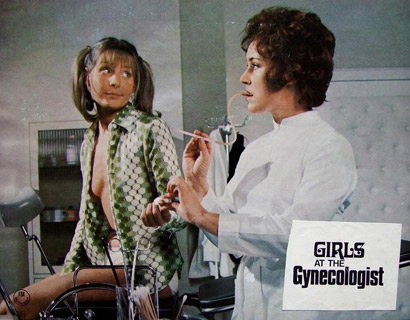

Darwinian literary analysis is a way to examine texts and arrive at conclusions about evolved human behaviors, motivations, and emotions. That is, by analyzing texts, it is possible to indirectly analyze human nature. Recently, scholars have examined the works of Jane Austen, Harlequin romance novels, and folktales for this purpose. Although this prior work has been informative, it has only included heterosexual relationships.

Symons noted that lesbian and gay populations are a vital group to gain insight into evolutionary sex differences, as their relationships involve only same sex individuals, thus highlighting dominant female and male mating behaviors. Therefore, in this paper, our primary goal is to analyze lesbian pulp fiction to better comprehend women’s evolved mating strategies. We also consider the era that these books were most popular and explore the cultural climate in relation to the characters in the novels. In general, the way the characters are described and their relationship dynamics are consistent gender stereotypes concerning masculine versus feminine women.

{ Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology | PDF }

books, relationships, science | January 22nd, 2013 7:27 am

Reviews on Amazon are becoming attack weapons, intended to sink new books as soon as they are published.

In the biggest, most overt and most successful of these campaigns, a group of Michael Jackson fans used Facebook and Twitter to solicit negative reviews of a new biography of the singer. They bombarded Amazon with dozens of one-star takedowns, succeeded in getting several favorable notices erased and even took credit for Amazon’s briefly removing the book from sale.

“Books used to die by being ignored, but now they can be killed — and perhaps unjustly killed,” said Trevor Pinch, a Cornell sociologist who has studied Amazon reviews. “In theory, a very good book could be killed by a group of people for malicious reasons.”

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

books, economics, social networks | January 21st, 2013 9:57 am

books, drugs, haha | January 20th, 2013 3:09 pm

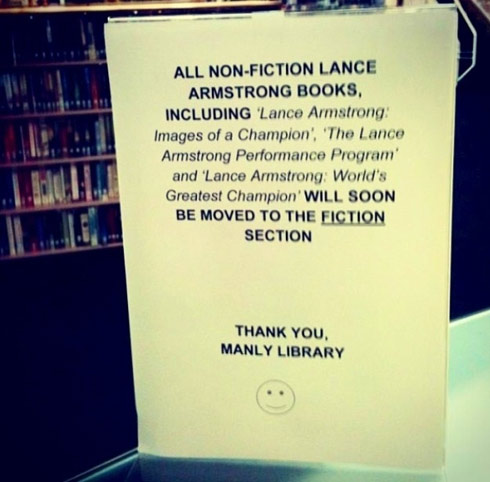

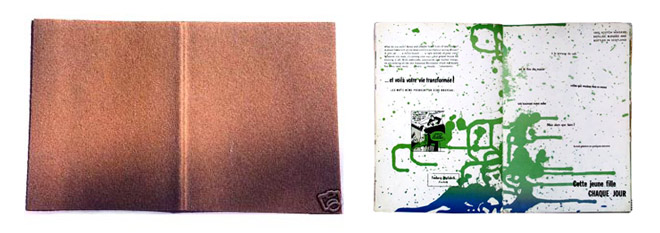

Guy Debord’s first book, Mémoires, was bound with a sandpaper cover so that it would destroy other books placed next to it.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Mémoires was written, or rather assembled, by Guy Debord and Asger Jorn in 1957. Debord himself often referred to Mémoires as an anti-book. […] The text is entirely composed of fragments taken from other texts: photographs, advertisements, comic strips, poetry, novels, philosophy, pornography, architectural diagrams, newspapers, military histories, wood block engravings, travel books, etc. Each page presents a collage of such materials connected or effaced by Jorn’s structures portantes, lines or amorphous painted shapes that mediate the relationships between the fragments.

{ via David Banash | Continue reading }

books, visual design | January 10th, 2013 2:36 pm

When we read a text, we hear a voice talking to us. Yet the voice changes over time. In his new book titled Poesins röster, Mats Malm, professor in comparative literature at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, shows that when reading older literature, we may hear completely different voices than contemporary readers did – or not hear any voices at all.

‘When we read a novel written today, we hear a voice that speaks pretty much the same language we speak, and that addresses people and things in a way we are used to. But much happens as a text ages – a certain type of alienation emerges. The reader may still hear a voice, but will not understand it fully and therefore risks missing important aspects,’ says Mats Malm.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

books, psychology | October 15th, 2012 10:19 am

books, visual design | October 3rd, 2012 4:31 pm

Back in 2009, The Millions started its “Difficult Books” series–devoted to identifying the hardest and most frustrating books ever written, as well as what made them so hard and frustrating. The two curators, Emily Colette Wilkinson and Garth Risk Hallberg, have selected the most difficult of the most difficult. […]

To The Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf - In its intermingling of separate consciousnesses, Virginia Woolf’s fiction is both intellectually and psychically difficult. Not only is it hard to tell who’s who and who’s saying or thinking what, it is also disconcerting—even queasy-making—to be set adrift in other minds, with their private rhythms and associative patterns. It feels, at times, like being occupied by an alien consciousness. […]

Women & Men by Joseph McElroy - In this space I could put any number of postmodern meganovels - a subgenre I’ve been smitten with for many years now. There’s William Gaddis’ JR, which is easier than people make it out to be, and Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, which is harder. There’s The Recognitions and Mason & Dixon. There’s William H. Gass’ The Tunnel - verbally lucid, but morally arduous. Of the lot, though, I’d like to shine the spotlight again on Joseph McElroy’s Women & Men. It is longer than any of the foregoing, and, in the idiosyncracies of its prose, on par with the hardest. Parts of it, anyway. Its temperament, though, is completely sui generis - warm, humanist, synthetic rather than analytic.

{ Publishers Weekly | Continue reading }

books | August 17th, 2012 4:22 pm

Small children (age 4-6) who were exposed to a large number of children’s books and films had a significantly stronger ability to read the mental and emotional states of other people. … The more absorbed subjects were in the story, the more empathy they felt, and the more empathy they felt, the more likely the subjects were to help when the experimenter “accidentally” dropped a handful of pens… Reading narrative fiction … fosters empathic growth and prosocial behavior. […]

Psychologists have found that people who watch less TV are actually more accurate judges of life’s risks and rewards than those who subject themselves to the tales of crime, tragedy, and death that appear night after night on the ten o’clock news. That’s because these people are less likely to see sensationalized or one-sided sources of information, and thus see reality more clearly.

{ OvercomingBias | Continue reading }

image { Gary Stephen Brotmeyer }

books, ideas, media, psychology | May 11th, 2012 12:06 pm

When you “lose yourself” inside the world of a fictional character while reading a story, you may actually end up changing your own behavior and thoughts to match that of the character, a new study suggests.

Researchers at Ohio State University examined what happened to people who, while reading a fictional story, found themselves feeling the emotions, thoughts, beliefs and internal responses of one of the characters as if they were their own - a phenomenon the researchers call “experience-taking.”

They found that, in the right situations, experience-taking may lead to real changes, if only temporary, in the lives of readers.

{ Ohio State University | Continue reading }

photo { Joel Sternfeld }

books, psychology | May 7th, 2012 1:44 pm

Historically, the book, almost alone, has resisted that great colonizing form of our age, the ad. That, in turn, meant you could be assured of one thing when you opened its covers: that you were alone in the book’s world and time. No longer. Sooner or later, the one thing the coming successor generations of e-book are guaranteed to do is smash the traditional reading experience, that sense — when you step inside those covers — of having plunged into another universe. You can’t really remain in another universe long with your email pinging in the background. So the book, enveloped in our busy world and the barrage of images, information, and so much else that comes our way incessantly, is bound to morph into something different, as is the experience of reading it.

{ Tom Dispatch | Continue reading }

artwork { Chad Person }

books, economics, ideas, technology | April 23rd, 2012 6:31 am

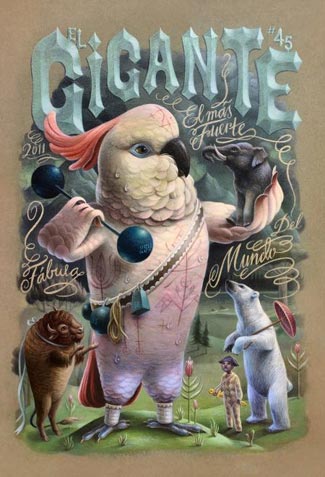

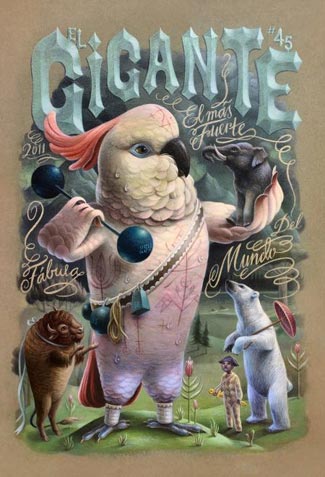

{ 1.Francesco Ercolini | 2. Calla }

quote { Pierre Louÿs, Manuel de civilité pour les petites filles à l’usage des maisons d’éducation, 1926-1927 | full text | Wikipedia }

books, horse, sex-oriented | April 20th, 2012 11:42 am

In my new book Drop Dead Healthy, I try to become the healthiest person alive. In doing so, I examine hundreds of activities to determine if they are healthy.

Is meditation healthy? Yes. Petting dogs? Yes, because it lowers the blood pressure. Sitting? Definitely not. Going to a noisy restaurant? No. Taking naps? Thank God yes.

One of the few activities I didn’t discuss: Reading. Is reading healthy? Or will it slowly murder you?

No doubt I’m a bit biased, but I’ve come to the conclusion that overall, books are, in fact, good for your health. (…)

More and more research shows that sitting is bad for you. It significantly increases your chances of heart disease and slows your metabolism.

This is why, for my book, I ignored the siren call of my chair and did a lot of reading standing up. Reading on your feet burns about 34 more calories per hour than reading while sitting. Eventually, I took it further. I bought a treadmill, converted it into a desk, and did all my reading and writing while walking. It took me about a thousand miles to write the book.

{ AJ Jacobs/Omnivoracious | Continue reading }

books, guide, health | April 13th, 2012 6:45 am

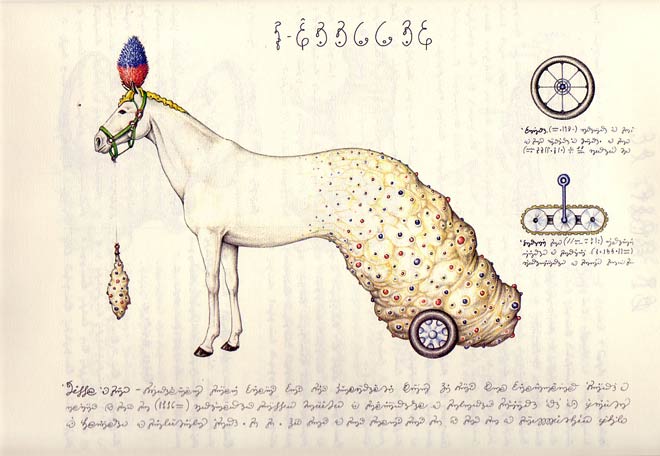

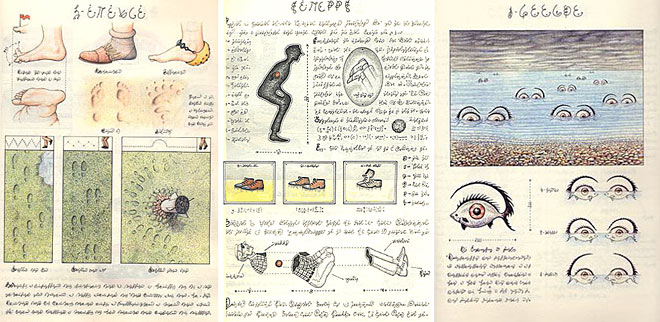

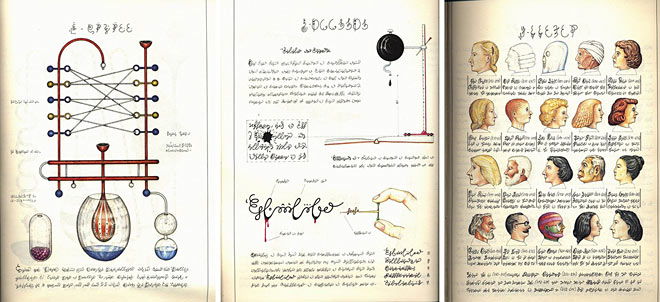

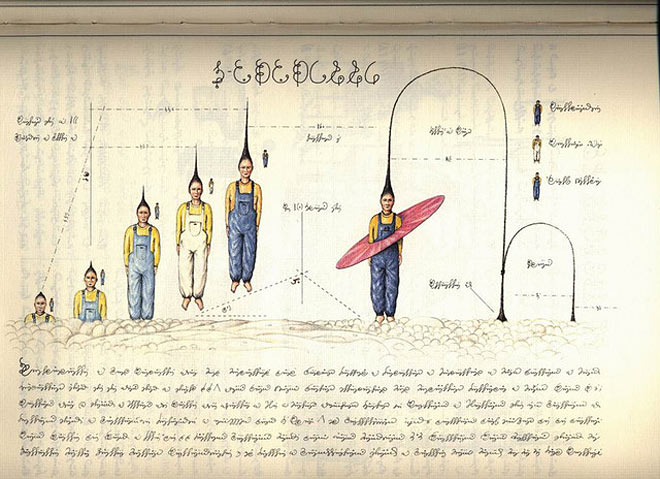

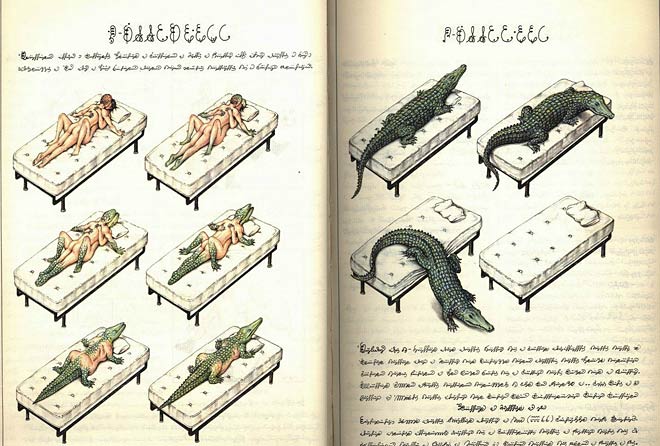

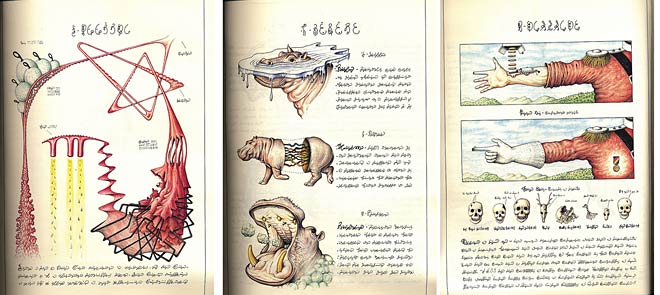

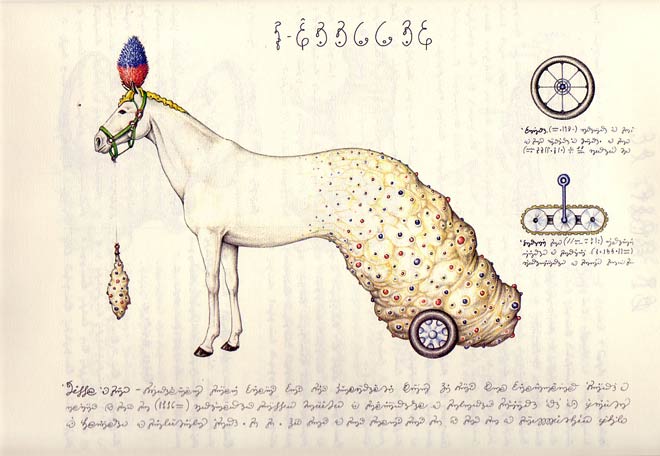

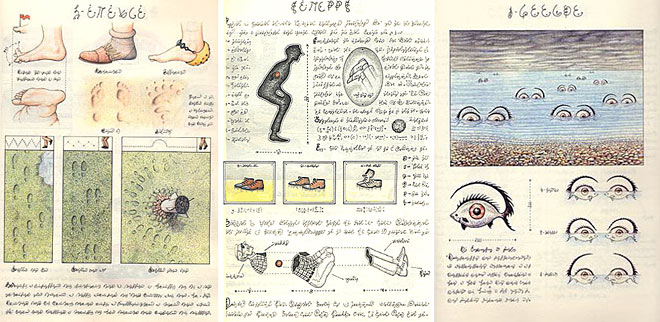

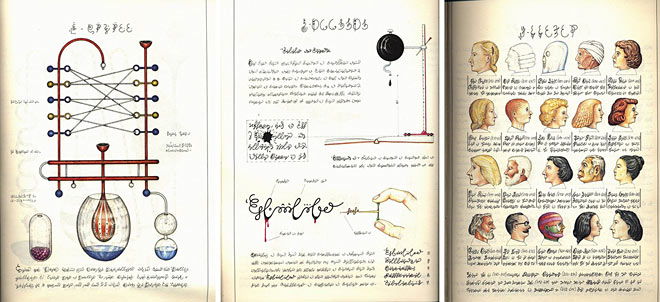

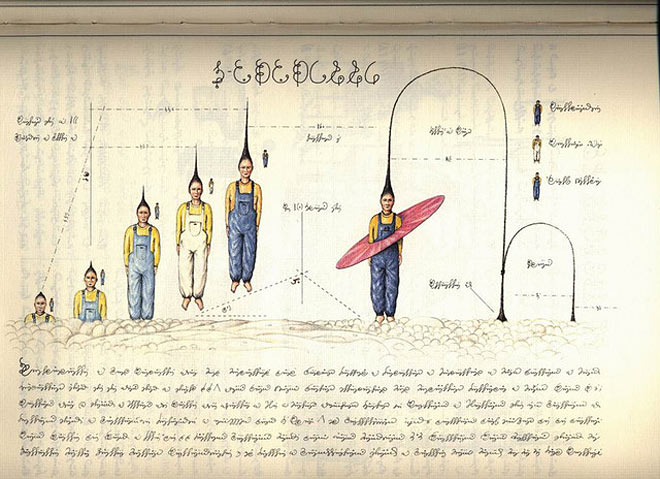

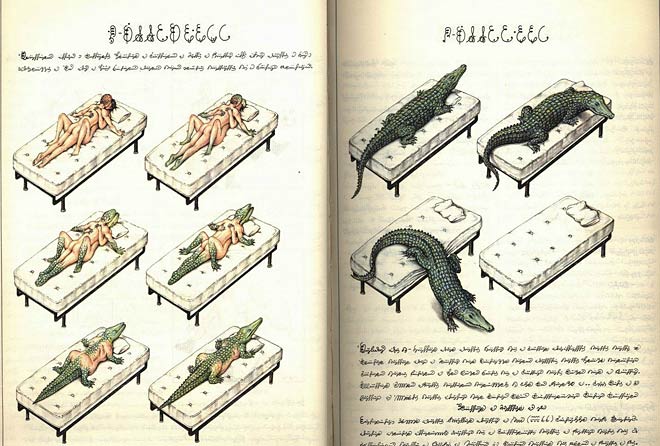

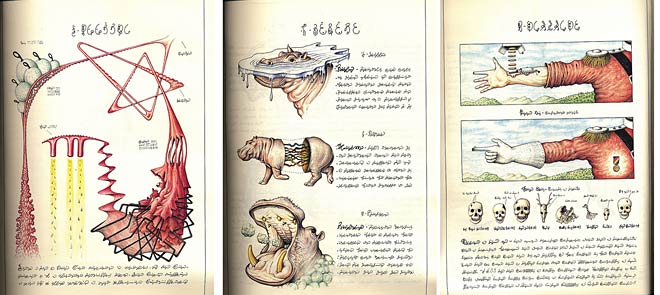

Codex Seraphinianus, originally published in 1981, is an illustrated encyclopedia of an imaginary world, created by the Italian artist, architect and industrial designer Luigi Serafini during thirty months, from 1976 to 1978. The book is approximately 360 pages long (depending on edition), and written in a strange, generally unintelligible alphabet. (…)

The book is an encyclopedia in manuscript with copious hand-drawn colored-pencil illustrations of bizarre and fantastical flora, fauna, anatomies, fashions, and foods. It has been compared to the Voynich manuscript,[3] “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”, and the works of M.C. Escher[6] and Hieronymus Bosch. (…)

In a talk at the Oxford University Society of Bibliophiles held on 12 May 2009, Serafini stated that there is no meaning hidden behind the script of the Codex, which is asemic; that his own experience in writing it was closely similar to automatic writing; and that what he wanted his alphabet to convey to the reader is the sensation that children feel in front of books they cannot yet understand, although they see that their writing does make sense for grown-ups.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading | Thanks to Adam John Williams }

books, visual design | March 23rd, 2012 10:05 am

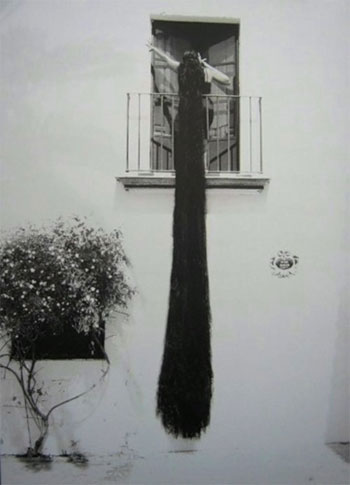

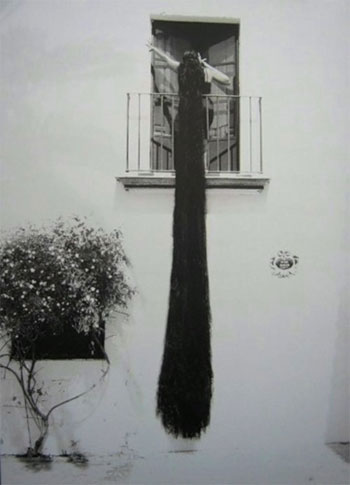

Throughout the centuries hair has been a symbol of status for wealth, class, rank, slavery, royalty, strength, manliness or femininity. And, it still holds a place of value in our postmodern era. Two novels that include hair as a major theme are Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991) and Don Delillo’s Cosmopolis (2003). These two authors create characters heavily involved in the Wall Street world but also swallowed up in their depthless narcissism.

In American Psycho we are introduced to twenty-eight year old Patrick Bateman, a psychopath serial killer who is also a wealthy, narcissistic Wall Street broker. Bateman’s first person narrative is filled with the gruesome crimes he commits, but they are narrated in such a way that it is never clear if he is actually performing the murders. He is obsessed with the material world and confines his life to eating at fancy restaurants, womanizing, purchasing name brand clothes and the most up-to-date electronics, and ensuring the preciseness of his hair.

Twenty-eight year old Eric Packer of Cosmopolis follows many of the traits of his predecessor, but, instead of aimless wandering from fashionable restaurants to name brand designer shops, Packer sets out across New York on a mini-epic journey for a haircut. In his maximum security limousine, Packer views the world from multiple digital screens and purposefully loses his entire financial portfolio in a gamble against the Japanese yen. Within these two novels, hair functions as the external symbol of inward turmoil. Hair becomes a primary symbol through which these two authors create a harsh critique of the modern world of technology, consumerism, and emptiness.

{ Wayne E. Arnold | Continue reading }

books, hair | March 20th, 2012 12:20 pm