economics

Disaster and rebirth is an old story in this part of the country. I know. My family has lived that cycle for generations deep in the Mississippi Delta—in Plaquemines Parish, a name that since the British Petroleum (BP) oil spill has become a cultural marker, the equal, after Katrina, of “the Lower Ninth Ward.” But the oil spill? Will it prove one too many disasters for the return of the Plaquemines Parish my family once knew? Or will it, like Hurricane Katrina, be a dangerous opportunity for changes long overdue?

As much of America suddenly knows, the mouth of the Mississippi River and the surrounding marshlands of Plaquemines Parish nurture the foodstuffs that grace the tables of New Orleans’s world-famous restaurants and provide much of the seafood—25 to 30 percent of it—that Americans eat. Over two centuries the region’s diverse, amphibious Delta culture—Alsatian, Croatian, Isleño, African American, Italian, and Native American—also nurtured my family’s culinary roots that flowered into the Ruth’s Chris Steak House restaurant empire.

{ Randy Fertel/Gastronomica | Continue reading }

photo { Jessica Craig-Martin }

U.S., economics, food, drinks, restaurants, oil | March 18th, 2011 10:35 am

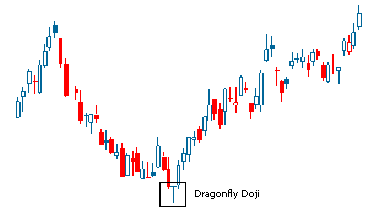

A dragonfly doji pattern is a relatively difficult chart pattern to find, but when it is found within a defined trend it is often deemed to be a reliable signal indecision among traders and that the trend is about to change direction.

The pattern is formed when the stock’s opening and closing prices are equal and occur at the high of the day. The long lower shadow suggests that the forces of supply and demand are nearing a balance and that the direction of the trend may be nearing a major turning point.

{ Investopedia | Continue reading }

allegories, traders | March 16th, 2011 10:18 am

Preventing preterm births just got 150 times more expensive, now that KV Pharmaceuticals has gained exclusive rights to produce a progesterone shot used to prevent premature births in high-risk mothers.

Although the shot has been available in unregulated form from specialty compounding pharmacies for years for $10 a pop, the Food and Drug Administration recently granted KV Pharmaceuticals sole rights to produce the drug, which will be marketed as Makena and cost $1,500 per dose — an estimated $30,000 in total per pregnancy. (…)

Because FDA laws prohibit compounding pharmacies from making FDA-approved products, doctors will be legally obligated to stop using the cheaper version of this drug.

{ ABC News | Continue reading }

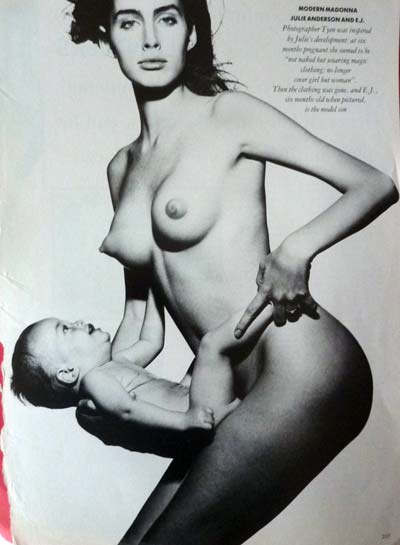

photo { Julie Anderson and E.J. photographed by Tyen }

buffoons, economics, health | March 14th, 2011 6:05 pm

{ Edward Weston, White Sands, 1946 }

related { The Cloud: Battle of the Tech Titans. Amazon, Google, and Microsoft are going up against traditional infrastructure makers like IBM and HP as businesses move their most important work to cloud computing, profoundly changing how companies buy computer technology. | Business week | full story }

economics, google, photogs, technology | March 14th, 2011 5:10 pm

John Gapper makes a good point: management consultants in general, and McKinsey consultants in particular, have made their entire business out of exploiting the moral grey zone surrounding confidential information.

The reason you hire McKinsey is that its consultants have seen strategic business issues like yours before, and therefore might have developed good insights into how to approach them. But the reason they’re familiar with those issues is that they’ve been given highly confidential information about your competitors. So when you hire McKinsey you’re essentially trying to acquire, for a very high hourly fee, the kind of corporate intelligence that can only be built up through long exposure to highly-sensitive commercial information. (…)

In this sense, a management consultant is a bit like an art dealer, or anybody else who traffics in valuable information asymmetries. The consultant knows more than the client, when it comes to strategic issues within the industry in question. If the client wants access to that knowledge, he has to open his own kimono to get it, thereby putting the consultant at yet more of an information advantage.

{ Felix Salmon/Reuters | Continue reading }

economics, ideas | March 11th, 2011 5:20 pm

It should be so easy: Buy toothpaste. But few shopping trips are more bewildering.

An explosion of specialized pastes and gels brag about their powers to whiten teeth, reduce plaque, curb sensitivity and fight gingivitis, sometimes all at the same time. Add in all the flavors and sizes, plus ever-rising prices, and the simple errand turns into sensory overload.

Manufacturers acknowledge the problem and are putting the brakes on new-product introductions. Last year, 69 new toothpastes hit store shelves, down from 102 in 2007. (…)

Stores are trying to simplify, too. Last month, 352 distinct types or sizes of toothpaste were sold at retail, down from 412 in March 2008. (…)

With some 93% of U.S. adults using toothpaste, according to Mintel, there’s little room to recruit new users.

Even through the recession, when unit sales of toothpaste actually dipped, prices kept rising. The average price of toothpaste last year reached $2.83, up 8% over the past four years.

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

economics, teeth | March 7th, 2011 6:27 pm

What happens after Yahoo acquires you.

Whether it’s Flickr, Delicious, MyBlogLog, or Upcoming, the post-purchase story is a similar one. Both sides talk about all the wonderful things they will do together. Then reality sets in. They get bogged down trying to overcome integration obstacles, endless meetings, and stifling bureaucracy. The products slow down or stop moving forward entirely. Once they hit the two-year mark and are free to leave, the founders take off.

{ 37signals | Continue reading }

economics, technology | February 28th, 2011 6:00 pm

In October 2009 John Walkenbach noticed that the price of the Kindle was falling at a consistent rate, lowering almost on a schedule. By June 2010, the rate was so unwavering that he could easily forecast the date at which the Kindle would be free: November 2011.

In August, 2010 I had the chance to point it out to Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon. He merely smiled and said, “Oh, you noticed that!” And then smiled again. When I brought it to the attention of publishing veterans they would often laugh nervously. How outrageous! they would say. It must cost something to make? The trick was figuring out how Amazon could bundle the free Kindle and still make money. My thought was the cell phone model: a free Kindle if you buy X number of e-books.

But last week Michael Arrington at TechCruch reported on a rumor which hints at a more clever plan: a free Kindle for every Prime customer of Amazon. Prime customers pay $79 per year for free 2-day shipping, and as of last week, free unlimited streaming movies (a la Netflix). Arrington writes:

In January Amazon offered select customers a free Kindle of sorts – they had to pay for it, but if they didn’t like it they could get a full refund and keep the device. It turns out that was just a test run for a much more ambitious program. A reliable source tells us Amazon wants to give a free Kindle to every Amazon Prime subscriber.

{ The Technium | Continue reading }

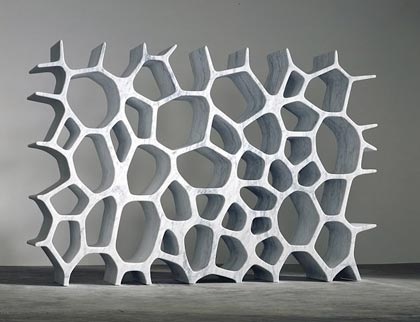

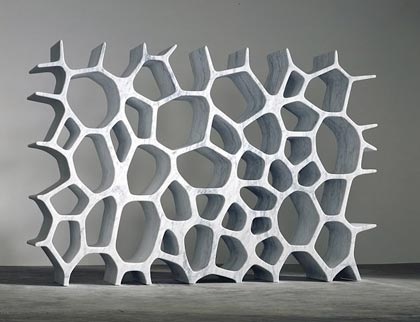

artwork { Marc Newson, Voronoi Shelf, 2006 | white Carrara marble }

related { Netflix Adds Subtitles to More Streaming Content, Stirs Up Controversy. }

economics, technology | February 28th, 2011 5:50 pm

{ Breast Milk Ice Cream A Hit At London Store | NPR | full story }

economics, food, drinks, restaurants | February 28th, 2011 5:20 pm

What gold does have is some rather remarkable physical properties that make it very likely that people will continue to value it highly: luster, corrosion resistance, divisibility, malleability, high thermal and electrical conductivity, and a high degree of scarcity. All the gold ever mined would only fill one large swimming pool, and most of that gold is still recoverable. (…)

The gold that was once locked up at Fort Knox is gone. It has been 40 years since the last indirect link between the dollar and gold was severed, and yet the government continues to hold some 8,000 metric tons of gold bullion—the world’s largest single stash. Oddly enough it is valued at $42 per ounce, the last official price before it was set free to be established in free trading. At today’s market price of around $1,300 per ounce, the hoard would be valued in the hundreds of billions of dollars, although that much gold could not be dumped precipitously without suppressing the price. (…)

But is the gold still there? Yes, almost certainly, though we hear occasional calls for an outside audit. A more plausible accusation is that some of it has been leased to short sellers. This is a common practice among central banks that offers distinct benefits to the government. First, it earns a bit of interest income. More important, it can covertly suppress the gold price. Rising gold prices annoy Treasury secretaries and central bankers because the rise implies falling confidence in their currency. Leased gold remains in the vault and on the balance sheet even though it (or rather a paper claim on it) has been sold to someone else. Although one can find rumors on the Internet, there is no way, short of a thorough audit, to know the extent of gold leasing by the U.S. government, if any.

{ Freeman | Continue reading }

economics | February 28th, 2011 12:37 pm

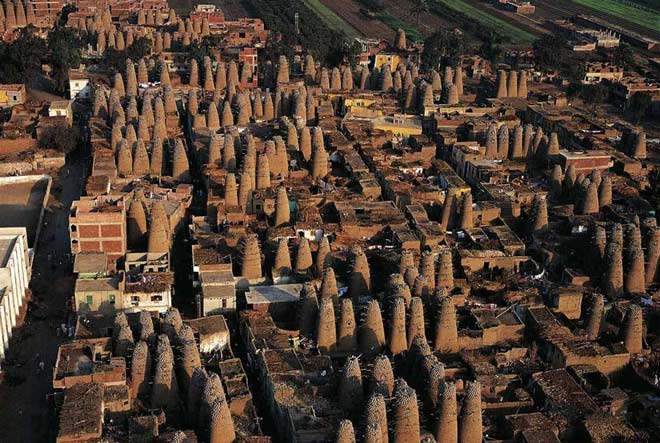

The 27-page shareholder letter Berkshire Hathaway chief executive Warren Buffett just released reads like a motivational speech or a pep talk trying to win over an audience that is increasingly pessimistic about America’s future: “In 2011, we will set a new record for capital spending – $8 billion – and spend all of the $2 billion increase in the United States,” he writes. “Now, as in 1776, 1861, 1932 and 1941, America’s best days lie ahead.”

(Of course, Buffett also disclosed that Berkshire failed to outperform the S&P 500 in 2010 for the second year running, the first time in the company’s history that has happened.)

In any case, the letter is also replete with anecdotes that illuminate activity across various sectors of the U.S. economy. The style is somewhat reminiscent of the Federal Reserve’s own story-like account of economic activity, called the “Beige Book” after the hue of its cover, which is released every six weeks. So, this perhaps could be dubbed the “Buffett Book.” (…)

A housing recovery will probably begin within a year or so. In any event, it is certain to occur at some point. […] These businesses entered the recession strong and will exit it stronger. At Berkshire, our time horizon is forever. (…)

…the third best investment I ever made was the [$31,500] purchase of my home, though I would have made far more money had I instead rented and used the purchase money to buy stocks. (The two best investments were wedding rings.) (…)

IIn a nine-hour period [last year], we sold 1,053 pairs of Justin boots, 12,416 pounds of See’s candy, 8,000 Dairy Queen blizzards, and 8,800 Quikut knives (that’s 16 knives per minute). But you can do better. Remember: Anyone who says money can’t buy happiness simply hasn’t learned to shop.

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

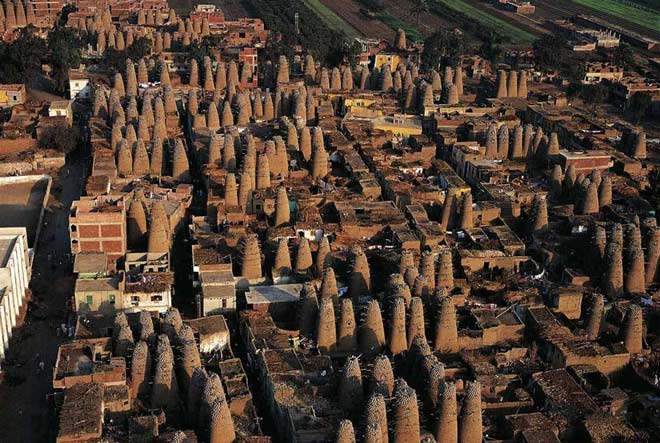

photo { Yann Arthus-Bertrand, Pigeon Houses, Mit Gahmr Delta, Egypt | Thanks Daniel }

more { Critical Analysis of Buffett’s Annual Letter | Aleph blog }

economics, haha, housing | February 28th, 2011 12:20 pm

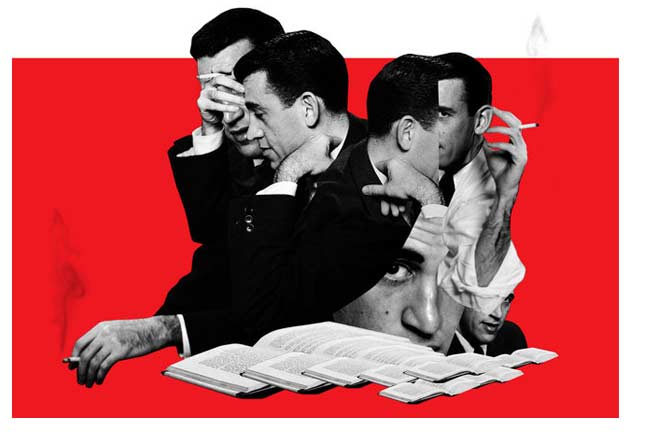

Stanford Graduate School of Business professor Alan Sorenson and Wharton Business School professor Jonah Berger studied an unexpected question: “Can bad publicity boost book sales?”

They discovered that a popular author’s books can suffer from bad publicity, but a lesser-known writer’s titles can actually benefit from it.

{ GalleyCat | Continue reading }

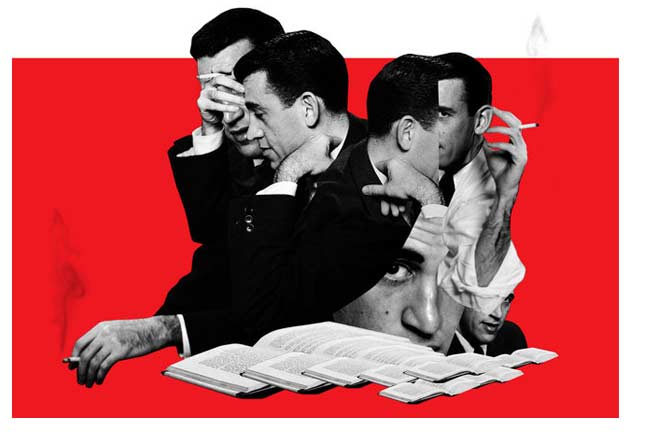

illustration { Paul Sahre }

books, economics, marketing | February 25th, 2011 9:34 am

Most of my interest in the use of biology in economics concerns humans being subject to the forces of selection like any other biological organism. With this starting point, it is natural to pull across many of the tools, models and methods of analysis that evolutionary biologists use.

Sometimes those models and tools are of value without the biological underpinnings. Evolutionary economics is one of the major areas where this is done, with the concepts of selection applied at the level of firms.

Another instance of this crossover was in an article published three weeks ago by Andrew Haldane and Robert May, who have proposed that analysis of complexity and stability in ecosystems (dating from the 1970s) is of some use in examining financial systems.

{ Evolving Economics | Continue reading }

photo { Justin Fantl }

economics, science | February 22nd, 2011 5:41 pm

In a recent talk, John Hagel pointed out that the average life expectancy of a company in the S&P 500 has dropped precipitously, from 75 years (in 1937) to 15 years in a more recent study. Why is the life expectancy of a company so low? And why is it dropping?

I believe that many of these companies are collapsing under their own weight. As companies grow they invariably increase in complexity, and as things get more complex they become more difficult to control.

The statistics back up this assumption. A recent analysis in the CYBEA Journal looked at profit-per-employee at 475 of the S&P 500, and the results were astounding: As you triple the number of employees, their productivity drops by half. (…)

THE COMPANY AS A MACHINE

Historically, we have thought of companies as machines, and we have designed them like we design machines. A machine typically has the following characteristics:

1. It’s designed to be controlled by a driver or operator.

2. It needs to be maintained, and when it breaks down, you fix it.

3. A machine pretty much works in the same way for the life of the machine. Eventually, things change, or the machine wears out, and you need to build or buy a new machine.

(…)

THE COMPANY AS AN ORGANISM

Companies are not so much machines as complex, dynamic, growing systems. As they get larger, acquiring smaller companies, entering into joint ventures and partnerships, and expanding overseas, they become “systems of systems” that rival nation-states in scale and reach.

{ Dave Gray | Continue reading }

image { Victor Faccinto, Sound Box #4, 1995 | Sound sculpture }

economics, ideas | February 22nd, 2011 4:19 pm

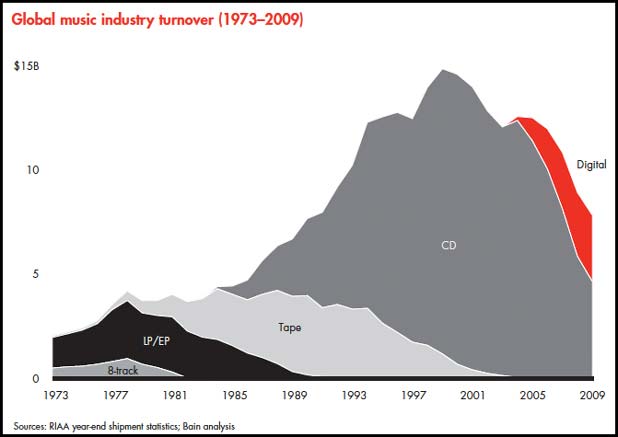

economics, music | February 22nd, 2011 4:15 pm

The 3-6-3 rule describes how bankers would give 3% interest on depositors’ accounts, lend the depositors money at 6% interest and then be playing golf at 3pm.

{ Investopedia | Continue reading }

artwork { Donald Judd, Untitled, 1985 | Donald Judd: Works in Granite, Cor-ten, Plywood, and Enamel on Aluminum at The Pace Gallery, 534 W 25th St, NYC, through Mar 26, 2011 }

Linguistics, economics | February 22nd, 2011 10:47 am

Ms. Brown won acceptance to Oxford at 16. (…)

At 25, she took over the Tatler of London and quickly quadrupled its circulation. At 30, she was in New York running Vanity Fair. She supercharged the magazine with her signature high-low sensibility, which created a template for the magazine that defines it to this day. It was Ms. Brown who hired Annie Leibovitz, often at exorbitant cost, to shoot indelible images. (…)

Her success in reviving Vanity Fair impressed Condé Nast’s chairman, S. I. Newhouse Jr., so much, he asked her to take over his cherished New Yorker in 1992. (…)

Ms. Brown has a salary in the $700,000 range, according to one person briefed on her negotiations with Mr. Harman. Mr. Harman declined to comment. That amount is not wildly high for an editor with as high a profile as Ms. Brown’s.

Holding costs down is one thing. Turning a profit is another. And Ms. Brown’s magazines have generally proven better at spending money than earning it.

The New Yorker broke into the black in 2002, four years after she left but also for the first time since Condé Nast bought it in 1985. Ms. Brown points out that the magazine’s losses had slowed significantly by the time she left.

At Vanity Fair, Ms. Brown had a reputation for spending lavishly on writers and photographers, expenses that put the magazine deeply in debt. But in her final years as editor, it began to turn a profit, though not every year, according to one person with knowledge of Vanity Fair’s business. (…)

Whether The Daily Beast has been the success that Ms. Brown had hoped it would be is a matter of some debate. It initially lost about $10 million a year, but executives said that advertising had picked up in the last year and that they expected profitability “in the next few years,” according to Stephen Colvin, chief executive of the Newsweek Daily Beast Company. Unique visitors to the site have leveled off in the range of two million to three million a month over the last year, according to comScore, the Internet traffic research firm.

The task of taking two money-losing operations and combining them to try to become one profitable enterprise has struck many in the media business as fanciful.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

economics, media, press | February 21st, 2011 10:11 am

economics, music | February 15th, 2011 8:51 pm

Pretend for a moment that you are Google’s search engine.

Someone types the word “dresses” and hits enter. What will be the very first result? There are, of course, a lot of possibilities. Macy’s comes to mind. Maybe a specialty chain, like J. Crew or the Gap. Perhaps a Wikipedia entry on the history of hemlines.

O.K., how about the word “bedding”? Bed Bath & Beyond seems a candidate. Or Wal-Mart, or perhaps the bedding section of Amazon.com.

“Area rugs”? Crate & Barrel is a possibility. Home Depot, too, and Sears, Pier 1 or any of those Web sites with “area rug” in the name, like arearugs.com.

You could imagine a dozen contenders for each of these searches. But in the last several months, one name turned up, with uncanny regularity, in the No. 1 spot for each and every term:

J. C. Penney.

The company bested millions of sites — and not just in searches for dresses, bedding and area rugs. For months, it was consistently at or near the top in searches for “skinny jeans,” “home decor,” “comforter sets,” “furniture” and dozens of other words and phrases, from the blandly generic (“tablecloths”) to the strangely specific (“grommet top curtains”).

The New York Times asked an expert in online search, Doug Pierce of Blue Fountain Media in New York, to study this question, as well as Penney’s astoundingly strong search-term performance in recent months. What he found suggests that the digital age’s most mundane act, the Google search, often represents layer upon layer of intrigue. And the intrigue starts in the sprawling, subterranean world of “black hat” optimization, the dark art of raising the profile of a Web site with methods that Google considers tantamount to cheating.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

painting { Franzikus Wendels, In freier Wildbahn 2, 2007/08 }

economics, google, technology | February 14th, 2011 5:52 pm

housing, photogs | February 14th, 2011 4:00 pm