‘Give me love, give me all that you’ve got.’ –Cerrone

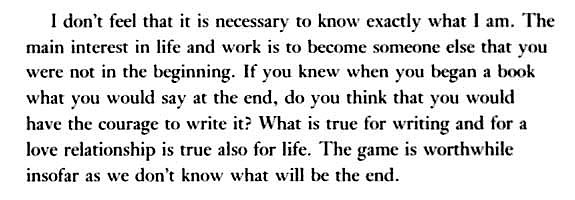

What is sadness? What is anger? What is fear? Are they just words or is there something more? In principle, sadness, anger, and fear are emotions, and so is love. In general, it is usually considered that emotions are natural body-experiences that are then expressed through language and that language, in turn, is often described as irrational and subjective. That is, what we first feel in our bodies, later comes out of our mouths in the form of a discourse which is, in some way, opposed to reason.

Emotions are also said to be gestated in the unconscious and not in the will. Thus, they are more spontaneous than artificial. They are more “sincere” than “thinking”. Sometimes they are mixed with rational behaviors, whose existential status belongs to the order of the non-emotional. Recently, emotions have been considered not as the exclusive preservation of the individual’s interiority, but as discursive social constructions. Indeed, the social Psychology of emotions has shown that the processes, causes, and consequences of emotions depend on language use.

Thus, we will deal with the close relationship between emotions and language. Especially, we will deal with an emotion that has been, in the history of mankind in the Western culture, really important. We refer to “love”, understood in the broadest sense. Love has helped to define the essence of human beings.

“There are some who never would have loved if they never had heard it spoken of”, said La Rochefoucauld. Without a history of love and lovers, we would know nothing on how to cope with such a fundamental emotion as well as on why this particular emotion has been investigated in its various aspects and the strength of the interest when it comes to the relationship between emotions and language.

{ What is love? Discourse about emotions and social sciences | PDF | Continue reading }

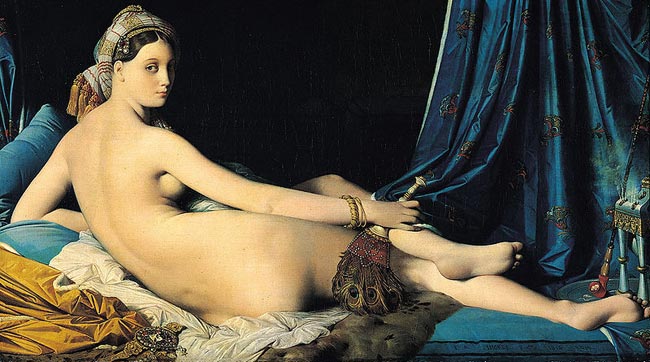

artwork { Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814 }