‘The human mind has no knowledge of the body, and does not know it to exist, save through the ideas of the modifications whereby the body is affected.’ –Spinoza

The brain has long enjoyed a privileged status as psychology’s favorite body organ. This is, of course, unsurprising given that the brain instantiates virtually all mental operations, from understanding language, to learning that fire is dangerous, to recalling names, to categorizing fruits and vegetables, to predicting the future. Arguing for the importance of the brain in psychology is like arguing for the importance of money in economics.

More surprising, however, is the role of the entire body in psychology and the capacity for body parts inside and out to influence and regulate the most intimate operations of emotional and social life. The stomach’s gastric activity , for example, corresponds to how intensely people experience feelings such as happiness and disgust. The hands’ manipulation of objects that vary in temperature and texture influences judgments of how “warm” or “rough” people are. And the ovaries and testes’ production of progesterone and testosterone shapes behavior ranging from financial risk-taking to shopping preferences.

Psychology’s recognition of the body’s influence on the mind coincides with a recent focus on the role of the heart in our social psychology. It turns out that the heart is not only critical for survival, but also for how people related to one another.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

One of the pressing questions in seventeenth century philosophy, and perhaps the most celebrated legacy of Descartes’s dualism, is the problem of how two radically different substances such as mind and body enter into a union in a human being and cause effects in each other. How can the extended body causally engage the unextended mind, which is incapable of contact or motion, and “move” it, that is, cause mental effects such as pains, sensations and perceptions.

Spinoza, in effect, denies that the human being is a union of two substances. The human mind and the human body are two different expressions—under Thought and under Extension—of one and the same thing: the person. And because there is no causal interaction between the mind and the body, the so-called mind-body problem does not, technically speaking, arise.

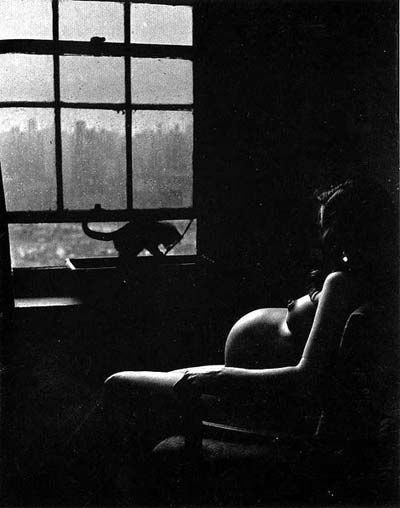

photo { Philippe Halsman }