ideas

Two theoretical frameworks have been proposed to account for the representation of truth and falsity in human memory: the Cartesian model and the Spinozan model. Both models presume that during information processing a mental representation of the information is stored along with a tag indicating its truth value. However, the two models disagree on the nature of these tags. According to the Cartesian model, true information receives a “true” tag and false information receives a “false” tag. In contrast, the Spinozan model claims that only false information receives a “false” tag, whereas untagged information is automatically accepted as true. […]

The results of both experiments clearly contradict the Spinozan model but can be explained in terms of the Cartesian model.

{ Memory & Cognition | PDF }

art { Richard Long, Dusty Boots Line, The Sahara, 1988 }

neurosciences, spinoza | July 8th, 2018 9:42 am

Linguistics | May 17th, 2018 2:00 pm

ideas, leisure | April 23rd, 2018 5:58 am

Let’s begin with a simple fact: time passes faster in the mountains than it does at sea level. The difference is small but can be measured with precision timepieces that can be bought today for a few thousand pounds. This slowing down can be detected between levels just a few centimetres apart: a clock placed on the floor runs a little more slowly than one on a table.

It is not just the clocks that slow down: lower down, all processes are slower. Two friends separate, with one of them living in the plains and the other going to live in the mountains. They meet up again years later: the one who has stayed down has lived less, aged less, the mechanism of his cuckoo clock has oscillated fewer times. He has had less time to do things, his plants have grown less, his thoughts have had less time to unfold … Lower down, there is simply less time than at altitude. […]

Times are legion: a different one for every point in space. The single quantity “time” melts into a spiderweb of times.

{ Guardian | Continue reading }

photo { Julie Blackmon }

time | April 16th, 2018 9:29 am

With a few minor exceptions, there are really only two ways to say “tea” in the world. One is like the English term—té in Spanish and tee in Afrikaans are two examples. The other is some variation of cha, like chay in Hindi.

Both versions come from China. How they spread around the world offers a clear picture of how globalization worked before “globalization” was a term anybody used. The words that sound like “cha” spread across land, along the Silk Road. The “tea”-like phrasings spread over water, by Dutch traders bringing the novel leaves back to Europe.

{ Quartz | Continue reading }

art { Josef Albers, Interaction of Color, 1963 }

Linguistics, food, drinks, restaurants | February 16th, 2018 12:34 pm

Here, we analysed 200 million online conversations to investigate transmission between individuals. We find that the frequency of word usage is inherited over conversations, rather than only the binary presence or absence of a word in a person’s lexicon. We propose a mechanism for transmission whereby for each word someone encounters there is a chance they will use it more often. Using this mechanism, we measure that, for one word in around every hundred a person encounters, they will use that word more frequently. As more commonly used words are encountered more often, this means that it is the frequencies of words which are copied.

{ Journal of the Royal Society Interface | Continue reading }

Linguistics | February 15th, 2018 1:11 pm

Grapheme-color synesthesia is a neurological phenomenon in which viewing a grapheme elicits an additional, automatic, and consistent sensation of color.

Color-to-letter associations in synesthesia are interesting in their own right, but also offer an opportunity to examine relationships between visual, acoustic, and semantic aspects of language. […]

Numerous studies have reported that for English-speaking synesthetes, “A” tends to be colored red more often than predicted by chance, and several explanatory factors have been proposed that could explain this association.

Using a five-language dataset (native English, Dutch, Spanish, Japanese, and Korean speakers), we compare the predictions made by each explanatory factor, and show that only an ordinal explanation makes consistent predictions across all five languages, suggesting that the English “A” is red because the first grapheme of a synesthete’s alphabet or syllabary tends to be associated with red.

We propose that the relationship between the first grapheme and the color red is an association between an unusually-distinct ordinal position (”first”) and an unusually-distinct color (red).

{ Cortex | Continue reading }

A Black, E white, I red, U green, O blue: vowels,

Someday I shall tell of your mysterious births

{ Arthur Rimbaud | Continue reading }

art { Roland Cat, The pupils of their eyes, 1985 }

Linguistics, colors, neurosciences | February 12th, 2018 1:27 pm

If you write clearly, then your readers may understand your mathematics and conclude that it isn’t profound. Worse, a referee may find your errors. Here are some tips for avoiding these awful possibilities.

1. Never explain why you need all those weird conditions, or what they mean. For example, simply begin your paper with two pages of notations and conditions without explaining that they mean that the varieties you are considering have zero-dimensional boundary. In fact, never explain what you are doing, or why you are doing it. The best-written paper is one in which the reader will not discover what you have proved until he has read the whole paper, if then

2. Refer to another obscure paper for all the basic (nonstandard) definitions you use, or never explain them at all. This almost guarantees that no one will understand what you are talking about

[…]

11. If all else fails, write in German.

{ J.S. Milne | Continue reading }

photos { Left: William Henry Jackson, Pike’s Peak from the Garden of the Gods, Colorado Midland Series, ca.1880 | Right: Ye Rin Mok }

guide, ideas, mathematics | January 25th, 2018 1:37 pm

I argue that the state of boredom (i.e., the transitory and non-pathological experience of boredom) should be understood to be a regulatory psychological state that has the capacity to promote our well-being by contributing to personal growth and to the construction (or reconstruction) of a meaningful life.

{ Philosophical Psychology }

oil on canvas { Piet Mondrian, Composition in Black and White, with Double Lines, 1934 }

ideas | January 25th, 2018 1:05 pm

Several temporal paradoxes exist in physics. These include General Relativity’s grandfather and ontological paradoxes and Special Relativity’s Langevin-Einstein twin-paradox. General relativity paradoxes can exist due to a Gödel universe that follows Gödel’s closed timelike curves solution to Einstein’s field equations.

A novel biological temporal paradox of General Relativity is proposed based on reproductive biology’s phenomenon of heteropaternal fecundation. Herein, dizygotic twins from two different fathers are the result of concomitant fertilization during one menstrual cycle. In this case an Oedipus-like individual exposed to a Gödel closed timelike curve would sire a child during his maternal fertilization cycle.

As a consequence of heteropaternal superfecundation, he would father his own dizygotic twin and would therefore generate a new class of autofraternal superfecundation, and by doing so creating a ‘twin-father’ temporal paradox.

{ Progress in Biophysics & Molecular Biology | Continue reading }

ideas, time | January 22nd, 2018 3:23 pm

More recently we have supertasks such as Benardete’s Paradox of the Gods,

A man decides to walk one mile from A to B. A god waits in readiness to throw up a wall blocking the man’s further advance when the man has travelled ½ a mile. A second god (unknown to the first) waits in readiness to throw up a wall of his own blocking the man’s further advance when the man has travelled ¼ mile. A third god … etc. ad infinitum. (Benardete 1964, pp. 259-60)

Since for any place after A, a wall would have stopped him reaching it, the traveller cannot move from A. The gods have kept him still without ever raising a wall. Yet how could they cause him to stay still without causally interacting with him? Only a wall can stop him and no wall is ever raised, since for each wall he must reach it for it to be raised but he would have been stopped at an earlier wall. So he can move from A.

[…]

In the Nothing from Infinity paradox we will see an infinitude of finite masses and an infinitude of energy disappear entirely, and do so despite the conservation of energy in all collisions. I then show how this leads to the Infinity from Nothing paradox, in which we have the spontaneous eruption of infinite mass and energy out of nothing. […]

{ European Journal for Philosophy of Science | Continue reading }

photo { Alex Prager, Crowd #2 (Emma), 2012 }

ideas | January 19th, 2018 3:56 pm

Whereas women of all ages prefer slightly older sexual partners, men—regardless of their age—have a preference for women in their 20s. Earlier research has suggested that this difference between the sexes’ age preferences is resolved according to women’s preferences. This research has not, however, sufficiently considered that the age range of considered partners might change over the life span.

Here we investigated the age limits (youngest and oldest) of considered and actual sex partners in a population-based sample of 2,655 adults (aged 18-50 years). Over the investigated age span, women reported a narrower age range than men and women tended to prefer slightly older men. We also show that men’s age range widens as they get older: While they continue to consider sex with young women, men also consider sex with women of their own age or older.

Contrary to earlier suggestions, men’s sexual activity thus reflects also their own age range, although their potential interest in younger women is not likely converted into sexual activity. Homosexual men are more likely than heterosexual men to convert a preference for young individuals into actual sexual behavior, supporting female-choice theory.

{ Evolutionary Psychology | PDF }

related { Longest ever personality study finds no correlation between measures taken at age 14 and age 77 }

photo { Joan Crawford photographed by George Hurrell, 1932 }

relationships, time | February 7th, 2017 12:53 pm

Postmodernism has, to a large extent, run its course [despite having made the considerable innovation of presenting] the first text that was highly self-conscious, self-conscious of itself as text, self-conscious of the writer as persona, self-conscious about the effects that narrative had on readers and the fact that the readers probably knew that. […] A lot of the schticks of post-modernism — irony, cynicism, irreverence — are now part of whatever it is that’s enervating in the culture itself.

{ David Foster Wallace | Continue reading }

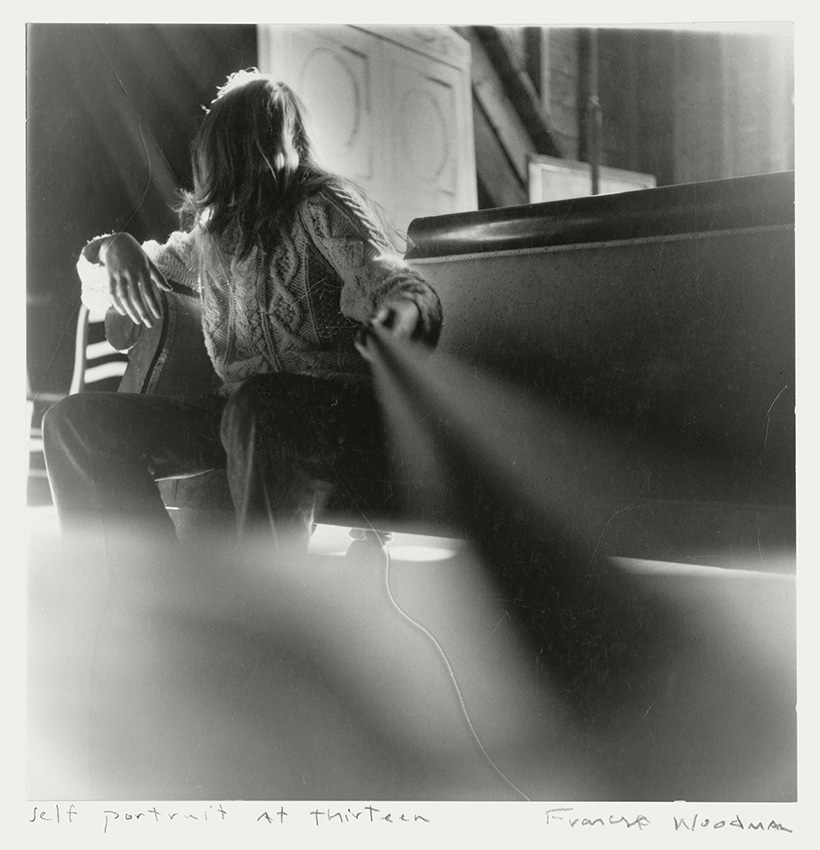

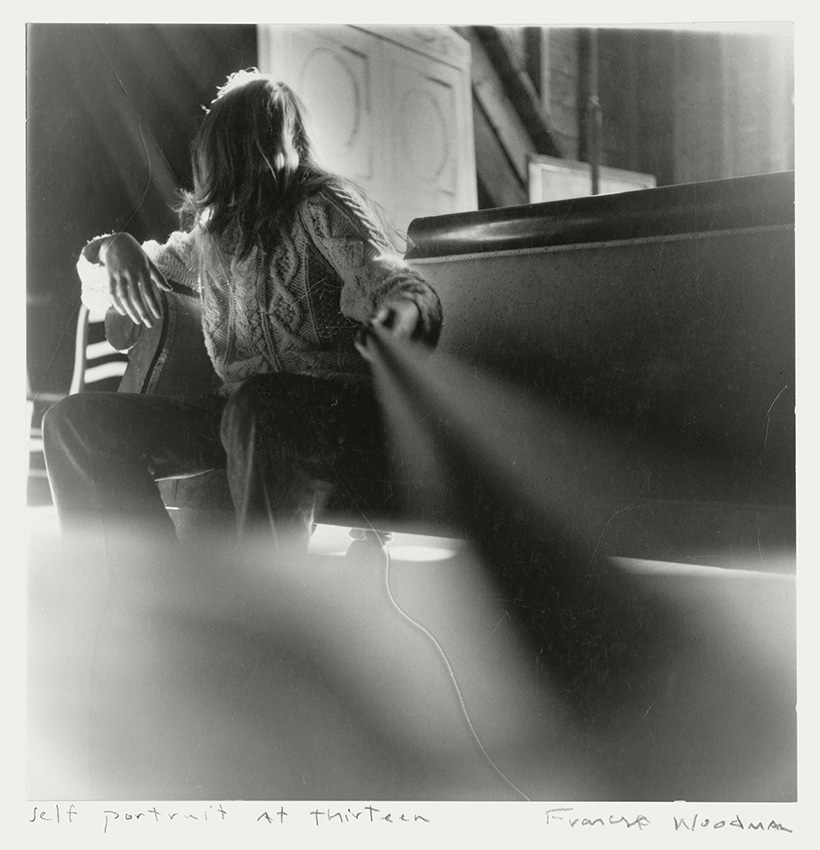

photo { Francesca Woodman, Self-portrait at 13, Boulder, Colorado, 1972 | Photography tends not to have prodigies. Woodman, who committed suicide in 1981 at age 22, is considered a rare exception. | NY Review of Books | full story }

ideas, photogs | February 7th, 2017 12:35 pm

This paper approaches the subject of God or a supernatural being that created the universe from a mathematical and physical point of view. It sets up a hypothesis that when the God existed before the Big Bang as an unconscious being became conscious, the energy that was produced during the process became a both highly dense and infinite temperature Cosmic Egg and exploded to create the current universe. This assumption is demonstrated by mathematical formulas and physics law, which provide a solid scientific foundation for the aforementioned theory.

{ International Education and Research Journal | Continue reading }

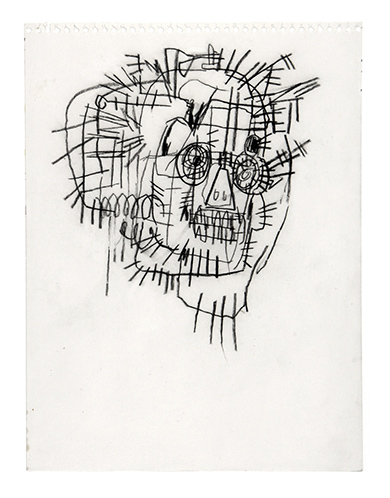

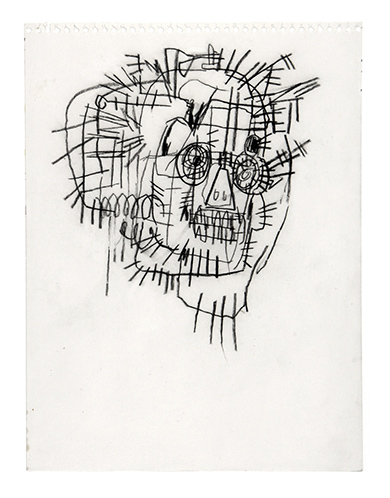

art { Jean-Michel Basquiat, Head, 1981 }

theory | October 31st, 2016 12:47 pm

When used in speech, hesitancies can indicate a pause for thought, when read in a transcript they indicate uncertainty. In a series of experiments the perceived uncertainty of the transcript was shown to be higher than the perceived uncertainty of the spoken version with almost no overlap for any respondent.

{ arXiv | Continue reading }

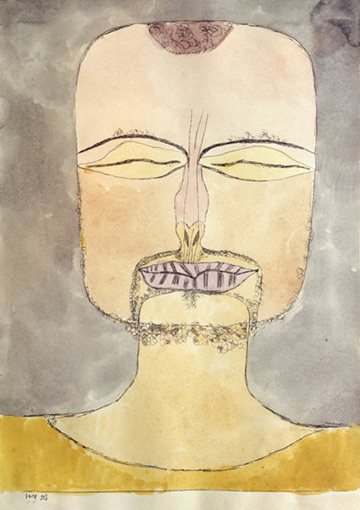

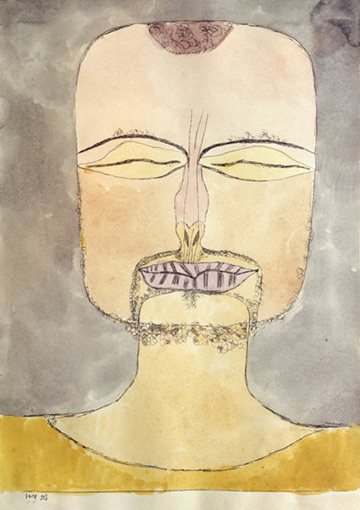

art { Paul Klee, After the drawing 19/75, 1919 }

ideas | September 20th, 2016 7:48 am

For hundreds of years, Koreans have used a different method to count age than most of the world. […] A person’s Korean age goes up a year on new year’s day, not on his or her birthday. So when a baby is born on Dec. 31, he or she actually turns two the very next day.

{ Quartz | Continue reading }

asia, time | September 16th, 2016 8:59 am

Is our perceptual experience a veridical representation of the world or is it a product of our beliefs and past experiences? Cognitive penetration describes the influence of higher level cognitive factors on perceptual experience and has been a debated topic in philosophy of mind and cognitive science.

{ Consciousness and Cognition | Continue reading }

photo { Can you think a thought which isn’t yours? A remarkable new study suggests you can }

ideas, psychology | June 24th, 2016 8:23 am

Cioffi endorses the Oxford comma, the one before and in a series of three or more. On the question of whether none is singular or plural, he is flexible: none can mean not a single one and take a singular verb, or it can mean not any and take a plural verb. His sample “None are boring” (from the New Yorker, where I work) was snipped from a review of a show of photographs by Richard Avedon. Cioffi would prefer the singular in this instance — “None is boring” — arguing that it “emphasizes how not a single, solitary one of these Avedon photographs is boring”. To me, putting so much emphasis on the photos’ not being boring suggests that the critic was hoping for something boring. I would let it stand. […]

“that usually precedes elements that are essential to your sentence’s meaning [restrictive], while which typically introduces ‘nonessential’ elements [non-restrictive], and usually refers to the material directly before it.” Americans sometimes substitute which for that, thinking it makes us sound more proper (i.e. British). On both sides of the Atlantic, the classic nonrestrictive which is preceded by a comma.

{ The Times Literary Supplement | Continue reading }

Linguistics | June 13th, 2016 11:30 am

The publication of Richard Krafft-Ebbing’s masterwork Psychopathia Sexualis in 1886 represented a landmark in thinking about human sexuality and the bizarre forms that it can take. In addition to describing different types of sexual expression that the author regarded as “perverse” (usually any form of sex that didn’t lead to procreation), it quickly became one of the most influential books on human sexuality ever written and introduced numerous new terms into common usage. One of these terms was “masochism,” which Krafft-Ebbing defined as the opposite of sadism (which he also coined). While the later is the desire to cause pain and use force, the former is the wish to suffer pain and be subjected to force.

one person in particular who was less than pleased with the new term was the Austrian author, Leopold von Sacher-Masoch. Krafft-Ebbing justified naming this new sexual anomaly after the prominent author whom he described as “the poet of Masochism” due to his erotic writings and because of his own eccentric personal life. […]

Venus in Furs, the short novel for which Sacher-Masoch is best known, was published in 1870, and has become an erotic classic in its own right. In this book, the hero Severin asks to be treated as a slave and to be abused by Wanda (the “Venus in furs” of the story). The fact that Sacher-Masoch often acted out these fantasies in real-life with his wives and mistresses was not well-known. […]

It may be a coincidence that his health went into a decline shortly after Psychopathia Sexualis came out but by March of 1895, he was delusional and violent. After attempting to kill his then-wife Hulda, she arranged for him to be discreetly moved to an asylum in Lindheim, Hesse. Although his official obituary states that he died that year, there are claims that Sacher-Masoch lived on as an anonymous asylum inmate and actually died years later.

{ Providentia | Continue reading }

Onomastics, flashback, psychology | June 13th, 2016 11:20 am

With tens or even hundreds of billions of potentially habitable planets within our galaxy, the question becomes: are we alone?

Many scientists and commentators equate “more planets” with “more E.T.s”. However, the violence and instability of the early formation and evolution of rocky planets suggests that most aliens will be extinct fossil microbes.

Just as dead dinosaurs don’t walk, talk or breathe, microbes that have been fossilised for billions of years are not easy to detect by the remote sampling of exoplanetary atmospheres.

In research published [PDF] in the journal Astrobiology, we argue that early extinction could be the cosmic default for life in the universe. This is because the earliest habitable conditions may be unstable. […] Inhabited planets may be rare in the universe, not because emergent life is rare, but because habitable environments are difficult to maintain during the first billion years.

Our suggestion that the universe is filled with dead aliens might disappoint some, but the universe is under no obligation to prevent disappointment.

{ The Conversation | Continue reading }

previously { Where is the Great Filter? Behind us, or not behind us? If the filter is in our past, there must be some extremely improbable step in the sequence of events whereby an Earth-like planet gives rise to an intelligent species comparable in its technological sophistication to our contemporary human civilization. }

still { The Day the Earth Stood Still, 1951 }

ideas, mystery and paranormal, space | June 8th, 2016 10:59 am