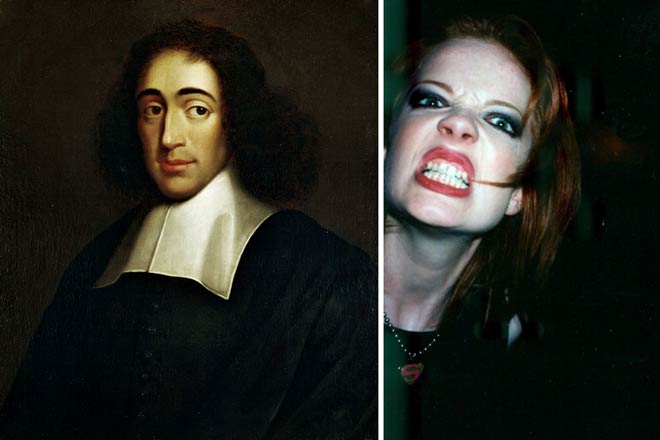

Bento was the name Spinoza received at his birth from his parents, Miguel and Hana Debora, Portuguese Sephardic Jews who had resettled in Amsterdam. He was known as Baruch in the synagogue and among friends while he was growing up in Amsterdam’s affluent community of Jewish merchants and scholars. He adopted the name Benedictus at age twenty-four after he was banished by the synagogue. Spinoza abandoned the comfort of his Amsterdam family home and began the calm and deliberate errancy whose last stop was here in the Paviljoensgracht. The Portuguese name Bento, the Hebrew name Baruch, and the Latin name Benedictus, all mean the same: blessed. So, what’s in a name? Quite a lot, I would say. The words may be superficially equivalent, but the concept behind each of them was dramatically different. (…)

I also can imagine a funeral cortege, on another gray day, February 25, 1677, Spinoza’s simple coffin, followed by the Van der Spijk family, and “many illustrious men, six carriages in all,” marching slowly to the New Church, just minutes away. I walk back to the New Church retracing their likely route. I know Spinoza’s grave is in the churchyard, and from the house of the living I may as well go to the house of the dead.

Gates surround the churchyard but they are wide open. There is no cemetery to speak of, only shrubs and grass and moss and muddy lanes amid the tall trees. I find the grave much where I thought it would be, in the back part of the yard, behind the church, to the south and east, a flat stone at ground level and a vertical tombstone, weathered and unadorned.

Besides announcing whose grave it is, the inscription reads CAUTE! which is Latin for “Be careful!” This is a chilling bit of advice considering Spinoza’s remains are not really inside the tomb, and that his body was stolen, no one knows by whom, sometime after the burial when the corpse lay inside the church. Spinoza had told us that every man should think what he wants and say what he thinks, but not so fast, not quite yet. Be careful. Watch out for what you say (and write) or not even your bones will escape.

{ Antonio Damasio, Looking for Spinoza, 2003 | Continue reading | Amazon }

Spinoza could not be buried in the Jewish cemetery in The Hague as a cherem (boycott) had been imposed on him by the Jewish community of Amsterdam. In the summer of 1956, 279 years later, his admirers erected a basalt tombstone behind the church with a portrait of Spinoza and the Hebrew word “עַמך” (amcha) meaning “your people” on it. The Jewish community of Amsterdam was represented by Georg Herz-Shikmoni, a sign that Spinoza was once again recognized as a member of the community.

The Latin inscription on a stone slab laid in the ground in front of the tombstone reads “Terra hic Benedicti de Spinoza in Ecclesia Nova olim sepulti ossa tegit” and means “The earth here covers the bones of Benedict de Spinoza, long interred in the New Church”.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }