|

|

|

Sense-perception—the awareness or apprehension of things by sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste—has long been a preoccupation of philosophers. One pervasive and traditional problem, sometimes called “the problem of perception”, is created by the phenomena of perceptual illusion and hallucination: if these kinds of error are possible, how can perception be what it intuitively seems to be, a direct and immediate access to reality? The present entry is about how these possibilities of error challenge the intelligibility of the phenomenon of perception, and how the major theories of perception in the last century are best understood as responses to this challenge.

{ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy | Continue reading }

Phenomenology is the study of structures of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view. The central structure of an experience is its intentionality, its being directed toward something, as it is an experience of or about some object. An experience is directed toward an object by virtue of its content or meaning (which represents the object) together with appropriate enabling conditions.

Phenomenology as a discipline is distinct from but related to other key disciplines in philosophy, such as ontology, epistemology, logic, and ethics. Phenomenology has been practiced in various guises for centuries, but it came into its own in the early 20th century in the works of Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty and others. Phenomenological issues of intentionality, consciousness, qualia, and first-person perspective have been prominent in recent philosophy of mind. (…)

The Oxford English Dictionary presents the following definition: “Phenomenology. a. The science of phenomena as distinct from being (ontology). b. That division of any science which describes and classifies its phenomena. From the Greek phainomenon, appearance.” In philosophy, the term is used in the first sense, amid debates of theory and methodology. In physics and philosophy of science, the term is used in the second sense, albeit only occasionally.

{ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy | Continue reading }

Linguistics, ideas |

July 1st, 2011

{ There are about 2,000 species of fireflies, a type of beetle that lights up its abdomen with a chemical reaction to attract a mate. That glow can be yellow, green or pale-red. In some places the firefly dance is synchronized, with the insects flashing in unison or in waves. The lightshow has also been beneficial to science—researchers have found that the chemical responsible for it, luciferase, is a useful marker in a variety of applications, including genetic engineering and forensics. | Smithsonian magazine | full article }

insects, science |

July 1st, 2011

First impressions are important, and they usually contain a healthy dose both of accuracy and misperception. But do people know when their first impressions are correct? They do reasonably well, according to a recent study.

Sometimes after meeting a person for the first time, there is a strong sense that you really understand him or her—you immediately feel as if you could predict his or her behavior in a variety of situations, and you feel that even your first impression would agree with those of others who know that person well. That is, your impression feels realistically accurate (Funder, 1995, 1999). Other times, you leave an interaction feeling somewhat unsure about how accurate your impression is—it is not clear how that individual would behave in different situations or what his or her close friends and family members would say about him or her. Are such intuitions about the realistic accuracy of one’s impressions valid? That is, do people know when they know? The current studies address this question by examining the extent to which people have accuracy awareness—an understanding of whether their first impressions of others’ personalities are realistically accurate.

{ Social Psychological and Personality Science | Continue reading }

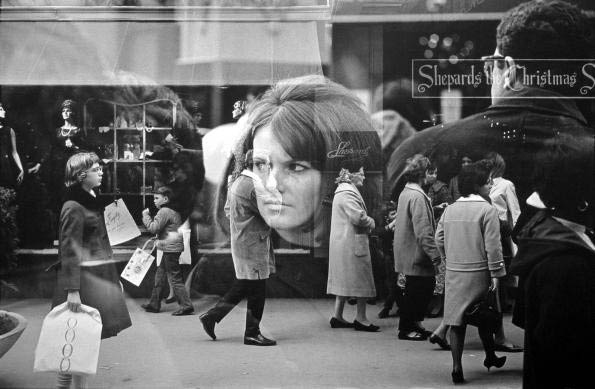

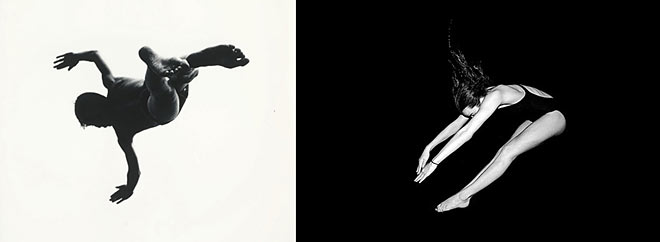

photo { Harry Callahan }

psychology, relationships |

July 1st, 2011

Enthusiasm for The Wire is hardly limited to law professors, but the series does seem to hold a special appeal for us, especially if we teach criminal law and criminal procedure. What accounts for that appeal? Not, I think, the widely praised realism of The Wire, at least not in the most obvious ways. The series does have an almost visceral sense of place, and it does show, in grim detail, many of the ways the criminal justice system goes wrong. But the loving attention to Baltimore does little to explain the particular pull the series has for those of us who teach and write about criminal justice, and the institutional failures that the series spotlights—the futility of the war on drugs, the cooking of crime statistics, the often casual brutality of street-level policing—are, let’s face it, hardly news. Even among law professors, it’s hard to imagine any documentary about those failures, no matter how accurate, generating the kind of excitement The Wire has generated.

It has to be said, too, that there are important ways in which The Wire isn’t all that realistic. It is not particularly good, for example, at capturing the workaday feel of law enforcement. Any number of less celebrated television programs—Barney Miller, Cagney & Lacey, Hill Street Blues, even Law & Order—have done a better job of that. Nor, for the most part, does The Wire seem especially perceptive about leadership. The organizational dynamics of law enforcement, and the compromised politics of city government, often have a crazed, over-the-top feel in the series—entertaining, but not strikingly true to life. In these respects, and some others, The Wire aims less for verisimilitude than for the power of myth.

Nonetheless much of what makes The Wire so gripping—and, I think, much of what makes it especially gripping for professors of criminal law and criminal procedure—does seem to have to do with a certain kind of realism. It isn’t detailed accuracy about institutional failures, or the drug trade, or post-9/11 Baltimore, but something at once bigger and more basic: the dimensions of human and moral complexity that criminal justice work, in pretty much any time or place, will inevitably bring to the surface.

{ David Alan Sklansky, Confined, Crammed, and Inextricable: What The Wire Gets Right, 2011 | SSRN | Continue reading }

ideas, showbiz |

July 1st, 2011

Each culture has its agreed-upon list of taboo words and it doesn’t matter how many times these words are repeated, they still seem to retain their power to shock. Scan a human brain, swear at it, and you’ll see its emotional centres jangle away.

Recent research has shown that this emotional impact can have an analgesic effect, and there’s other evidence that strategically deployed swear words can make a speech more memorable. But it’s not all positive. A new study suggests that swear words have a dark side. Megan Robbins and her team recorded snippets of speech from middle-aged women with rheumatoid arthritis, and others with breast cancer, and found those who swore more in the company of other people also experienced increased depression and a perceived loss of social support.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

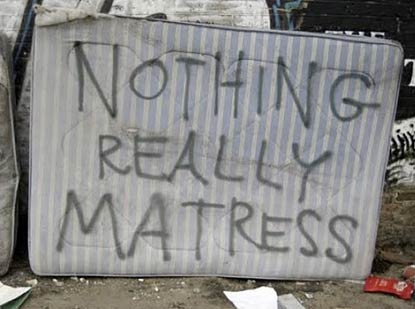

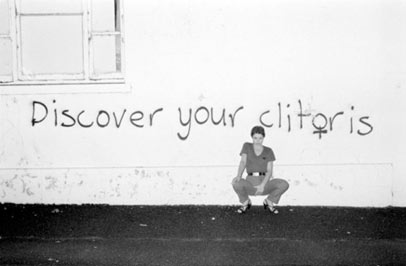

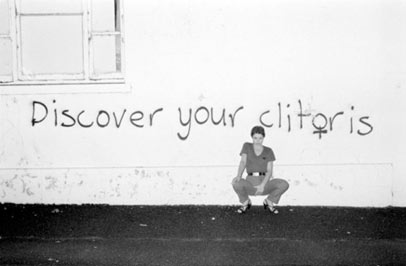

photo { Calvin Sawer }

Linguistics, health, psychology |

July 1st, 2011

One way to study a network is to break it down into its simplest pattern of links. These simple patterns are called motifs and their numbers usually depend on the type of network.

One of the big puzzles of network science is that some motifs crop up much more often than others. These motifs are clearly important. Remove them (or change their distribution) and the behaviour of the network changes too. But nobody knows why.

Today, Xiao-Ke Xu at Hong Kong Polytechnic University and friends say they know why and the answer is intimately linked to the existence of rich clubs within a network.

Let’s step back for a bit of background. In many networks, a small number of nodes are well connected to large number of others. The group of all well-connected nodes is known as the “rich club” and it is known to play an important role in the network of which it is part.

Rich clubs are particularly influential in a specific class of network in which the number of links between nodes varies in a way that is scale free (ie follows a power law).

This is an important class. It includes the internet, social networks, airline networks and many naturally occurring networks such as gene regulatory networks.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

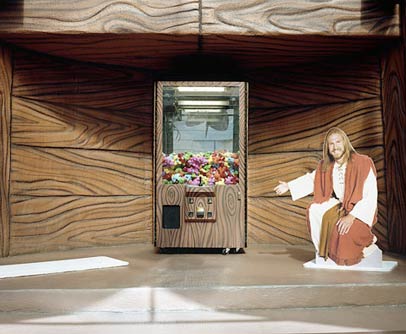

photo { Jimi Franklin }

ideas, science, technology |

July 1st, 2011

cats, photogs, taxidermy |

July 1st, 2011

On 26 September 1991, eight “bionauts,” as they called themselves, wearing identical red Star Trek–like jumpsuits (made for them by Marilyn Monroe’s former dressmaker) waved to the assembled crowd and climbed through an airlock door in the Arizona desert. They shut it behind them and opened another that led into a series of hermetically sealed greenhouses in which they would live for the next two years. The three-acre complex of interconnected glass Mesoamerican pyramids, geodesic domes, and vaulted structures contained a tropical rain forest, a grassland savannah, a mangrove wetland, a farm, and a salt-water ocean with a wave machine and gravelly beach. This was Biosphere 2—the first biosphere being Earth—a $150 million experiment designed to see if, in a climate of nuclear and ecological fear, the colonization of space might be possible.

{ Cabinet | Continue reading }

artwork { Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Duel after the Masquerade, 1857 }

flashback, science |

July 1st, 2011

Nortel Networks, the bankrupt Canadian telecom company, came that much closer to disappearing completely yesterday with the cash sale of its portfolio of 6000 patents for $4.5 billion to a consortium of companies including Apple, EMC, Ericsson, Microsoft, Research In Motion (RIM), and Sony. The bidding, which began with a $900 million offer from Google, went far higher than most observers expected and only ended, I’m guessing, when Google realized that Apple and its partners had deeper pockets and would have paid anything to win. This transaction is a huge blow to Google’s Android platform, which was precisely the consortium’s goal.

{ Robert X. Cringely | Continue reading }

economics, technology |

July 1st, 2011

University of Oxford Writing and Style Guide decided that writers should, “as a general rule,” avoid using the Oxford comma.

Here’s an explanation from the style guide: As a general rule, do not use the serial/Oxford comma: so write ‘a, b and c’ not ‘a, b, and c.’

{ GalleyCat | Continue reading }

Linguistics |

July 1st, 2011

The wrinkles that develop on wet fingers could be an adaptation to give us better grip in slippery conditions, the latest theory suggests.

The hypothesis, from Mark Changizi, an evolutionary neurobiologist at 2AI Labs in Boise, Idaho, and his colleagues goes against the common belief that fingers turn prune-like simply because they absorb water.

Changizi thinks that the wrinkles act like rain treads on tyres. They create channels that allow water to drain away as we press our fingertips on to wet surfaces. This allows the fingers to make greater contact with a wet surface, giving them a better grip.

{ Nature | Continue reading }

science |

July 1st, 2011

There are numerous comparisons between Google’s new Google+ social offering and Facebook, but most of them miss the mark. Google knows the social train has left the station and there is a very slim chance of catching up with Facebook’s 750 million active users. However, Twitter’s position as a broadcast platform for 21 million active publishers is a much more achievable goal for Google to reach. (…)

While Facebook is not sweating about Google+, the threat to Twitter is significant. Google has the opportunity to displace Twitter if it gets publishers and celebrities to encourage Google+ follows on their websites as well as pushing posts to the legions of Google users while they are in Search, Gmail and YouTube. Google was turned down when it tried to buy Twitter for $10 billion, and now it is going to try to replicate it.

{ Social Beat | Continue reading }

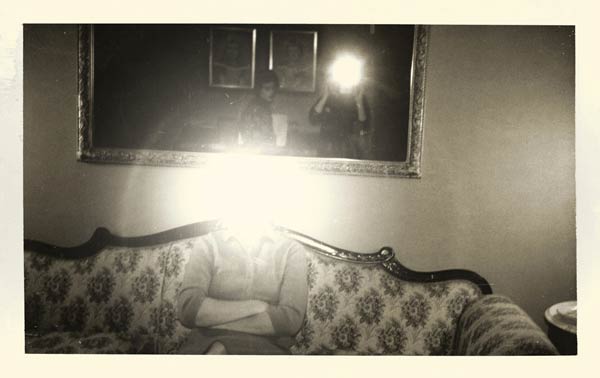

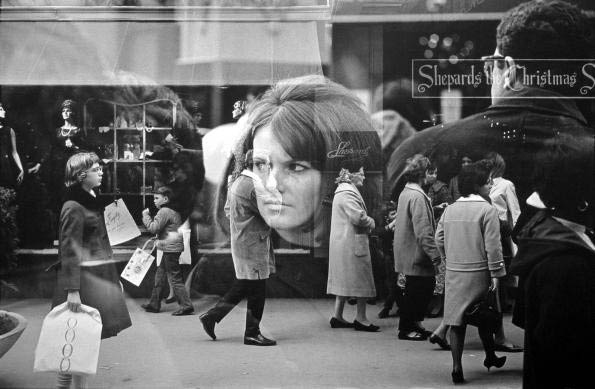

photo { Jay Van Dam }

related { Invite your entire Facebook graph into Google Plus | Searching through other people’s photographs as soon as they’ve taken them is now possible thanks to a new search service. }

economics, google, social networks |

July 1st, 2011

For a long time, the mechanisms of taste seemed relatively straightforward. (…) Ever since Democritus hypothesized in the fourth century B.C. that the sensation of taste was an effect of the shape of food particles, the tongue has been seen as a simple sensory organ. (…) Plato believed Democritus. (…) Aristotle believed Plato. In De Anima, the four primary tastes Aristotle described were the already classic sweet, sour, salty, and bitter.

Over the ensuing millennium, this ancient theory remained largely unquestioned. The tongue was seen as a mechanical sensor, in which the qualities of foods were impressed upon its papillaed surface. The discovery of taste buds in the 19th century gave new credence to this theory. Under a microscope, these cells looked like little keyholes into which our chewed food might fit, thus triggering a taste sensation. By the start of the 20th century, scientists were beginning to map the tongue, consigning each of our four flavors to a specific area. The tip of our tongue loved sweet things, while the sides preferred sour. The back of our tongue was sensitive to bitter flavors, and saltiness was sensed everywhere. The sensation of taste was that simple.

If only. We now know that our taste receptors are exquisitely complicated little sensors, and that there are at least five different receptor types scattered all over the mouth, not four. (The fifth receptor is sensitive to the amino acid glutamate, aka umami.) Furthermore, the tongue is only a small part of flavor: As anyone with a stuffy nose knows, the pleasure of food largely depends on its aroma. In fact, neuroscientists estimate that up to 90 percent of what we perceive as taste is actually smell. (…)

Perhaps the most shocking discovery from this new science of taste, however, is that the act of eating is not the only source of gustatory pleasure. Instead, a big chunk part of our sensory delight — the joy that makes us crave particular foods — comes afterwards, when the food is winding its way through the gut.

{ Wired | Continue reading }

food, drinks, restaurants, science |

June 30th, 2011

animals, photogs |

June 29th, 2011

Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness, the causes of which are not yet well understood. It afflicts about 1% of the population, typically emerging in late adolescence or early adulthood. Neuroimaging and functional testing identify diminished brain volume in key areas and declining cognitive and social functioning at the time that symptoms of the disease emerge. After onset, the symptoms persist, although their intensity fluctuates and some long-term research has identified patients in whom symptoms have dissipated many years after onset. Psychotropic drugs relieve symptoms such as hallucinations and paranoid delusions for some patients, but they have no effect on cognitive or social functioning.

{ Housing and Mental Illness | Harvard University Press | Continue reading }

artwork { Izumi Kato }

health, ideas, neurosciences |

June 29th, 2011

photogs, visual design |

June 29th, 2011

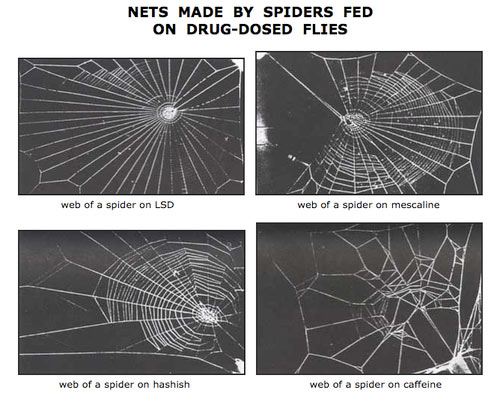

animals, drugs |

June 29th, 2011

We don’t quite understand small probabilities.

You often see in the papers things saying events we just saw should happen every ten thousand years, hundred thousand years, ten billion years. Some faculty here in this university had an event and said that a 10-sigma event should happen every, I don’t know how many billion years.

So the fundamental problem of small probabilities is that rare events don’t show in samples, because they are rare. So when someone makes a statement that this in the financial markets should happen every ten thousand years, visibly they are not making a statement based on empirical evidence, or computation of the odds, but based on what? On some model, some theory.

So, the lower the probability, the more theory you need to be able to compute it. Typically it’s something called extrapolation, based on regular events and you extend something to what you call the tails. (…)

The smaller the probability, the less you observe it in a sample, therefore your error rate in computing it is going to be very high. Actually, your relative error rate can be infinite, because you’re computing a very, very small probability, so your error rate is monstrous and probably very, very small. (…)

There are two kinds of decisions you make in life, decisions that depend on small probabilities, and decisions that do not depend on small probabilities. For example, if I’m doing an experiment that is true-false, I don’t really care about that pi-lambda effect, in other words, if it’s very false or false, it doesn’t make a difference. (…) But if I’m studying epidemics, then the random variable how many people are affected becomes open-ended with consequences so therefore it depends on fat tails. So I have two kinds of decisions. One simple, true-false, and one more complicated, like the ones we have in economics, financial decision-making, a lot of things, I call them M1, M1+.

{ Nassim Nicholas Taleb/Edge | Continue reading }

economics, ideas, mathematics |

June 28th, 2011