science

Forensic scientists of the future may soon have a new tool at their disposal. Given a drop of blood, researchers in the Netherlands have roughly determined the age of the person it came from. But for now, it really is rough–the researchers found they could only estimate a person’s age to within 9 years.

Currently, a crime scene investigator who obtained a spot of blood can check its DNA to see if it matches a known suspect or someone in a law enforcement database, and can use the DNA to determine a few other characteristics like gender and eye color. But age is tougher to estimate. Lead researcher Manfred Kayser, who works on forensic molecular biology at Erasmus University Medical Centre, explains that the best methods of determining age rely on testing bones or teeth, but he wanted to find a method that didn’t require skeletal remains.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

photo { Helmut Newton }

science | November 23rd, 2010 4:29 pm

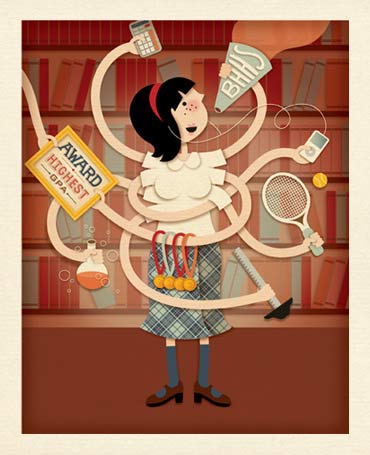

Zak gave 4 millilitres of oxytocin or a placebo saline solution to 40 male volunteers in the form of a nasal spray. The volunteers were then shown 16 commercials seeking to curtail smoking, drinking, speeding, and global warming. (…)

Significantly more people who had been given oxytocin donated money than those given saline. They also donated on average 57 per cent more money. The results were presented this week at the Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

Oxytocin is well-known for its role in empathy and trust, though is currently only available on prescription. As a result, at the moment it can’t be used by advertisers to persuade us to feel more favourable towards their product, though many make sure their adverts contain images that evoke bursts of natural oxytocin, such as children and pets, says Zak.

{ NewScientist | Continue reading }

illustration { Jessica Hische }

marketing, olfaction, scams and heists, science | November 23rd, 2010 4:27 pm

Genie was a pseudonym for a girl who was found in extremely poor conditions. Not only were her surroundings incredibly unstimulating, they were also very dirty and horrid. The author of Philo-Psych (2009) states that “After it was revealed by a doctor that Genie’s language was slightly delayed, her father considered her retarded. Presumably to shelter her from a life of shame and embarrassment, he kept her in a room, strapped to a baby toilet, and only occasionally fed her baby food for 13 years.”

Although she was 13, she had the appearance of a 7 year old, and had extremely underdeveloped linguistic skills. Rather than talking, she made noises or yelps. The case of Genie presented psychologists with various questions over social, developmental and linguistic aspects of human development.

In the following video from the BBC’s Genie: A Deprived Child, we see what the story of Genie is all about, with those who worked with her.

{ John Wayland | Continue reading | video }

illustration { Ana Bagayan }

horror, kids, psychology | November 23rd, 2010 4:07 pm

After examining studies of gender differences in such areas as cognitive abilities, communication, social behavior, personality, and psychological well-being, she concluded that for such commonly supposed gender-specific attributes as indirect aggression, leadership style, self-disclosure, moral reasoning, and delay of gratification, within-gender variability was much greater than between-gender variability. Men do throw harder, masturbate more, exhibit slightly more direct aggression, and endorse casual sex more strongly, but that’s about it.

Expectations often color objectivity, and the fact that some therapists buy into the common myths about gender differences may help explain why men often feel at a disadvantage in couples therapy, where women are supposedly so much better able to talk about feelings. Expecting less input from their male clients, therapists may miss the input when it happens, or reinforce spouses’ views that their men are biologically indifferent or incapable of being emotional.

{ Psychotherapy Networker | Continue reading }

artwork { Louise Bourgeois, Paddle Woman, 1947 | bronze }

psychology, relationships | November 22nd, 2010 8:35 pm

psychology, visual design | November 22nd, 2010 8:24 pm

Healy tells the story of the launch of bipolar disorder at the end of the 1990s. A specialised journal, Bipolar Disorder, was established, along with the International Society for Bipolar Disorders and the European Bipolar Forum; conferences were inundated with papers commissioned by the industry; a swarm of publications appeared, many of them signed by important names in the psychiatric field but actually ghost-written by PR agencies. Once the medical elites were bought and sold on the new disease, armies of industry representatives descended on clinicians, to ‘educate’ them and teach them how to recognise the symptoms of bipolar disorder.

{ London Review of Books via Phil Gyford | Continue reading }

images { 1. Picasso, Sleeping woman, gray symphony, 1943 | Gagosian Gallery, until December 23, 2010 | 2. Thomas Dworzak }

halves-pairs, health, psychology, uh oh | November 22nd, 2010 1:39 pm

Talking out our differences on controversial scientific and technological issues may be just the wrong way to reach agreement, new research suggests. (…)

The more people discussed the topic, the researchers found, the more wedded they became to their initial positions, either in support of or in opposition to the facility. The finding mirrors earlier research by Binder and some of the same co-authors around the topic of stem cell research. The more like-minded people in a homogenous group discussed the controversial science, the researchers found, the more extreme their positions became.

{ Miller-McCune | Continue reading }

psychology | November 20th, 2010 3:44 pm

Normally when I interview someone, I give them a business card and maybe the latest issue of New Scientist. Today, I give Tao a bottle of my own pee.

Chemist Tao doesn’t find this odd. Urine, he believes, could help solve the world’s energy problems, powering farms and even office buildings. And he has agreed to use my offering to show me how.

Urine might not pack the punch of rocket fuel, but what it lacks in energy density it makes up for in sheer quantity. It is one of the most abundant waste materials on Earth, with nearly seven billion people producing roughly 10 billion litres of it every day. Add animals into the mix and this quantity is multiplied several times over.

As things stand, this flood of waste poses a problem. Let it run into the water system and it would wipe out entire ecosystems; yet scrubbing it out of waste water costs money and energy. In the US, for instance, waste water treatment plants consume 1.5 per cent of all the electricity the country generates. So wouldn’t it be nice if, instead of being a vast energy consumer, urine could be put to use. (…)

To show me the process in action, Tao and Lan add my urine to the fuel cell. As it flows into the cell, a screen shows the output voltage rising to about 0.6 volts. While this prototype is too small to power a light bulb – its output is about half that of an AA battery – scaling up the cell and connecting several cells together should produce practical amounts of power.

{ NewScientist/Gizmodo | Continue reading }

artwork { Andy Warhol, Oxidation Painting, 1978 | copper metallic pigment and urine on canvas | Read: Andy Warhol’s Piss Paintings }

future, gross, science, technology | November 20th, 2010 2:44 pm

Social cognition is the scientific study of the cognitive events underlying social thought and attitudes. Currently, the field’s prevailing theoretical perspectives are the traditional schema view and embodied cognition theories. Despite important differences, these perspectives share the seemingly uncontroversial notion that people interpret and evaluate a given social stimulus using knowledge about similar stimuli. However, research in cognitive linguistics (e.g., Lakoff & Johnson, 1980) suggests that people construe the world in large part through conceptual metaphors, which enable them to understand abstract concepts using knowledge of superficially dissimilar, typically more concrete concepts.

{ Psychological Bulletin | Continue reading }

In general structure, Kant’s model of the mind was the dominant model in the empirical psychology that flowed from his work and then again, after a hiatus during which behaviourism reigned supreme (roughly 1910 to 1965), toward the end of the 20th century, especially in cognitive science.

Three ideas define the basic shape (‘cognitive architecture’) of Kant’s model and one its dominant method. They have all become part of the foundation of cognitive science.

• The mind is complex set of abilities (functions). (As Meerbote 1989 and many others have observed, Kant held a functionalist view of the mind almost 200 years before functionalism was officially articulated in the 1960s by Hilary Putnam and others.)

• The functions crucial for mental, knowledge-generating activity are spatio-temporal processing of, and application of concepts to, sensory inputs. Cognition requires concepts as well as percepts.

• These functions are forms of what Kant called synthesis. Synthesis (and the unity in consciousness required for synthesis) are central to cognition.

These three ideas are fundamental to most thinking about cognition now. Kant’s most important method, the transcendental method, is also at the heart of contemporary cognitive science.

• To study the mind, infer the conditions necessary for experience. Arguments having this structure are called transcendental arguments.

{ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy | Continue reading }

photo { John Zimmerman }

ideas, neurosciences | November 19th, 2010 10:55 am

A couple weeks ago, I wrote about a study involving mice… and circadian rhythms: too much low light (day or night) or insufficient bright light (during the day) can mess with circadian rhythms and cause bodily fatigue, jet lag, seasonal effective disorder, whatever you want to call it. It made me glad I walk to work in the bright sunshine every day and sad that my bedroom wall has big floor-to-ceiling windows.

This week, I read another study involving hamsters… and circadian rhythms: too much low light at night causes specific changes in the brain AND symptoms of depression (i don’t know how precise you can get at judging whether a hamster is depressed.)

{ Noticing/Science | Continue reading }

photo { Tom Hayes }

brain, psychology, science | November 18th, 2010 6:08 pm

Older people may have always existed throughout history, but they were rare. Aging as we know it, and the diseases and disorders that accompany it, represent new phenomena—products of 20th century resourcefulness. When infectious diseases were largely vanquished in the developed world, few anticipated the extent to which chronic degenerative diseases would rise. We call them heart disease, cancer, stroke, arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, and many more, but we might as well collectively use one word to describe them all—aging.

Aging may be defined as the accumulation of random damage to the building blocks of life—especially to DNA, certain proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids (fats)—that begins early in life and eventually exceeds the body’s self-repair capabilities. This damage gradually impairs the functioning of cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems, thereby increasing vulnerability to disease and giving rise to the characteristic manifestations of aging, such as loss of muscle and bone mass, decline in reaction time, compromised hearing and vision, and reduced elasticity of the skin. (…)

Humanity is paying a heavy price for the privilege of living extended lives—a new and much more complicated relationship with disease.

{ Slate | Continue reading }

related { Some animals live for 400 years. What can they teach us about extending life? }

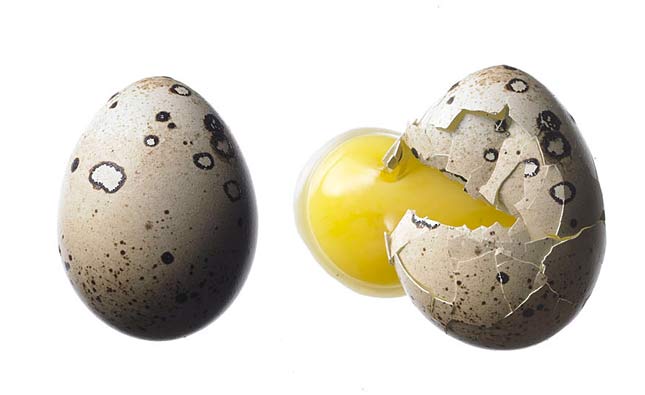

photo { Misha De Ridder }

health, ideas, science, time | November 18th, 2010 4:14 pm

What do you do when you’re stressed out?

Talk to friends? Listen to music? Have a drink, or eat some ice cream? Or maybe practice yoga? These things are all pleasant options, and they’re obvious, effective ways to deal with stress. Chances are that you would not even think about doing something like, say, cutting your arm with a knife until you draw blood. Yet inflicting pain is exactly what millions of Americans – particularly adolescents and young adults – do to themselves when they’re stressed.

This is called nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), and it most commonly takes the form of cutting or burning the skin. Traditionally, many doctors, therapists, and family members have believed that people engage in NSSI primarily to manipulate others.

However, recent research has found that such social factors only motivate a minority of cases. Although there are many reasons why people engage in this kind of self-injury, the most commonly reported reason is simple, if seemingly odd: to feel better. Several studies support the claim that self-inflicted pain can lead to feeling better.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

photo { Edward Weston }

kids, psychology | November 18th, 2010 2:45 pm

Conversations on news sites show how information and ideas spread.

There’s a science behind the comments on websites. It’s actually quite predictable how much chatter a post on Slashdot or Wikipedia will attract, according to a new study of several websites with large user bases. (…)

The findings give hope to social scientists trying to understand broader phenomena, like how rumors about a candidate spread during a campaign or how information about street protests flows out of a country with state-controlled media.

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

photo { Michael Casker }

ideas, science, social networks, technology | November 18th, 2010 2:20 pm

…areas of science, technology and medicine that are regressing. (…) I mean fields of research that actually go backward, as measured by some specific benchmark. Some examples:

* The end of infectious disease: Decades ago antibiotics, vaccines, pesticides, water chlorination and other public health measures were vanquishing diseases such as malaria, yellow fever, polio, whooping cough, tuberculosis and smallpox, particularly in First World nations. (…) Hopes for the end of infectious disease were soon crushed, however, by the emergence of AIDS, mutant flu viruses and antibiotic-resistant forms of old killers such as tuberculosis. (…)

* The origin of life: In 1953 Harold Urey of the University of Chicago and his graduate student Stanley Miller simulated the “primordial soup” in which life supposedly began on Earth some four billion years ago. They filled a flask with methane, ammonia and hydrogen (representing the primordial atmosphere) and water (the oceans) and zapped it with a spark-discharge device (lightning). The flask was soon coated with a reddish goo containing amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. This famous experiment raised the hopes of many scientists that one of nature’s deepest mysteries—genesis, the origin of life on Earth—would soon be replicated in the laboratory and hence solved. It hasn’t worked out that way. Scientists have failed to show how mere chemicals can become animate, and the origin of life now appears more improbable and mysterious than ever.

{ John Horgan/Scientific American | Continue reading }

artwork { Barnett Newman, The Promise, 1949 | Oil on canvas | Whitney Museum of American Art, New York }

health, mystery and paranormal, science, transportation, uh oh | November 17th, 2010 9:11 pm

Women are generally thought to be less willing to take risks than men, so he speculated that the banks could balance out risky men by employing more women. Stereotypes like this about women actually influence how women make financial decisions, making them more wary of risk, according to a new study published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Anecdotally, many people believe that women are more risk averse and loss averse than men—that women make safer and more cautious financial decisions. And some research has supported this, suggesting that the gender differences may be biologically rooted or evolutionarily programmed.

But Priyanka B. Carr of Stanford University and Claude M. Steele of Columbia University thought that these differences might be the result of negative stereotypes—stereotypes about women being irrational and illogical. So they designed experiments to study how women make financial decisions, when faced with negative stereotypes and when not.

{ APS | Continue reading }

psychology | November 17th, 2010 8:55 pm

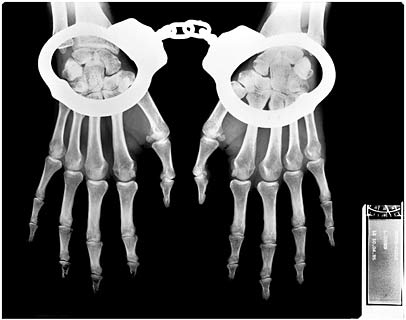

What makes people psychopaths is not an idle question. Prisons are packed with them. So, according to some, are boardrooms. The combination of a propensity for impulsive risk-taking with a lack of guilt and shame (the two main characteristics of psychopathy) may lead, according to circumstances, to a criminal career or a business one. That has provoked a debate about whether the phenomenon is an aberration, or whether natural selection favours it, at least when it is rare in a population. (…)

Despite psychopaths’ ability to give the appropriate answer when confronted with a moral problem, they are not arriving at this answer by normal psychological processes. In particular, the two researchers thought that psychopaths might not possess the instinctive grasp of social contracts—the rules that govern obligations—that other people have.

Most people understand social contracts intuitively. They do not have to reason them out.

{ The Economist | Continue reading }

illustration { Scott Hunt }

psychology, uh oh, weirdos | November 17th, 2010 8:05 pm

Why estrogen makes you smarter

Estrogen is an elixir for the brain, sharpening mental performance in humans and animals and showing promise as a treatment for disorders of the brain such as Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia. But long-term estrogen therapy, once prescribed routinely for menopausal women, now is quite controversial because of research showing it increases the risk of cancer, heart disease and stroke.

Northwestern Medicine researchers have discovered how to reap the benefits of estrogen without the risk. Using a special compound, they flipped a switch that mimics the effect of estrogen on cortical brain cells. The scientists also found how estrogen physically works in brain cells to boost mental performance, which had not been known.

When scientists flipped the switch, technically known as activating an estrogen receptor, they witnessed a dramatic increase in the number of connections between brains cells, or neurons. Those connections, called dendritic spines, are tiny bridges that enable the brain cells to talk to each other.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Thobias Faldt }

brain, science | November 17th, 2010 6:35 pm

The secret behind the beautiful songs that birds sing has been decoded and reproduced for the first time.

One of the great challenges in neuroscience is to explain how collections of neural circuits produce the complex sequences of signals that result in behaviours such as animal communication, birdsong and human speech.

Among the best studied models in this area are birds such as zebra finches. These enthusiastic singers produce songs that consist of long but relatively simple sequences of syllables. These sequences have been well studied and their statistical properties calculated.

It turns out that these statistical properties can be accurately reproduced using a type of simulation called a Markov model in which each syllable is thought of as a state of the system and whose appearance in a song depends only on the statistical properties of the previous syllable. (…)

But other birds produce more complex songs and these are harder to explain. One of these is the Bengalese finch whose songs vary in seemingly unpredictable ways and cannot be explained a simple Markov model. Just how the Bengalese finch generates its song is a mystery.

Until now. (…) Instead of the simple one-to-one mapping between syllable and circuit that explains zebra finch song, they say that in Bengalese finches there is a many-to-one mapping, meaning that a given syllable can be produced by several neural circuits. That’s why the statistics are so much more complex, they say.

This type of model is called a hidden Markov model because the things that drives the observable part of the system–the song–remains hidden.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

related { New research suggests that our brains have a built-in bias against people whose accents don’t sound like our own }

birds, music, neurosciences, science | November 17th, 2010 6:33 pm

For the first time, scientists have converted information into pure energy, experimentally verifying a thought experiment first proposed 150 years ago.

The idea was originally formulated by physicist James Clerk Maxwell, but it gained controversy because it appeared to violate the second law of thermodynamics. Put in experimental terms, this law states that when hot and cold water are mixed, they will eventually reach an equilibrium middling temperature.

Maxwell proposed that a hypothetical being (later dubbed Maxwell’s demon) could separate the water into two compartments and reverse the process, isolating hot molecules from cold by letting only the hotter-than-average through a trap-door between the compartments.

Because mixed water is considered more disordered (i.e. of higher entropy) than separated water, the demon has converted a system from a state of disorder to a state of order, using only information (the knowledge of which molecules were hot and cold).

{ LiveScience | Continue reading }

photo { Boru O’Brien O’Connell }

science, water | November 17th, 2010 6:25 pm

Despite rumors to the contrary, there’s many ways in which the human brain isn’t all that fancy. Let’s compare it to the nervous system of a fruit fly. Both are made up of cells — of course — with neurons playing particularly important roles. Now one might expect that a neuron from a human will differ dramatically from one from a fly. Maybe the human’s will have especially ornate ways of communicating with other neurons, making use of unique “neurotransmitter” messengers. Maybe compared to the lowly fly neuron, human neurons are bigger, more complex, in some way can run faster and jump higher.

But no. Look at neurons from the two species under a microscope and they look the same. They have the same electrical properties, many of the same neurotransmitters, the same protein channels that allow ions to flow in and out, as well as a remarkably high number of genes in common. Neurons are the same basic building blocks in both species.

So where’s the difference? It’s numbers — humans have roughly a million neurons for each one in a fly. And out of a human’s 100 billion neurons emerge some pretty remarkable things. With enough quantity, you generate quality.

Neuroscientists understand the structural bases of some of these qualities.

{ NY Times | Continue reading | On the Human/National Humanities Center }

brain, neurosciences | November 16th, 2010 7:05 pm