Like exude of margary!

{ Assistants at work in Takashi Murakami’s New York Studio. | Five art superstars in their studios | The Guardian | full story }

{ Assistants at work in Takashi Murakami’s New York Studio. | Five art superstars in their studios | The Guardian | full story }

The Eurasia Group, a political risk consultancy, has come out with its list of Top Risks for 2011. (…)

1 — The G-Zero:

We are entering the era of G-Zero, a world order in which no country or bloc of countries has the political and economic leverage to drive an international agenda. The US lacks the resources to continue as primary provider of public goods, and rising powers are too preoccupied with problems at home to welcome the burdens that come with international leadership. As a result, economic efficiency will be reduced and serious conflicts will arise.2 — Europe:

While the eurozone will undoubtedly remain intact in 2011, the region’s political crises will become increasingly unmanageable. There’s a real concern that core European countries (such as Germany) will become less committed to the peripherals, in turn hurting policy coordination and undermining market confidence in the EU.3 — Cybersecurity and geopolitics:

In 2011, geopolitics and cybersecurity will collide. Whether attacks are waged for power (state versus state), profit (particularly among state capitalists), or pleasure (from info-anarchists, as in the recent WikiLeaks case), this is a key development to watch. Governments, corporations, and banks are all vulnerable to sudden, radical transparency, and a debilitating attack could be a long-term game changer.

Screenshot { Disney’s Cinderella, 1950 }

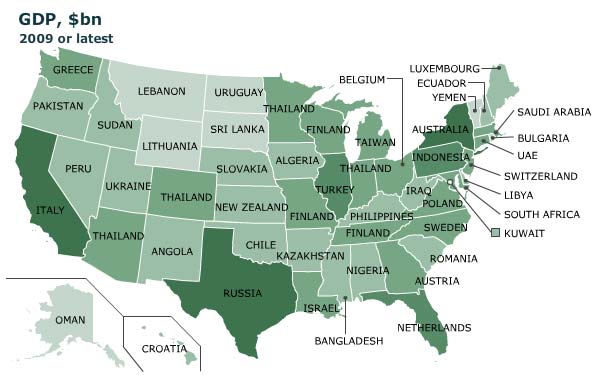

{ It has long been true that California on its own would rank as one of the biggest economies of the world. These days, it would rank eighth, falling between Italy and Brazil on a nominal exchange-rate basis. But how do other American states compare with other countries? | The Economist }

Shadow banking—the intricate web of financial arrangements and techniques that developed symbiotically with the traditional, regulated banking system over the past 30 or so years—is territory Gorton has studied for decades, but it (and he) have been largely on the periphery of mainstream economics and policy.

That all changed in mid-2007, when panic broke out in the subprime mortgage market and financial institutions that support it. Expressions like “collateralized debt obligation” and “repo haircut” escaped the confines of Wall Street and business schools, and began to fill the airwaves. We’re still struggling to come to terms—and few are in a better position to help than Gorton.

Gary Gorton: The term shadow banking has acquired a pejorative connotation, and I’m not sure that’s really deserved. So let me provide some context for banking in general.

Banking evolves, and it evolves because the economy changes. There’s innovation and growth, and shadow banking is only the latest natural development of banking. It happened over a 30-year period. It’s part of a number of other changes in the economy. And let me give even a little more context, historical context. I want to convince you that shadow banking is not a new phenomenon, in a sense—that we have had previous “shadow banking” systems in the past—and that there is an important structure to bank debt that makes it vulnerable to panic. So, the crisis is not a special, one-time event, but something that has been repeated throughout U.S. history.

Before the Civil War, banking involved issuing private money—that is, banks issued their own currency or bank notes. And this system worked in the way economists would expect it to work. The private bank money did not trade at par when it circulated any significant distance from the issuing bank. Instead, it was subject to a discount, so that a bank note issued by a New Haven bank as a $10 note might only be worth $9.50 at a store in New York City, for example.

Such discounts from par reflected the risk that the issuing bank might not have the $10—redeemable in gold or silver coins—by the time the holder took the note back to New Haven from New York. The discounts from par were established in local markets. But you can see the problem of trying to buy your lunch when the cook has to figure out the discount. It was simply hard to buy and sell things in such a world.

A big innovation in that period was to back the money by collateral, by state bonds. It turned out that this didn’t always work very well because the bonds themselves were risky. The National Banking Act then corrects this by having the government take over money and issue greenbacks, or federal government notes backed by Treasuries. That was the first time in American history that money traded at par. That was 1863.

The National Banking Acts (there were two of them) are arguably the most important legislation in the financial sector in U.S. history. But what’s interesting, and the reason I bring this up, is that as that was going on, a shadow banking sector was developing. And this shadow banking sector first really makes itself felt in the Panic of 1857 when depositors run and demand currency from their checking accounts.

So, after the Civil War, there’s no problem with currency [because greenbacks were backed by the federal government], but we have this other form of bank money: checking accounts—which appears to be shadow banking.

It develops into something very large and repeatedly has crises. In the late 19th century, academics were literally writing articles with titles like “Are Checks Money?” in top economics journals. And in 1910, the National Monetary Commission, which is the precursor to the Federal Reserve System, commissions 30-some books, one of which is about the extent to which checks are used as currency for transactions. So they’re still studying it in 1910.

Eventually, as you know, we get deposit insurance, which then makes checks safe, so to speak. (…)

In the last 30 or 40 years, there have been a number of fundamental changes in our economy. One of the most fundamental of these has been the rise of institutional investing. The amount of money under management of institutional investors has just been exponentially increasing. These include pension funds, mutual funds, large money managers. And these institutions basically have a need for a checking account, if you will. So if you’re a large institutional money manager, you may need a place to put $200 million, and you want it to earn interest and to be safe and accessible. That led to the metamorphosis of a very old security: the sale and repurchase (or “repo”) market. Like a check, repo had been around for perhaps 100 years, but it was never very large.

{ Interview with Gary Gorton | The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis | Continue reading }

Recent psychological research suggests that people from Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic societies — WEIRD, for short — not only live differently from the vast majority of the world’s population, but think differently too.

The unsettling realization for psychologists — the vast majority of whom are WEIRD themselves — is that they don’t actually know much about how the rest of the world thinks. A recent study by Joseph Henrich, Steven Heine, and Ara Norenzayan at the University of British Columbia notes that in the top international journals in six fields of psychology from 2003 to 2007, 68 percent of subjects came from the United States — and a whopping 96 percent from Western, industrialized countries. In one journal, 67 percent of American subjects and 80 percent of non-American subjects were undergraduates in psychology courses.

Does this really matter? Aren’t we all the same, after all? Not really, it turns out. WEIRDos tend to be more individualistic and more competitive than people from non-industrialized Asian and African societies. In tests measuring how groups of people work together, Westerners — and Americans in particular — are far more likely to look out for themselves. They even perceive space differently. When viewing the classic Müller-Lyer illusion (>–< vs. <-->), Americans are far more often and more easily fooled than Africans, possibly as a consequence of living in a world of concrete square angles rather than natural shapes.

Myth number one is that economics is a science. It goes back quite a way. Economists, at least since Marshall, have mistakenly sought to dignify their calling by describing it as a science, and increasingly chosen to add verisimilitude to this pretence by clothing their propositions in the language of science, that is to say, mathematics. But economics is not a science. On scientific matters we rightly expect a high degree of certainty, and are ready to leave many important decisions to properly educated experts. By contrast, economic policy is more like foreign policy than it is like science, consisting as it does in seeking a rational course of action in a world of endemic uncertainty.

{ Five Myths and a Menace | Standpoint magazine | Continue reading }

photo { Stephen Shore }

The number of financial fraud cases put before the UK’s courts reached record levels in 2010, a report suggests. (…)

KPMG also highlighted the case of a group of men who were accused of using stolen credit card details to buy their own songs on iTunes, generating almost half a million pounds in royalties.

The men targeted the Apple and Amazon sites with 20 songs which they sold through the websites.

It is thought they then stole approximately 1,500 credit cards to buy the songs, and claimed back just under £469,000 in royalties.

{ BBC | Continue reading | via Chris Charfin/prefix }

photo { Moyra Davey }

The Soviet and Japanese threats to American supremacy proved chimerical. (…) The Chinese challenge to the United States is more serious for both economic and demographic reasons. The Soviet Union collapsed because its economic system was highly inefficient, a fatal flaw that was disguised for a long time because the USSR never attempted to compete on world markets. China, by contrast, has proved its economic prowess on the global stage. Its economy has been growing at 9 to 10 percent a year, on average, for roughly three decades. It is now the world’s leading exporter and its biggest manufacturer, and it is sitting on more than $2.5 trillion of foreign reserves. Chinese goods compete all over the world. This is no Soviet-style economic basket case.

Japan, of course, also experienced many years of rapid economic growth and is still an export powerhouse. But it was never a plausible candidate to be No. 1. The Japanese population is less than half that of the United States, which means that the average Japanese person would have to be more than twice as rich as the average American before Japan’s economy surpassed America’s. That was never going to happen. By contrast, China’s population is more than four times that of the United States. The famous projection by Goldman Sachs that China’s economy will be bigger than that of the United States by 2027 was made before the 2008 economic crash. At the current pace, China could be No. 1 well before then.

photo { Christopher Schreck }

The art world told us that anything could be art, so long as an artist said it was. Almost anyone who goes through a gallery door is likely to have heard about Duchamp and his urinal. The art world is less good at explaining how certain people get to be artists and decide what art is for the rest of us. This process of selection might not make aesthetic or philosophical sense, but it works anyway. It’s about power: whoever holds it gets to officiate and decide. The “art world” is a way of conserving, controlling and assigning this precious resource.

One of the most surprising findings is that people have a natural aversion to inequality. We tend to prefer a world in which wealth is more evenly distributed, even if it means we have to get by with less.

Consider this recent experiment by a team of scientists at Caltech, published earlier this year in the journal Nature. The study began with 40 subjects blindly picking ping-pong balls from a hat. Half of the balls were labeled “rich,” while the other half were labeled “poor.” The rich subjects were immediately given $50, while the poor got nothing. Such is life: It’s rarely fair.

The subjects were then put in a brain scanner and given various monetary rewards, from $5 to $20. They were also told about a series of rewards given to a stranger. The first thing the scientists discovered is that the response of the subjects depended entirely on their starting financial position. For instance, people in the “poor” group showed much more activity in the reward areas of the brain (such as the ventral striatum) when given $20 in cash than people who started out with $50. This makes sense: If we have nothing, then every little something becomes valuable.

But then the scientists found something strange. When people in the “rich” group were told that a poor stranger was given $20, their brains showed more reward activity than when they themselves were given an equivalent amount. In other words, they got extra pleasure from the gains of someone with less.

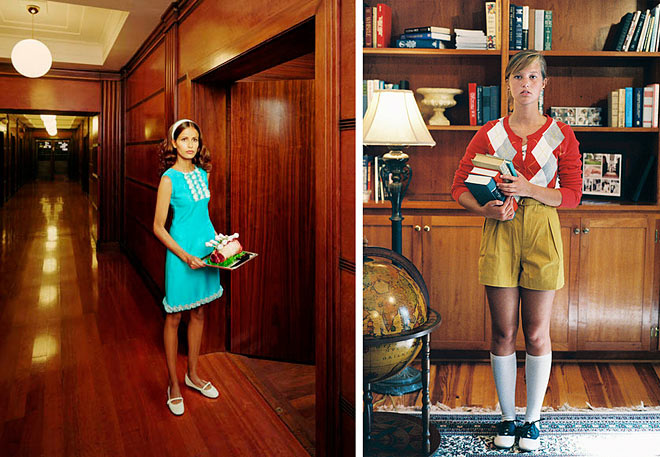

photos { David Stewart | Valerie Chiang }

Turbulence, a film by Prof. Nitzan Ben Shaul of Tel Aviv University, uses complicated video coding procedures that allow the viewer to change the course of a movie in mid-plot. In theory, that means each new theater audience can see its very own version of a film. Turbulence recently won a prize at the Berkeley Video and Film Festival for its technological innovation.

Gamers, as video-game players are known, thrill to “the pull,” that mysterious ability that good games have of making you want to play them, and keep playing them.

Miyamoto’s games are widely considered to be among the greatest. He has been called the father of modern video games. The best known, and most influential, is Super Mario Bros., which débuted a quarter of a century ago and, depending on your point of view, created an industry or resuscitated a comatose one. It spawned dozens of sequels and spinoffs. Miyamoto has designed or overseen the development of many other blockbusters, among them the Legend of Zelda series, Star Fox, and Pikmin. Their success, in both commercial and cultural terms, suggests that he has a peerless feel for the pull, that he is a master of play—of its components and poetics—in the way that Walt Disney, to whom he is often compared, was of sentiment and wonder. (…)

What he hasn’t created is a company in his own name, or a vast fortune to go along with it. He is a salaryman. Miyamoto’s business card says that he is the senior managing director and the general manager of the entertainment-analysis and -development division at Nintendo Company Ltd., the video-game giant. What it does not say is that he is Nintendo’s guiding spirit, its meal ticket, and its playful public face. Miyamoto has said that his main job at Nintendo is ningen kougaku—human engineering. He has been at the company since 1977 and has worked for no other.

{ By the time David Hurlbut bought the Harmony Club, a 20,000-square-foot building on the waterfront here, it had been abandoned for nearly 40 years. Built in 1909 as a social club by a group of prominent Jewish businessmen, it had been turned into an Elks club in the 1930s; when the Elks disbanded in 1960, the building was boarded up. | NY Times | full story }

The FBI estimates that a mid-level trafficker can make more than $500,000 dollars a year by marketing just four girls.

Youth Radio obtained a hand-written business plan from a pimp. The business plan titled Keep It Pimpin states how the pimp wants to expand his trafficking business locally as well as nationally. He also writes that he wants to discover girls “from all over”–especially girls in jail houses and in small cities.

photo { Luke Stephenson }

Usually I stay clear of connotation-rich German words that have no real equivalent in other languages. Their purpose is to obfuscate. But there is one that describes the eurozone’s crisis management rather well. It is überfordert. The nearest English translation is “overwhelmed”, or “not on top of something”, but those are not quite the same. You can be overwhelmed one day, and on top the next. Überfordert is as hopeless as Dante’s hell. It has an intellectual and an emotional component. If you are it today, you are it tomorrow.

I am not saying that every policymaker in the eurozone is hopeless. There are a few exceptions. My point is that the system is überfordert, unable to cope. This inability has several dimensions. I have identified six.

The first, and most important, is a tendency to repeat the same mistakes. The biggest of these is the repeated attempt to address solvency problems through liquidity policies. (…)The second is a lack of political co-ordination. All the decisions taken have one thing in common: no one takes political ownership of the whole system. Everybody inside the system is optimising their corner. International investors, by contrast, are looking at the system as a whole and cannot make sense of the cacophony. (…)

The third is a breakdown of communication. The EU has a tendency to hype whatever it agrees. The markets first react with euphoria to the announcement, then with disappointment once they have read the small print. When Germany raised the issue of a permanent anti-crisis mechanism, it gave few details. The markets were spooked. When news came out that Germany had climbed down over the question of automatic bondholder haircuts, the markets were euphoric. Details that have come out since are again more alarming. The way the ESM is constructed will make a debt default in the eurozone dramatically more probable. There is a good case to be made for limiting taxpayers’ liability. But the scope and the details must be conveyed much more clearly.

A fourth aspect is a tendency by governments to blame investors when something goes wrong, rather than solve the problem. (…)

Fifth is the tendency to blame each other. (…)

Finally, a sixth aspect is the tendency to appeal to a deus ex machina when all else fails. That would be the European Central Bank.

I do not want to play down the ECB’s role. Its liquidity policies prevented a calamity in August 2007, and later in the autumn of 2008. But it also delayed a resolution to the political crisis. Europe’s bank resolution policy is the ECB, and only the ECB. That is why this crisis is lasting so long.

The euro is currently on an unsustainable trajectory. The political choice is either to retreat into a corner, and hope for some miracle, or to agree a big political gesture, such as a common European bond. What I hear is that such a gesture will not happen, for a very large number of very small reasons. The system is genuinely überfordert.

Niagara Falls’ descent into blight—in spite of its proximity to an attraction that draws at least 8 million tourists each year—is a tale that Hudson’s little newspaper has been telling for years. It encompasses just about every mistake a city could make, including the one Frankie G. cited: a 1960s mayor’s decision to bulldoze his quaint downtown and replace it with a bunch of modernist follies. There was a massive hangar-like convention center designed by Philip Johnson; Cesar Pelli’s glassy indoor arboretum, the Wintergarden, which was finally torn down because it cost a fortune to heat through the Lake Erie winter; a shiny office building known locally as the “Flashcube,” formerly the headquarters of a chemical company and now home to a trinket market. Once a hydropowered center of industry, Niagara Falls is now one of America’s most infamous victims of urban decay, hollowed out by four decades of job loss, mafia infiltration, political corruption, and failed get-fixed-quick schemes. Ginger Strand, author of Inventing Niagara: Beauty, Power, and Lies, called the place “a history in miniature of wrongheaded ideas about urban renewal.”

photo { Paul Rodriguez }

For many people, the holiday season is the most wonderful time of the year. For University of Minnesota economist Joel Waldfogel, it’s the most wasteful. The problem is in the gift-giving, says Waldfogel, who highlights the fact that gifts frequently “leave recipients less than satisfied, creating what economists call a ‘deadweight loss,’” (defined as: a loss to one party that is not offset by a benefit to another). In other words, from the standpoint of economic theory, gifts are often poorly matched with the recipient’s preferences, so holiday gift-giving results in what Waldfogel calls “an orgy of value destruction.”

Did you know the Office of National Drug Control Policy has a publicly-accessible database of “street terms” for drugs? It’s like the feds’ own Urban Dictionary. But with even less accountability and oversight! (…)

Author: Doctor who writes illegal prescriptions

Boo boo bama: Marijuana

Dream gun: Opium

Gangster pills: Depressants

Oyster stew: Cocaine

Raspberry: Female who trades sex for crack or money to buy crack

Strawberry: LSD; female who trades sex for crack or money to buy crack

Toucher: User of crack who wants affection before, during, or after smoking crack

Twin towers: Heroin (after September 11)

Zoomer: Individual who sells fake crack and then fleesWhy is a bag of weed always $10 (man)?

The nominal price rigidity you describe is remarkable and unusual. If the price of weed had increased in line with US consumer price inflation, you’d be paying $20–$25 a gramme now. So I agree, it is a puzzle.

My guess is that the illegality of the market gives a push towards the price stickiness you have encountered. Buying and selling cannabis is hazardous and there must be a benefit to a situation where nobody haggles over the price.

Still, the nominal price wouldn’t stick like that unless supply and demand were at least roughly in balance at $10 a gramme. And I confess, I am perplexed. My own research, which has been purely academic, suggests that prices vary between £20 and £250 an ounce in the UK, roughly £1 to £10 a gramme. Since the price stability you describe is not matched in other markets, could it be purely fortuitous?

photo { Olivia Malone }