economics

‘The term ‘group think’ is an oxymoron.’ –G.E. Nordell

Hugh Hefner already has his final resting place picked out and paid for: a crypt next to Marilyn Monroe’s in the Westwood neighborhood of Los Angeles. Not that he has plans to use it anytime soon. Hefner, who will turn 85 in April, lives these days what appears to be the life of an invalid, or even of a cosseted mental patient: wearing pajamas all day; rarely venturing out of the house; taking most of his meals in his bedroom — the menu seldom varying, the crackers and potato chips carefully prescreened to remove any broken ones. He is hard of hearing in his right ear and has an arthritic back that causes him to lumber a little when he walks. But he is in otherwise enviable shape for an octogenarian. (…)

A couple of weeks later, Hefner was on the business pages, trying to buy back his own company. (…) Hefner startled even his own board by announcing that he wanted to make Playboy Enterprises, which he took public in 1971, private again. He offered the stockholders $5.50 a share, or more than 30 percent beyond what the stock was trading for. But this was slim consolation to investors who had been unhappily watching Hefner live like a sultan at their expense while the value of their shares declined to single digits from a high of $32.19.

Strictly speaking, Playboy Enterprises, and not Hefner, owns the Playboy Mansion, a 1920s Gothic-style spread southwest of Hollywood. Hefner pays rent and covers non-business-related expenses. The company pays for the upkeep of the house and grounds, and the salaries of the 80-employee staff, which includes a round-the-clock kitchen crew and a team of 13 who take care of Hef’s personal and business needs. Last year Hefner’s bill was $800,000, while the company kicked in $2.3 million. (…)

A late bloomer sexually, Hefner didn’t masturbate until he was 18, and after years of foreplay, he finally managed to lose his virginity when he was 22. (…)

Mr. Playboy’s heyday was the ’70s, when, as the money poured in, Hefner took to wearing pajamas round the clock, working from his bedroom, where he also slept with pretty much whomever he chose, and jetting around in the Big Bunny, his customized DC-9. The ’80s, though, were his anni horribiles. Overexpanded, the business went sour, Hefner clashed with the Reagan administration and the Moral Majority and in 1985 he suffered a stroke, in part brought on, he insisted, by the unfavorable publicity surrounding the 1980 murder of the Playmate Dorothy Stratten.

Hefner now says that his 1989 marriage to Kimberley Conrad, January Playmate of the Month the year before, was an attempt to seek refuge — a “safe harbor from the waves.” (…) He and Conrad broke up in 1998, though they did not divorce until 12 years later. “During the marriage I was faithful,” he said to me emphatically, “and she was not.” (Hefner, for all his advanced views, clings to the double standard and has never entirely got over his first wife’s admission that while they were engaged she had an affair with a high-school coach.)

‘I used to be different, now I’m the same.’ —Werner Erhard

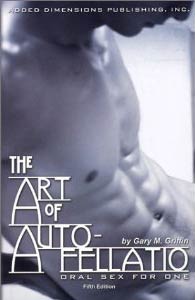

I’ve published several books, won adoring reviews, and even sold a few copies. But I’ve made almost no money and had my heart broken. Here’s everything you don’t want to know about how publishing really works.

Being the author of several critically acclaimed, moderately successful books has given me an extraordinary, exciting, occasionally lucrative, quite public life. It has also broken my heart.

Nothing makes me happier than writing. And, thanks to the rules that govern publishing today, nothing I’ve ever done for a living — housecleaning, data entry, creating campaigns for big-name, cutthroat ad agencies, full-time motherhood — has been as hard on me as being a writer.

Being an author is the culmination of a lifelong dream. And — because the sales of each book I write determine my ability to remain one — being an author has ruined many of my greatest lifelong pleasures. (…)

Believe me, I know I’m lucky to be published at all. I’ve read enough talented unpublished writers to realize just how arbitrary that privilege is. I’m more fortunate still to have had publishers who made significant investments in my books, editors who have gone to the mat for me, an agent I admire and trust. For more than a decade I’ve earned a reasonable living as a writer, raised a child as a writer, had a mostly great time being one. (…)

In the 10 years since I signed my first book contract, the publishing industry has changed in ways that are devastating — emotionally, financially, professionally, spiritually, and creatively — to midlist authors like me. You’ve read about it in your morning paper: Once-genteel “houses” gobbled up by slavering conglomerates; independent bookstores cannibalized by chain and online retailers; book sales sinking as the number of TV channels soars. What once was about literature is now about return on investment. What once was hand-sold one by one by well-read, book-loving booksellers now moves by the pallet-load at Wal-Mart and Borders — or doesn’t move at all. (…)

Book 1: Contract signed 1994. Book published 1996. Advance: $150,000.

(…)

Sales: I don’t ask. No one seems to care. Final tally: Hardcover/paperback sales combined are 10,000 copies.

Current status: Out of print. Small but loyal cult following; 10 years later adoring fans still show up at readings, clutching well-worn copies, eager to tell me how book changed their lives.

The Desperate Years: 1996-98

(…)

Agent submits new manuscript to Editor Who Still Loves Me (despite disappointing sales of first book). EWSLM, enthused, takes manuscript to pub board. Sales director rejects new book, citing losses incurred by first one. EWSLM acknowledges to agent: It’s not the book being rejected; it’s the author. (…)

Agent offers EWSLM unprecedented deal: If publisher will buy new book, we’ll forgo advance to help defray losses from first one. EWSLM gently advises agent to “pursue other avenues.” Agent gently advises me to “pursue other genres.” (…)

Question to potential new agent: “Do you think changing agents will help my career?”

New agent’s answer (in so many words): “It sure can’t hurt.”

Book 3: Contract signed 1998. Book published 2001. Advance: $10,000

Book takes two years, intensive research, mostly joy to write.

Book rejected by 10 publishers; lone editor making offer promises to “make up for the modest advance with great publicity on the back end.” Desperate to “get back in the game,” I accept advance that’s less than 10 percent of first one from editor who never returns my calls, continues to misspell my name.

Book 4: Contract signed 2002. Book published 2004. Advance: $80,000

Book takes two years, hellish research, difficult and delightful to write. (…)

Book 5

New book proposal written overnight, submitted to editor of Book 4. Editor loves idea, pitches to pub board. Pub board loves idea, agrees to make offer. Editor/agent have celebratory lunch. (…)

Three weeks after celebratory lunch, normally overly optimistic agent calls, sounding near tears. “It’s bad, Jane. They’re not going to make an offer.”

An axe for the frozen sea inside of us

It’s a gig actors call “corpse duty,” and in a shrinking market for jobs in scripted TV, dead-body roles are on the rise.

In the past few years, TV dramas have responded to feature-film trends and HDTV, which shows everything in more realistic detail, by upping the violence and delivering more shock value on the autopsy table.

The Screen Actors Guild doesn’t keep figures on corpse roles, but currently, seven of the top 10 most-watched TV dramas use corpse actors, including CBS’s “CSI,” “NCIS” and spinoff “NCIS: Los Angeles.” The new ABC series “Body of Proof” revolve1s around a brilliant neurosurgeon turned medical examiner who solves murders by analyzing cadavers.

It all means more work for extras, casting agents and makeup artists who supply corpses in various stages of decomposition.

photo { Christopher Payne, Autopsy theater of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington DC }

Any dog’s life you list you may still hear them at it, like sixes and seventies as eversure as Halley’s comet

What distinguishes great entrepreneurs? Discussions of entrepreneurial psychology typically focus on creativity, tolerance for risk, and the desire for achievement—enviable traits that, unfortunately, are not very teachable.

So Saras Sarasvathy, a professor at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business, set out to determine how expert entrepreneurs think, with the goal of transferring that knowledge to aspiring founders. (…)

Sarasvathy concluded that master entrepreneurs rely on what she calls effectual reasoning. Brilliant improvisers, the entrepreneurs don’t start out with concrete goals. Instead, they constantly assess how to use their personal strengths and whatever resources they have at hand to develop goals on the fly, while creatively reacting to contingencies.

By contrast, corporate executives—those in the study group were also enormously successful in their chosen field—use causal reasoning. They set a goal and diligently seek the best ways to achieve it.

photo { Richard Avedon }

related { Sun Tzu: The Enemy of the Bureaucratic Mind }

‘Je vidais gentiment mes testicules.’ –Michel Houellebecq

According to a recent study commissioned by the Japanese government, the country’s desire for sex is dropping quickly.

The biennial survey, originally designed to gauge the success of the country’s birth-control education, revealed that 36.1 percent of Japanese males between 16 and 19 had no interest in or even loathed sex. In 2008, that number was 17.5 percent.

Of girls in that 16–19 age group, 59 percent had no interest in sex, up 12 points from 2008.

Forty percent of married people admitted to not having sex within the last month.

Overall, the fertility rate in Japan has dropped to 1.37 births per woman. It’s 2.06 in the U.S. Such a low rate, if it continues, could have major consequences for the Japanese economy.

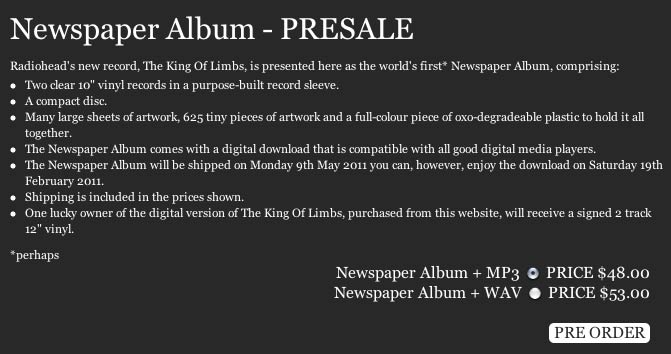

image { Amazon.com }

You see me shinin, lit up with diamonds as I stay grindin. Uh-huh.

I have only met Arianna Huffington once. I remember it vividly but my guess is she doesn’t remember it much at all, which says volumes about both of us. The scene was surreal. Huffington and I were in Larry Flynt’s office in Los Angeles, participating in an experimental online talk show Larry was trying to distribute over the Internet. Our topic for the moment was gun control: I was conflicted while Huffington was violently opposed to guns, citing their danger to children, which she thought should over-rule any constitutional argument. I made a point and she replied with the motherhood card, “Well you obviously have never had children.” Point and match for Huffington. Game over.

But I had children. Back then I was the father of two sons, one of whom had died in my arms only a few months before. That memory was still too vivid for me to even respond to Huffington, who took my silence as capitulation, and maybe it was. She easily threw her kids into the battle while I couldn’t do the same with mine.

Maybe she sensed my weakness.

That was long before the Huffington Post was even thought of, but it was the first thing that came to mind when I read this week that AOL was buying the blog for $315 million. What AOL is buying, primarily, is Arianna Huffington in her role as media baron (baroness?) in the Fleet Street tradition, and it is a perfect fit. Huffington is at heart a female Rupert Murdoch, she just came to it too late in life. Like Murdoch she is all about taking a position and relentlessly pushing it to attract like-minded readers and advertisers. The story is everything. Well that and the money.

Did I mention that, inspired by Huffington, this blog, too, is for sale? By her metrics it’s worth $20 million, but I’d take a tenth of that.

related { Barry Ritholtz | AOL-Huffington Post: Why the Heavy Breathing? }

Money isn’t everything, but it’s right up there next to oxygen

Nasa has 18 facilities across the US, from Maryland to California, and its major contractors, companies such as Boeing and Lockheed Martin, have dozens more. But no place has assumed the identity of the country’s space programme quite like Brevard County. A mosquito-bitten slip of coast, 20 miles wide and 70 miles long, it was somewhere people used to drive through on their way to Palm Beach, until the US army decided to start testing its missiles there in October 1946.

And then, quite suddenly, it was colonised. The arrival of Wernher von Braun, designer of the V2 rocket, and the other founding fathers of the US space programme, made Brevard the fastest-growing county in America. Nasa, founded in 1958, built bridges and water systems, and when the space race reached its exorbitant heights in the mid-1960s, Brevard was the edge of the world. Astronauts raced their cars on the beach, newsmen camped out on their lawns and the county was given the dialling code 3-2-1 after the launch sequence. In 1973, Brevard put the Moon landing on its county seal.

The Apollo boom was followed by bust: 10,000 people lost their jobs when the programme was cancelled in 1972. But since then, Brevard has rebuilt itself around the space shuttle, Nasa’s longest-serving spacecraft and one of the most recognisable vehicles ever to fly. The parts may be manufactured elsewhere and its missions managed from Houston, but for the past three decades Brevard County and KSC have been, in Nasa-speak, where the rubber hits the road. The tourist-friendly launches and everlasting work of 132 missions have made the shuttle the central activity of America’s Space Coast—the stuff of daily life and conversation. (…)

Brevard hasn’t escaped the property crash. Property values in Brevard County have fallen by 45 per cent since 2007 and are still falling—more than 10 per cent last year. (…) Yet it is nothing compared to what is to come, because the rockets and the recession are about to collide. There will be at least two or maybe three missions this year: Discovery, planned for February; the official final flight, Endeavour, scheduled for 1st April; and possibly a “final final” mission if Atlantis gets the go-ahead, most likely in June. But at some point in 2011, the space shuttle will fly for the last time.

photo { Brian Ulrich }

‘I am aware that these terms are employed in senses somewhat different from those usually assigned. But my purpose is to explain, not the meaning of words, but the nature of things.’ –Spinoza

The Allstate Corporation today issued the following statement:

We recently issued a press release on Zodiac signs and accident rates, which led to some confusion around whether astrological signs are part of the underwriting process.

Astrological signs have absolutely no role in how we base coverage and set rates. Rating by astrology would not be actuarially sound. We realize that our hard working customers view their insurance expense very seriously. So do we.

We deeply apologize for any confusion this may have caused.

{ PR Newswire | Continue reading | Thanks Tim }

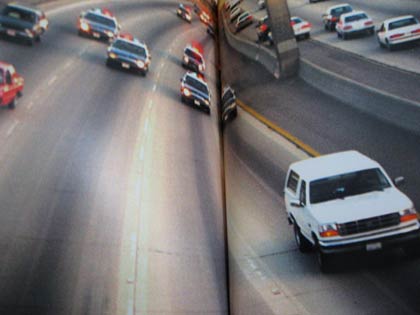

photo { Bronco Chase, Los Angeles, June 17, 1994 }

Give me a dutch and a lighter I’ll spark shit

The president was too polite to mention it during his State of the Union speech on Tuesday, but here’s a quick summary of the problem: The U.S. is broke. The hole is too big to plug with cost cutting or economic growth alone. Rich people have money. No one else does. Rich people have enough clout to block higher taxes on themselves, and they will. (…)

Whenever I feel as if I’m on a path toward certain doom, which happens every time I pay attention to the news, I like to imagine that some lonely genius will come up with a clever solution to save the world. Imagination is a wonderful thing. I don’t have much control over the big realities, such as the economy, but I’m an expert at programming my own delusions. (…)

As a public service, today I will teach you how to wrap yourself in a warm blanket of imagined solutions for the government’s fiscal dilemma.

To begin, assume that as the fiscal meltdown becomes more perilous, everyone will become more flexible and perhaps a bit more open-minded. That seems reasonable enough. A good crisis has a way of changing people. Now imagine that the world needs just one great idea to put things back on the right track. Great ideas have often changed history. It’s not hard to imagine it can happen again.

Try to imagine that the idea that saves the country is an entirely new one. (…)

Convincing the rich to accept higher taxes on themselves.

‘Satire is a lesson, parody is a game.’ –Nabokov

The really surprising number you saw the talking heads on TV mention was the growth of consumer spending, at 4.4%. Is the US consumer back? After all, real final sales rose by 7.1%, a number not seen since 1984 and Ronald Reagan. But real income rose a paltry 1.7%. Where did the money that was spent come from?

Savings dropped a rather large 0.5% for the quarter. That was part of it. And I can’t find the link, but there was an unusual drawdown of money market and investment accounts last quarter, somewhere around 1.5%, if I remember correctly. That would just about cover it. But that is not a good thing and is certainly not sustainable.

Let’s see what good friend David Rosenberg has to say about those numbers:

Even with the Q4 bounce, real final sales have managed to eke out a barely more than 2% annual gain since the recession ended, whereas what is normal at this stage of the cycle is a trend much closer to 4%. Welcome to the new normal.

There is no doubt that there will be rejoicing in Mudville because real GDP did manage to finally hit a new all-time high in Q4. The recession losses in output have been reversed (though what that means for the 7 million jobs that have to be recouped is another matter). But, before you uncork the champagne, just consider what it has taken just to get the economy back to where it was three years ago:

· The funds rate moved down from 4.5% to zero.

· The Fed’s balance sheet expanded by more than 1.5 trillion dollars.

· The printing of M2 money supply of around 1 trillion dollars (the illusion of prosperity).

· Expansion of federal government debt of 4.8 trillion dollars.

All this heavy lifting just to take the economy back to where it was in the fourth quarter of 2007.

(…)

Thursday was the annual Tiger 21 conference, and the room held about 150 or so very-high-net-worth participants. The lunch session was Greta van Sustern interviewing Newt Gingrich. And yes, from what I heard he is going to run.

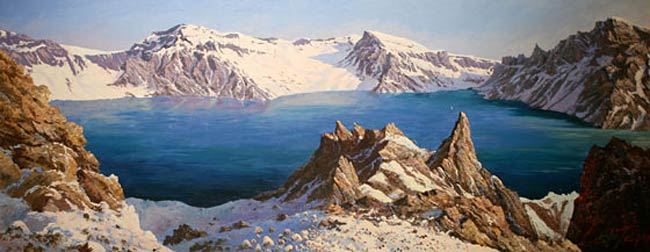

painting { Ju Myung Kim }

From coast to coast so you stop being like a comatose

A shortage of a drug used in executions in the United States has sent U.S. states scrambling to find supplies, or alternative drugs. Among the 35 states in which capital punishment is legal, some–including Arizona and California–had been sourcing a key execution drug, sodium thiopental, through a company in London–until UK government officials put a stop to its export. The only U.S. company making the drug, which sought to move its manufacturing base to Italy, has now given up producing sodium thiopental because it cannot assure Italian officials that it won’t be used for executions.

photo { Tierney Gearon }

No standards

photo { Paul Cooley }

Not a miracle in days, oh yeah

The longest-lived of camera films has just ended its 75-year history. The only laboratory that still processed Kodachrome, the first commercially available colour slide film, stopped doing so at the end of last year. Kodak progressively withdrew the film from sale between 2002 and 2009, though many photographers loved it enough to buy large stocks to keep in their freezers. Amateurs cannot develop Kodachrome, which requires a large number of carefully controlled treatments, so, with the end of laboratory processing, the film is finished.

Kodachrome is made up of layers of black and white film, each of which responds differently to coloured light, and a series of filters. Only during processing are the appropriate dyes added to each layer to produce a colour transparency. Compared to other colour films, at least up until 1990 when Fuji introduced the garish Velvia, Kodachrome had unique advantages: its colours were rich and naturalistic, its blacks did not have the greyish cast of so many colour films, it had remarkable contrast, its greys were subtle, and the lack of colour couplers between its layers (which tend to diffuse light) gave the film extraordinary sharpness.

photo { Arnaud Pyvka }

Killa tape intro

Every Monday afternoon at the Googleplex in Mountain View, Calif., more than a dozen of Google’s top executives gather in the company’s boardroom. The weekly meeting, known as Execute, was launched last summer with a specific mission: to get the near-sovereign leaders of Google’s far-flung product groups into a single room and harmonize their disparate initiatives. Google co-founder Sergey Brin runs the meeting, along with new Chief Executive Officer Larry Page and soon-to-be-former CEO Eric Schmidt. The unstated goal is to save the search giant from the ossification that can paralyze large corporations. It won’t be easy, because Google is a tech conglomerate, an assemblage of parts that sometimes work at cross-purposes. Among the most important barons at the meeting: Andy Rubin, who oversees the Android operating system for mobile phones; Salar Kamangar, who runs the video-sharing site YouTube; and Vic Gundotra, who heads up Google’s secret project to combat the social network Facebook. “We needed to get these different product leaders together to find time to talk through all the integration points,” says Page during a telephone interview with Bloomberg Businessweek minutes before a late-January Execute session. “Every time we increase the size of the company, we need to keep things going to make sure we keep our speed, pace, and passion.”

The new weekly ritual—like the surprise announcement on Jan. 20 that Page will take over from Schmidt in April—marks a significant shift in strategy at the world’s most famous Internet company. Welcome to Google 3.0. In the 1.0 era, which ran from 1996 to 2001, Page and Brin incubated the company at Stanford University and in a Menlo Park (Calif.) garage. In 2001 they ushered in the triumphant 2.0 era by hiring Schmidt, a tech industry grown-up who’d been CEO of Novell. Now comes the third phase, led by Page and dedicated to rooting out bureaucracy and rediscovering the nimble moves of youth.

Although Google recently reported that fourth-quarter profits jumped 29 percent over the previous year, its stock rose only 13.7 percent over the past 12 months, disappointing investors and lagging the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index. Google is being outpaced by rivals such as Facebook in social networking. In 2010, Facebook served up more display ads than either Google or Yahoo!—and was visited by more U.S. Internet users. And Apple is setting the pace in mobile computing, with beloved products that use a proprietary operating system that can be closed off to Google’s services if the company so chooses.

On top of all that, there are antitrust inquiries in Washington and Europe, the defection of some top Google executives for opportunities elsewhere, and perhaps the most serious rap against the company: that its loosely organized structure is growing unwieldy and counterproductive.

I guess daisies will have to do

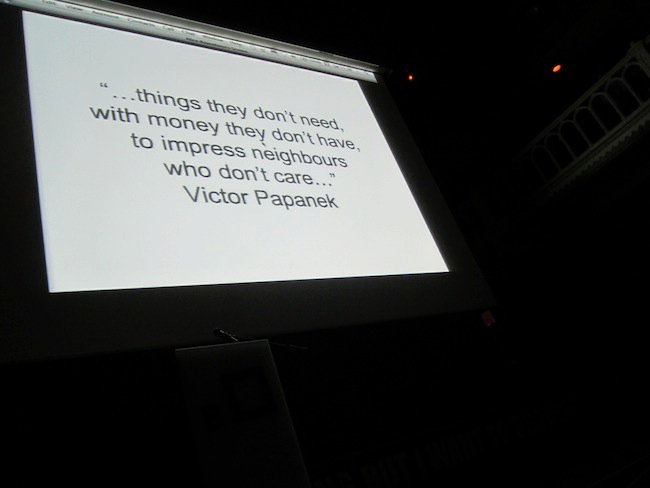

The big money isn’t in creating products, it’s in creating customers. A single, lifelong customer who lives his life spending the way you want him to is worth six or seven figures. A single one. Creating millions of these is the only way to make trillions.

You can make millions by selling a great product to people who need it, but you make billions and trillions by conditioning an entire nation of people to react to every inconvenience, every whim, and every passing desire or fear by buying something. (…)

Using the television as their primary tool, very-high-level marketers have managed to create a nation of people who typically:

▪ work almost all the time

▪ absorb several hours of advertising every night, in their own homes

▪ are tired and unhealthy and vaguely dissatisfied with their lives

▪ respond to boredom, dissatisfaction, or anxiety only by buying and consuming things

photo { Victor Cobo }

You brought me violets for my furs. And there was April in that December.

The secrets behind your flowers.

Chances are the bouquet you’re about to buy came from Colombia. (…)

To limit coca farming and expand job opportunities in Colombia, the U.S. government in 1991 suspended import duties on Colombian flowers. The results were dramatic, though disastrous for U.S. growers. In 1971, the United States produced 1.2 billion blooms of the major flowers (roses, carnations and chrysanthemums) and imported only 100 million. By 2003, the trade balance had reversed; the United States imported two billion major blooms and grew only 200 million.

photo { Alison Brady }

How about this for a wan acϟdc mercurial future

“If the old model is broken, what will work in its place?” To which the answer is: Nothing. Nothing will work. There is no general model for newspapers to replace the one the internet just broke.

With the old economics destroyed, organizational forms perfected for industrial production have to be replaced with structures optimized for digital data. It makes increasingly less sense even to talk about a publishing industry, because the core problem publishing solves — the incredible difficulty, complexity, and expense of making something available to the public — has stopped being a problem.

More plants than chants for cecilies that I was thinking

My Lux Capital partner Larry Bock and I wrote the following Trend Spotting piece highlighting the Top 9 Rise & Falls We See in the Year Ahead:

1. The Rise of Celebrity Science

Nations, cultures, economies all get what they celebrate. Celebrate celebrities and we’ll have another generation of over-consumptive, over-indebted, overweight, underemployed citizenry. But celebrate scientists: thinkers, doers, achievers, explorers, inventors, creators and we stand a shot at restoring the very human capital that led to the rise of what made our nation great. The best way to predict the future is to invent it. So I founded the largest-ever celebration of science, the USA Science & Engineering Festival, to inspire and galvanize a force of young scientists keen to invent, explore, discover and create. 1 million participants is a good start, just 299 million to go.

2. The Rise of the IPO

Nearly a decade has passed without a blockbuster set of IPOs. Hints abound that the resurgence of an IPO market is upon us. The rise of secondary markets swapping shares of Facebook and other social-networking darlings prove there is pent-up demand and that capital is ready, willing, and able to once again fund high-flying companies that didn’t exist a few years ago and are the essential companies of tomorrow. Groupon, despite having 500 competitors and being founded only two years ago may be the fastest company in history to get to a billion dollars in revenue.

3. The Rise of the Tablet

The iPad was just the start. Samsung’s Galaxy and a slate of other touch tablets will continue seizing netbook and laptop share. When we get over the buzzword and just start calling the “cloud” the “Internet” again, people will also see that the prophecies of George Gilder and Sun’s Scott McNeely—that the network is the computer—were correct all along.

4. The Rise of Nuclear & EVs

My partners at Lux Capital always tell entrepreneurs to shave with Occam’s Razor: find the simplest solution. In energy it’s nuclear power, and the electrification of everything, including cars. Watch for just-out-of-stealth startups like Kurion that are solving the problem of nuclear waste, and other breakthrough companies that will soon emerge from stealth with high-power energy conversion for electric vehicles and industrial motors. Just like the PC business in the 1980s, picking brands will be tough, but betting on the digital guts inside may make fortunes.

5. The Rise of Surprise

The most exciting things always come from unexpected upside surprises. Watch for not-widely followed areas of science and technology. Metamaterials, graphene, battery breakthroughs, solid-state lighting, augmented reality, computational photography, better energy storage and regenerative medicine are all hot areas that Lux and other VCs are on the hunt for.

6. The Fall of Super-Angels

When barriers to competition are low, expect lots of it. Hundreds of companies are getting funded by so called super angels or micro-VCs, but valuations are in the nosebleed sections. As momentum in sectors like social-networking slows (or gets saturated), some angels’ staying power could wilt as follow-on financing face tougher terms from larger VCs.

7. The Fall of Personal Privacy (& The Rise of Good Behavior?)

Regardless of what privacy advocates say: between diplomacy hackers like WikiLeaks , industrial hackers like the Stuxnet virus, geo-tagging, real-time data, status updates, tweets, check-ins, and phone cams in the hands of everyone-the facts is this: personal privacy has irreparably changed. Tech guru Kevin Kelly made a provocative statement: nobody really knows what any technology will be good for: the real question is what happens when everyone has one? Now compare modern technology as an unblinking eye with Southern gun culture. Some believe Southern gentility arose from a gun culture, where politeness was a survival tactic. If people assume they’re being watched all the time, what affect might it have on ethics and behavior?

8. The Rise of Robotics

From UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles), and military drones to autonomous systems in hospitals, factories, and shipping centers: expect robots to do the mundane, the menacing, and the miraculous.

9. The Rise of Risk

The world is more connected, less predictable and more volatile than ever before. Models widely taught in universities that assumed linear cause-and-effect, or even bell-shaped distributions in markets, are proving to contribute to more risky systems and bad decision-making. As John Maynard Keynes said, it’s better to be roughly right than precisely wrong. Low probability, high consequence events, so-called Black Swans, are on the rise with greater frequency and less predictability. Whether it’s financial crises, weather systems, or geopolitical instability-the best way to deal with risk is to know more things can happen than will and you should expect the unexpected.