Botany

Moringa oleifera, an edible tree found worldwide in the dry tropics, is increasingly being used for nutritional supplementation. Its nutrient-dense leaves are high in protein quality, leading to its widespread use by doctors, healers, nutritionists and community leaders, to treat under-nutrition and a variety of illnesses. Despite the fact that no rigorous clinical trial has tested its efficacy for treating under-nutrition, the adoption of M. oleifera continues to increase. The “Diffusion of innovations theory” describes well the evidence for growth and adoption of dietary M. oleifera leaves, and it highlights the need for a scientific consensus on the nutritional benefits. […]

The regions most burdened by under-nutrition, (in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean) all share the ability to grow and utilize an edible plant, Moringa oleifera, commonly referred to as “The Miracle Tree.” For hundreds of years, traditional healers have prescribed different parts of M. oleifera for treatment of skin diseases, respiratory illnesses, ear and dental infections, hypertension, diabetes, cancer treatment, water purification, and have promoted its use as a nutrient dense food source. The leaves of M. oleifera have been reported to be a valuable source of both macro- and micronutrients and is now found growing within tropical and subtropical regions worldwide, congruent with the geographies where its nutritional benefits are most needed.

Anecdotal evidence of benefits from M. oleifera has fueled a recent increase in adoption of and attention to its many healing benefits, specifically the high nutrient composition of the plants leaves and seeds. Trees for Life, an NGO based in the United States has promoted the nutritional benefits of Moringa around the world, and their nutritional comparison has been widely copied and is now taken on faith by many: “Gram for gram fresh leaves of M. oleifera have 4 times the vitamin A of carrots, 7 times the vitamin C of oranges, 4 times the calcium of milk, 3 times the potassium of bananas, ¾ the iron of spinach, and 2 times the protein of yogurt” (Trees for Life, 2005).

Feeding animals M. oleifera leaves results in both weight gain and improved nutritional status. However, scientifically robust trials testing its efficacy for undernourished human beings have not yet been reported. If the wealth of anecdotal evidence (not cited herein) can be supported by robust clinical evidence, countries with a high prevalence of under-nutrition might have at their fingertips, a sustainable solution to some of their nutritional challenges. […]

The “Diffusion of Innovations” theory explains the recent increase in M. oleifera adoption by various international organizations and certain constituencies within undernourished populations, in the same manner as it has been so useful in explaining the adoption of many of the innovative agricultural practices in the 1940-1960s. […] A sigmoidal curve (Figure 1), illustrates the adoption process starting with innovators (traditional healers in the case of M. oleifera), who communicate and influence early adopters, (international organizations), who then broadcast over time new information on M. oleifera adoption, in the wake of which adoption rate steadily increases.

{ Ecology of Food and Nutrition | Continue reading }

Dendrology, economics, food, drinks, restaurants, theory | September 1st, 2020 4:54 pm

Grow Your Own Cloud is a new service that helps you store your data nature’s way — in the DNA of plants.

We are at the forefront of the development of a new type of cloud, one that is organic, rather than silicon, and which emits oxygen rather than CO2.

{ GrowYourOwn.Cloud | Continue reading | Thanks Tim}

Botany, future, technology | June 13th, 2019 4:47 pm

The vast majority of life on Earth depends, either directly or indirectly, on photosynthesis for its energy. And photosynthesis depends on an enzyme called RuBisCO, which uses carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to build sugars. So, by extension, RuBisCO may be the most important catalyst on the planet.

Unfortunately, RuBisCO is, well, terrible at its job. It might not be obvious based on the plant growth around us, but the enzyme is not especially efficient at catalyzing the carbon dioxide reaction. And, worse still, it often uses oxygen instead. This produces a useless byproduct that, if allowed to build up, will eventually shut down photosynthesis entirely. It’s estimated that crops such as wheat and rice lose anywhere from 20 to 50 percent of their growth potential due to this byproduct.

While plants have evolved ways of dealing with this byproduct, they’re not especially efficient. So a group of researchers at the University of Illinois, Urbana decided to step in and engineer a better way. The result? In field tests, the engineered plants grew up to 40 percent more mass than ones that relied on the normal pathways.

{ Ars Technica | Continue reading }

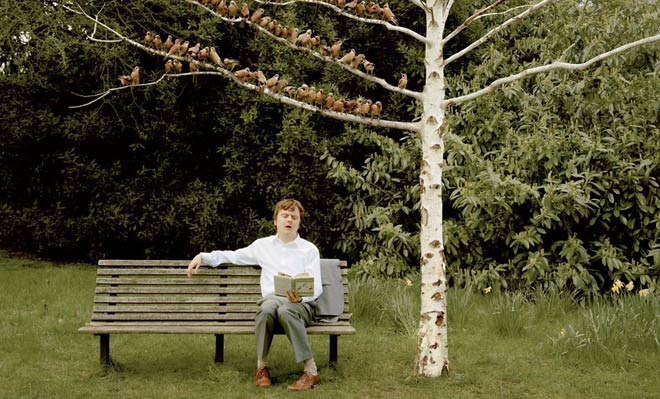

photo { Joel Meyerowitz, Florida, 1970 }

Botany, chem, photogs, science | January 11th, 2019 8:22 am

A new study published in PLoS One shows that chili seeds can perceive nearby plants even if these are enclosed in boxes. As it was not possible that the enclosed vegetables could communicate through air or soil, researchers believe that plants may be able to hear sounds.

{ United Academics | Continue reading }

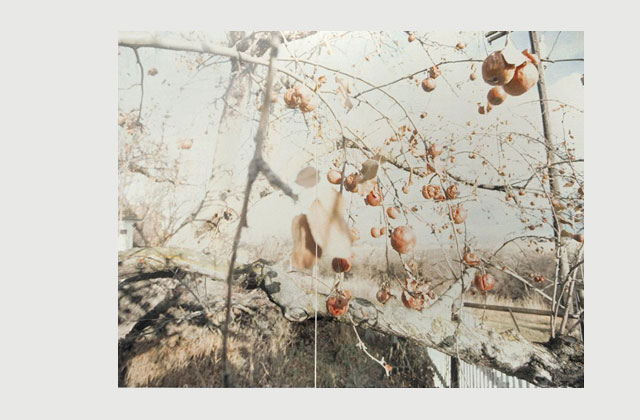

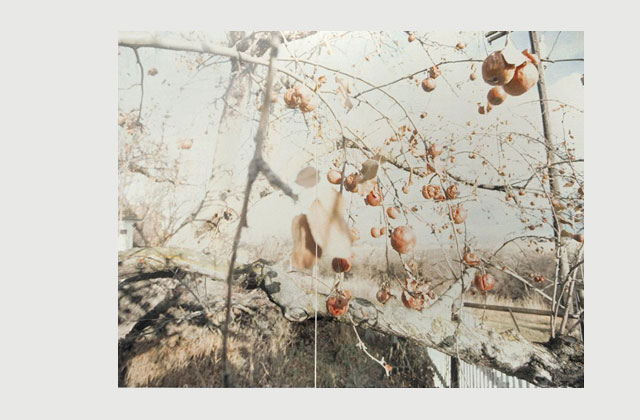

photo { Raymond Meeks }

Botany, noise and signals, science | June 11th, 2012 11:11 am

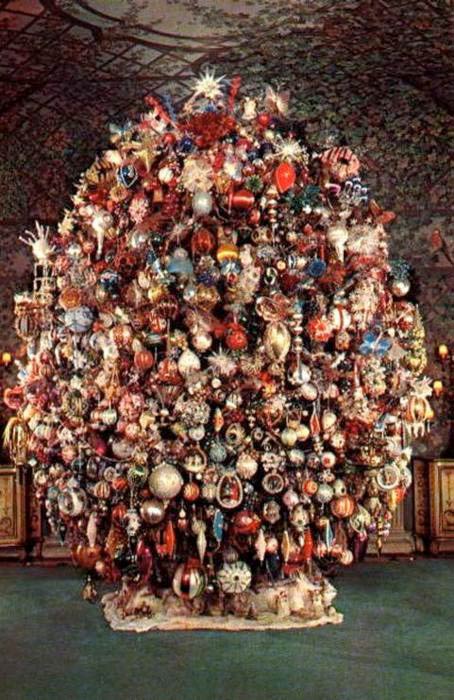

Dendrology, photogs | May 7th, 2012 11:45 am

Even after discovering and confirming a new species of plant, which is trying enough itself, botanists have to submit a description in Latin — even if they had never studied the language before — and ensure that said description is published in a journal printed on real paper.

That is until New Years Day 2012, when new rules passed at the International Botanical Congress in Melbourne, Australia this July, take effect: the botanists voted on a measure to leave the lengthy and time-consuming descriptions behind. Additionally, the group released their concerns about the impermanence of electronic publication, and will now allow official descriptions to be set in online-only journals.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

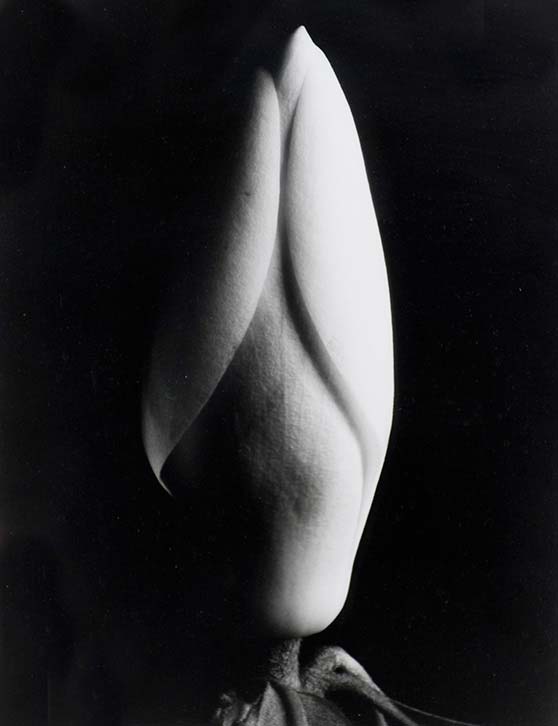

photo { Robert Mapplethorpe, Double Jack in the Pulpit, 1988 }

Botany, science | March 15th, 2012 2:16 pm

By consuming fewer calories, aging can be slowed down and the development of age-related diseases such as cancer and type 2 diabetes can be delayed. The earlier calorie intake is reduced, the greater the effect.

Researchers at the University of Gothenburg have now identified one of the enzymes that hold the key to the aging process.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

related { She was found dead that afternoon; poisoned by water. From salami to soda pop: what does “toxic” really mean?

Botany, food, drinks, restaurants, health | October 31st, 2011 2:00 pm

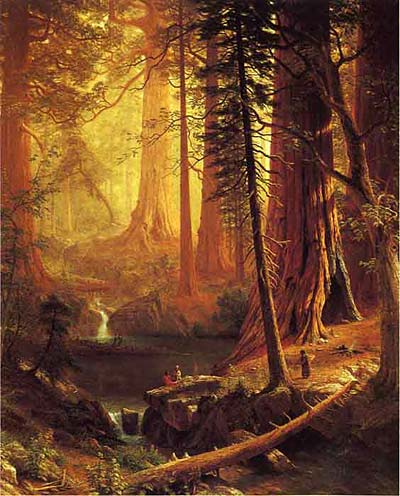

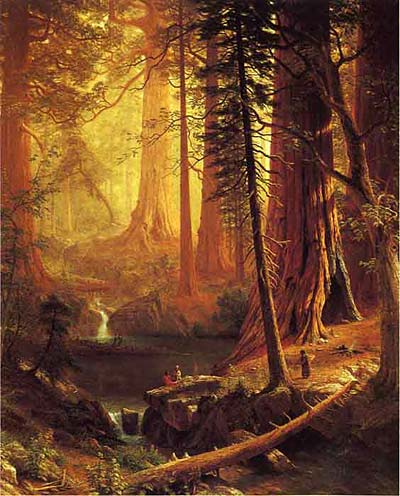

In theory, the relationship between rainfall and tree cover should be straightforward: The more rain a place has, the more trees that will grow there. But small studies have suggested that changes can occur in discrete steps. Add more rain to a grassy savanna, and it stays a savanna with the same percentage of tree cover for quite some time. Then, at some crucial amount of extra rainfall, the savanna suddenly switches to a full-fledged forest.

But no one knew whether such rapid transformations happened on a global scale. (…) Holmgren’s group identified three distinct ecosystem types: forest, savanna, and a treeless state. Forests typically had 80 percent tree cover, while savannas had 20 percent trees and the “treeless” about 5 percent or less. Intermediate states — with, say, 60 percent tree cover — are extremely rare, Holmgren says. Which category a particular landscape fell into depended heavily on rainfall.

Fire may be another important factor in determining tree cover.

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

painting { Albert Bierstadt, Giant Redwood Trees of California, 1874 }

Dendrology, science | October 17th, 2011 1:25 pm

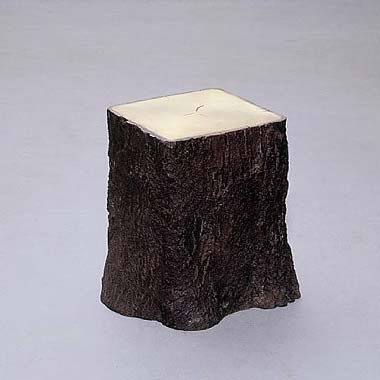

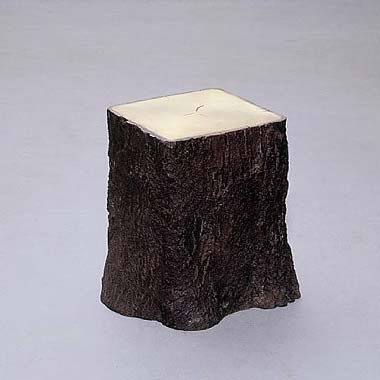

The genius behind the square tree was Robert Falls, who in the late 1980s was a PhD candidate in the U. of B.C. botany department. Falls noticed that some tree trunks exposed to high winds had become less round in cross section — they’d grown thicker on their leeward and windward sides to buttress themselves. Falls theorized that flexing of the bark by the wind encouraged the cambium— the layer of growth cells just beneath the bark — to produce extra wood. To test his theory, Falls subjected trees to what he thought might be comparable stress by scarring them with surgical tools. Sure enough, more wood grew at the site of the scars.

Hearing the news, a professor in the university’s wood science department suggested Falls try using this discovery to grow trees with a square cross section. Square trees would be a boon to the lumber industry. Since boards are flat and trees are round, only 55 to 60 percent of the average log can be sawed into lumber — the rest winds up getting turned into paper pulp and the like, or just gets thrown away. So Falls obligingly scarred seedlings of several species (western redcedar, black cottonwood, and redwood) at 90-degree intervals around their trunks. The trees responded as hoped, becoming “unmistakably squarish,” he tells me. (…)

Square trees were just the start. In 1989 Falls was awarded a Canadian patent for an “Expanded Wood Growing Process,” a bland title that fails to capture the revolutionary nature of the concept. Square trees by comparison are a mere novelty. The young scientist had come up with a way to grow boards.

{ The Straight Dope | Continue reading }

image { Bo Young Jung & Emmanuel Wolfs, Square Tree Trunk stool II, 2009 | bronze }

Dendrology, economics | October 14th, 2011 1:06 pm

When scientists delve into studies of the co-evolution of plants and their pollinators, they have something of a chicken/egg problem—which evolved first, the plant or its pollinator? Orchids and orchid bees are a classic example of this relationship. The flowers depend on the bees to pollinate them so they can reproduce and, in return, the bees get fragrance compounds they use during courtship displays (rather like cologne to attract the lady bees). And researchers had thought that they co-evolved, each species changing a bit, back and forth, over time.

But a new study in Science has found that the relationship isn’t as equal as had been thought. The biologists reconstructed the complex evolutionary history of the plants and their pollinators, figuring out which bees pollinated which orchid species and analyzing the compounds collected by the bees. It seems that the orchids need the bees more than the bees need the flowers—the compounds produced by the orchids are only about 10 percent of the compounds collected by the bees. The bees collect far more of their “cologne” from other sources, such as tree resin, fungi and leaves.

{ Smithsonian Magazine | Continue reading }

sculpture { Edgar Orlaineta }

Botany, bees | October 14th, 2011 12:00 pm

I’m going to tell you a little story about a menstruating nurse.

Dr. Bela Schick, a doctor in the 1920s, was a very popular doctor and received flowers from his patients all the time. One day he received one of his usual bouquets from a patient. The way the story goes, he asked one of his nurses to put the bouquet in some water. The nurse politely declined. Dr. Schick asked the nurse again, and again she refused to handle the flowers. When Dr. Schick questioned his nurse why she would not put the flowers in water, she explained that she had her period. When he asked why that mattered, she confessed that when she menstruated, she made flowers wilt at her touch.

Dr. Schick decided to run a test. Gently place flowers in water on the one hand… and have a menstruating woman roughly handle another bunch in order to really get her dirty hands on them.

The flowers that were not handled thrived, while the flowers that were handled by a menstruating woman wilted.

This was the beginning of the study of the menstrual toxin, or menotoxin, a substance secreted in the sweat of menstruating women.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

photo { Andres Marroquin Winkelmann }

Botany, blood, science | September 10th, 2011 7:32 pm

{ Sandro Botticelli, Primavera, ca. 1482 | Enlarge/Zoom | There are 500 identified plant species depicted in the painting, with about 190 different flowers. Of the 190 different species of flowers depicted, at least 130 have been specifically named. | Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Botany, art | April 9th, 2011 9:42 am

Dendrology, visual design | March 27th, 2011 5:00 pm

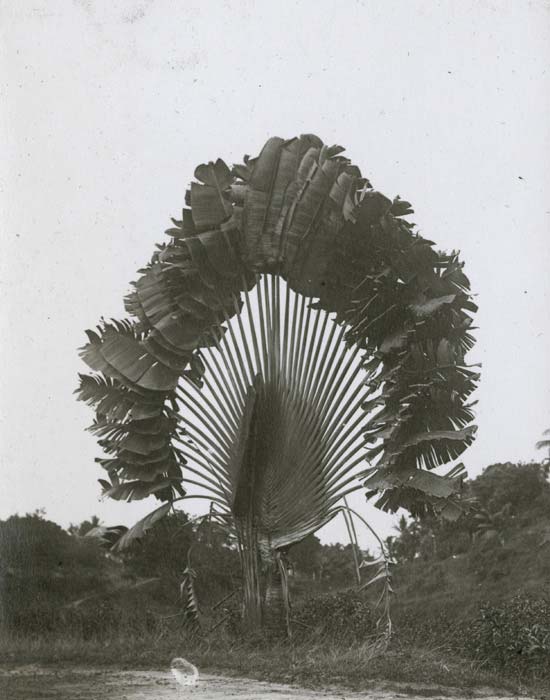

Dendrology, photogs | February 21st, 2011 10:25 am

Ask any second grader what you can do with the rings on a tree, and they’ll respond, “Learn the age of the tree.” They’re not wrong, but dendrochronology—the dating of trees based on patterns in their rings—is more than just counting rings. The hundred year-old discipline has given scientists access to extraordinarily detailed records of climate and environmental conditions hundreds, even thousands of years ago.

The ancient Greeks were the first people known to realize the link between a tree’s rings and its age but, for most of history, that was the limit of our knowledge. It wasn’t until 1901 that an astronomer at Arizona’s Lowell Observatory was hit with a very terrestrial idea—that climatic variations affected the size of a tree’s rings. The idea would change the way scientists study the climate, providing them with over 10,000 years of continuous data that is an important part of modern climate models. (…)

Dendrochronology operates under three major principles and a handful of other ground rules. The uniformitarian principle is perhaps the most important. It implies that the climate operates today in much the same way it did in the past. The uniformitarian principle does not imply that the climate today is the same as it was in the past, or even that today’s climatic conditions ever occurred in the past. It simply states that the basic processes and limiting factors are consistent through time.

{ Ars Technica | Continue reading | Dendrochronology | Wikipedia }

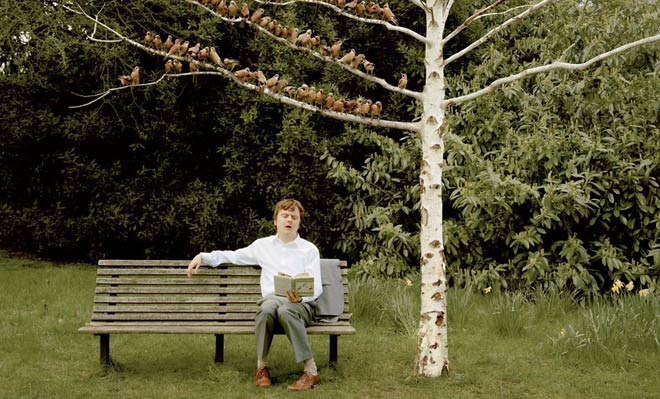

photo { David Stewart }

Botany, Dendrology, science | January 31st, 2011 8:59 am

The secrets behind your flowers.

Chances are the bouquet you’re about to buy came from Colombia. (…)

To limit coca farming and expand job opportunities in Colombia, the U.S. government in 1991 suspended import duties on Colombian flowers. The results were dramatic, though disastrous for U.S. growers. In 1971, the United States produced 1.2 billion blooms of the major flowers (roses, carnations and chrysanthemums) and imported only 100 million. By 2003, the trade balance had reversed; the United States imported two billion major blooms and grew only 200 million.

{ Smithsonian magazine | Continue reading }

photo { Alison Brady }

Botany, economics | January 26th, 2011 10:08 am

{ Will initials carved on the side of a tree always remain at the same height? Yup. | The Straight Dope | Continue reading }

Botany | December 13th, 2010 7:42 pm

Consider the orange. Citrus sinensis. Its fleshy, segmented fruit has a tight-fitting skin and contains at least 300 different chemicals. It is not easy to grow. It takes about 13 gallons of water. The fruit only ripens on the tree before it’s picked. And since they’re only grown in six states, oranges are either packed and shipped to places where citrus doesn’t grow or processed into one of America’s favorite breakfast drinks: orange juice. (…)

Lahousse charted the 10 key components of an orange in a sunburst diagram. Each color stands for a key flavor component and using the right combination of other ingredients, one could create the taste of an orange without actually using an orange.

{ Good magazine | Continue reading }

artwork { Mark Rothko, Orange and Yellow, 1956 }

Botany, food, drinks, restaurants, science | September 27th, 2010 5:39 pm

Botany, photogs | September 18th, 2010 8:44 am

Botany, photogs | August 10th, 2010 5:05 pm