ideas

If you ask a person when “middle age” begins, the answer, not surprisingly, depends on the age of that respondent. American college-aged students are convinced that one fits soundly into the middle-age category at 35. For respondents who are actually 35, middle age is half a decade away, with 40 representing the inaugural year. (…) Recently, a large sample of Swiss participants spanning several generations agreed with one another that middle-aged people are those who are between 35 to 53 years of age.

However, the precise chronological point at which we formally enter “middle age” is of little importance. (…) We’ve all heard of the dreaded “midlife crisis,” but what, exactly, is it? Furthermore, does it even exist as a scientifically valid concept? (…)

“Midlife crisis” was coined by Elliott Jacques in 1965. (…) According to him, the midlife crisis is such a crisis that many great artists and thinkers don’t even survive it. (…) He decided to crunch the numbers with a “random sample” of 310 such geniuses and, indeed, he discovered that a considerable number of these formidable talents—including Mozart, Raphael, Chopin, Rimbaud, Purcell, and Baudelaire—succumbed to some kind of tragic fate or another and drew their last breaths between the ages of 35 and 39. “The closer one keeps to genius in the sample,” Jacques observes, “the more striking and clear-cut is this spiking of the death rate in midlife.” (…)

Basically, argues Jacques, around the age of 35, genius can go in one of three directions. If you’re like that last batch of folks, you either die, literally, or else you perish metaphorically, having exhausted your potential early on in a sort of frenzied, magnificent chaos, unable to create anything approximating your former genius. The second type of individual, however, actually requires the anxieties of middle age—specifically, the acute awareness that one’s life is, at least, already half over—to reach their full creative potential. (…) Finally, the third type of creative genius is prolific and accomplished even in their earlier years, but their aesthetic or style changes dramatically at middle age, usually for the better. (…)

The phrase “midlife crisis” didn’t really creep into suburban vernacular as a catchall diagnosis until the late 1970s. This is when Yale’s Daniel Levinson, building on the stage theory tradition of lifespan developmentalist Erik Erikson, began popularizing tales of middle-class, middle-aged men who were struggling with transitioning to a time where “one is no longer young and yet not quite old.”

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

Linguistics, psychology, time | October 14th, 2011 12:12 pm

I know you’ve thought (and taught) about the fragment as a mode of writing. I’m wondering how your study of the form influences the way you use it.

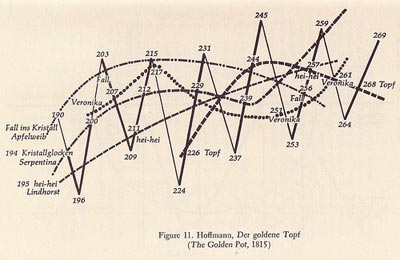

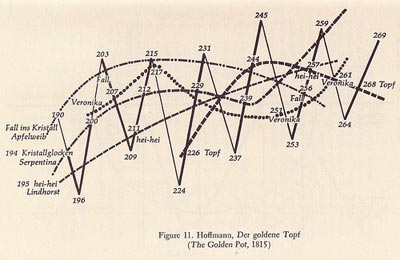

While writing a book, I’m influenced by things the same way I would imagine most writers are: I look for what I want to steal, then I steal it, and make my own weird stew of the goods. Often while writing I’d re-read the books by Barthes written in fragments—A Lover’s Discourse, Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes—and see what he gained from an alphabetical, somewhat random organization, and what he couldn’t do that way. I mostly read Wittgenstein, and watched how he used numbered sections to think sequentially, and to jump, in turn. (…) I re-read Haneke’s Sorrow Beyond Dreams, which finally dissolves into fragments, after a fairly strong chronological narrative has taken him so far.

{ Maggie Nelson/Continent. | Continue reading }

books | October 13th, 2011 5:55 am

While the Depravity Scale allows a ranking of just how depraved/horrific/ egregious specific behaviors are, the GASP scale allows us to assess the level to which others (or ourselves) are prone to guilt and shame reactions.

There are, perhaps not surprisingly, disagreements among researchers about how to distinguish between guilt and shame. According to some, guilt is largely focused on your behavior (“I did a bad thing”) while shame is focused on your character (“I am a bad person”). Others think that private (that is, not publicly known) bad behaviors cause guilt, where transgressions that are made public cause shame.

{ Keen Trial | Continue reading }

photo { Christopher Payne }

psychology, taxonomy | October 12th, 2011 2:46 pm

According to Maslow we have five needs [diagram]. However, many other people have thought about what human beings need to be happy and fulfilled, what we strive for and what motivates us, they have come up with some different numbers. (…)

David McClelland (1985) proposed that, rather than being born with them, we acquire needs over time. They may vary considerably according to the different experiences we have, but most of them tend to fall into three main categories. Each of these categories is associated with appropriate approach and avoidance behaviours.

Achievement. People who are primarily driven by this need seek to excel and to gain recognition for their success. They will try to avoid situations where they cannot see a chance to gain or where there is a strong possibility of failure.

Affiliation. People primarily driven by this need are drawn towards the achievement of harmonious relationships with other people and will seek approval. They will try to avoid confrontation or standing out from the crowd.

Power. People driven by this need are drawn towards control of other people (either for selfish or selfless reasons) and seek compliance. They will try to avoid situations where they are powerless or dependent. (…)

Martin Ford and C.W. Nichols seem to have gone a bit overboard. Their taxonomy of human goals has two dozen separate factors.

{ Careers in theory | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology, taxonomy, theory | October 12th, 2011 2:15 pm

When tracked against the admittedly lofty hopes of the 1950s and 1960s, technological progress has fallen short in many domains. Consider the most literal instance of non-acceleration: We are no longer moving faster. The centuries-long acceleration of travel speeds — from ever-faster sailing ships in the 16th through 18th centuries, to the advent of ever-faster railroads in the 19th century, and ever-faster cars and airplanes in the 20th century — reversed with the decommissioning of the Concorde in 2003, to say nothing of the nightmarish delays caused by strikingly low-tech post-9/11 airport-security systems. Today’s advocates of space jets, lunar vacations, and the manned exploration of the solar system appear to hail from another planet. A faded 1964 Popular Science cover story — “Who’ll Fly You at 2,000 m.p.h.?” — barely recalls the dreams of a bygone age.

The official explanation for the slowdown in travel centers on the high cost of fuel, which points to the much larger failure in energy innovation. (…)

By default, computers have become the single great hope for the technological future. The speedup in information technology contrasts dramatically with the slowdown everywhere else. Moore’s Law, which predicted a doubling of the number of transistors that can be packed onto a computer chip every 18 to 24 months, has remained broadly true for much longer than anyone (including Moore) would have imagined back in 1965. We have moved without rest from mainframes to home computers to the Internet. Cellphones in 2011 contain more computing power than the entire Apollo space program in 1969.

{ National Review | Continue reading }

future, ideas, technology | October 11th, 2011 12:21 pm

The “Big Five” factors of personality are five broad domains or dimensions of personality which are used to describe human personality. (…)

Openness to experience – (inventive/curious vs. consistent/cautious). Appreciation for art, emotion, adventure, unusual ideas, curiosity, and variety of experience.

Conscientiousness – (efficient/organized vs. easy-going/careless). A tendency to show self-discipline, act dutifully, and aim for achievement; planned rather than spontaneous behaviour.

Extraversion – (outgoing/energetic vs. solitary/reserved). Energy, positive emotions, surgency, and the tendency to seek stimulation in the company of others.

Agreeableness – (friendly/compassionate vs. cold/unkind). A tendency to be compassionate and cooperative rather than suspicious and antagonistic towards others.

Neuroticism – (sensitive/nervous vs. secure/confident). A tendency to experience unpleasant emotions easily, such as anger, anxiety, depression, or vulnerability.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

related { The Psychology of Unusual Handshakes. }

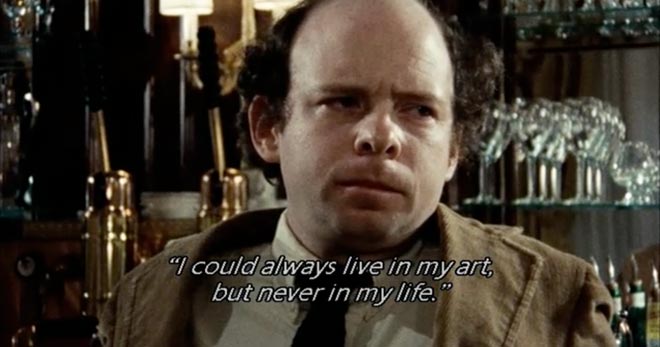

screenshot { Wallace Shawn quoting Ingmar Bergman in Louis Malle’s My Dinner with Andre, 1981 }

psychology, taxonomy | October 11th, 2011 8:30 am

There are only seven plots in all of fiction — in all of human life, really — and chances are you’re living one of them.

Plenty of people have tried to boil things down for ease of interpretation or just to get their screenplay moving. Dr. Johnson was the first to suggest “how small a quantity of real fiction there is in the world; and that the same images have served all the authors who have ever written,” but he wandered off for an ale and left the idea where it lay. (…)

In 2004 journalist Christopher Booker put it in a doorstopper of a book, The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories, and made an awfully good case that writers are all fiddling with a mere handful of stories, like songwriters with a few tunes in their pocket.

Overcoming the Monster: The Monster is your boss, mother, ex-spouse, the little voice in your head… (…)

Rags to Riches: This plot inhabits our dreams. All reality shows are rags-to-riches tryouts, as are romance novels and junior hockey games. (…)

The Quest: People go on trips, like Homer in The Odyssey and guys in road-trip movies like The Hangover. (…)

Voyage and Return: This plot sends hapless innocents into a strange landscape where they have to cope with oddity, danger and separation from all they know and love. (…)

Comedy: This is the oldest plot of all (see Aristophanes in 425 BC), based on confusion, misunderstanding and lack of self-knowledge. (…)

Tragedy: This is the most complicated plot of all.

{ Toronto Star | Continue reading }

The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations is a descriptive list which was created by Georges Polti, a French writer from the mid-19th century, to categorize every dramatic situation that might occur in a story or performance.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

ideas | October 11th, 2011 8:26 am

I predict that if we were to poll professional economists a century from now about who is the intellectual founder of the discipline, I say we’d get a majority responding by naming Charles Darwin, not Adam Smith. Smith, of course, would be the name out of 99% of economists if you asked the same question today. My claim behind that prediction is that in time, not next year, we’ll recognize that Darwin’s vision of the competitive process was just a lot more accurate and descriptive than Smith’s was. I say Smith’s–I really mean Smith’s modern disciples. Neoclassical economists. I think Smith was amazed that when you turn selfish people loose and let them seek their own interests, you often get good results for society as a whole from that process. I don’t think anybody had quite captured the logic of that narrative anywhere near as clearly as Smith had before he wrote. So, it’s a hugely important contribution. Smith, however, didn’t say you always got good results. He was quite circumspect about the claim. (…)

You go back and read Smith–it’s amazing his insights all across the spectrum have held up. Where I think he missed, or at any rate his modern disciples have missed a key feature of competition was–he saw clearly in a way that I don’t think others do yet, that competition favors individual actors. That’s what it does. Correct. Sometimes in the process it helps the larger group, but there are lots and lots of instances in which competition acts against the interests of the larger group. (…)

Familiar example from the Darwinian domain is the kinds of traits that have evolved to help individual animals do battle with one another for resources that are important. Think about polygynous mating species, the vertebrates; for the most part the males take more than one mate if they can. Obviously the qualifier is important; if some get more than one mate, you’ve got others left with none; and that’s the ultimate loser position in the Darwinian scheme. You don’t pass your stuff along into the next generation. So, of course the males fight with each other. If who wins the fights gets the mates, then mutations will be favored that help you win fights. So, male body mass starts to grow. Not without limit, but well beyond the point that would be optimal for males as a group.

{ Robert Frank/EconTalk | Continue reading }

economics, ideas | September 25th, 2011 7:55 pm

The bonds that unite another person to ourself exist only in our mind. Memory as it grows fainter relaxes them, and notwithstanding the illusion by which we would fain be cheated and with which, out of love, friendship, politeness, deference, duty, we cheat other people, we exist alone. Man is the creature that cannot emerge from himself, that knows his fellows only in himself; when he asserts the contrary, he is lying.

{ Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time, The Sweet Cheat Gone, 1925 }

artwork { Hamish Blakely }

Proust, ideas, relationships | September 25th, 2011 7:54 pm

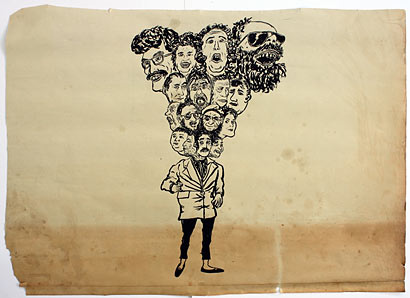

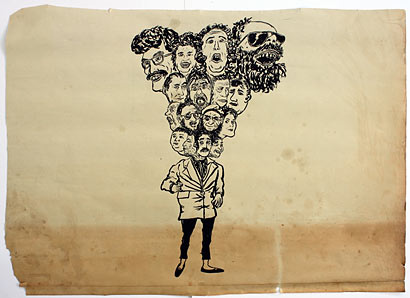

With the growing permeation of online social networks in our everyday life, scholars have become interested in the study of novel forms of identity construction, performance, spectatorship and self-presentation onto the networked medium. This body of research builds upon a rich theoretical tradition on identity constructivism, performance and (re)presentation of self. With this article we attempt to integrate the work of Italian playwright Luigi Pirandello into this tradition.

Pirandello’s classic 1925 novel Uno, Nessuno, Centomila (“One, No One and One Hundred Thousand”) recounts the tragedy of a man who struggles to reclaim a coherent identity for himself in the face of an inherently social and multi-faceted world. Via an innocuous observation of his wife, the protagonist of the novel, Vitangelo Moscarda, discovers that his friends’ perceptions of his character are not at all what he imagined and stand in glaring contrast to his private self-understanding. In order to upset their assumptions, and to salvage some sort of stable identity, he embarks upon a series of carefully crafted social experiments.

Though the novel’s story transpires in a pre-digital age, the volatile play of identity that ultimately destabilizes Moscarda has only increased since the advent of online social networks. The constant flux of communication in the online world frustrates almost any effort at constructing and defending unitary identity projections. Popular social networking sites, such as Facebook and MySpace, offer freely accessible and often jarring forums in which widely heterogeneous aspects of one’s life—that in Moscarda’s era could have been scrupu- lously kept apart—precariously intermingle. Disturbances to our sense of a unified identity have become a matter of everyday life.

Pirandello’s prescient novel offered readers in its day the contours of an identity melee that would unfurl on the online arena some 80 years later.

{ Alberto Pepe, Spencer Wolff & Karen Van Godtsenhoven, Re-imagining the Pirandellian Identity Dilemma in the Era of Online Social Networks | PDF }

books, ideas, psychology, relationships, social networks | September 24th, 2011 7:39 pm

In publishing and graphic design, lorem ipsum is placeholder text (filler text) commonly used to demonstrate the graphics elements of a document or visual presentation, such as font, typography, and layout. The lorem ipsum text is typically a section of a Latin text by Cicero with words altered, added and removed that make it nonsensical in meaning and not proper Latin. A close English translation of the words lorem ipsum might be “pain itself” (dolorem = pain, grief, misery, suffering; ipsum = itself).

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Lorem Ipsum has been the industry’s standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book. It has survived not only five centuries, but also the leap into electronic typesetting, remaining essentially unchanged. It was popularized in the 1960s with the release of Letraset sheets containing Lorem Ipsum passages, and more recently with desktop publishing software like Aldus PageMaker including versions of Lorem Ipsum.

Lorem Ipsum has roots in a piece of classical Latin literature from 45 BC, making it over 2000 years old. Richard McClintock, a Latin professor at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia, looked up one of the more obscure Latin words, consectetur, from a Lorem Ipsum passage, and going through the cites of the word in classical literature, discovered the undoubtable source. Lorem Ipsum comes from sections 1.10.32 and 1.10.33 of “de Finibus Bonorum et Malorum” (The Extremes of Good and Evil) by Cicero, written in 45 BC. This book is a treatise on the theory of ethics, very popular during the Renaissance.

The standard Lorem Ipsum passage, used since the 1500s:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

The original version:

Sed ut perspiciatis, unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam eaque ipsa, quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt, explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem, quia voluptas sit, aspernatur aut odit aut fugit, sed quia consequuntur magni dolores eos, qui ratione voluptatem sequi nesciunt, neque porro quisquam est, qui dolorem ipsum, quia dolor sit amet, consectetur, adipisci velit, sed quia non numquam eius modi tempora incidunt, ut labore et dolore magnam aliquam quaerat voluptatem. Ut enim ad minima veniam, quis nostrum exercitationem ullam corporis suscipit laboriosam, nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequatur? Quis autem vel eum iure reprehenderit, qui in ea voluptate velit esse, quam nihil molestiae consequatur, vel illum, qui dolorem eum fugiat, quo voluptas nulla pariatur?

At vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus, qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti, quos dolores et quas molestias excepturi sint, obcaecati cupiditate non provident, similique sunt in culpa, qui officia deserunt mollitia animi, id est laborum et dolorum fuga.

1914 translation by H. Rackham:

But I must explain to you how all this mistaken idea of denouncing pleasure and praising pain was born and I will give you a complete account of the system, and expound the actual teachings of the great explorer of the truth, the master-builder of human happiness. No one rejects, dislikes, or avoids pleasure itself, because it is pleasure, but because those who do not know how to pursue pleasure rationally encounter consequences that are extremely painful. Nor again is there anyone who loves or pursues or desires to obtain pain of itself, because it is pain, but occasionally circumstances occur in which toil and pain can procure him some great pleasure. To take a trivial example, which of us ever undertakes laborious physical exercise, except to obtain some advantage from it? But who has any right to find fault with a man who chooses to enjoy a pleasure that has no annoying consequences, or one who avoids a pain that produces no resultant pleasure?

On the other hand, we denounce with righteous indignation and dislike men who are so beguiled and demoralized by the charms of pleasure of the moment, so blinded by desire, that they cannot foresee the pain and trouble that are bound to ensue; and equal blame belongs to those who fail in their duty through weakness of will, which is the same as saying through shrinking from toil and pain.

{ Lipsum | Continue reading }

Linguistics, flashback | September 24th, 2011 3:20 pm

Whenever we get a day like today — down more than 500 points on the Dow at one point — my phone begins ringing with inquiries from various media.

They always ask the same question: What should investors be doing NOW?

That is the wrong question. The proper one is: What should investors have done in the past to prepare for an event like TODAY?

The bottom line remains that investing is a proactive — not reactive — endeavor. If you respond to every twitch, every news story, each turn of the wheel, you will become whipsawed.

That is no way to invest. And its no way to live life, stressing out over things that are out of your control.

What you can do is anticipate events that are cyclical in nature. These major shudders repeat every few years, so we should not be surprised by them. Construct a plan that allows you to ride out these events without panic or forced errors. You need a plan that anticipates these regular occurrences.

{ Barry Ritholtz | Continue reading }

economics, ideas, traders | September 22nd, 2011 8:26 pm

ideas | September 21st, 2011 5:53 pm

ideas, photogs, technology | September 21st, 2011 5:52 pm

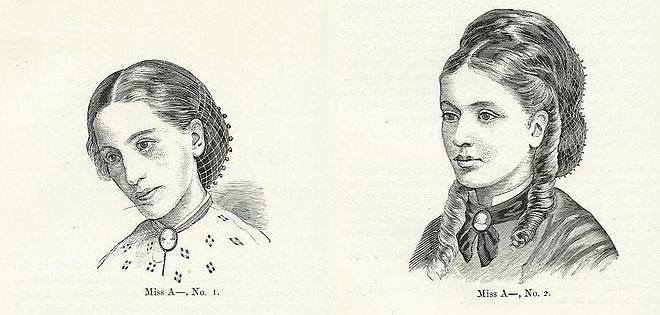

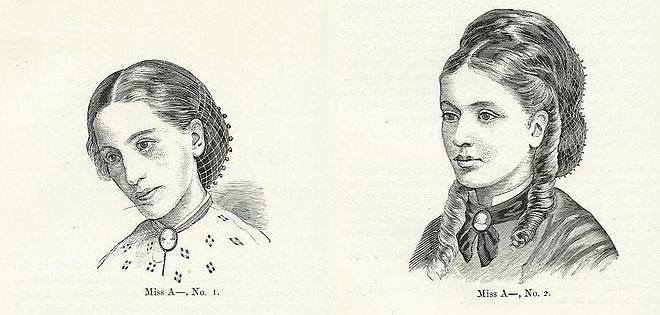

{ “Miss A—” pictured in 1866 and in 1870 after treatment. She was one of the earliest Anorexia nervosa case studies. The term anorexia nervosa was established in 1873 by Sir William Gull, one of Queen Victoria’s personal physicians. The term is of Greek origin: an- (prefix denoting negation) and orexis (appetite). | Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Linguistics, food, drinks, restaurants, health | September 21st, 2011 5:47 pm

Are you a verbal learner or a visual learner? Chances are, you’ve pegged yourself or your children as either one or the other. (…) But does scientific research really support the existence of different learning styles, or the hypothesis that people learn better when taught in a way that matches their own unique style?

Unfortunately, the answer is no, according to a major new report.

{ APS | Continue reading }

Linguistics, psychology | September 21st, 2011 5:42 pm

When we think about Mozart, Einstein, Michael Jordan, Bill Gates or Steve Jobs (or any other hugely successful person) we usually think about how smart they are, not how hard they worked. This creates the illusion that said individuals got to the top because they had something other people didn’t – some sort of genius. The more accurate picture is that their perseverance, work ethic and pure passion for what they did separated them from the rest of us. Unfortunately, as per Dweck’s study, kids praised for being “smart” don’t push themselves to achieve as much as they could because they believe intelligence alone breeds success. This belief causes them to fear failure, which moreover prohibits them from accomplishing and learning more. (…)

Mistakes are an essential component to learning. Learning about cognitive biases and irrational tendencies is vital, but appreciating failure and having a willingness to be wrong – to be irrational – is also essential.

{ Why We Reason | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | September 21st, 2011 8:38 am

In 1986, CEO of Perrier North America Bruce Nevins found himself in a difficult spot. On KABC radio in Los Angeles the host challenged him to a blind taste test. The rules were simple: correctly identify a Perrier from seven drinks – six club sodas and one Perrier. Long story short, Nevins failed miserably; it took him not one or two, but five tries before he picked out the Perrier.

I stole this example from Yale psychologist Paul Bloom, author of How Pleasure Works to reinforce a point I made a few posts ago: how you taste something strongly depends on what you believe you are tasting.

{ The Psychology of Pleasure: Interview With Paul Bloom | Continue reading }

painting { Rubens, Cimon and Pero, c.1630 | At first this seems a strange subject for a painting: a young woman giving her breast to an old man tied up in chains in a bare prison cell. In fact it is a story from Roman history: the tale of Cimon and Pero. Cimon is Pero’s father. He is in prison awaiting execution and has been given nothing to eat. Pero has recently had a child and saves her father from starvation by secretly giving him her breast. This relatively large picture was painted by the famous Antwerp artist, Peter Paul Rubens. To enliven the scene, Rubens has added two prying prison guards on the right. }

ideas, psychology | September 20th, 2011 8:07 am

Historically, the international significance of a language has depended on four key factors: demography (that is, the number of native speakers of the language in question); the military might of the native speakers; the economic power of the native speakers; and, finally, the cultural or political significance of what was written in the language.

Nicholas Ostler suggests that, in the 21st century, the military factor will be replaced by new technological and political factors: translation technology is going to help people communicating in different languages, while nationalistic claims in favour of certain languages will limit the spread of English and other contenders for the role of lingua franca. David Graddol, in his comprehensive report for the British Council, gives priority to the demographic factors and stresses the growth of global, post-modern multilingualism.

The foothold of the English language in North America after the multinational colonization that started in the early 17th century was attributed by 19th century commentators in part to the technical and aesthetic virtues of English – its clarity and grammatical simplicity – just as the past pre-eminence of French in Europe was due to its diplomatic polyvalence.

As for Russian, the life expectancy of Russians has been declining since the 1970s, and it is well established that Russia’s fertility rate is among the lowest in the world. The population of Russia is expected to fall by 30 to 50 million by the year 2050, resulting in a national headcount of around 100 million people, as against today’s 141 million. Although the anomalous mortality rate of the Russian male population may be reversed in the next few decades if social conditions improve, the overall demographic trend is unlikely to change – notwithstanding recent pro-fertility measures introduced by Prime Minister Putin. By contrast, the world’s population is expected to grow by almost one and half times by 2050.

{ Global Brief | Continue reading }

related { How Much Can You Say in 140 Characters? A Lot, if You Speak Japanese }

Linguistics, within the world | September 16th, 2011 8:15 am

People directly experience only the here and now. It is impossible to experience the past and the future, other places, other people, and alternatives to reality. And yet, memories, plans, predictions, hopes, and counterfactual alternatives populate our minds, influence our emotions, and guide our choice and action. How do we transcend the here and now to include distal entities? How do we plan for the distant future, understand other people’s point of view, and take into account hypothetical alternatives to reality? Construal level theory (CLT) proposes that we do so by forming abstract mental construals of distal objects.

Thus, although we cannot experience what is not present, we can make predictions about the future, remember the past, imagine other people’s reactions, and speculate about what might have been. Predictions, memories, and speculations are all mental constructions, distinct from direct experience. They serve to transcend the immediate situation and represent psychologically distant objects.

Psychological distance is a subjective experience that something is close or far away from the self, here, and now. Psychological distance is thus egocentric: Its reference point is the self, here and now, and the different ways in which an object might be removed from that point—in time, space, social distance, and hypotheticality—constitute different distance dimensions.

According to CLT, then, people traverse different psychological distances by using similar mental construal processes.

{ Construal-Level Theory of Psychological Distance | PubMed | Continue reading }

artwork { Morten Hemmingsen }

psychology, theory | September 15th, 2011 5:20 pm