ideas

In the 1950s, in the midst of what came to be known as the Economic Miracle, West Germany was positively deluged with other wonders: mysterious healings, mystical visions, rumors of the end of the world, and stories of divine and devilish interventions in ordinary lives. Scores of citizens of the Federal Republic (as well as Swiss, Austrians, and others from neighboring countries) set off on pilgrimages to see the Virgin Mary, Jesus, and hosts of angels, after they began appearing to a group of children in the southern German village of Heroldsbach in late 1949. Hundreds of thousands more journeyed from one end of the Republic to the other in the hopes of meeting a wildly popular faith healer, Bruno Gröning, who, some said, healed illness by banishing demons. Still others availed themselves of the skills of local exorcists in an effort to remove evil spirits from their bodies and minds. There also appears to have been an eruption of witchcraft accusations—neighbor accusing neighbor of being in league with the devil—accompanied by a corresponding upsurge in demand for the services of un-bewitchers (Hexenbanner). In short, the 1950s was a time palpably suffused with the presence of good and evil, the divine and the demonic, and in which the supernatural played a considerable role in the lives of many people.

Scholars across a variety of disciplines have raised important questions about the epistemological and methodological capacities of the social sciences to capture the lived reality of otherworldly encounters, past and present. (…)

Why do supernatural experiences matter for history?

{ Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture | Continue reading }

artwork { Andy Warhol, One multicolored Marylin, 1979 | acrylic and silkscreen on canvas }

flashback, ideas, weirdos | November 3rd, 2011 4:44 pm

Reductio ad absurdum and slippery slope: Two sides of the same coin? (…)

The overall argument of Hobbes’s Leviathan is a classic example that arguably lends itself to analysis via both of the two argument forms. The general outline of Hobbes’s argument is as follows: to prove that government is necessary, Hobbes assumes the opposite—suppose that we have a state of no government, what he calls a “state of nature.” Hobbes then argues that this situation entails absurdities, or consequences that no reasonable person would find tolerable. In Hobbes’s words, it would be a “constant state of war, of one with all.” (…)

Hobbes’s argument again seems clearly to be understandable as possessing the form of a reductio ad absurdum. (…)

If Hobbes is making a nominalist argument, wherein the conclusions reached are reached through conceptual analysis, one might well be prepared to concede that the argument is of the reductio ad absurdum form. But if, on the other hand, the argument is conceived to be making claims about the actual world and events that would/will/might happen therein, the argument can only be conceived of as offering an account of a slippery slope, and, in fact, one in which the slip could be stopped.

{ Annales Philosophici | Continue reading | PDF }

Linguistics, ideas | November 3rd, 2011 4:20 pm

We have the rise of the two-earner household and so previously if you just had the head of household working, and the head of household lost his job, it was less of an issue to move. Now if you have both members of the couple working and one of them loses their job, it’s very problematic to try to locate and try to find a better opportunity for both people. That’s one of the things that’s sort of been supporting large cities. If you look at what the data says–there’s been kind of a lot of work on this in the past two decades–it suggests, especially in recent decades, density has become quite important for improving productivity. (…) When a particular industry has a lot of participants in one geographical location, the whole industry gets better. It’s not just that there’s more competition, although that’s part of it, but that there’s a lot of cross-pollination of ideas between the participants, new spin-offs get started; so many aspects of that process take place in Silicon Valley, one of the examples you use, Boston, and other places like that; or in New York, the finance sector–some of them not so healthy–but a lot of innovations taking place that are harder to take place in geographically disparate locations. (…)

Places like New York, Boston, Washington, the Bay area–these are places that have been incredibly economically successful over the last ten years, and I think a lot of that is due to the way a lot of new technology has supported the high levels of human capital that they have. Made those places more productive. What’s striking is that this economic success, growth in wages, employment, to some extent, has not translated into a lot of population growth. In fact, quite the opposite. There has been some population growth there but most of that is due to natural increase or immigration. (…)

There’s been some interesting research on this lately which is that essentially there was no surplus labor in Silicon Valley in the late 1990s. Pretty low unemployment rate, like 2-3%. That was great for the workers who could afford to be there. Salaries were skyrocketing. But it was very difficult to attract new people. You wonder why, if salaries are going up so much, why wouldn’t people just be flooding into this market and taking advantage of that; and that’s because housing prices were growing even faster than compensation. So even as the tech industry was booming, people were leaving Silicon Valley. I think what’s interesting about that is that it put a chill on entrepreneurship; made it very lucrative to stay at a place that was established, to keep piling up stock options. It was much better to be a salaried worker than to be self-employed, so the rate of entrepreneurship in Silicon Valley at this point was much lower than the national average. You have a place that’s producing some of the best ideas; it’s a center for innovation; and it’s important that we start new businesses in the center of innovation–that’s what the research tells us. And yet it was very unattractive to start a new business at that point because the labor market was so tight, thanks to the tightness of the housing market.

{ Ryan Avent/EconTalk | Continue reading }

U.S., economics, ideas, new york | October 31st, 2011 3:17 pm

[In Time, 2011, directed by Andrew Niccol.]

Time is money: Everyone is genetically engineered to stop aging at 25; after that, people will live for only one more year unless they can gain access to more hours, days, weeks, etc. A cup of coffee costs four minutes, lunch at an upscale restaurant eight-and-a-half weeks. The distribution of wealth is about as lopsided as it is today, with the richest having at least a century remaining and the poorest surviving minute to minute. Each individual’s value is imprinted on the forearm as a clock, a string of 13 neon-green digits that suggests a cross between a concentration camp tattoo and a rave glow stick.

{ Village Voice | Overcoming Bias }

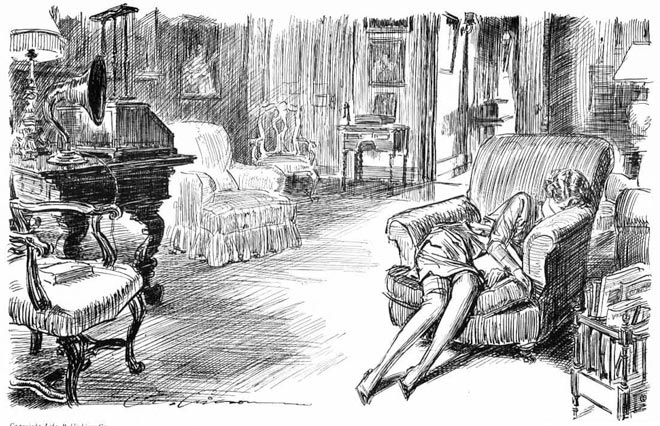

artwork { Charles Dana Gibson, Bedtime Story }

ideas, showbiz, time | October 31st, 2011 2:05 pm

The Tim Geoghegan Club, Where everybody knows your name

The Tavistock Hotel in London was the setting for a historic meeting in 1998. Tim Geoghegan of Brooklyn, USA met Tim Geoghegan of Stroud, England. The two men had corresponded via email prior to meeting face-to-face.

Membership in the Tim Geoghegan Club is limited to individuals with the legal name of Timothy Geoghegan, or individuals who wish to become a Tim Geoghegan.

{ Timgeoghegan.com }

photo { Kate Perers }

Onomastics, haha | October 30th, 2011 2:35 pm

This article examines the role of storytelling in the process of making sense of the financial crisis.

Taken for granted assumptions were suddenly open to question. Financial products and practices that were once assumed to be sustainable sources of economic growth and prosperity swiftly became de-legitimized. Highly respected individuals and institutions (bankers, regulators) suddenly became widely detested.

The moral stories crafted during a public hearing in the UK that was designed to uncover ‘what (or who) went wrong’ during the recent financial crisis are examined. Micro-linguistic tools were used to build different emplotments of the ‘story’ of the financial crisis and paint a picture of the key characters, for example as ‘villains’ or ‘victims.’ The stories told by the bankers had assigned responsibility for the crisis and what should be done about it. These stories shaped both public opinion and policy responses.

The study illustrates when a crisis of sensemaking occurs, and the dominant and well-established storyline is no longer plausible a new story must be crafted to make sense of what happened and why.

The plot and characters of a story start to form a meaningful story only when discursive devices (linguistic styles, phrases, tropes and figures of speech) build up a moral landscape within which the events unfold.

{ Bankers in the dock: Moral storytelling in action | SAGE | full article }

economics, ideas | October 28th, 2011 12:00 pm

Finding the right problem is half the solution

Everyone knows that finding a good problem is the key to research, yet no one teaches us how to do that. Engineering education is based on the presumption that there exists a predefined problem worthy of a solution. If only it were so!

After many years of managing research, I’m still not sure how to find good problems. Often I discovered that good problems were obvious only in retrospect, and even then I was sometimes proved wrong years later. Nonetheless, I did observe that there were some people who regularly found good problems, while others never seemed to be working along fruitful paths. So there must be something to be said about ways to go about this.

{ IEEE Spectrum | Continue reading }

photo { Yosuke Yajima }

ideas | October 28th, 2011 11:31 am

Venus and Adonis is a poem by William Shakespeare, written in 1592–1593, with a plot based on passages from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. It is a complex, kaleidoscopic work, using constantly shifting tone and perspective to present contrasting views of the nature of love.

The poem contains what may be Shakespeare’s most graphic depiction of sexual excitement.

Venus and Adonis comes from the 1567 translation by Arthur Golding of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book 10. Ovid told of how Venus took the beautiful Adonis as her first mortal lover. They were long-time companions, with the goddess hunting alongside her lover. She warns him of the tale of Atalanta and Hippomenes to dissuade him from hunting dangerous animals; he disregards the warning, and is killed by a boar. Shakespeare developed this basic narrative into a poem of 1,194 lines. His chief innovation was to make Adonis refuse Venus’s offer of herself.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

And at his look she flatly falleth down

For looks kill love, and love by looks reviveth;

A smile recures the wounding of a frown;

But blessed bankrupt, that by love so thriveth!

The silly boy, believing she is dead

Claps her pale cheek, till clapping makes it red;

(…)

He wrings her nose, he strikes her on the cheeks,

He bends her fingers, holds her pulses hard,

He chafes her lips; a thousand ways he seeks

To mend the hurt that his unkindness marr’d:

He kisses her; and she, by her good will,

Will never rise, so he will kiss her still.

{ Venus and Adonis | full text }

books, poetry | October 28th, 2011 11:15 am

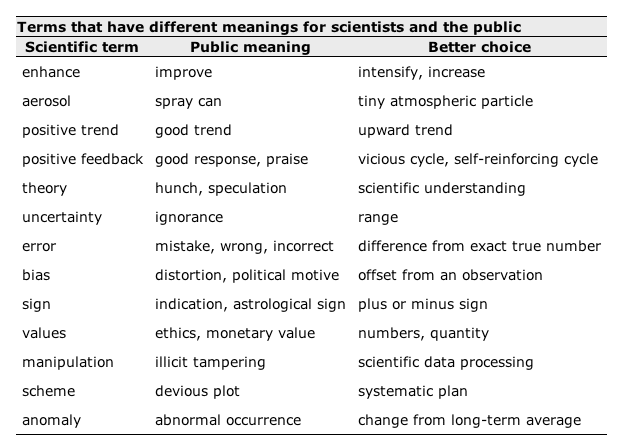

Linguistics, science | October 28th, 2011 11:10 am

Are there really such things as artistic masterworks? That is, do works belong to the artistic canon because critics and museum curators have correctly discerned their merits? (…)

For the sake of this discussion let’s focus on two possible views: the first, call it Humeanism, is the view that when we make evaluative judgements of artworks, we are sensitive to what is good or bad. On this Humean view, the works that form the artistic canon are there for good reason. Over time, critics, curators, and art historians arrive at a consensus about the best works; these works become known as masterworks, are widely reproduced, and prized as highlights of museum collections.

However, a second view—call it scepticism—challenges these claims about the role of value in both artistic judgement and canon formation. A sceptic will point to other factors that can sway critics and curators such as personal or political considerations, or even chance exposure to particular works, arguing that value plays a much less important role than the Humean would lead us to believe. According to such a view, if a minor work had fallen into the right hands, or if a minor painter had had the right connections, the artistic canon might have an entirely different shape.

How is one to determine whether we are sensitive to value when we form judgements about artworks? In a 2003 study, psychologist James Cutting briefly exposed undergraduate psychology students to canonical and lesser-known Impressionist paintings (the lesser-known works exposed four times as often), with the result that after exposure, subjects preferred the lesser-known works more often than did the control group. Cutting took this result to show that canon formation is a result of cultural exposure over time.

{ Experimental Philosophy | Continue reading }

arwtork { Marlene Dumas, Dead Girl, 2002 }

art, ideas | October 25th, 2011 2:21 pm

Far be it from me to suggest the abolition of sociology departments. After all, I’m the chairman of one.

But even a chairman would need an inhuman capacity for denial to fail to see that:

1. The overwhelming amount of current sociology is simply nonsense–tendentious nonsense at that.

2. Nearly all of the sociology that is not tendentious nonsense is so obvious that one wonders why anyone would see the need to demonstrate it.

{ Steven Goldberg | Continue reading }

ideas | October 24th, 2011 1:56 pm

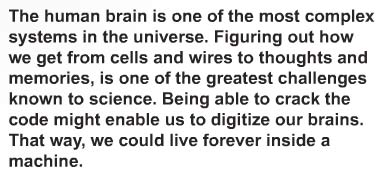

future, ideas, time | October 24th, 2011 7:42 am

ideas, science | October 24th, 2011 7:13 am

If one could rewind the history of life, would the same species appear with the same sets of traits? Many biologists have argued that evolution depends on too many chance events to be repeatable. But a new study investigating evolution in three groups of microscopic worms, including the strain that survived the 2003 Columbia space shuttle crash, indicates otherwise. When raised in a lab under crowded conditions, all three underwent the same shift in their development by losing basically the same gene. The work suggests that, to some degree, evolution is predictable.

{ Nature | Continue reading }

images { Jesse Richards | Susan Rothenberg }

science, theory | October 24th, 2011 7:05 am

Hume’s account of the self is to be found mainly in one short and provocative section of his Treatise of Human Nature – a landmark work in the history of philosophy, published when Hume was still a young man. What Hume says here (in “Of Personal Identity”) has provoked a philosophical debate which continues to this day. What, then, is so novel and striking about Hume’s account that would explain its fascination for generations of philosophers?

One of the problems of personal identity has to do with what it is for you to remain the same person over time. In recalling your childhood experiences, or looking forward to your next holiday, it appears that in each case you are thinking about one and the same person – namely, you. But what makes this true? The same sort of question might be raised about an object such as the house in which you’re now living. Perhaps it has undergone various changes from the time when you first moved in – and you may have plans to alter it further. But you probably think that it is the same house throughout. So how is this so? It helps in this case that at least we’re pretty clear about what it is for something to be a house (namely, a building with a certain function), and therefore to be the same house through time. But what is it for you to be a person (or self)? This is the question with which Hume begins. He is keen to dismiss the prevailing philosophical answer to this question – (…) that underlying our various thoughts and feelings is a core self: the soul, as it is sometimes referred to. (…)

How, then, does Hume respond to this view of the self? (…) Hume concludes memorably that each of us is “nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions”. We might be inclined to think of the mind as a kind of theatre in which our thoughts and feelings – or “perceptions” – make their appearance; but if so we are misled, for the mind is constituted by its perceptions. This is the famous “bundle” theory of the mind or self that Hume offers as his alternative to the doctrine of the soul.

{ The Philosophers’ Magazine | Continue reading }

ideas | October 17th, 2011 1:20 pm

What is the art of immersion? The focus of the book is on how the internet is changing storytelling; and the idea is really that every time a new medium comes along, it takes people 20 or 30 years to figure out what to do with it, to figure out the grammar of that medium. The motion picture camera was invented around 1890 and it was really about 1915 before the grammar of cinema–all the things we take for granted now, like cuts and point-of-view shots and fades and pans–were consolidated into first what we would recognize as feature films. Birth of a Nation being the real landmark. It wasn’t the first film that had these characteristics but it was the first film to use all of them and that people settled on that really made a difference. I think we are not quite there yet with the internet but we can see the outlines of what is happening, what is starting to emerge; and it’s very different from the mass media that we’ve been used to for the past 150 years. (…)

NotSoSerious.com–the campaign in advance of the Dark Knight. This was what’s known as an alternate reality game. This was a particularly large-scale example that took place over a period of about 18 months. Essentially the purpose of it was to create this experience that kind of started and largely played out online but also in the real world and elsewhere that would familiarize people with the story and the characters of the Dark Knight. In particular with Heath Ledger as the Joker. Build enthusiasm and interest in the movie in advance of its release. On one level it was a marketing campaign; on another level it was a story in itself–a whole series of stories. It was developed by a company called 42 Entertainment, based in Pasadena and headed by a woman named Susan Bonds who was interestingly enough educated and worked first as a Systems Engineer and spent quite a bit of time at Walt Disney Imagineering, before she took up this. It’s a particularly intriguing example of storytelling because it really makes it possible or encourages the audience to discover and tell the story themselves, online to each other. For example, there was one segment of the story where there were a whole series of clues online that led people to a series of bakeries in various cities around the United States. And when the got to the bakery, the first person to get there in each of these cities, they were presented with a cake. On the icing to the cake was written and phone number and the words “Call me.” When they called, the cake started ringing. People would obviously cut into the cake to see what was going on, and inside the cake they found a sealed plastic pouch with a cell phone and a series of instructions. And this led to a whole new series of events that unfolded and eventually led people to a series of screenings at cities around the country of the first 7 minutes of the film, where the Heath Ledger character is introduced. (…)

The thing about Lost was it was really a different kind of television show. What made it different was not the sort of gimmicks like the smoke monster and the polar bear–those were just kind of icing. What really made it different was that it wasn’t explained. In the entire history of television until quite recently, just the last few years, the whole idea of the show has been to make it really simple, to make it completely understandable so that no one ever gets confused. Dumb it down for a mass audience. Sitcoms are just supposed to be easy. Right. Lost took exactly the opposite tack, and the result was–it might not have worked 10 years ago, but now with everybody online, we live in an entirely different world. The result was people got increasingly intrigued by the essentially puzzle-like nature of the show. And they tended to go online to find out things about it. And the show developed a sort of fanatical following, in part precisely because it was so difficult to figure out.

There was a great example I came across of a guy in Anchorage, Alaska who watched the entire first season on DVD with his girlfriend in a couple of nights leading up to the opening episode of Season 2. And then he watched the opening episode of Season 2 and something completely unexpected happened. What is going on here? So he did what comes naturally at this point, which was to go online and find out some information about it. But there wasn’t really much information to be found, so he did the other thing that’s becoming increasingly natural, which was he started his own Wiki. This became Lostpedia–it was essentially a Wikipedia about Lost and it now has tens of thousands of entries; it’s in about 20 different languages around the world. And it’s become such a phenomenon that occasionally the people who were producing the show would themselves consult it–when their resident continuity guru was not available.

What had been published in very small-scale Fanzines suddenly became available online for anybody to see. (…)

The amount of time people devote to these beloved characters and stories–which are not real, which doesn’t matter really at all, which was one of the fascinating things about this whole phenomenon–it couldn’t have happened in 1500. Not because of the technology–of course they are related–but you’d starve to death. The fact that people can devote hundreds of hundreds of hours personally, and millions can do this says something about modern life that is deep and profound. Clay Shirky, who I believe you’ve interviewed in the past, has the theory that television arrived just in time to soak up the excess leisure time that was produced by the invention of vacuum cleaners and dishwashers and other labor-saving devices.

{ Frank Rose/EconTalk | Continue reading }

ideas, marketing, media, showbiz | October 17th, 2011 1:00 pm

Today hardly anyone notices the equinox. Today we rarely give the sky more than a passing glance. We live by precisely metered clocks and appointment blocks on our electronic calendars, feeling little personal or communal connection to the kind of time the equinox once offered us. Within that simple fact lays a tectonic shift in human life and culture.

Your time — almost entirely divorced from natural cycles — is a new time. Your time, delivered through digital devices that move to nanosecond cadences, has never existed before in human history. As we rush through our overheated days we can barely recognize this new time for what it really is: an invention. (…)

Mechanical clocks for measuring hours did not appear until the fourteenth century. Minute hands on those clocks did not come into existence until 400 years later. Before these inventions the vast majority of human beings had no access to any form of timekeeping device. Sundials, water clocks and sandglasses did exist. But their daily use was confined to an elite minority.

{ Adam Frank/NPR | Continue reading }

The 12-hour clock can be traced back as far as Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: Both an Egyptian sundial for daytime use and an Egyptian water clock for night time use were found in the tomb of Pharaoh Amenhotep I. Dating to c. 1500 BC, these clocks divided their respective times of use into 12 hours each.

The Romans also used a 12-hour clock: daylight was divided into 12 equal hours (of, thus, varying length throughout the year) and the night was divided into four watches. The Romans numbered the morning hours originally in reverse. For example, “3 am” or “3 hours ante meridiem” meant “three hours before noon,” compared to the modern usage of “three hours into the first 12-hour period of the day.”

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Also: The terms “a.m.” and “p.m.” are abbreviations of the Latin ante meridiem (before midday) and post meridiem (after midday).

Linguistics, flashback, time | October 17th, 2011 8:36 am

My topic is the shift from ‘architect’ to ‘gardener’, where ‘architect’ stands for ’someone who carries a full picture of the work before it is made’, to ‘gardener’ standing for ’someone who plants seeds and waits to see exactly what will come up’. I will argue that today’s composer are more frequently ‘gardeners’ than ‘architects’ and, further, that the ‘composer as architect’ metaphor was a transitory historical blip.

{ Brian Eno/Edge }

photos { Sid Avery, Sammy Davis Jr, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra and Joey Bishop Stage a Fight During the Making of Ocean’s Eleven }

ideas, music | October 14th, 2011 1:20 pm

Kings, queens and dukes were always richer and more powerful than the population at large, and would surely have liked to use their money and power to lengthen their lives, but before 1750 they had no effective way of doing so. Why did that change? While we have no way of being sure, the best guess is that, perhaps starting as early as the 16th century, but accumulating over time, there was a series of practical improvements and innovations in health. (…)

The children of the royal family were the first to be inoculated against smallpox (after a pilot experiment on condemned prisoners), and Johansson notes that “medical expertise was highly priced, and many of the procedures prescribed were unaffordable even to the town-dwelling middle-income families in environments that exposed them to endemic and epidemic disease.” So the new knowledge and practices were adopted first by the better-off—just as today where it was the better-off and better-educated who first gave up smoking and adopted breast cancer screening. Later, these first innovations became cheaper, and together with other gifts of the Enlightenment, the beginnings of city planning and improvement, the beginnings of public health campaigns (e.g. against gin), and the first public hospitals and dispensaries, they contributed to the more general increase in life chances that began to be visible from the middle of the 19th century.

Why is this important? The absence of a gradient before 1750 shows that there is no general health benefit from status in and of itself, and that power and money are useless against the force of mortality without weapons to fight. (…)

Men die at higher rates than women at all ages after conception. Although women around the world report higher morbidity than men, their mortality rates are usually around half of those of men. The evidence, at least from the US, suggests that women experience similar suffering from similar conditions, but have higher prevalence of conditions with higher morbidity, and lower prevalence of conditions with higher mortality so that, put crudely, women get sick and men get dead.

{ Angus Deaton, Center for Health and Wellbeing, Princeton University | Continue reading | PDF }

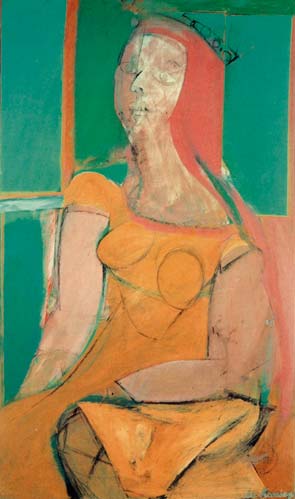

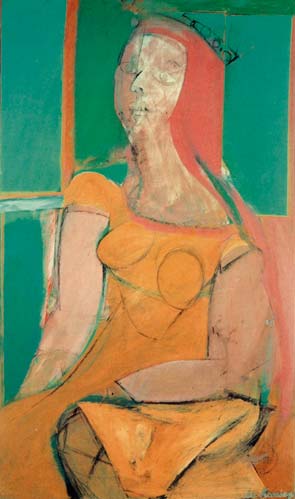

artwork { Willem de Kooning, Queen of Hearts, 1943-46 }

flashback, health, ideas | October 14th, 2011 1:08 pm

“Literally’’ (…)

It’s a word that has been misused by everyone from fashion stylist Rachel Zoe to President Obama, and linguists predict that it will continue to be led astray from its meaning. There is a good chance the incorrect use of the word eventually will eclipse its original definition.

What the word means is “in a literal or strict sense.’’ Such as: “The novel was translated literally from the Russian.’’

“It should not be used as a synonym for actually or really,’’ writes Paul Brians in “Common Errors in English Usage.’’

{ Boston Globe | Continue reading }

Linguistics | October 14th, 2011 12:26 pm