ideas

The three most disruptive transitions in history were the introduction of humans, farming, and industry. If another transition lies ahead, a good guess for its source is artificial intelligence in the form of whole brain emulations, or “ems,” sometime in roughly a century.

{ Overcoming Bias | Continue reading }

A case can be made that the hypothesis that we are living in a computer simulation should be given a significant probability. The basic idea behind this so-called “Simulation argument” is that vast amounts of computing power may become available in the future, and that it could be used, among other things, to run large numbers of fine-grained simulations of past human civilizations. Under some not-too-implausible assumptions, the result can be that almost all minds like ours are simulated minds, and that we should therefore assign a significant probability to being such computer-emulated minds rather than the (subjectively indistinguishable) minds of originally evolved creatures. And if we are, we suffer the risk that the simulation may be shut down at any time.

{ Nick Bostrom | Continue reading | Related: Nick Bostrom, Are you living in a computer simulation?, 2003 }

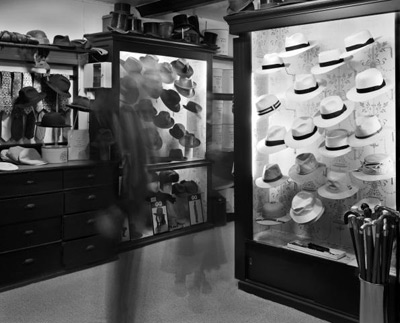

photo { Matthew Pillsbury }

future, ideas, photogs, technology | November 17th, 2012 3:44 am

Rousseau at fifty-three — afflicted by illness, temperamental and alone, an anguished, paranoiac conscience — sitting up at his desk in Wootton, in the 1760s: “Nothing about me must remain hidden or obscure. I must remain incessantly beneath the reader’s gaze, so that he may follow me in all the extravagances of my heart and into every last corner of my life.”

The Confessions are Rousseau’s response, in the form of a remedy, to the pain and contradictions of a human heart filled with content that can no longer be transmitted vertically, toward the heavens. The task of the accused to supply proof of innocence, to authenticate the rightness of his conduct, requires a new, lateral kind of divination. A community of readers, not saints, is what counts.

{ Ricky D’Ambrose/TNI | Continue reading }

photo { Brittany Markert }

ideas, photogs | November 16th, 2012 12:47 pm

This article looks in more depth at the different ways in which ideas about cashless societies were articulated and explored in pre-1900 utopian literature. Taking examples from the works of key writers such as Thomas More, Robert Owen, William Morris and Edward Bellamy, it discusses the different ways in which the problems associated with conventional notes-and-coins monetary systems were tackled as well as looking at the proposals for alternative payment systems to take their place. Ultimately, what it shows is that although the desire to dispense with cash and find a more efficient and less-exploitable payment system is certainly nothing new, the practical problems associated with actually implementing such a system remain hugely challenging.

{ MPRA/Academia | Continue reading }

economics, ideas | November 16th, 2012 3:55 am

I think we felt that happiness, the ideal of happiness, making happiness the goal of life is very vacuous. We thought rather that happiness is a subjective state of feeling. And if what you want to do is maximize this subjective state of feeling–being happy–then I think all you have to do is invent a psychic aspirin that makes you happy the whole time. I think drug dealers sort of promise something like that as well. But you wouldn’t want to say about someone made perpetually happy by being drugged or taking pills that that person is leading a good life. I think there’s a moral objection to that immediately comes. People will say: We were built for something else. We were made for something else; not to be idiotically happy the whole time. So, it’s the subjective element there that if you want to maximize happiness, you are really wanting to maximize just a state of feeling, divorced entirely from the pursuit of those things that would justifiably make you happy. I think that’s our main critique of happiness. Happiness is a byproduct of an achievement of doing something well, of realizing your potential, flourishing, and things of that kind.

{ Robert Skidelsky/EconTalk | Continue reading }

ideas | November 14th, 2012 10:11 am

James Joyce | November 6th, 2012 1:02 pm

In quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle is any of a variety of mathematical inequalities asserting a fundamental limit to the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties of a particle, such as position x and momentum p, can be known simultaneously. The more precisely the position of some particle is determined, the less precisely its momentum can be known, and vice versa. The original heuristic argument that such a limit should exist was given by Werner Heisenberg in 1927, after whom it is sometimes named, as the Heisenberg principle. […]

Historically, the uncertainty principle has been confused with a somewhat similar effect in physics, called the observer effect, which notes that measurements of certain systems cannot be made without affecting the systems.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

photo { Jason Lazarus }

ideas, photogs, science | November 5th, 2012 2:50 pm

Assume that you can’t redistribute happiness or wealth within the marriage. If your spouse is unhappy you will be unhappy and if your spouse is happy you are likely to be happy; happy wife, happy life.

If you can’t redistribute happiness the play to make is to maximize total happiness. Maximizing total happiness means accepting apparent reductions in happiness when those result in even larger increases in happiness for your spouse. If you maximize the total, however, there will be more to go around and the reductions will usually be temporary.

{ Marginal Revolution | Continue reading }

photo { Sergiy Barchuk }

guide, ideas, relationships | November 4th, 2012 8:28 am

Every several years, IQ tests test have to be “re-normed” so that the average remains 100. This means that a person who scored 100 a century ago would score 70 today; a person who tested as average a century ago would today be declared mentally retarded. […]

Do rising IQ scores really mean we are getting smarter? […]

Implicit in Flynn’s argument that we are becoming “more modern” is that IQ gains are due to environmental factors, not genetic ones. […] He invokes environmental factors, for example, to explain the shrinking male/female IQ gap and debunk notions of innate differences in intelligence between men and women. He uses similar reasoning to explain IQ differences between developed and developing countries.

{ TNR | Continue reading }

photo { Johan Willner }

ideas, science, within the world | October 26th, 2012 9:18 am

Paul Ehrlich gave a talk at Stanford titled “Can a Collapse be Avoided”? Ehrlich is a biologist but his interests spread to Economics and Technology as well. The “collapse” of his talk is the catastrophe that, according to most climate scientists, is rapidly approaching. He listed eight major environmental problems and briefly discussed each. Some of them need no introduction (extinction of species, climate change, pollution) but others are no less catastrophic even though less advertised.

For example, global toxification: we filled the planet with toxis substances, and therefore the odds that some of them interact/combine in some deadly chemical experiment never tried before are increasing exponentially every year. There is no known way to fix something like that. We know how to fix pollution and carbon emissions and so forth (if we wanted to), but science would not know how to deal with a chemical reaction triggered by the combination of toxic substances in the soil. The highlight of the talk for me was the emphasis on “non-linearity”. Many scientists point out the various ways in which humans are hurting our ecosystem, but few single out the fact that some of these ways may combine and become something that is more lethal than the sum of its parts.

Another interesting point that is not widely recognized is that the next addition of one billion people to the population of the planet will have a much bigger impact on the planet than the previous one billion. The reason is that human civilizations already used up all the cheap, rich and ubiquitous resources. Naturally enough, humans started with the cheap, rich and ubiquitous ones, whether forests or oil wells. A huge amount of resources is still left, but those will be much more difficult to harness. For example, oil wells have to be much deeper than they used to. Therefore one liter of gasoline today does not equal one liter of gasoline a century from now: a century from now they will have to do a lot more work to get that liter of gasoline. That was the second key point that struck me: it is not only that some resources are being depleted, but even the resources that will be left are, by definition, those that are difficult to extract and use (a classic case of diminishing margin of return).

The bottom line of these arguments is that the collapse is not only coming, but the combination of the eight factors plus the internal combinations in each of them make it likely that it is coming even sooner than pessimists predict.

{ Piero Scaruffi | Continue reading }

future, ideas, incidents | October 25th, 2012 11:48 am

How could I successfully kill a clone that is always thinking the exact same thing I am?

[…]

Kill yourself.

{ Quora | more answers }

photo { Mark Powell }

ideas, photogs | October 24th, 2012 2:58 pm

Over time, we have grown increasingly vulnerable to natural disasters. Each decade economic losses from such disasters more than double as people continue to build homes, businesses, and other physical infrastructure in hazardous places. Yet public policy has thus far failed to address the unique problems posed by natural disasters. […]

Drawing from philosophy, cognitive psychology, history, anthropology, and political science, this Article identifies and analyzes three categories of obstacles to disaster policy — symbolic obstacles, cognitive obstacles, and structural obstacles. The way we talk about natural disaster, the way we think about the risks of building in hazardous places, and structural aspects of American political institutions all favor development over restraint. Indeed, these forces have such strength that in most circumstances society automatically and thoughtlessly responds to natural disasters by beginning to rebuild as soon as a disaster has occurred.

{ SSRN | Continue reading }

photo { Ann James }

architecture, ideas, incidents | October 24th, 2012 2:52 pm

Adrian Wooldridge has an excellent column on how the advent of driverless cars might impact the global automotive industry and the broader economy. […]

When people are no longer in control of their cars they will not need driver insurance—so goodbye to motor insurers and brokers. Traffic accidents now cause about 2m hospital visits a year in America alone, so autonomous vehicles will mean much less work for emergency rooms and orthopaedic wards. Roads will need fewer signs, signals, guard rails and other features designed for the human driver; their makers will lose business too. When commuters can work, rest or play while the car steers itself, longer commutes will become more bearable, the suburbs will spread even farther and house prices in the sticks will rise. When self-driving cars can ferry children to and from school, more mothers may be freed to re-enter the workforce. The popularity of the country pub, which has been undermined by strict drink-driving laws, may be revived. And so on.

{ National Review | Continue reading }

photo { George Kelly }

economics, future, ideas, transportation | October 23rd, 2012 1:28 pm

A worrying trend has emerged in which a writer’s success has come to be measured by the number of views and comments elicited by his or her writing. Those same writers have, in a matter of a few years, adopted a new publishing ethos in which they post their thoughts, opinions, and writings on the plethora of blogging sites currently available. The generation of bloggers, many of whom started out as newspaper writers and later moved to electronic publishing, didn’t stop there—they expanded their commenting activity to their personal Facebook pages. […]

Facebook users find themselves in the position of a superstar or a prophet, needing to utter profound statements and expecting the cheers of the crowd. As it becomes easier and easier for people to connect, this loop tragically kills conversations and exchanges them for the proclamations of ignorant judges who know nothing of the world but their own personal narratives and verdicts.

{ e-flux | Continue reading }

ideas, media, social networks | October 22nd, 2012 10:56 am

This article examines cognitive links between romantic love and creativity and between sexual desire and analytic thought based on construal level theory. It suggests that when in love, people typically focus on a long-term perspective, which should enhance holistic thinking and thereby creative thought, whereas when experiencing sexual encounters, they focus on the present and on concrete details enhancing analytic thinking. Because people automatically activate these processing styles when in love or when they experience sex, subtle or even unconscious reminders of love versus sex should suffice to change processing modes. Two studies explicitly or subtly reminded participants of situations of love or sex and found support for this hypothesis.

{ Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin/SAGE | PDF }

ideas, psychology, relationships, sex-oriented | October 22nd, 2012 10:35 am

Implicit in the rationalist literature on bargaining over the last half-century is the political utility of violence. Given our anarchical international system populated with egoistic actors, violence is thought to promote concessions by lending credibility to their threats. In dyadic competitions between a defender and challenger, violence enhances the credibility of his threat via two broad mechanisms familiar to theorists of international relations. First, violence imposes costs on the challenger, credibly signaling resolve to fight for his given preferences. Second, violence imposes costs on the defender, credibly signaling pain to him for noncompliance (Schelling 1960, 1966). All else equal, this forceful demonstration of commitment and punishment capacity is believed to increase the odds of coercing the defender’s preferences to overlap with those of the challenger in the interest of peace, thereby opening up a proverbial bargaining space. Such logic is applied in a wide range of contexts to explain the strategic calculus of states, and increasingly, non-state actors.

From the vantage of bargaining theory, then, empirical research on terrorism poses a puzzle. For non-state challengers, terrorism does in fact signal a credible threat in comparison to less extreme tactical alternatives. In recent years, however, a spate of empirical studies across disciplines and methodologies has nonetheless found that neither escalating to terrorism nor with terrorism encourages government concessions. In fact, perpetrating terrorist acts reportedly lowers the likelihood of government compliance, particularly as the civilian casualties rise. The apparent tendency for this extreme form of violence to impede concessions challenges the external validity of bargaining theory, as traditionally understood. In Kuhnian terms, the negative coercive value from escalating represents a newly emergent anomaly to the reigning paradigm, inviting reassessment of it (Kuhn 1962).

That is the purpose of this study.

{ International Studies Quarterly | PDF }

related { Making China’s nuclear war plan | PDF }

fights, ideas, theory | October 19th, 2012 12:55 pm

If promises are binding, if they are cogent ways for people to bind themselves, there must be a reason to do as one promised. The paper is motivated by belief that there is a difficulty in explaining what that reason is, a difficulty that is not often noticed. It arises because the reasons that promising creates are content-independent. […]

To see the difficulty, think of an ordinary case: I have reason not to hit you, in fact there are a number of such reasons: it may injure you, it may cause you pain, invade your body, etc. They all depend on the nature of the action, its consequences and context. Now think of a reason arising out of a promise, say my reason to let you use my car tomorrow. The reason is that I promised to do so. But that very same reason applies to all my promises. If I promise to feed your cat next week, to come to your party, to send flowers in your name to your mother on Mother’s Day, to lend you my new DVD, or whatever the action I promise to perform (or to refrain from) the reason is the same: my promise. Of course, these are different promises. But normatively speaking they are the same, they are all binding on me because they are promises I made, regardless of what is the act promised. This is why they are (called) content-independent reasons. […]

One simple idea is that promises are binding qua promises (or rather that that is the only ground for their binding character of relevance here), and that they are promises because they are communications of an intention to undertake an obligation by that very communication, regardless of their content, regardless of which act or omission they are about. I suggested that there are exceptions; acts that one cannot promise to perform. For example, a promise (given in current circumstances) to exterminate homo sapiens or all primate species would not be binding. One may think that so long as such exceptions are rare they do not undermine the suggestion that promises are content-independent.

{ Joseph Raz/SSRN | Continue reading }

photo { Susan Worsham }

ideas, photogs, relationships | October 18th, 2012 1:52 pm

Usually people don’t agree with one another as much as they should. Aumann’s Agreement Theorem (AAT) finds:

…two people acting rationally (in a certain precise sense) and with common knowledge of each other’s beliefs cannot agree to disagree. More specifically, if two people are genuine Bayesian rationalists with common priors, and if they each have common knowledge of their individual posteriors, then their posteriors must be equal.

The surprising part of the theorem isn’t that people should agree once they have heard the rationale for each of their positions and deliberated on who is right. The amazing thing is that their positions should converge, even without knowing how the other reached their conclusion.

{ OvercomingBias | Continue reading }

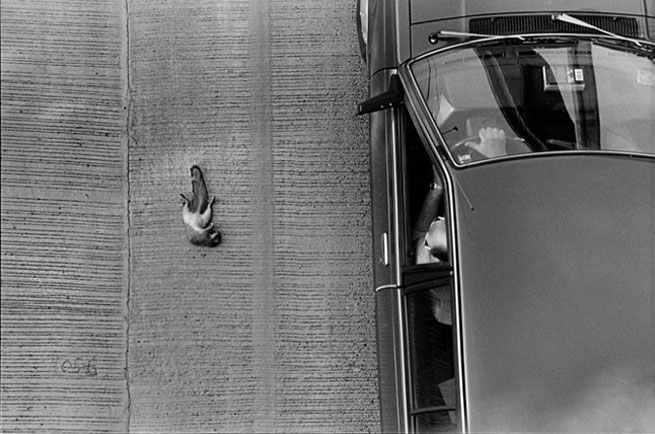

images { 1. Garry Winogrand | 2 }

ideas | October 18th, 2012 12:48 pm

In 1935, Erwin Schrödinger devised an insidious thought experiment. He imagined a box with a cat inside, which could be killed at any moment by a deadly mixture of radiation and poison. Or it might not be killed at all. Both outcomes were equally probable.

But the consequence of thinking through this situation was much more shocking than the initial setup. According to quantum theory, there wasn’t just one cat inside the box, dead or alive. There were actually two cats: one dead, one alive—both locked into a state of so-called superposition, that is, co-present and materially entangled with one another. This peculiar state lasted as long as the box remained closed.

Macrophysical reality is defined by either/or situations. Someone is either dead or alive. But Schrödinger’s thought experiment boldly replaced mutual exclusivity with an impossible coexistence—a so-called state of indeterminacy.

But that’s not all. The experiment becomes even more disorienting when the box is opened and the entanglement (Verschränkung) of the dead and the live cat abruptly ends. At this point, either a dead or a live cat decisively emerges, not because the cat then actually dies or comes to life, but because we look at it. The act of observation breaks the state of indeterminacy. In quantum physics, observation is an active procedure. By taking measure and identifying, it interferes and engages with its object. By looking at the cat, we fix it in one of two possible but mutually exclusive states. We end its existence as an indeterminate interlocking waveform and freeze it as an individual chunk of matter.

To acknowledge the role of the observer in actively shaping reality is one of the main achievements of quantum theory.

{ e-flux | Continue reading }

ideas | October 17th, 2012 10:31 am

Linguistics | October 17th, 2012 8:33 am

When humans evolved bigger brains, we became the smartest animal alive and were able to colonise the entire planet. But for our minds to expand, a new theory goes, our cells had to become less willing to commit suicide – and that may have made us more prone to cancer.

When cells become damaged or just aren’t needed, they self-destruct in a process called apoptosis. In developing organisms, apoptosis is just as important as cell growth for generating organs and appendages – it helps “prune” structures to their final form.

By getting rid of malfunctioning cells, apoptosis also prevents cells from growing into tumours. […]

McDonald suggests that humans’ reduced capacity for apoptosis could help explain why our brains are so much bigger, relative to body size, than those of chimpanzees and other animals. When a baby animal starts developing, it quickly grows a great many neurons, and then trims some of them back. Beyond a certain point, no new brain cells are created.

Human fetuses may prune less than other animals, allowing their brains to swell.

{ NewScientist | Continue reading }

brain, health, science, theory | October 15th, 2012 11:53 am