Decades of research have shown that humans are so-called cognitive misers. When we approach a problem, our natural default is to tap the least tiring cognitive process. Typically this is what psychologists call type 1 thinking, famously described by Nobel Prize–winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman as automatic, intuitive processes that are not very strenuous.

This is in contrast to type 2 thinking, which is slower and involves processing more cues in the environment. Defaulting to type 1 makes evolutionary sense: if we can solve a problem more simply, we can bank extra mental capacity for completing other tasks. A problem arises, however, when the simple cues available are either insufficient or vastly inferior to the more complex cues at hand.

Exactly this kind of conflict can occur when someone chooses to believe a personal opinion over scientific evidence or statistics.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

psychology |

November 3rd, 2015

Past research showed that people accumulate more knowledge about other people and objects they like compared to those they dislike. More knowledge is commonly assumed to lead to more differentiated mental representations; therefore, people should perceive others they like as less similar to one another than others they dislike.

We predict the opposite outcome based on the density hypothesis; accordingly, positive impressions are less diverse than negative impressions as there are only a few ways to be liked but many ways to be disliked. Therefore, people should perceive liked others as more similar to one another than disliked others even though they have more knowledge about liked others.

Seven experiments confirm this counterintuitive prediction and show a strong association between liking and perceived similarity in person perception.

{ Journal of Experimental Social Psychology | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships |

October 31st, 2015

What happens to us as we accrue knowledge and experience, as we become experts in a field? Competence follows. Effortlessness follows. But certain downsides can follow too. We reported recently on how experts are vulnerable to an overclaiming error – falsely feeling familiar with things that seem true of a domain but aren’t. Now a new paper in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology explores how feelings of expertise can lead us to be more dogmatic towards new ideas.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

buffoons, psychology |

October 31st, 2015

In Experiment 1 (N = 218), where female participants rated male facial attractiveness, the facilitative effect of smiling was present when judging long-term partners but absent for short-term partners. This pattern was observed for East Asians as well as for Europeans. […]

Related to this issue, Morrison et al. (2013) compared the attractiveness of faces displaying the six basic emotions (anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise). Faces with a happy expression were rated to be more attractive than faces with the other emotions, but they were rated as attractive as neutral ones.

{ Evolutionary Psychology | Continue reading }

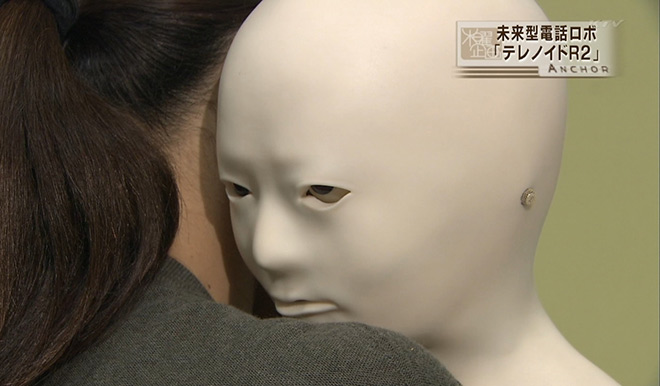

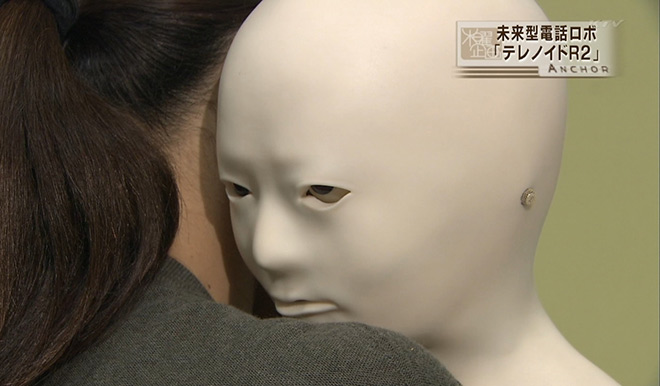

related { Transferring the expressions of one person’s face to the other in realtime }

faces, psychology, relationships |

October 27th, 2015

Group 1 - Carcinogenic:

This is the group for which there is the most evidence of cancer risk. […]

• Arsenic and arsenic compounds

[…]

• Solar radiation

• Tamoxifen6

• Tobacco, smoking, second-hand smoke

• Ultraviolet radiation

• X-Radiation and gamma radiation

• Processed meat

[…]

Group 2A - Probably carcinogenic:

Limited evidence of carcinogenicity in humans, sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in experimental animals. […]

• Shift work that disrupts sleep patterns

• Red meat

[…]

Group 2B - Possibly carcinogenic:

Limited evidence of carcinogenicity in humans, less than sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in experimental animals. […]

• Magenta dyes

• Pickled vegetables

{ Washington Post | Continue reading }

food, drinks, restaurants, poison, smoking |

October 26th, 2015

This research examines the role of alcohol consumption on self-perceived attractiveness. Study 1, carried out in a barroom (N= 19), showed that the more alcoholic drinks customers consumed, the more attractive they thought they were.

In Study 2, 94 non-student participants in a bogus taste-test study were given either an alcoholic beverage (target BAL [blood alcohol level]= 0.10 g/100 ml) or a non-alcoholic beverage, with half of each group believing they had consumed alcohol and half believing they had not (balanced placebo design). After consuming beverages, they delivered a speech and rated how attractive, bright, original, and funny they thought they were. The speeches were videotaped and rated by 22 independent judges. Results showed that participants who thought they had consumed alcohol gave themselves more positive self-evaluations. However, ratings from independent judges showed that this boost in self-evaluation was unrelated to actual performance.

{ British Journal of Psychology | PDF }

food, drinks, restaurants, psychology |

October 26th, 2015

Starting at age 55, our hippocampus, a brain region critical to memory, shrinks 1 to 2 percent every year, to say nothing of the fact that one in nine people age 65 and older has Alzheimer’s disease. The number afflicted is expected to grow rapidly as the baby boom generation ages. Given these grim statistics, it’s no wonder that Americans are a captive market for anything, from supposed smart drugs and supplements to brain training, that promises to boost normal mental functioning or to stem its all-too-common decline. […]

A few years back, a joint study by BBC and Cambridge University neuroscientists put brain training to the test. Their question was this: Do brain gymnastics actually make you smarter, or do they just make you better at doing a specific task? […] All subjects took a benchmark cognitive test, a kind of modified I.Q. test, at the beginning and at the end of the study. Although improvements were observed in every cognitive task that was practiced, there was no evidence that brain training made people smarter.

There was, however a glimmer of hope for subjects age 60 and above. Unlike the younger participants, older subjects showed a significant improvement in verbal reasoning, one of the components of the benchmark test, after just six weeks of brain training, so the older subjects continued in a follow-up study for a full 12 months.

Results of this follow-up study, soon to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, generally show that continued brain training helps older subjects maintain the improvement in verbal reasoning seen in the earlier study. This is good news because it suggests that brain exercise might delay some of the effects of aging on the brain.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

brain |

October 26th, 2015

Chinese ice cream is different, and those differences reflect a different economic and technological context. American ice cream is mainly sold by grocery stores in large containers to be eaten at home. So the basic assumption is that people have freezers at home in which to store the ice cream. Even when ice cream is sold on-the-go, it is sold out as scoops out of those big containers. But historically in China most people did not have freezers at home, though many more of them do now. Ice cream in China is therefore usually sold by convenience stores or roadside stalls, in small packages to be eaten immediately. So rather than big vats of ice cream, it is mostly individual bars.

These constraints have pushed innovation in Chinese ice cream in different directions. You can get all kinds of amazing wacky ice cream flavors in the US, but they are all delivered in mostly the same form: a tub of ice cream eaten with a spoon. Chinese ice cream innovates on form and texture more than with ingredients, with many bars featuring not just crunchy outer layers of chocolate but interior elements made of various yummy substances.

The structural complexity of some ice-cream bars is so great that it’s common for the package to have a 3-D cutaway diagram to illustrate all the goodies on the inside.

{ Andrew Batson | Continue reading }

asia, economics, food, drinks, restaurants |

October 26th, 2015

This article examines the extent to which advertising outside of an explicit campaign environment has the potential to benefit the electoral fortunes of incumbent politicians.

We make use of a novel case of non-campaign advertising, that of North Carolina Secretary of Labor Cherie Berry (R-NC), who has initiated the practice of having her picture and name displayed prominently on official inspection placards inside all North Carolina elevators. We […] find that Berry outperformed other statewide Republican candidates in the 2012 North Carolina elections. Our findings suggest that candidates can use this form of advertising to indirectly improve their electoral fortunes.

{ American Politics Research | Continue reading }

marketing |

October 23rd, 2015

Experts say fakes have become one of the most vexing problems in the art market. […]

Two years ago, the center, known for its work in bioengineering, encryption and nanotechnology, set about developing a way to infuse paintings, sculptures and other artworks with complex molecules of DNA created in the lab. […]

The new approach, in its formative stage, would implant synthetic DNA, not the personal DNA of the artists, because of privacy issues and because a person’s DNA could conceivably be stolen and embedded, thus undermining the authority of such a marking protocol.

The developers said the bioengineered DNA would be unique to each item and provide an encrypted link between the art and a database that would hold the consensus of authoritative information about the work. The DNA details could be read by a scanner available to anyone in the art industry wanting to verify an object.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

installation { Yayoi Kusama, The obliteration room, 2002-present }

art, genes, technology |

October 22nd, 2015

Statisticians love to develop multiple ways of testing the same thing. If I want to decide whether two groups of people have significantly different IQs, I can run a t-test or a rank sum test or a bootstrap or a regression. You can argue about which of these is most appropriate, but I basically think that if the effect is really statistically significant and large enough to matter, it should emerge regardless of which test you use, as long as the test is reasonable and your sample isn’t tiny. An effect that appears when you use a parametric test but not a nonparametric test is probably not worth writing home about.

A similar lesson applies, I think, to first dates. When you’re attracted to someone, you overanalyze everything you say, spend extra time trying to look attractive, etc. But if your mutual attraction is really statistically significant and large enough to matter, it should emerge regardless of the exact circumstances of a single evening. If the shirt you wear can fundamentally alter whether someone is attracted to you, you probably shouldn’t be life partners. […]

In statistical terms, a glance at across a bar doesn’t give you a lot of data and increases the probability you’ll make an incorrect decision. As a statistician, I prefer not to work with small datasets, and similarly, I’ve never liked romantic environments that give me very little data about a person. (Don’t get me started on Tinder. The only thing I can think when I see some stranger staring at me out of a phone is, “My errorbars are huge!” which makes it very hard to assess attraction.) […]

I think there’s even an argument for being deliberately unattractive to your date, on the grounds that if they still like you, they must really like you.

{ Obsession with Regression | Continue reading }

mathematics, relationships |

October 22nd, 2015

Neurotechnologies are “dual-use” tools, which means that in addition to being employed in medical problem-solving, they could also be applied (or misapplied) for military purposes.

The same brain-scanning machines meant to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease or autism could potentially read someone’s private thoughts. Computer systems attached to brain tissue that allow paralyzed patients to control robotic appendages with thought alone could also be used by a state to direct bionic soldiers or pilot aircraft. And devices designed to aid a deteriorating mind could alternatively be used to implant new memories, or to extinguish existing ones, in allies and enemies alike. […]

In 2005, a team of scientists announced that it had successfully read a human’s mind using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a technique that measures blood flow triggered by brain activity. A research subject, lying still in a full-body scanner, observed a small screen that projected simple visual stimuli—a random sequence of lines oriented in different directions, some vertical, some horizontal, and some diagonal. Each line’s orientation provoked a slightly different flurry of brain functions. Ultimately, just by looking at that activity, the researchers could determine what kind of line the subject was viewing.

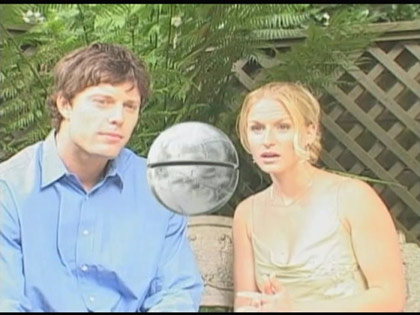

It took only six years for this brain-decoding technology to be spectacularly extended—with a touch of Silicon Valley flavor—in a series of experiments at the University of California, Berkeley. In a 2011 study, subjects were asked to watch Hollywood movie trailers inside an fMRI tube; researchers used data drawn from fluxing brain responses to build decoding algorithms unique to each subject. Then, they recorded neural activity as the subjects watched various new film scenes—for instance, a clip in which Steve Martin walks across a room. With each subject’s algorithm, the researchers were later able to reconstruct this very scene based on brain activity alone. The eerie results are not photo-

realistic, but impressionistic: a blurry Steve Martin floats across a surreal, shifting background.

Based on these outcomes, Thomas Naselaris, a neuroscientist at the Medical University of South Carolina and a coauthor of the 2011 study, says, “The potential to do something like mind reading is going to be available sooner rather than later.” More to the point, “It’s going to be possible within our lifetimes.”

{ Foreign Policy | Continue reading }

neurosciences |

October 20th, 2015

A recent Norwegian study shows that men and women react differently to various types of infidelity. Whereas men are most jealous of sexual infidelity, so-called emotional infidelity is what makes women the most jealous. Evolutionary psychology may help explain why this may be. […]

Men and women over thousands of generations have had to adapt to different challenges that are related to reproduction. Infidelity is one such challenge. A man must decide whether he really is the father of his partner’s child, and if he should choose to invest all his protection and status resources on this child. Since the dawn of time men have grappled with paternity insecurity, since fertilization occurs inside a woman’s body.

According to the evolutionary psychology explanation, men’s jealousy is an emotional reaction to signs of sexual infidelity. The jealousy serves to reduce the chances that his partner is cheating, since he then monitors her more closely.

It’s a different story for the child’s mother. She knows for sure that she is the child’s mother, but she must ensure that the child’s father will provide their offspring with food and the security and social status it needs. The greatest threat for the woman is not that the man has sex with other women, but that he spends time and resources on women other than her.

{ Medical Xpress | Continue reading }

evolution |

October 8th, 2015

Imagine that you are imprisoned in a tunnel that opens out onto a precipice two paces to your left, and a pit of vipers two paces to your right. To torment you, your evil captor forces you to take a series of steps to the left and right. You need to devise a series that will allow you to avoid the hazards — if you take a step to the right, for example, you’ll want your second step to be to the left, to avoid falling off the cliff. You might try alternating right and left steps, but here’s the catch: You have to list your planned steps ahead of time, and your captor might have you take every second step on your list (starting at the second step), or every third step (starting at the third), or some other skip-counting sequence. Is there a list of steps that will keep you alive, no matter what sequence your captor chooses?

In this brainteaser, devised by the mathematics popularizer James Grime, you can plan a list of 11 steps that protects you from death. But if you try to add a 12th step, you are doomed: Your captor will inevitably be able to find some skip-counting sequence that will plunge you over the cliff or into the viper pit.

Around 1932, Erdős asked, in essence, what if the precipice and pit of vipers are three paces away instead of two? What if they are N paces away? Can you escape death for an infinite number of steps? The answer, Erdős conjectured, was no — no matter how far away the precipice and viper pit are, you can’t elude them forever.

But for more than 80 years, mathematicians made no progress on proving Erdős’ discrepancy conjecture (so named because the distance from the center of the tunnel is known as the discrepancy).

{ Quanta | Continue reading }

mathematics |

October 5th, 2015

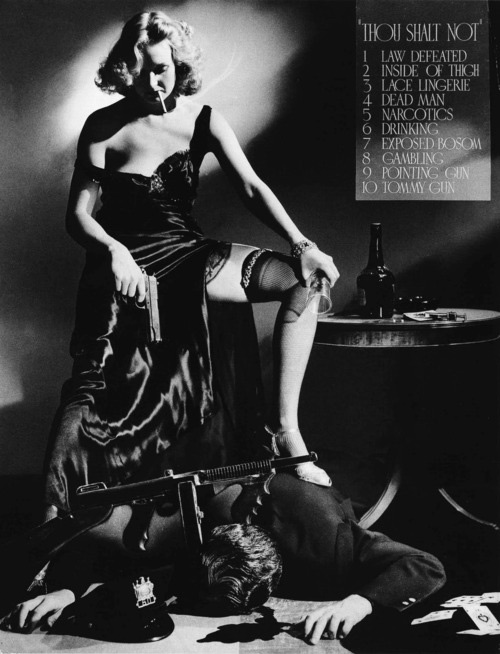

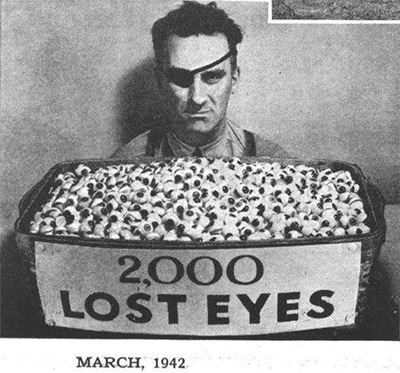

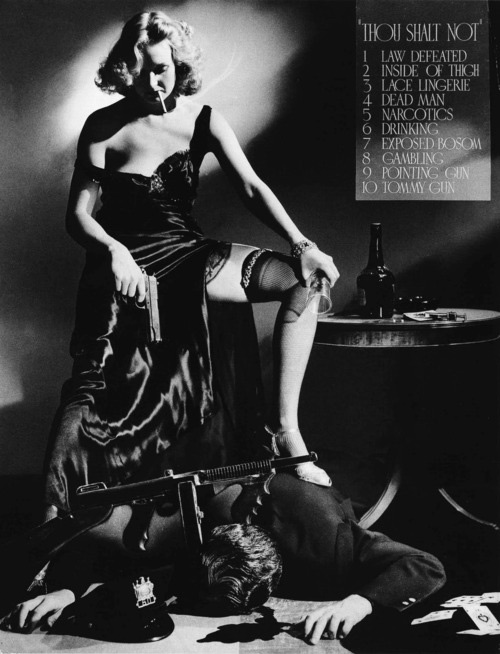

{ In 1934, the MPAA voluntarily passed the Motion Picture Production Code, more generally known as the Hays Code. The code prohibited certain plot lines and imagery from films and in publicity materials produced by the MPAA. Among other rules, there was to be no cleavage, no lace underthings, no drugs or drinking, no corpses, and no one shown getting away with a crime. A.L. Shafer, the head of photography at Columbia, took a photo that intentionally incorporated all of the 10 banned items into one image. | The Society Pages | Continue reading | More: Wikipedia }

flashback, showbiz |

October 5th, 2015

We review recent evidence revealing that the mere willingness to engage analytic reasoning as a means to override intuitive “gut feelings” is a meaningful predictor of key psychological outcomes in diverse areas of everyday life. For example, those with a more analytic thinking style are more skeptical about religious, paranormal, and conspiratorial concepts. In addition, analytic thinking relates to having less traditional moral values, making less emotional or disgust-based moral judgments, and being less cooperative and more rationally self-interested in social dilemmas. Analytic thinkers are even less likely to offload thinking to smartphone technology and may be more creative.

{ SSRN | Continue reading }

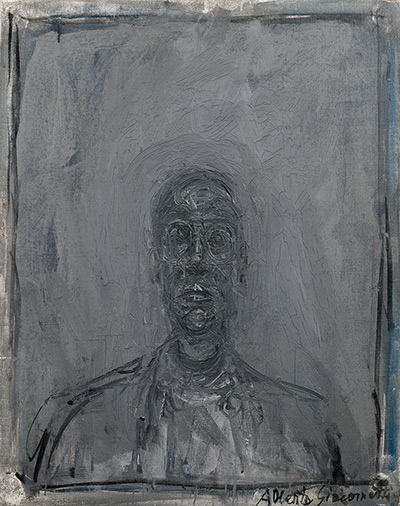

oil on canvas { Alberto Giacometti, Portrait of Pierre Josse, 1961 }

psychology |

October 2nd, 2015