Last week scientists at Harvard medical school reversed the ageing process in elderly mice. Please don’t get excited, unless you’re a mouse that is. The application to humans is a long way off and even if it will one day be possible, there are many issues attendant on a population that has the means to live forever. (…)

Medical intervention once seemed limited to curing us of diseases that kill. In my childhood, diphtheria and scarlet fever still carried people off, I had friends crippled by polio and aunts deformed by rickets. All this seemed the proper field for medical intervention.

We all know what happened next, a great swathe of advances in hygiene and medicine drove the major killers on to the back foot. From a combination of better lifestyle, cleaner cities and the benefits of a free health service, people began living longer.

We hear regularly of the latest treatments for coronary heart disease, breast cancer, kidney failure, and we live in the belief that when we have an unwelcome diagnosis the full force of medical knowledge will be marshalled for our benefit. We have come to expect better. Now we want life to go on forever. (…)

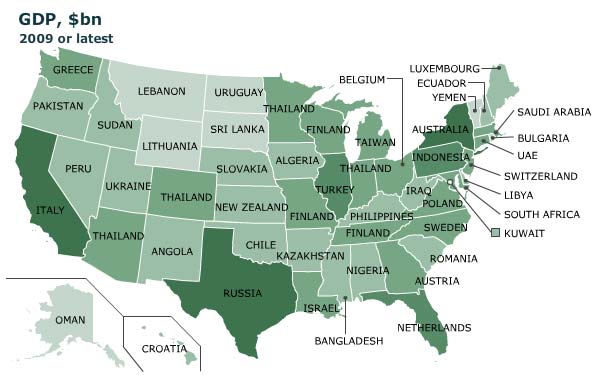

While most of us don’t want to live forever, many of us would enjoy living longer. At the same time we would like the planet to survive as we know it. There is a contradiction in contemplating a world where everyone lives much longer and where the planet’s resources are finite.

Unless we can learn to eat sand we should bear in mind the fates of places like Angkor Wat and Easter Island, places once dense with people and culture now empty ruins.

{ BBC | Continue reading }

Remember that billion heartbeat limit that seems to confine all mammals, from shrews to giraffes? It’s a pretty neat correlation, until you ponder the chief exception: Us.

Most mammals our size and weight are already fading away by age twenty or so, when humans are just hitting their stride. By eighty, we’ve had about three billion heartbeats! That’s quite a bonus.

How did we get so lucky?

Biologists figure that our evolving ancestors needed drastically extended lifespans, because humans came to rely on learning rather than instinct to create sophisticated, tool-using societies. That meant children needed a long time to develop. A mere two decades weren’t long enough for a man or woman to amass the knowledge needed for complex culture, let alone pass that wisdom on to new generations. (In fact, chimps and other apes share some of this lifespan bonus, getting about half as many extra heartbeats.)

So evolution rewarded those who found ways to slow the aging process. Almost any trick would have been enlisted, including all the chemical effects that researchers have recently stimulated in mice, through caloric restriction. In other words, we’ve probably already incorporated all the easy stuff! We’re the mammalian Methuselahs and little more will be achieved by asceticism or other drastic life-style adjustments. Good diet and exercise will help you get your eighty years. But to gain a whole lot more lifespan, we’re going to have to get technical.

So what about intervention and repair?

Are your organs failing? Grow new ones, using a culture of your own cells!

Are your arteries clogged? Send tiny nano-robots coursing through your bloodstream, scouring away plaque! Use tuned masers to break the excess intercell linkages that make flesh less flexible over time.

Install little chemical factories to synthesize and secrete the chemicals that your own glands no longer adequately produce. Brace brittle bones with ceramic coatings, stronger than the real thing!

In fact, we are already doing many of these things, in early-primitive versions. So there is no argument over whether such techniques will appear in coming decades, only how far they will take us.

Might enough breakthroughs coalesce at the same time to let us routinely offer everybody triple-digit spans of vigorous health? Or will these complicated interventions only add more digits to the cost of medical care, while struggling vainly against the same age-barrier in a frustrating war of diminishing returns?

I’m sure it will seem that way for the first few decades of the next century… until, perhaps, everything comes together in a rush.

If that happens — if we suddenly find ourselves able to fix old age — there will surely be countless unforeseen consequences… and one outcome that’s absolutely predictable: We’ll start taking that miracle for granted, too.

On the other hand, it may not work as planned. Many scientists suggest that attempts at intervention and repair will ultimately prove futile, because senescence and death are integral parts of our genetic nature. (…)

So far, our sole hope for such a voyage to the far-off future — and a slim one, at that — is something called cryonics, the practice of freezing a terminal patient’s body, after he or she has been declared legally dead. Some of those who sign up for this service take the cheap route of having only their heads prepared and stored in liquid nitrogen, under the assumption that folks in the Thirtieth Century will simply grow fresh bodies on demand. Their logic is expressed with chilling rationality. “The real essence of who I am is the software contained in my brain. My old body — the hardware — is just meat.” (…)

According to some techno-transcendentalists, “growing new bodies” will seem like child’s play in the future. (..)

All right, what if one of them finally works? All too often, we find that solving one problem only leads to others, sometimes even more vexing.

A number of eminent writers like Robert Heinlein, Greg Bear, Kim Stanley Robinson and Gregory Benford have speculated on possible consequences, should Mister G. Reaper ever be forced to hang up his scythe and seek other employment. For example, if the Death Barrier comes crashing down, will we be able to keep shoehorning new humans into a world already crowded with earlier generations? Or else, as envisioned by author John Varley, might such a breakthrough demand draconian population-control measures, limiting each person to one direct heir per lifespan?

{ David Brin | Continue reading }

I think we have a 50% chance of achieving medicine capable of getting people to 200 in the decade 2030-2040. Presuming we do indeed do that, the actual achievement of 200 will probably be in the decade 2140-2150 - it will be someone who was about 85-90 at the time that the relevant therapies were developed.

There will be no one technological breakthrough that achieves this. It will be achieved by a combination of regenerative therapies that repair all the different molecular and cellular degenerative components of aging.

{ When Will Life Expectancy Reach 200 Years? Aubrey de Grey and David Brin Disagree in Interview }

To see how far back the immortality fantasy goes, read about Gilgamesh, or the Chinese First Emperor who drank mercury in order to live forever — and died in his forties.

{ David Brin/IEET | Continue reading }

Let’s say you transfer your mind into a computer—not all at once but gradually…

{ Carl Zimmer/Scientific American | Continue reading }