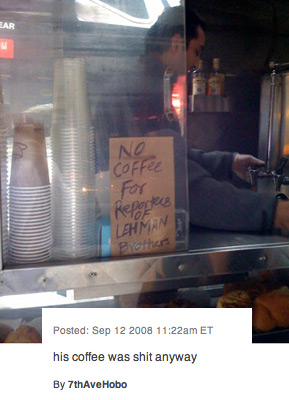

Coffee is under threat from climate change, according to a study which found that popular Arabica beans could face extinction within decades.

Rising global temperatures and subtle changes in seasonal conditions could make 99.7 per cent of Arabica-growing areas unsuitable for the plant by 2080. […]

Identifying new sites where arabica could be grown away from its natural home in the mountains of Ethiopia and South Sudan could be the only way of preventing the demise of the species, researchers said.

{ Telegraph | Continue reading }

unrelated {List of unsolved problems }

climate, food, drinks, restaurants |

November 10th, 2012

{ My Bloody Valentine have announced a headlining slot at Japan’s Tokyo Rocks festival in May 2013, where they will be playing exclusive material from a brand new album. The album, the very-long-awaited follow-up to 1991’s classic ‘Loveless’, has been 21 years in the making. | NME }

music |

November 8th, 2012

marketing |

November 7th, 2012

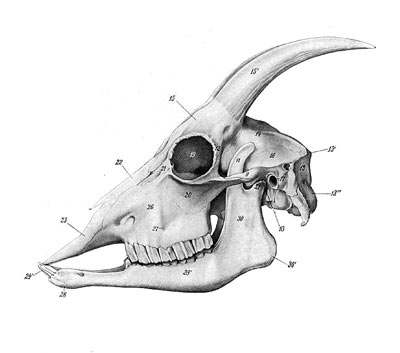

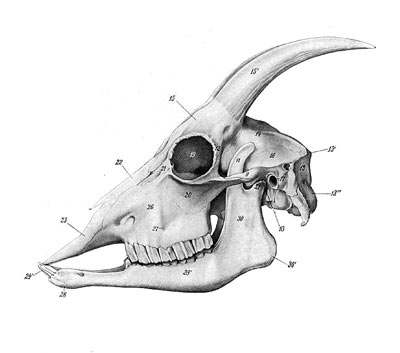

Michael McAlpine’s shiny circuit doesn’t look like something you would stick in your mouth. It’s dashed with gold, has a coiled antenna and is glued to a stiff rectangle. But the antenna flexes, and the rectangle is actually silk, its stiffness melting away under water. And if you paste the device on your tooth, it could keep you healthy.

The electronic gizmo is designed to detect dangerous bacteria and send out warning signals, alerting its bearer to microbes slipping past the lips. Recently, McAlpine, of Princeton University, and his colleagues spotted a single E. coli bacterium skittering across the surface of the gadget’s sensor. The sensor also picked out ulcer-causing H. pylori amid the molecular medley of human saliva, the team reported earlier this year in Nature Communications.

At about the size of a standard postage stamp, the dental device is still too big to fit comfortably in a human mouth. “We had to use a cow tooth,” McAlpine says, describing test experiments. But his team plans to shrink the gadget so it can nestle against human enamel. McAlpine is convinced that one day, perhaps five to 10 years from now, everyone will wear some sort of electronic device. “It’s not just teeth,” he says. “People are going to be bionic.”

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

future, health, technology |

November 7th, 2012

Many children spontaneously report memories of ‘past lives’. For believers, this is evidence for reincarnation; for others, it’s a psychological oddity. But what happens when they grow up?

Icelandic psychologists Haraldsson and Abu-Izzedin looked into it. They took 28 adults, members of the Druze community of Lebanon. They’d all been interviewed about past life memories by the famous reincarnationist Professor Ian Stephenson in the 70s, back when they were just 3-9 years old. Did they still ‘remember’? […]

As children they reported on average 30 distinct memories of past lives. As adults they could only remember 8, but of those, only half matched the ones they’d talked about previously.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

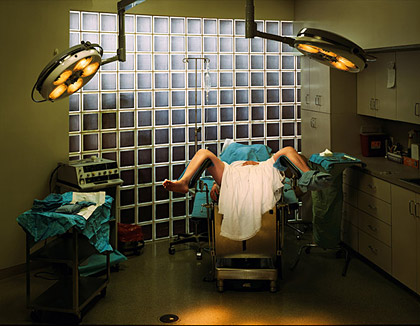

photo { Taryn Simon }

kids, memory |

November 7th, 2012

Specialty stores do not have to compete with supermarket prices to increase sales, according to a recent study from the University at Buffalo School of Management.

Researchers found that consumers are not concerned about higher prices when shopping at specialty stores, and that they are more likely to buy items related to their main purchase than at a supermarket.

In addition, specialty stores’ customers are more apt to respond to holiday promotions than to sale prices.

{ University at Buffalo | Continue reading }

economics |

November 7th, 2012

Brains are very costly. Right now, just sitting here, my brain (even though I’m not doing much other than talking) is consuming about 20- 25 percent of my resting metabolic rate. That’s an enormous amount of energy, and to pay for that, I need to eat quite a lot of calories a day, maybe about 600 calories a day, which back in the Paleolithic was quite a difficult amount of energy to acquire. So having a brain of 1,400 cubic centimeters, about the size of my brain, is a fairly recent event and very costly.

The idea then is at what point did our brains become so important that we got the idea that brain size and intelligence really mattered more than our bodies? I contend that the answer was never, and certainly not until the Industrial Revolution.

Why did brains get so big? There are a number of obvious reasons. One of them, of course, is for culture and for cooperation and language and various other means by which we can interact with each other, and certainly those are enormous advantages. If you think about other early humans like Neanderthals, their brains are as large or even larger than the typical brain size of human beings today. Surely those brains are so costly that there would have had to be a strong benefit to outweigh the costs. So cognition and intelligence and language and all of those important tasks that we do must have been very important.

We mustn’t forget that those individuals were also hunter-gatherers. They worked extremely hard every day to get a living. A typical hunter-gatherer has to walk between nine and 15 kilometers a day. A typical female might walk 9 kilometers a day, a typical male hunter-gatherer might walk 15 kilometers a day, and that’s every single day. That’s day-in, day-out, there’s no weekend, there’s no retirement, and you do that for your whole life. It’s about the distance if you walk from Washington, DC to LA every year. That’s how much walking hunter-gatherers did every single year.

{ Daniel Lieberman/Edge | Continue reading }

brain, flashback, science |

November 6th, 2012

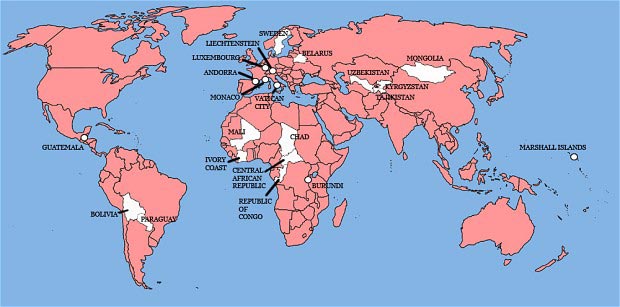

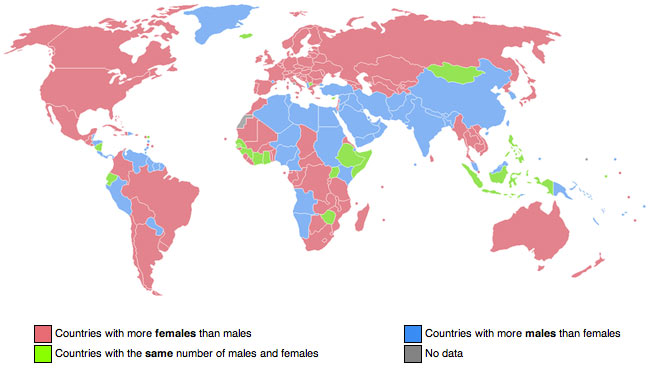

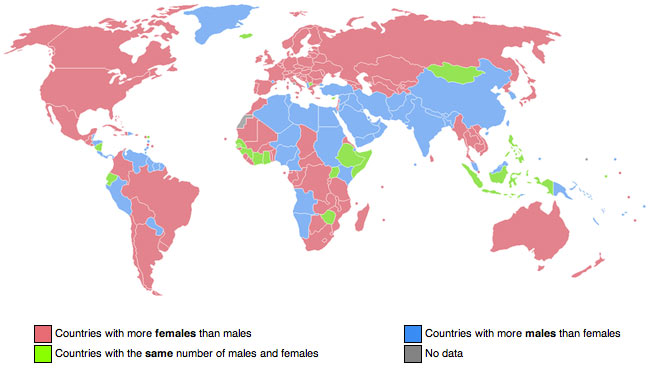

{ In humans the secondary sex ratio (i.e., at birth) is commonly assumed to be 105 boys to 100 girls, an assumption that is a subject of debate in the scientific community. The sex ratio for the entire world population is 101 males to 100 females. | Wikipedia | Continue reading }

genders |

November 6th, 2012

Once in our history, the world-wide population of human beings skidded so sharply we were down to roughly a thousand reproductive adults. One study says we hit as low as 40. […] around 70,000 B.C., a volcano called Toba, on Sumatra, in Indonesia went off, blowing roughly 650 miles of vaporized rock into the air. It is the largest volcanic eruption we know of, dwarfing everything else… […] With so much ash, dust and vapor in the air, Sam Kean says it’s a safe guess that Toba “dimmed the sun for six years, disrupted seasonal rains, choked off streams and scattered whole cubic miles of hot ash (imagine wading through a giant ashtray) across acres and acres of plants.” Berries, fruits, trees, African game became scarce; early humans, living in East Africa just across the Indian Ocean from Mount Toba, probably starved, or at least, he says, “It’s not hard to imagine the population plummeting.”

Then — and this is more a conjectural, based on arguable evidence — an already cool Earth got colder. The world was having an ice age 70,000 years ago, and all that dust hanging in the atmosphere may have bounced warming sunshine back into space. So we almost vanished. […]

It took almost 200,000 years to reach our first billion (that was in 1804), but now we’re on a fantastic growth spurt, to 3 billion by 1960, another billion almost every 13 years since then.

{ NPR | Continue reading }

elements, flashback |

November 6th, 2012

The Mariana Trench is the deepest part of the world’s oceans. It is located in the western Pacific Ocean, to the east of the Mariana Islands.

The trench reaches a maximum-known depth of 10.994 km or 6.831 mi at the Challenger Deep, a small slot-shaped valley in its floor, at its southern end, although some unrepeated measurements place the deepest portion at 11.03 kilometres (6.85 mi).

The trench is not the part of the seafloor closest to the center of the Earth. This is because the Earth is not a perfect sphere: its radius is about 25 kilometres (16 mi) less at the poles than at the equator. As a result, parts of the Arctic Ocean seabed are at least 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) closer to the Earth’s center than the Challenger Deep seafloor.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

related { What if you exploded a nuclear bomb at the bottom of the Marianas Trench? }

science, water |

November 6th, 2012

James Joyce |

November 6th, 2012

The eminent criminal psychologist and creator of the widely used Psychopathy Checklist paused before answering. “I think, in general, yes, society is becoming more psychopathic,” he said. “I mean, there’s stuff going on nowadays that we wouldn’t have seen 20, even 10 years ago. Kids are becoming anesthetized to normal sexual behavior by early exposure to pornography on the Internet. Rent-a-friend sites are getting more popular on the Web, because folks are either too busy or too techy to make real ones. … The recent hike in female criminality is particularly revealing. And don’t even get me started on Wall Street.”

{ The Chronicle of Higher Education | Continue reading }

psychology |

November 6th, 2012

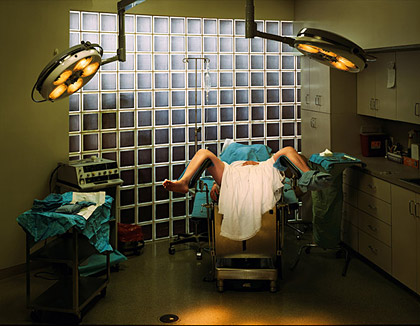

Cotard’s Syndrome is the delusional belief that one is dead or missing internal organs or other body parts. Those who suffer from this “delusion of negation” deny their own existence. The eponymous French neurologist Jules Cotard called it le délire de négation (”negation delirium”). […]

In a review of 100 cases, Berrios and Luque (1995) found that: “Depression was reported in 89% of subjects; the most common nihilistic delusions concerned the body (86%) and existence (69%).”

{ The Neurocritic | Continue reading }

image { Chris Scarborough }

psychology |

November 6th, 2012

For more than 60 years, Robert Martensen’s lung cells replicated without a hitch, regulated by specialized enzymes called kinases. Much like thermostats that adjust the temperature in a room to make sure it’s not too hot or too cold, kinases make sure that the right number of new cells are created as old ones die. But sometime in his early sixties, something changed inside Martensen. One or more of the genes coding for his kinases mutated, causing his lung cells to begin replicating out of control.

At first the clusters of rogue cells were so small that Martensen had no idea they existed. Nor was anyone looking for them inside the lean, ruddy-faced physician, who exercised most days and was an energetic presence as the chief historian at the National Institutes of Health. Then came a day in February 2011 when Martensen noticed a telltale node in his neck while taking a shower. “I felt no pain,” he recalls, “but I knew what it was. I told myself in the shower that this was cancer—and that from that moment on, my life would be different.”

Martensen initially thought it was lymphoma, cancer of the lymph glands, which has a higher survival rate than many other cancers. But after a biopsy, he was stunned to discover he had late-stage lung cancer, a disease that kills 85 percent of patients within a year. Most survive just a few months. […]

He heard about a new drug being tested at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Developed by pharmaceutical giant Pfizer, the drug had dramatically reduced lung cancer tumors and prolonged life in the couple hundred patients who had so far used it, with few side effects. But there was a catch. The new med, called Xalkori, worked for only 3 to 5 percent of all lung cancer patients.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

photo { Patrick Romero }

genes, health, science |

November 6th, 2012

The romantic view of romance in Western culture says a very small fraction of people would make a great partner for you, customarily one.

Some clues suggest that in fact quite a large fraction of people would make a suitable spouse for a given person. Arranged marriages apparently go pretty well rather than terribly. […]

It seems we overstate the rarity of good matches. Why would we do that? One motive would be to look like you have high standards, which suggests that you are good enough yourself to support such standards. But does this really make sense? In practice, most of the ways a person could be especially unusual such that it is hard for them to find a suitable mate are not in the direction of greatness. Most of them are just in various arbitrary directions of weirdness.

{ Overcoming Bias | Continue reading }

relationships |

November 5th, 2012

Research shows that friends influence how girls and women view and judge their own body weight, shape and size. What Wasylkiw and Williamson’s work sheds light on, is how much of a young woman’s body concerns are shaped by her perceptions of peers’ concerns with their own body versus her peers’ actual body concerns. […]

They found that the more women felt under pressure to be thin, the more likely they were to have body image concerns, irrespective of their actual weight and shape. Interestingly, body talk between friends that focussed on exercise was related to lower body dissatisfaction.

{ Springer | Continue reading }

health, psychology |

November 5th, 2012

Rats use a sense that humans don’t: whisking. They move their facial whiskers back and forth about eight times a second to locate objects in their environment. Could humans acquire this sense? And if they can, what could understanding the process of adapting to new sensory input tell us about how humans normally sense? At the Weizmann Institute, researchers explored these questions by attaching plastic “whiskers” to the fingers of blindfolded volunteers and asking them to carry out a location task. The findings, which recently appeared in the Journal of Neuroscience, have yielded new insight into the process of sensing, and they may point to new avenues in developing aids for the blind.

{ Weizmann Institute of Science | Continue reading }

science |

November 5th, 2012

In quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle is any of a variety of mathematical inequalities asserting a fundamental limit to the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties of a particle, such as position x and momentum p, can be known simultaneously. The more precisely the position of some particle is determined, the less precisely its momentum can be known, and vice versa. The original heuristic argument that such a limit should exist was given by Werner Heisenberg in 1927, after whom it is sometimes named, as the Heisenberg principle. […]

Historically, the uncertainty principle has been confused with a somewhat similar effect in physics, called the observer effect, which notes that measurements of certain systems cannot be made without affecting the systems.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

photo { Jason Lazarus }

ideas, photogs, science |

November 5th, 2012