A fundamental difficulty in artificial intelligence is that nobody really knows what intelligence is, especially for systems with senses, environments, motivations and cognitive capacities which are very different to our own.

Although there is no strict consensus among experts over the definition of intelligence for humans, most definitions share many key features. In all cases, intelligence is a property of an entity, which we will call the agent, that interacts with an external problem or situation, which we will call the environment. An agent’s intelligence is typically related to its ability to succeed with respect to one or more objectives, which we will call the goal. The emphasis on learning, adaptation and flexibility common to many definitions implies that the environment is not fully known to the agent. Thus true intelligence requires the ability to deal with a wide range of possibilities, not just a few specific situations. Putting these things together gives us our informal definition: Intelligence measures an agent’s general ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments. We are confident that this definition captures the essence of many common perspectives on intelligence. It also describes what we would like to achieve in machines: A very general capacity to adapt and perform well in a wide range of situations.

{ Shane Legg and Marcus Hutter | Continue reading | PDF }

Artificial general intelligence (AGI) refers to research aimed at tackling the full problem of artificial intelligence, that is, create truly intelligent agents. This sets it apart from most AI research which aims at solving relatively narrow domains, such as character recognition, motion planning, or increasing player satisfaction in games. But how do we know when an agent is truly intelligent? A common point of reference in the AGI community is Legg and Hutter’s formal definition of universal intelligence, which has the appeal of simplicity and generality but is unfortunately incomputable. (…)

Intelligence is one of those interesting concepts that everyone has an opinion about, but few people are able to give a definition for – and when they do, their definitions tend to disagree with each other. And curiously, the consensus opinions change over time: consider for example a number of indicators for human intelligence like arithmetic skills, memory capacity, chess playing, theorem proving – all of which were commonly employed in the past, but since machines now outperform humans on those tasks, they have fallen into disuse. We refer the interested reader to a comprehensive treatment of the subject matter in Legg (2008).

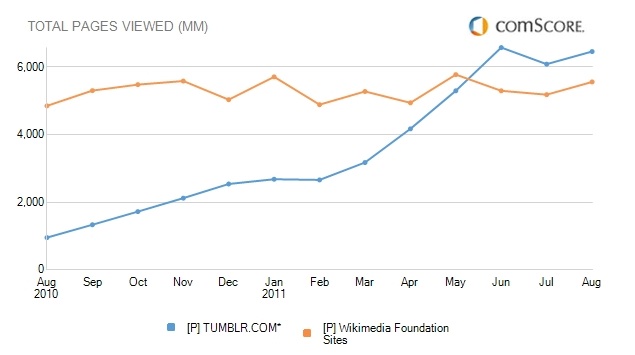

The current artificial intelligence literature features a panoply of benchmarks, many of which, unfortunately, are very narrow, applicable only on a small class of tasks. This is not to say that they cannot be useful for advancing the field, but in retrospect it often becomes clear how little an advance on a narrow task contributed to the general field. For example, researchers used to argue that serious progress on a game as complex as chess would necessarily generate many insights, and the techniques employed in the solution would be useful for real-world problems – well, no. (…)

Legg and Hutter propose their definition as a basis for any test of artificial general intelligence. Among the advantages they list are its wide range of applicability (from random to super-human), its objectivity, its universality, and the fact that it is formally defined.

Unfortunately however, it suffers from two major limitations: a) Incomputability: Universal intelligence is incomputable, because the Kolmogorov complexity is incomputable for any environment (due to the halting problem). b) Unlimited resources: The authors deliberately do not include any consideration of time or space resources in their definition. This means that two agents that act identically in theory will be assigned the exact same intelligence Υ, even if one of them requires infinitely more computational resources to choose its action (i.e. would never get to do any action in practice) than the other.

{ Tom Schaul, Julian Togelius, Jürgen Schmidhuber, Measuring Intelligence through Games, 2011 | Continue reading | PDF }