‘If you want to succeed in your life, remember this phrase: The past does not equal the future. Because you failed yesterday; or all day today; or a moment ago; or for the last six months; the last sixteen years; or the last fifty years of life, doesn’t mean anything… All that matters is: What are you going to do, right now? –Anthony Robbins

Life is not a long slow decline from sunlit uplands towards the valley of death. It is, rather, a U-bend.

When people start out on adult life, they are, on average, pretty cheerful. Things go downhill from youth to middle age until they reach a nadir commonly known as the mid-life crisis. So far, so familiar. The surprising part happens after that. Although as people move towards old age they lose things they treasure—vitality, mental sharpness and looks—they also gain what people spend their lives pursuing: happiness.

This curious finding has emerged from a new branch of economics that seeks a more satisfactory measure than money of human well-being. Conventional economics uses money as a proxy for utility—the dismal way in which the discipline talks about happiness. But some economists, unconvinced that there is a direct relationship between money and well-being, have decided to go to the nub of the matter and measure happiness itself.

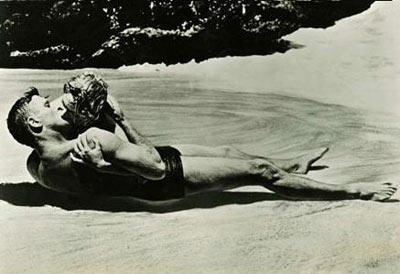

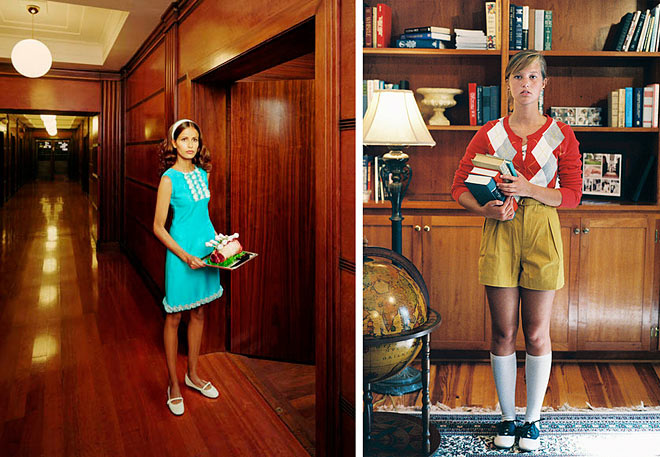

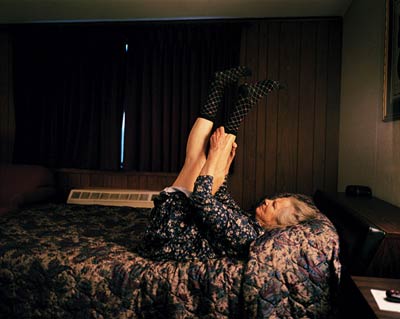

photo { The Haven of Contentment }