science

At Çatalhöyük in Turkey, it appears that people did not live in families. Instead, the society seems to have been organised completely differently.

Discovered in 1958, Çatalhöyük’s many buildings are built so close together that people had to get in through the roof. Its inhabitants farmed crops and domesticated animals, and experimented with painting and sculpture.

They also buried their dead beneath the floors of the houses, suggesting that people were buried where they lived. So Marin Pilloud of the Central Identification Laboratory in Hickam, Hawaii, realised she could work out who lived together. (…)

We are used to the idea that living in close contact with our relatives helps to promote our own genetic inheritance and keep hold of our money and possessions over the generations. So why should Stone Age populations be different?

Pilloud thinks Çatalhöyük developed its odd social structure as the people began settling down and farming, rather than hunting and gathering. “It makes a lot of sense to shift to a community-centred society with the adoption of agriculture,” she says. People living in close quarters all year round and working together to produce food needed to create a strong community, rather than only cooperating with relatives.

{ NewScientist | Continue reading }

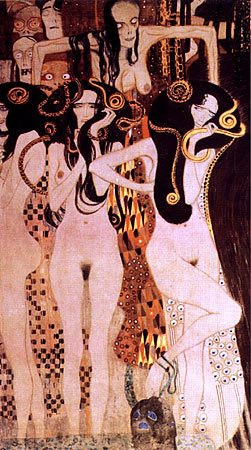

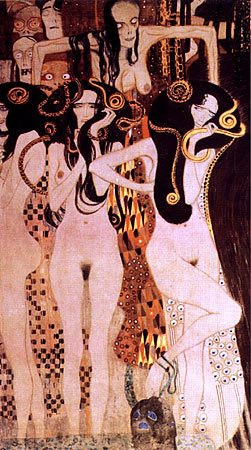

painting { Gustav Klimt, Beethoven Frieze, Hostile Force (detail), 1902 }

flashback, relationships, science | July 8th, 2011 9:14 am

Last year, a team of NASA-funded scientists claimed to have found bacteria that could use arsenic to build their DNA, making them unlike any form of life known on Earth. That didn’t go over so well. One unfortunate side-effect of the hullabaloo over arsenic life was that people were distracted from all the other research that’s going on these days into weird biochemistry. Derek Lowe, a pharmaceutical chemist who writes the excellent blog In the Pipeline, draws our attention today to one such experiment, in which E. coli is evolving into a chlorine-based form of life.

Scientists have been contorting E. coli in all sorts of ways for years now to figure out what the limits of life are. Some researchers have rewritten its genetic code, for example, so that its DNA can encode proteins that include amino acids that are not used by any known organism.

Others have been tinkering with the DNA itself. In all living things, DNA is naturally composed of four compounds, adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine. Thymine is a ring of carbon and nitrogen atoms, with oxygen and hydrogens atoms dangling off the sides. Since the 1970s, some scientists have tried to swap thymine for other molecules. This compound is called 5-chlorouracil, the “chloro-” referring to the chlorine marked here in red. No natural DNA contains chlorine.

{ Carl Zimmer/Discover | Continue reading }

related { The end of E. Coli }

genes, science | July 8th, 2011 9:05 am

A gentle touch on the arm can be surprisingly persuasive. Consider these research findings. Library users who are touched while registering, rate the library and its personnel more favourably than the non-touched; diners are more satisfied and give larger tips when waiting staff touch them casually; people touched by a stranger are more willing to perform a mundane favour; and women touched by a man on the arm are more willing to share their phone number or agree to a dance.

Why should this be? Up until now research in this area has been exclusively behavioural: these effects have been observed, but we don’t really know why. Now a study has made a start at understanding the neuroscience of how touch exerts its psychological effects. (…)

The most important finding is that a touch on the arm enhanced the brain’s response to emotional pictures.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

neurosciences, relationships | July 6th, 2011 6:55 pm

Whines, cries, and motherese have important features in common: they are all well-suited for getting the attention of listeners, and they share salient acoustic characteristics – those of increased pitch, varied pitch contours, and slowed production, though the production speed of cries varies. Motherese is the child-directed speech parents use towards infants and young children to sooth, attract attention, encourage particular behaviors, and prohibit the child from dangerous acts. Infant cries are the sole means of communication for infants for the first few months, and a primary means in the later months. Cries signal that the infant needs care, be it feeding, changing, protection, or physical contact. Whines enter into a child’s vocal repertoire with the onset of language, typically peaking between 2.5 and 4 years of age. This sound is perceived as more annoying even than infant cries.

These three attachment vocalizations – whines, cries, and motherese – each have a particular effect on the listener; to bring the attachment partner nearer. (…)

Participants, regardless of gender or parental status, were more distracted by whines than machine noise or motherese as measured by proportion scores. In absolute numbers, participants were most distracted by whines, followed by infant cries and motherese.

{ Whines, cries, and motherese: Their relative power to distract | Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology | Continue reading }

photo { Tod Seelie }

kids, noise and signals, relationships, science | July 6th, 2011 6:44 pm

Among ethical concepts, conscience is a remarkable survivor. During the 2000 years of its existence it has had ups and downs, but has never gone away. Originating as Roman conscientia, it was adopted by the Catholic Church, redefined and competitively claimed by Luther and the Protestants during the Reformation, adapted to secular philosophy during the Enlightenment, and is still actively abroad in the world today. Yet the last few decades have been cloudy ones for conscience, a unique time of trial.

The problem for conscience has always been its precarious authorization. It is both a uniquely personal impulse and a matter of institutional consensus, a strongly felt personal view and a shared norm upon which all reasonable or ethical people are expected to agree. As a result of its mixed mandate, conscience performs in differing and even contradictory ways.

{ Paul Strohm/OUP | Continue reading }

related { Can data determine moral values? }

photo { Uri Korn }

ideas, photogs, psychology | July 6th, 2011 6:35 pm

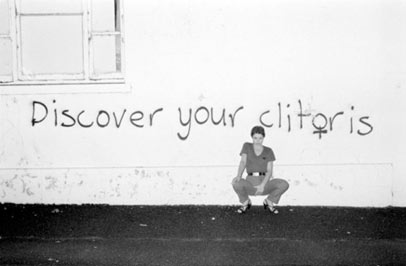

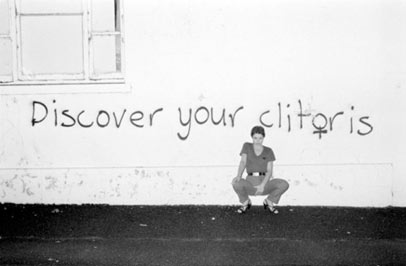

Female sexuality is particularly enigmatic, simply because the sex function in women is so much more complex than that of their male counterparts. A study conducted by Dutch scientist Gert Holstege showed that while the areas in male brains activated during orgasm were not surprising, the activated areas in the female brains were slightly different. For one, the female brain becomes noticeably silent in certain areas, like in the lateral orbitofrontal cortex and the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, two areas in the brain that process feelings and thoughts associated with self-control and social judgement. Holstege noted that “at the moment of orgasm, women do not have any emotional feelings.” (…)

Even women in good health have a difficult time achieving climax. Reportedly, 10% of women have never had an orgasm, and as many as 50% of women have trouble being aroused.

{ BrainBlogger | Continue reading }

neurosciences, relationships, sex-oriented | July 5th, 2011 3:40 pm

Imagine you are a single, heterosexual woman. You meet a nice man at the driving range, or on a blind date. You like him and he likes you. You date, you get engaged, you get married. You decide to have a child together, so you go off the pill. One morning you wake up and look at your husband, and it’s like seeing him through new eyes. Who is this stranger you married, and what did you ever see in him?

After some articles made the news when they suggested mate preferences change on hormonal contraception, this seemed to be the scenario in the heads of many women. Is my pill deceiving me? What if my birth control is making me date the wrong man?

Several articles over the years have demonstrated that women prefer men with more masculine features at midcycle, or ovulation, and more feminine features in less fertile periods. Based on body odor, women and men also often prefer individuals with MHC (major histocompatibility complex) that are different from theirs, which may be a way for them to select mates that will give their offspring an immunological advantage. These findings have been replicated a few times, looking at a few different gendered traits. And as I suggested above, other work has suggested that the birth control pill, which in some ways mimics pregnancy, may mask our natural tendency to make these distinctions and preferences, regarding both masculinity and MHC.

{ Context and Variation | Continue reading }

image { Thanks Glenn! }

neurosciences, relationships, science | July 5th, 2011 3:33 pm

{ There are about 2,000 species of fireflies, a type of beetle that lights up its abdomen with a chemical reaction to attract a mate. That glow can be yellow, green or pale-red. In some places the firefly dance is synchronized, with the insects flashing in unison or in waves. The lightshow has also been beneficial to science—researchers have found that the chemical responsible for it, luciferase, is a useful marker in a variety of applications, including genetic engineering and forensics. | Smithsonian magazine | full article }

insects, science | July 1st, 2011 8:00 pm

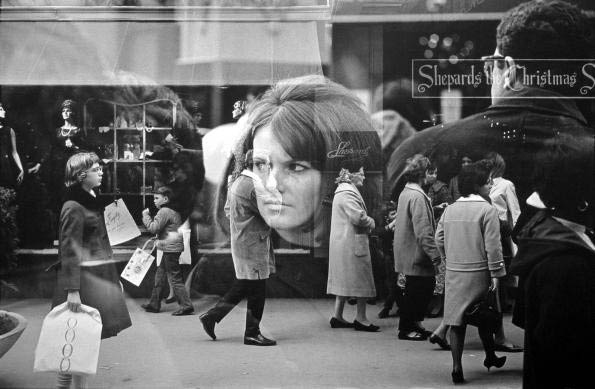

First impressions are important, and they usually contain a healthy dose both of accuracy and misperception. But do people know when their first impressions are correct? They do reasonably well, according to a recent study.

Sometimes after meeting a person for the first time, there is a strong sense that you really understand him or her—you immediately feel as if you could predict his or her behavior in a variety of situations, and you feel that even your first impression would agree with those of others who know that person well. That is, your impression feels realistically accurate (Funder, 1995, 1999). Other times, you leave an interaction feeling somewhat unsure about how accurate your impression is—it is not clear how that individual would behave in different situations or what his or her close friends and family members would say about him or her. Are such intuitions about the realistic accuracy of one’s impressions valid? That is, do people know when they know? The current studies address this question by examining the extent to which people have accuracy awareness—an understanding of whether their first impressions of others’ personalities are realistically accurate.

{ Social Psychological and Personality Science | Continue reading }

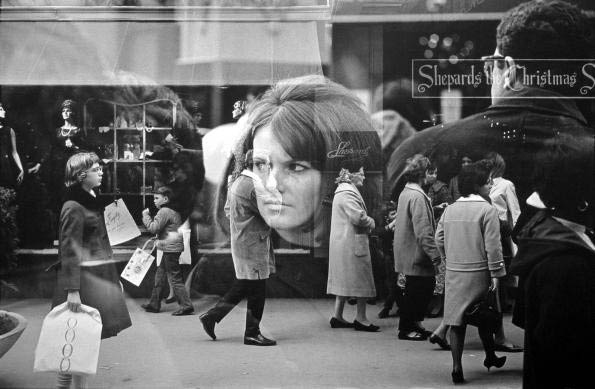

photo { Harry Callahan }

psychology, relationships | July 1st, 2011 4:45 pm

Each culture has its agreed-upon list of taboo words and it doesn’t matter how many times these words are repeated, they still seem to retain their power to shock. Scan a human brain, swear at it, and you’ll see its emotional centres jangle away.

Recent research has shown that this emotional impact can have an analgesic effect, and there’s other evidence that strategically deployed swear words can make a speech more memorable. But it’s not all positive. A new study suggests that swear words have a dark side. Megan Robbins and her team recorded snippets of speech from middle-aged women with rheumatoid arthritis, and others with breast cancer, and found those who swore more in the company of other people also experienced increased depression and a perceived loss of social support.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

photo { Calvin Sawer }

Linguistics, health, psychology | July 1st, 2011 4:25 pm

One way to study a network is to break it down into its simplest pattern of links. These simple patterns are called motifs and their numbers usually depend on the type of network.

One of the big puzzles of network science is that some motifs crop up much more often than others. These motifs are clearly important. Remove them (or change their distribution) and the behaviour of the network changes too. But nobody knows why.

Today, Xiao-Ke Xu at Hong Kong Polytechnic University and friends say they know why and the answer is intimately linked to the existence of rich clubs within a network.

Let’s step back for a bit of background. In many networks, a small number of nodes are well connected to large number of others. The group of all well-connected nodes is known as the “rich club” and it is known to play an important role in the network of which it is part.

Rich clubs are particularly influential in a specific class of network in which the number of links between nodes varies in a way that is scale free (ie follows a power law).

This is an important class. It includes the internet, social networks, airline networks and many naturally occurring networks such as gene regulatory networks.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

photo { Jimi Franklin }

ideas, science, technology | July 1st, 2011 4:22 pm

On 26 September 1991, eight “bionauts,” as they called themselves, wearing identical red Star Trek–like jumpsuits (made for them by Marilyn Monroe’s former dressmaker) waved to the assembled crowd and climbed through an airlock door in the Arizona desert. They shut it behind them and opened another that led into a series of hermetically sealed greenhouses in which they would live for the next two years. The three-acre complex of interconnected glass Mesoamerican pyramids, geodesic domes, and vaulted structures contained a tropical rain forest, a grassland savannah, a mangrove wetland, a farm, and a salt-water ocean with a wave machine and gravelly beach. This was Biosphere 2—the first biosphere being Earth—a $150 million experiment designed to see if, in a climate of nuclear and ecological fear, the colonization of space might be possible.

{ Cabinet | Continue reading }

artwork { Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Duel after the Masquerade, 1857 }

flashback, science | July 1st, 2011 4:06 pm

The wrinkles that develop on wet fingers could be an adaptation to give us better grip in slippery conditions, the latest theory suggests.

The hypothesis, from Mark Changizi, an evolutionary neurobiologist at 2AI Labs in Boise, Idaho, and his colleagues goes against the common belief that fingers turn prune-like simply because they absorb water.

Changizi thinks that the wrinkles act like rain treads on tyres. They create channels that allow water to drain away as we press our fingertips on to wet surfaces. This allows the fingers to make greater contact with a wet surface, giving them a better grip.

{ Nature | Continue reading }

science | July 1st, 2011 3:32 pm

For a long time, the mechanisms of taste seemed relatively straightforward. (…) Ever since Democritus hypothesized in the fourth century B.C. that the sensation of taste was an effect of the shape of food particles, the tongue has been seen as a simple sensory organ. (…) Plato believed Democritus. (…) Aristotle believed Plato. In De Anima, the four primary tastes Aristotle described were the already classic sweet, sour, salty, and bitter.

Over the ensuing millennium, this ancient theory remained largely unquestioned. The tongue was seen as a mechanical sensor, in which the qualities of foods were impressed upon its papillaed surface. The discovery of taste buds in the 19th century gave new credence to this theory. Under a microscope, these cells looked like little keyholes into which our chewed food might fit, thus triggering a taste sensation. By the start of the 20th century, scientists were beginning to map the tongue, consigning each of our four flavors to a specific area. The tip of our tongue loved sweet things, while the sides preferred sour. The back of our tongue was sensitive to bitter flavors, and saltiness was sensed everywhere. The sensation of taste was that simple.

If only. We now know that our taste receptors are exquisitely complicated little sensors, and that there are at least five different receptor types scattered all over the mouth, not four. (The fifth receptor is sensitive to the amino acid glutamate, aka umami.) Furthermore, the tongue is only a small part of flavor: As anyone with a stuffy nose knows, the pleasure of food largely depends on its aroma. In fact, neuroscientists estimate that up to 90 percent of what we perceive as taste is actually smell. (…)

Perhaps the most shocking discovery from this new science of taste, however, is that the act of eating is not the only source of gustatory pleasure. Instead, a big chunk part of our sensory delight — the joy that makes us crave particular foods — comes afterwards, when the food is winding its way through the gut.

{ Wired | Continue reading }

food, drinks, restaurants, science | June 30th, 2011 1:19 pm

Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness, the causes of which are not yet well understood. It afflicts about 1% of the population, typically emerging in late adolescence or early adulthood. Neuroimaging and functional testing identify diminished brain volume in key areas and declining cognitive and social functioning at the time that symptoms of the disease emerge. After onset, the symptoms persist, although their intensity fluctuates and some long-term research has identified patients in whom symptoms have dissipated many years after onset. Psychotropic drugs relieve symptoms such as hallucinations and paranoid delusions for some patients, but they have no effect on cognitive or social functioning.

{ Housing and Mental Illness | Harvard University Press | Continue reading }

artwork { Izumi Kato }

health, ideas, neurosciences | June 29th, 2011 4:00 pm

We don’t quite understand small probabilities.

You often see in the papers things saying events we just saw should happen every ten thousand years, hundred thousand years, ten billion years. Some faculty here in this university had an event and said that a 10-sigma event should happen every, I don’t know how many billion years.

So the fundamental problem of small probabilities is that rare events don’t show in samples, because they are rare. So when someone makes a statement that this in the financial markets should happen every ten thousand years, visibly they are not making a statement based on empirical evidence, or computation of the odds, but based on what? On some model, some theory.

So, the lower the probability, the more theory you need to be able to compute it. Typically it’s something called extrapolation, based on regular events and you extend something to what you call the tails. (…)

The smaller the probability, the less you observe it in a sample, therefore your error rate in computing it is going to be very high. Actually, your relative error rate can be infinite, because you’re computing a very, very small probability, so your error rate is monstrous and probably very, very small. (…)

There are two kinds of decisions you make in life, decisions that depend on small probabilities, and decisions that do not depend on small probabilities. For example, if I’m doing an experiment that is true-false, I don’t really care about that pi-lambda effect, in other words, if it’s very false or false, it doesn’t make a difference. (…) But if I’m studying epidemics, then the random variable how many people are affected becomes open-ended with consequences so therefore it depends on fat tails. So I have two kinds of decisions. One simple, true-false, and one more complicated, like the ones we have in economics, financial decision-making, a lot of things, I call them M1, M1+.

{ Nassim Nicholas Taleb/Edge | Continue reading }

economics, ideas, mathematics | June 28th, 2011 1:39 pm

{ A black-headed female Gouldian finch, Erythrura gouldiae, chooses her mate. Having a genetically incompatible mate can increase a female bird’s stress hormone levels which then can affect the sex ratio of her offspring. | Nature | Continue reading }

related { Effects of stress can be inherited, and here’s how }

birds, relationships, science | June 28th, 2011 1:16 pm

Lanchester Theory and the Fate of Armed Revolts

Major revolts have recently erupted in parts of the Middle East with substantial international repercussions. Predicting, coping with and winning those revolts have become a grave problem for many regimes and for world powers. We propose a new model of such revolts that describes their evolution by building on the classic Lanchester theory of combat.

The model accounts for the split in the population between those loyal to the regime and those favoring the rebels. We show that, contrary to classical Lanchesterian insights regarding traditional force-on-force engagements, the outcome of a revolt is independent of the initial force sizes; it only depends on the fraction of the population supporting each side and their combat effectiveness.

{ arXiv | Continue reading | Related: Lanchester’s Theory of Warfare }

photo { Clint Eastwood photographed by Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin }

fights, science | June 28th, 2011 1:14 pm

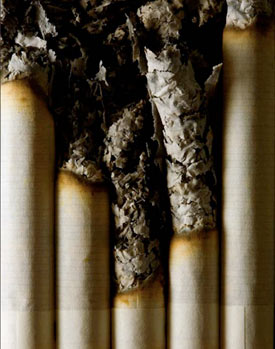

Nicotine is not only very, very addictive, as a central nervous system stimulant it can also affect our motivations and behaviors in a wider sense. One of the behaviors it can modify is appetitive behavior. It’s a well-funded fact that smokers tend to have a lower body-mass than non-smokers, and that smokers who quit have a tendency to gain weight, although until now the neurobiological mechanism for this modulation was unknown.

Recent findings from two different publications reveal parts of this mechanism, but while most reports have pin-pointed the results involving appetite suppression through pro-opiomelanocortin neurons, there is evidence that the complete picture is more complicated than that.

{ Ego Sum Daniel | Continue reading }

photo { Penny Cottee }

science, smoking | June 28th, 2011 1:13 pm

Previous studies have shown that dogs are capable of a remarkable range of human-like behaviours; they have been shown to perform as well or even better than chimpanzees at responding to human body language, verbal commands and attention states.

This has led to debate as to whether dogs are aware of people’s behaviour and can predict how a person will act as a result of it, or whether they are simply responding to the presence or absence of certain stimuli.

Publishing in the journal Learning & Behaviour, Udell and colleagues carried out two experiments to test the ability of pet dogs, rescue shelter dogs and wolves, to successfully beg for food from an attentive individual, versus an inattentive individual. (…)

In the first experiment, two people simultaneously offered food to the subject dog or wolf. One person was always attentive, giving the animal eye contact, while the other was unable to see the animal as they either had a camera or book obscuring their eyes, their back turned or a bucket over their head. (…)

The results showed, for the first time, that wolves as well as domestic dogs tended to beg for food from an attentive individual rather someone who was not paying attention. (…)

“The logical conclusion of the study must be that both genetics and the environment can play a role in the dogs’ behaviour, but the fundamental aspect seems to be genetic with only fine tuning being done by the dogs’ experience in the human environment,” he added.

{ Cosmos | Continue reading }

dogs, science | June 28th, 2011 1:12 pm