[Just keeping alive, M’Coy said] In vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean, there is forty-eight times as much plastic as phytoplankton

quote { via Orion Magazine }

quote { via Orion Magazine }

The Type A and Type B personality theory is a personality type theory that describes a pattern of behaviors that were once considered to be a risk factor for coronary heart disease. Since its inception in the 1950s, the theory has been widely criticized for its scientific shortcomings. It nonetheless persists in the form of pop psychology within the general population.

Type A individuals can be described as impatient, time-conscious, controlling, concerned about their status, highly competitive, ambitious, business-like, aggressive, having difficulty relaxing; and are sometimes disliked by individuals with Type B personalities for the way that they’re always rushing. They are often high-achieving workaholics who multi-task, drive themselves with deadlines, and are unhappy about delays. Because of these characteristics, Type A individuals are often described as “stress junkies.”

Type B individuals, in contrast, are described as patient, relaxed, and easy-going, generally lacking an overriding sense of urgency. Because of these characteristics, Type B individuals are often described by Type A’s as apathetic and disengaged.

There is also a Type AB mixed profile for people who cannot be clearly categorized.

Type A behavior was first described as a potential risk factor in coronary disease in the 1950s by cardiologists Meyer Friedman and R. H. Rosenman. After a nine-year study of healthy men, aged 35–59, Friedman & Rosenman estimated that Type A behavior doubles the risk of coronary heart disease in otherwise healthy individuals. This research had an enormous effect in stimulating the development of the field of health psychology, in which psychologists look at how a person’s mental state affects his or her physical health.

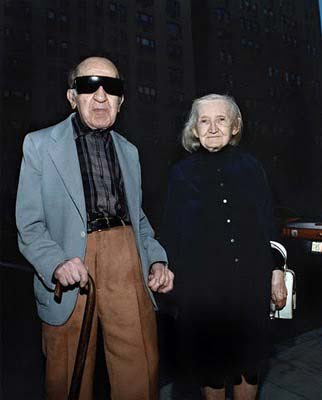

photo { Abbey Drucker }

The advice of etiquette experts on dealing with unwanted invitations, or overly demanding requests for favours, has always been the same: just say no. That may have been a useless mantra in the war on drugs, but in the war on relatives who want to stay for a fortnight, or colleagues trying to get you to do their work, the manners guru Emily Post’s formulation – “I’m afraid that won’t be possible” – remains the gold standard. (…) These are variations on a theme: the best way to say no is to say no. Then shut up. (…)

There are certainly profound issues here, of self-esteem, guilt, et cetera. But it’s also worth considering whether part of the problem doesn’t originate in a simple misunderstanding between two types of people: Askers and Guessers.

This terminology comes from a brilliant web posting by Andrea Donderi. We are raised, the theory runs, in one of two cultures.

In Ask culture, people grow up believing they can ask for anything – a favour, a pay rise– fully realising the answer may be no. In Guess culture, by contrast, you avoid “putting a request into words unless you’re pretty sure the answer will be yes… A key skill is putting out delicate feelers. If you do this with enough subtlety, you won’t have to make the request directly; you’ll get an offer. Even then, the offer may be genuine or pro forma; it takes yet more skill and delicacy to discern whether you should accept.”

Neither’s “wrong”, but when an Asker meets a Guesser, unpleasantness results. An Asker won’t think it’s rude to request two weeks in your spare room, but a Guess culture person will hear it as presumptuous and resent the agony involved in saying no. Your boss, asking for a project to be finished early, may be an overdemanding boor – or just an Asker, who’s assuming you might decline.

If you’re a Guesser, you’ll hear it as an expectation. This is a spectrum, not a dichotomy, and it explains cross-cultural awkwardnesses, too: Brits and Americans get discombobulated doing business in Japan, because it’s a Guess culture, yet experience Russians as rude, because they’re diehard Askers.

{ Thanks Douglas }

In the realm of public policy, we live in an age of numbers. To hold teachers accountable, we examine their students’ test scores. To improve medical care, we quantify the effectiveness of different treatments. There is much to be said for such efforts, which are often backed by cutting-edge reformers. But do wehold an outsize belief in our ability to gauge complex phenomena, measure outcomes and come up with compelling numerical evidence? A well-known quotation usually attributed to Einstein is “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” I’d amend it to a less eloquent, more prosaic statement: Unless we know how things are counted, we don’t know if it’s wise to count on the numbers.

The problem isn’t with statistical tests themselves but with what we do before and after we run them.

{ A Jefferson County teacher picked the wrong example when he used assassinating President Barack Obama as a way to teach angles to his geometry students. Someone alerted authorities and the Corner High School math teacher was questioned by the Secret Service, but was not taken into custody or charged with any crime. | Alabama Live | full story }

Many creatures demonstrate various kinds of collective behavior: birds flock, fish shoal, cattle herd and even humans collaborate from time to time.

Determining the dynamics of this kind of behavior is a hot problem that has lead to a number of fundamental discoveries in recent years. Who would have imagined that bacterial colonies cooperate when they grow, that shoals of fish can make collective decisions and that an insect swarm can act seemingly as one? And yet the mathematics that describe these systems demonstrate how easily this kind of behavior can emerge.

Today, the mathematics of animal synchrony takes a cloven-footed step forward with the unveiling of a model that describes the collective behavior of cows.

Cows are well know for their collective behavior: they tend to either all lie down or all stand up for example. Jie Sun at Clarkson University in New York state and colleagues say that this behavior can be modelled by thinking of cows as simple oscillators: they either stand or lie and do this in cycles. These oscillators are also coupled: one form of coupling may be that a cow is more likely to lie down if those around it are lying down and vice versa.

The result is a mathematical model in which the collective behavior of cows can be studied in abstract.

As Mr. Tahiri spoke, an Afghan soldier appeared carrying a large red trash bag. It was, he said, filled with human brains. “What do you want me to do with this,” he asked. “Do you want me to bury it, or do you want to take it?”

What does it mean to be white?

A controversial new book, The History of White People, claims that Barack Obama is, to all intents and purposes, white. Not because he had a white mother but because of his educational background, his income, his power, his status. The book’s author, the eminent black American historian Nell Irvin Painter, has written a fascinating, sprawling history of the concept of race, looking specifically at the idea of a white race and at why and how whites have dominated other, darker-skinned races throughout recent centuries. The conclusion of Painter’s book – which has taken more than a decade to research and write – is explosive. Race, she argues, is a fluid social construct, entirely unsupported by scientific fact. Like beauty, it is merely skin-deep.

{ Mark Rothko, No.14, 1960 | Unrelated: A way of reconstructing randomly scattered images allows pictures to be transmitted through opaque objects. | How to take photographs through opaque objects | full story }

Despite their time in therapy, men still don’t have a clue about what their wives and therapists want from them. (…) Most of my male clients feel that their previous therapy experience was about forcing them to fit a template of what the Therapy World believes love and relationships should look like. While the therapeutic language of “intimacy” is supposedly gender-neutral, most men see it as reflecting values and ideals that appeal disproportionately to women. (…)

The reason men can talk about feelings and relationship patterns in consultation rooms, but are unlikely to keep doing it at home is simple: emotional talk tends to produce more physiological arousal in men—they experience it more stressfully. Unlike women, they don’t get the oxytocin reward that makes them feel calm, secure, and confident when talking about emotions and the complexities of relationships; testosterone, which men produce more of during stress, seems to reduce the effect of oxytocin, while estrogen enhances it. It takes more work with less reward for men to shift into and maintain the active-listening and self-revealing emotional talk they learn in therapy, so they’re unlikely to do it on a routine basis. (…)

Men have to feel compelling reasons to change and, most important, to incorporate new behavior into their daily routine. I believe that the primary motivation keeping men invested in loving relationships is different from what keeps women invested, that it has a strong biological underpinning present in all social animals, and that it’s been culturally reinforced throughout the development of the human species.

The glue that keeps men (and males in social animal groups) bonded is the instinct to protect. If you listen long enough to men talking about what it means to love, you’ll notice that loving is inextricably linked, for many men, to some form of protection. If men can’t feel successful at protecting, they can’t fully love.

The main role of males in social groups throughout the animal world is to protect the group from outside threats. For the most part, males participate in packs and herds only if the group has predators or strong competition for food. Herds and packs without predators or competitors, like elephants and hippos, are matriarchal, with males either absent or playing peripheral or merely sperm-donor roles.

Male physiology is well-evolved for group protection, with greater muscle mass, more efficient blood flow to the muscles and organs, bigger fangs and claws, quicker reflexes, longer strides, more electrical activity in the central nervous system (to stimulate organs and muscle groups), and a thicker amygdala—the organ that activates the flight or fight response. That’s right, the first emergency response in male social animals is flight, with the option to fight coming into play only when flight isn’t possible. The principal protective role of males in social groups is to lead the pack to safety. (…)

As historian Stephanie Coontz puts it, previous generations widely assumed that men and women had different natures and couldn’t truly understand each other. The idea of intergender emotional talk independent of the need to protect didn’t emerge until the dissolution of the extended family, which began in the middle of the 20th century. Previous to that, the nuclear family—an intimate couple and children living as an isolated unit—was a rarity. Other family members were in the same house, next door, or across the street. Women got their emotional validation from other women, although they certainly wanted admiration from their men and vice versa. Today, research shows that the healthiest, happiest women have a strong network of girlfriends. In earlier times, men tended to associate mostly with other men—a cultural construct that’s still prevalent in many parts of the world, frequently reinforced by religious beliefs. (…)

Couples typically find it particularly interesting that males remain connected to social animal groups by proximity to the females, even though they don’t interact much, while the females enhance group cohesion by frequently interacting with one another. If the couple has had a boy and girl toddler, they can see this difference in social orientation for themselves early on. Assuming that the children are both securely attached, the boy will tend to play in proximity to the caregiver, always checking to see that he or she is there, but seeking far fewer direct interactions—talking, asking questions, making eye contact, touching, hugging—than the girl. As long as he knows his caregiver is present, his primary interaction is with the environment.

Similarly, a man can feel close to his wife if he’s in one room—on the computer, in front of the TV, or going about his routine—and she’s in another. He’ll likely protest, sulk, or sink into loneliness if she goes out, which she may well do since he isn’t talking to her anyway. To her, and to uninformed therapists, it seems that he wants her home so he can ignore her. But he isn’t ignoring her; her presence gives stability to his routine.

This little example of why proximity to his wife is crucial to him works wonders in opening a man’s eyes to that fact that his wife gives meaning and purpose to his life. In fact, we tend to think about meaning or purpose only when we’re losing it, which is why men tend to fall in love with their wives as they’re walking out the door, with their bags packed. Evidence for the drastic loss of meaning and purpose that men suffer when they lose their wives is seen in the effects of divorce and widowerhood on men: poorer job performance, impaired problem-solving, lowered creativity, high distractibility, “heavy foot” on the gas while driving, anxiety, worry, depression, resentment, anger, aggression, alcoholism, poor nutrition, isolation, shortened lifespan, and suicide. The divorced or widowed man isn’t merely lonely—he’s alone with the crushing shame of his failure to protect his family.

I’m able to use education about the effects of divorce on men clinically, because most guys know someone at work who’s lost his family and become a shadow of his former self. As a quick way of accessing men’s fundamental sense of the meaning and purpose of their lives, I ask each man to write down what he thinks is the most important thing about him as a person. “How do you want those you love to remember you,” I ask. “Near the end of your life, what will you most regret not doing enough of?”

Because meaning and purpose are elusive psychological concepts—a way of describing why we do something rather than what we do—men will rarely hit the mark at first. They say they want to be remembered as a “good provider,” “hard worker,” “loyal man,” choosing mostly protective terms. I then ask them to imagine that they have grown children and how they’d most like their children to feel about them when they’re gone. “Dad was a good provider, hard worker, loyal, etc. I’m not sure he cared about us, but he was a good provider, worked, and was loyal” or “Dad was human; he made mistakes. But I always knew that he cared about us and wanted what was best for us.” On a deep level, all the men I’ve worked with have wanted to be remembered with some version of the second statement—as both protective and compassionate. Helping men learn to express care and compassion directly to the people they love is the key to bridging the divide between their protective instinct and their reluctance to show their emotions. (…)A major challenge to lasting change in marriage lies in the fact that couples’ day-to-day interactions operate largely on automatic pilot. Emotional response is triggered predominantly by unconscious cues, such as body language, tone of voice, and level of mental distractedness. Negativity in any of these inadvertently sets off the automatic defense system that’s developed between the parties. Once triggered, the unaware couple can easily spiral into dysfunctional patterns of relating. They tend to get lost in the details of whatever they’re blaming on each other, with no realization of what’s actually happened to them—namely, an inadvertent triggering of the automatic defense system. (…)

Rather than forcing themselves to act like the same instruments playing the same notes in a duet, couples who begin to interact in this way become like two different instruments playing different notes to create something together that neither can do individually—relational harmony.

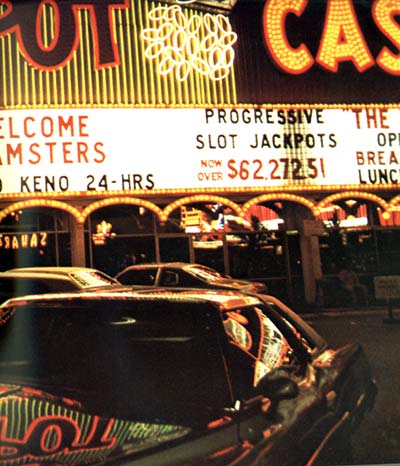

Why are gamblers such a difficult subject for academic study?

“We have both spent over 10 years playing in and researching this area, and we can offer some explanations on why it is so hard to gather reliable and valid data,” wrote psychologists Mark Griffiths, of Nottingham Trent University, and Jonathan Parke, of Salford University explained, in a monograph called Slot Machine Gamblers – Why Are They So Hard to Study?

Here are three from their long list.

First, gamblers become engrossed in gambling. “We have observed that many gamblers will often miss meals and even utilise devices (such as catheters) so that they do not have to take toilet breaks. Given these observations, there is sometimes little chance that we as researchers can persuade them to participate in research studies.”

Second, gamblers like their privacy. They “may be dishonest about the extent of their gambling activities to researchers as well as to those close to them.” (…)

Third, gamblers sometimes notice when a person is spying on them. “The most important aspect of non-participant observation research while monitoring fruit-machine players is the art of being inconspicuous. If the researcher fails to blend in, then slot-machine gamblers soon realise they are being watched and are therefore highly likely to change their behaviour.”

Psychopathy is a personality disorder manifested in people who use a mixture of charm, manipulation, intimidation, and occasionally violence to control others, in order to satisfy their own selfish needs. Although the concept of psychopathy has been known for centuries, the FBI leads the world in the research effort to develop a series of assessment tools, to evaluate the personality traits and behaviors attributable to psychopaths.

Interpersonal traits include glibness, superficial charm, a grandiose sense of self-worth, pathological lying, and the manipulation of others. The affective traits include a lack of remorse and/or guilt, shallow affect, a lack of empathy, and failure to accept responsibility. The lifestyle behaviors include stimulation-seeking behavior, impulsivity, irresponsibility, parasitic orientation, and a lack of realistic life goals.

Research has demonstrated that in those criminals who are psychopathic, scores vary, ranging from a high degree of psychopathy to some measure of psychopathy. However, not all violent offenders are psychopaths and not all psychopaths are violent offenders. If violent offenders are psychopathic, they are able to assault, rape, and murder without concern for legal, moral, or social consequences. This allows them to do what they want, whenever they want. Ironically, these same traits exist in men and women who are drawn to high-profile and powerful positions in society including political officeholders.

The relationship between psychopathy and serial killers is particularly interesting. All psychopaths do not become serial murderers. Rather, serial murderers may possess some or many of the traits consistent with psychopathy. Psychopaths who commit serial murder do not value human life and are extremely callous in their interactions with their victims. This is particularly evident in sexually motivated serial killers who repeatedly target, stalk, assault, and kill without a sense of remorse. However, psychopathy alone does not explain the motivations of a serial killer.

What doesn’t go unnoticed is the fact that some of the character traits exhibited by serial killers or criminals may be observed in many within the political arena. While not exhibiting physical violence, many political leaders display varying degrees of anger, feigned outrage and other behaviors. They also lack what most consider a “shame” mechanism. Quite simply, most serial killers and many professional politicians must mimic what they believe, are appropriate responses to situations they face such as sadness, empathy, sympathy, and other human responses to outside stimuli.

Gaze direction affects judgements of facial attractiveness

Much is known about the attractiveness of physical attributes, such as symmetry and averageness. Here we examine the effect of a social cue, eye-gaze direction, on facial attractiveness. Given that direct gaze signals social engagement, we predicted that faces showing direct gaze would be preferred to faces showing averted gaze.

Thirty-two males completed two tasks designed to assess preferences for female faces displaying a neutral expression. Participants were more likely to select the face with direct gaze, when choosing the more attractive face from direct- and averted-gaze versions of the same face.

This direct-gaze preference was stronger for high-attractive than low-attractive face sets, but was present for both. Attractiveness ratings were also higher for faces with direct than averted gaze. Interestingly, stimulus inversion weakened the preference for inverted faces, which suggests the preference does not simply reflect a bilateral symmetry bias.

{ Visual Cognition/InformaWorld }

Gaze bias: Selective encoding and liking effects

People look longer at things that they choose than things they do not choose. How much of this tendency—the gaze bias effect—is due to a liking effect compared to the information encoding aspect of the decision-making process? (…)

Colour content (whether a photograph was colour or black-and-white), not decision type, influenced the gaze bias effect in the older/newer decisions because colour is a relevant feature for such decisions. These interactions appear early in the eye movement record, indicating that gaze bias is influenced during information encoding.

photo { Morad Bouchakour }

Competitors playing a match against Bobby Fischer, perhaps the greatest chess player of all time, often came down with a mysterious affliction known as “Fischer-fear.” Even fellow grandmasters were vulnerable to the effect, which could manifest itself as flu-like symptoms, migraines and spiking blood pressure. As Boris Spassky, Mr. Fischer’s greatest rival, once said: “When you play Bobby, it is not a question of whether you win or lose. It is a question of whether you survive.”

Recent research on what is known as the superstar effect demonstrates that such mental collapses aren’t limited to chess. While challenging competitions are supposed to bring out our best, these studies demonstrate that when people are forced to compete against a peer who seems far superior, they often don’t rise to the challenge. Instead, they give up. (…)

Because his competitors expect him to win, they end up losing; success becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. (…)

In the early 1960s, the psychologist Sam Glucksberg demonstrated that the same effect could also inhibit creativity. He gave subjects a standard test of creativity known as the Duncker candle problem. The “high drive” group was told that the person solving the task in the shortest amount of time would receive $20. The “low drive” group, in contrast, was reassured that their speed didn’t matter. Here’s where the results get weird: The subjects with an incentive to think quickly took, on average, more than three minutes longer to find the answer. Experiments like this have led Ms. Beilock to conclude that people should be skeptical of evaluations based on a single high-stakes performance.

The cure for procrastination? Forgive yourself!

There are so many things you’d rather be doing than what you ought to be doing and what happens is that you delay doing what you ought. All the evidence shows that this procrastination is bad for you, for your productivity, your school grades, for your health. But still we keep putting things off. Until. Tomorrow. Now Michael Wohl and colleagues have proposed a rather surprising cure - self-forgiveness. That’s right, forgive yourself for you have procrastinated, move on, get over it and you’ll be more likely to get going without delay next time around.

photo { Alison Brady }

Empathy is a complicated emotion, even for mice. On seeing another in pain, a mouse will act as if it itself is also hurting—but only if it knows the first mouse. Monkeys, too, will feel bad for another monkey, but only if they’re on friendly terms. People also feel less empathy for those they dislike. But our species adds another layer of complication: We empathize more with people who are “like us” than with “them.” This study, published this month, suggests that this Us-Them divide is more general—that the brain responds differently to any action performed by “one of us,” not just to signs of trouble.

The study is part of a boom in research around the idea that people literally share feelings, at the physiological level: When I see you in pain, for example, neurons fire in my brain just as they would if I myself were in pain. It’s an intriguing notion, not least because it offers a way to integrate aspects of human behavior that are usually looked at separately. Empathy is a social fact, arising out of people’s relationships to each other; and it’s a psychological experience for each of us; and it’s a physiological phenomena in each empathizer’s body. A model that connects those different levels would offer a more complete explanation. It would also, of course, offer ways to corroborate theories: It’s great to be able to ask people if they feel empathy, but it’s even better if you can measure it as well.

When we’re creative, we feel we are living more fully than during the rest of life. The excitement of the artist at the easel or the scientist in the lab comes close to the ideal fulfillment we all hope to get from life, and so rarely do. Perhaps only sex, sports, music, and religious ecstasy—even when these experiences remain fleeting and leave no trace—provide a profound sense of being part of an entity greater than ourselves. But creativity also leaves an outcome that adds to the richness and complexity of the future.

I have devoted 30 years of research to how creative people live and work, to make more understandable the mysterious process by which they come up with new ideas and new things. Creative individuals are remarkable for their ability to adapt to almost any situation and to make do with whatever is at hand to reach their goals. If I had to express in one word what makes their personalities different from others, it’s complexity. They show tendencies of thought and action that in most people are segregated. They contain contradictory extremes; instead of being an “individual,” each of them is a “multitude.”

Here are the 10 antithetical traits often present in creative people that are integrated with each other in a dialectical tension.

illustration { saimanchow }

A new scheme for making quantum money could lead to cash that cannot be counterfeited. But it may also lead to a new breed of quantum crime.

In the last couple of years, a number of quantum dignitaries have become interested in the (relatively) ancient problem of quantum money.

The challenge is to create a quantum state that can work as a form of money. Just like ordinary cash, quantum cash would be exchanged in lieu of goods. It would be sent and received over the internet without the need to involve third party parties such as banks and credit card companies. That would make transactions anonymous and difficult to trace, unlike today’s online transactions which always leave an electronic paper trail. That’s one big advantage over today’s money.

Another is that quantum states cannot be copied so quantum cash cannot be forged.

But quantum cash must have another property: anybody needs to be able to check that the money is authentic. That turns out to be hard because measurements on quantum states tend to destroy them. It’s like testing classical bills by seeing whether they burn.

Happier people tend to think about themselves with higher level of abstraction than less happy people, even after controlling for the overall valence and internality of their construals. … People randomly assigned to think about themselves in abstract rather than concrete terms reported greater pre- to post-manipulation increases in reports of life satisfaction.

{ via Overcoming Bias | Continue reading | Fortune favors the bold | Wikipedia }