Now you steppin wit a G, from Los Angeles, where the helicopters got cameras

The third (and last) time I went to New Orleans was in September of 1978. I was living in Marin County, and I took the red-eye out of San Francisco, flying on a first-class ticket paid for by Universal Pictures, the studio that was financing the movie I was contracted to write. The story was to be loosely based on an article written by Hunter Thompson that had been recently published in Rolling Stone magazine. Titled “The Banshee Screams for Buffalo Meat,” the 30,000-word piece detailed many of the (supposedly) true-life adventures Hunter had experienced with Oscar Zeta Acosta, the radical Chicano lawyer who he’d earlier canonized in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

Hunter and I were in New Orleans to attend the hugely anticipated rematch between Muhammad Ali and Leon Spinks, the former Olympic champion who, after only seven fights, had defeated Ali in February. The plan was to meet up at the Fairmont, a once-elegant hotel that was located in the center of the business district and within walking distance of the historic French Quarter. Although Hunter was not in his room when I arrived, he’d instructed the hotel management to watch for me and make sure I was treated with great respect.

“I was told by Mister Thompson to mark you down as a VIP, that you were on a mission of considerable importance,” said Inga, the head of guest services, as we rode the elevator up to my floor. “Since he was dressed quite eccentrically, in shorts and a Hawaiian shirt, I assumed he was pulling my leg. The bellman who fetched his bags said he was a famous writer. Are you a writer also?” I told her I wrote movies. “Are you famous?”

“No.”

“Do you have any cocaine?”

I stared at her. Her smile was odd, both reassuring and intensely hopeful. In the cartoon balloon I saw over her head were the words: I’m yours if you do. “Yes, I do.”

“That is good.”

Inga called the hotel manager from my room and told him, in a voice edged with professional disappointment, that she was leaving early because of a “personal matter.” After she hung up, she dialed room service and handed me the phone. She directed me to order two dozen oysters, a fifth of tequila, and two Caesar salads. Then, with a total absence of modesty, she quickly stripped off her clothes, walked into the bathroom, and a moment later I heard the water running in the shower.

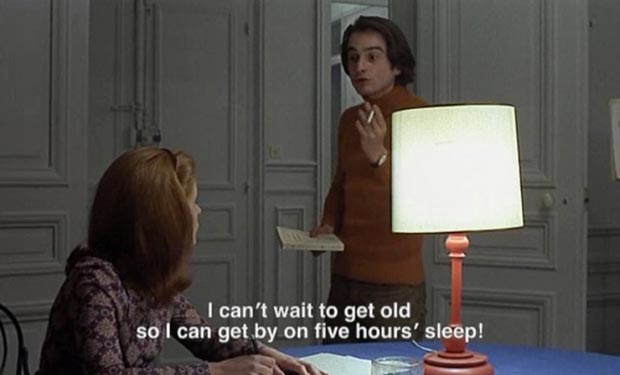

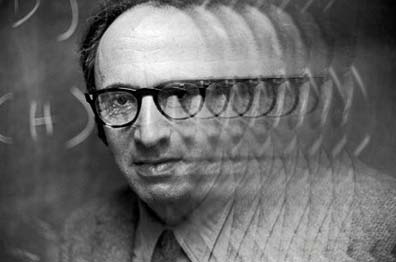

photo { Richard Kern | More: Shot by Kern | videos }