flashback

Cannibalism is part of the great cultural legacies of our species. In times past, for instance, we would eat our honoured dead to gain their wisdom.

In medieval times, it was believed that memories were stored in the cerebrospinal fluid. Sadly, it seems that memory cannot be transferred biochemically. (…)

In the Polynesian islands, human meat has always been known as “long pig,” because people taste like pork.

{ Warren Ellis/Wired | Continue reading }

flashback, food, drinks, restaurants, weirdos | December 17th, 2010 4:56 pm

flashback, health, mozart, music | December 14th, 2010 6:02 pm

It is not surprising that theologians and artists clashed over the Last Supper. Common meals were the center of social life in Renaissance Europe, everywhere from ascetic, remote monasteries to bankers’ and cardinals’ lush gardens in the middle of Trastevere. And they were always a battleground of opposing ideals of austerity and consumption. (…)

But what should a Last Supper look like? What did Christ and the Apostles eat? And how much? When Jesus distributed pieces of bread, was it leavened or unleavened? What other foodstuffs had been on the table? Did the followers of Jesus eat lamb, as Jews normally did at Passover? Over the centuries—as an article in the International Journal of Obesity recently showed—artists made many different choices. Sometimes they put lamb on the table. But they also served fish, beef, and even pork in portions that grew over the centuries.

{ Cabinet | Continue reading }

painting { Dirck van Baburen, Roman Charity, Cimon and Peres, ca. 1623 }

art, flashback, food, drinks, restaurants | December 13th, 2010 8:20 pm

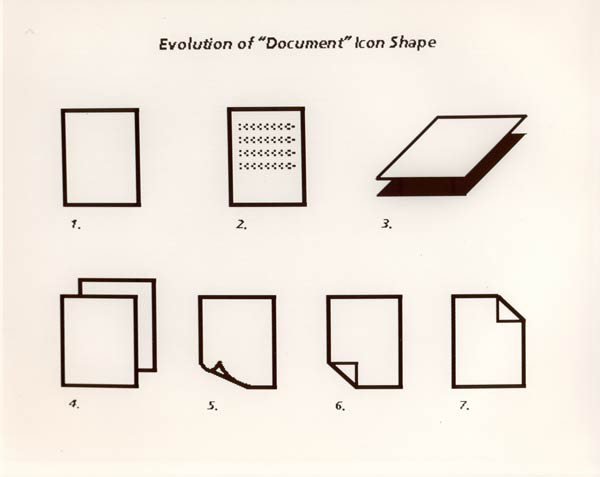

flashback, technology, visual design | December 13th, 2010 7:40 pm

William James Sidis (1898-19444) showed astonishing intellectual qualities from an exceptionally early age. By the age of one he had learned to spell in English. He taught himself to type in French and German at four and by the age of six had added Russian, Hebrew, Turkish and Armenian to his repertoire. At five he devised a system which could enable him to name the day of the week on which any date in history fell. Hot-housed by his pushy father, Sidis entered Harvard at eleven, and was soon lecturing on 4 dimensional bodies to the University’s Maths Society.

At twelve he suffered his first nervous breakdown, but recovered at his father’s sanatorium, and after returning to Harvard, graduated with first class honours in 1914, aged just sixteen. Law School followed and by the age of twenty Sidis had become a professor of maths at Texas Rice Institute. (…)

Sidis was just 27 when he predicted the existence of what we now know as ‘black holes.’

{ Bookride | Continue reading }

In his adult years, it was estimated that he could speak more than forty languages, and learn a new language in a day. (…)

Sidis created a constructed language called Vendergood in his second book, entitled Book of Vendergood, which he wrote at the age of eight. The language was mostly based on Latin and Greek, but also drew on German and French and other Romance languages. (…)

Sidis was also a “peridromophile,” a term he coined for people fascinated with transportation research and streetcar systems.

{ Wikipedia }

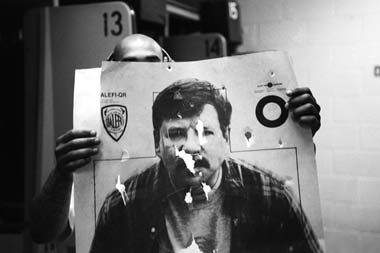

photo { Aaron Feaver }

experience, flashback | December 13th, 2010 7:10 pm

Pont St. Esprit is a small town in southern France. In 1951 it became famous as the site of one of the most mysterious medical outbreaks of modern times.

As Dr’s Gabbai, Lisbonne and Pourquier wrote to the British Medical Journal, 15 days after the “incident”:

The first symptoms appeared after a latent period of 6 to 48 hours. In this first phase, the symptoms were generalized, and consisted in a depressive state with anguish and slight agitation.

After some hours the symptoms became more clearly defined, and most of the patients presented with digestive disturbances… Disturbances of the autonomic nervous system accompanied the digestive disorders-gusts of warmth, followed by the impression of “cold waves”, with intense sweating crises. We also noted frequent excessive salivation.

The patients were pale and often showed a regular bradycardia (40 to 50 beats a minute), with weakness of the pulse. The heart sounds were rather muffled; the extremities were cold… Thereafter a constant symptom appeared - insomnia lasting several days… A state of giddiness persisted, accompanied by abundant sweating and a disagreeable odour. The special odour struck the patient and his attendants.

In total, about 150 people suffered some symptoms. About 25 severe cases developed the “delirium”. 4 people died “in muscular spasm and in a state of cardiovascular collapse”; three of these were old and in poor health, but one was a healthy 25-year-old man.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

flashback, health, mystery and paranormal | November 29th, 2010 4:00 pm

The documents of Mozart’s life — letters, memoirs of friends, portraits, bureaucratic files — have long been scrutinized at a microscopic level. So when his name was discovered two decades ago in a Viennese archive from 1791, it caused a stir.

The archive showed that an aristocratic friend and fellow Freemason, Prince Karl Lichnowsky, had sued Mozart over a debt and won a judgment of 1,435 florins and 32 kreutzer in Austrian currency of the time (nearly twice Mozart’s yearly income) weeks before the composer died.

The entry was a mystery. No other information about the judgment has come to light, although scholars have generally assumed that it concerned a loan connected with a trip the two men made to Berlin.

Now a Mozart scholar, Peter Hoyt, has come up with a theory about the details: that the judgment stemmed from a loan of 1,000 thalers in Prussian currency made on May 2, 1789, the day the prince and his coach departed Berlin without Mozart, leaving him in need of money for his own transportation.

If true, the conclusion could add depth and texture to our understanding of Mozart’s anxieties over financial problems at the end of his life and of his reception during one of his last journeys.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

economics, flashback, mozart | November 29th, 2010 4:00 pm

Imagine American history without organized crime. (…)

In Chicago and New York, Italian and Jewish gangsters operated many of the most important early jazz clubs. Al Capone, who controlled several of the clubs in Chicago that introduced jazz to mainstream audiences, was an aficionado of the music and was the first to pay performers a better than subsistence wage. (…) According to the scholar Jerome Charyn, “There would have been no ‘Jazz Age,’ and very little jazz, without the white gangsters who took black and white jazz musicians under their wing.” (…)

Though famous for their ultra-masculinity, gangsters were nonetheless instrumental in fostering and protecting the gay subculture during the hostile years of World War II and the 1950s. Vito Genovese and Carlo Gambino, leaders of the largest and most powerful crime families in New York, began investing in gay bars in the early 1930s.

By the 1950s, most of the gay bars in New York were owned by the mob. Because of the mafia’s connections with the police department and willingness to bribe officers, patrons of mob-owned bars were often protected from the police raids that dominated gay life in the 1950s.

{ Thaddeus Russell | Continue reading }

economics, flashback | November 26th, 2010 4:36 pm

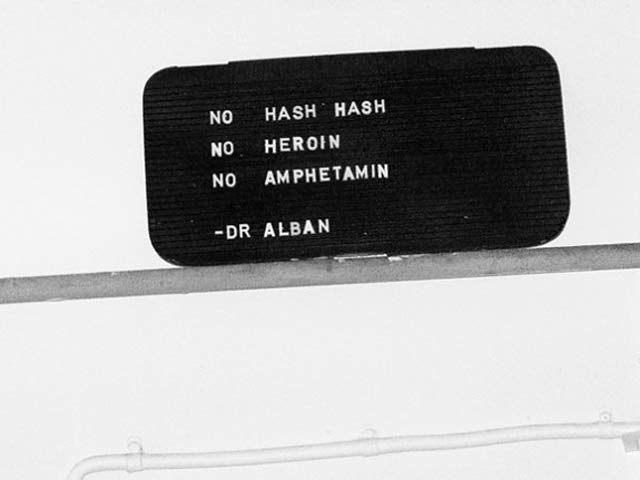

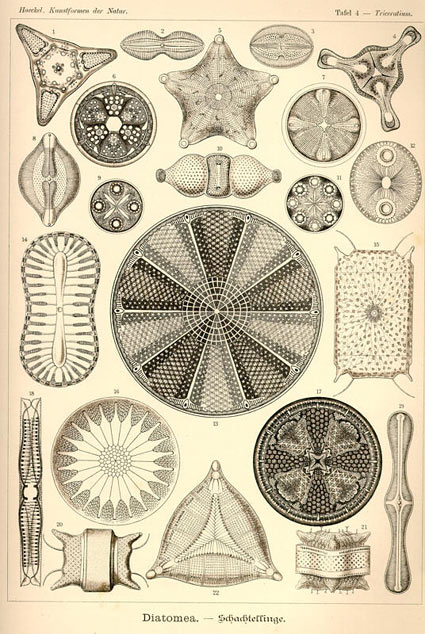

{ Ernst Haeckel, Kunstformen der Natur, 1899-1904 | Ernst Haeckel (1834 – 1919) was an eminent German biologist, naturalist, philosopher, physician, professor and artist who discovered, described and named thousands of new species, mapped a genealogical tree relating all life forms, and coined many terms in biology, including ecology. | Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Linguistics, flashback, science, visual design | November 26th, 2010 4:20 pm

New York City in the 1920s and ’30s was a hotbed of criminal activity. Prohibition laws banning the production, sale and distribution of alcohol had been introduced, but instead of reducing crime, they had the opposite effect. Gangsters organized themselves and seized control of the alcohol distribution racket, smuggling first cheap rum from the Caribbean, then French champagne and English gin, into the country. Speakeasies sprang up in every neighbourhood, and numbered more than 100,000 by 1925. When prohibition was abolished in 1933, the gangsters took to other activities, such as drug distribution, and crime rates continued to increase.

At the forefront of the city’s efforts to keep crime under control was a man named Carleton Simon. Simon trained as a psychiatrist, but his reach extended far beyond the therapist’s couch. He became a ‘drug czar’ six decades before the term was first used, spearheading New York’s war against drug sellers and addicts. He was a socialite and a celebrity, who made a minor contribution to early forensic science by devising new methods to identify criminals. He also tried to apply his knowledge to gain insights into the workings of the criminal brain, becoming, effectively, the first neurocriminologist.

Simon was born in New York City on February 28th, 1871, and studied in Vienna and Paris, graduating with an M.D. in 1890. Afterwards, he conducted sleep research. (…) Eventually, Simon became interested in criminology and psychopathology, and by the turn of the century had abandoned his psychiatric research to focus on these disciplines. (…)

Towards the end of the 1930s crime was estimated to cost the U.S. approximately $15 billion annually. Knowledge of brain function and dysfunction was very rudimentary by today’s standards, and criminals and psychopaths were often lobotomized or subjected to electroconvulsive therapy in order to keep them under control. Another treatment available was insulin shock therapy, which had been introduced by Manfred Sakel in 1933, and involved giving patients large repeated doses of the hormone to induce coma. It was around this time that Simon proposed a new theory, which he believed would help science to understand and control the criminal mind.

The theory drew on the concept of cerebral dominance, which had emerged some 70 years earlier, largely from Paul Broca’s investigations of stroke patients. (…) According to Simon’s theory, criminality occurs as a result of a shift in cerebral dominance, whereby the normally submissive right hemisphere gains mastery of the brain, leading to irrational behaviour.

{ Neurophilosophy | Continue reading }

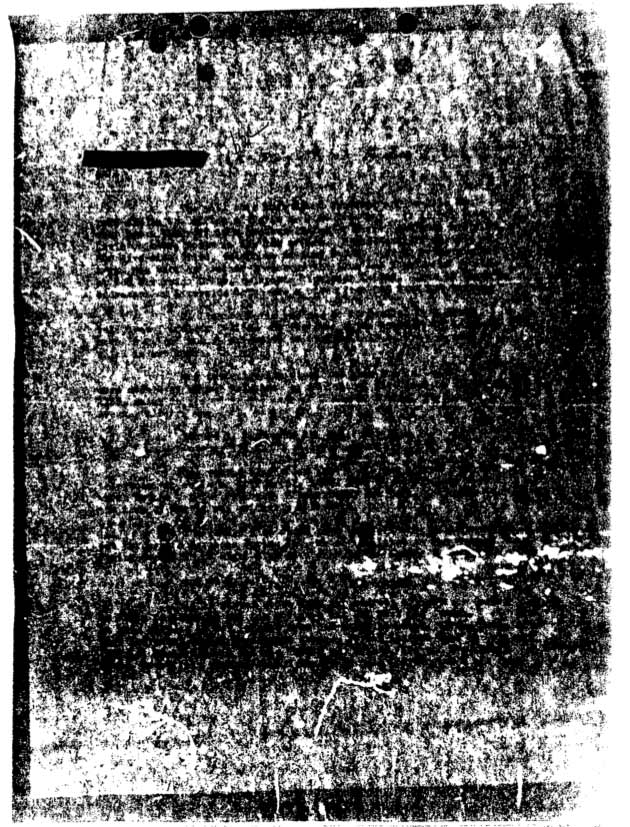

photo { Alessandro Zuek Simonetti }

flashback, neurosciences, new york, science | November 24th, 2010 4:10 pm

I use a method called “Dutching” (named for 1930s New York gangster, “Dutch” Schultz, whose accountant came up with it). With Dutched bets, you make two or more bets on the same race with more money on more favored horses and less money on longer odds horses such that your profit is the same, no matter which horse wins. (…)

I haven’t bet with this strategy yet, but I have found from playing with the data that very often there are opportunities…

{ David Icke’s Official Forums | Wikipedia }

Arthur Flegenheimer, alias Dutch Shultz, was a fugitive from justice. He was wanted in 1934 for Income Tax Evasion. On October 23, 1935, Shultz and three associates were shot by rival gangsters in a Newark, New Jersey restaurant. Shultz’s death started rival gang wars among the hoodlum and underworld gangs.

{ FBI.gov | Continue reading | Read more: By the mid-1920s, Schultz realized that bootlegging was the way to make serious money. }

Linguistics, flashback, horse, law | November 22nd, 2010 8:06 pm

A German researcher has studied medieval criminal law and found that our image of the sadistic treatment of criminals in the Dark Ages is only partly true. Torture and gruesome executions were designed in part to ensure the salvation of the convicted person’s soul. (…)

New access to existing sources, such as law books and pamphlets, has enabled Schild to soften the prevailing view of the past. Many descriptions from centuries past were “distorted and exaggerated to make the past seem particularly dark and the present more radiant,” says Schild.

The Renaissance poet Petrarch, for example, carried this sort of fiction to extremes. He dreamed up the “brazen bull,” a hollow object made of metal that was placed over a fire while the condemned criminals inside were cooked alive. But the executioners of the Middle Ages were not driven by such sadistic impulses.

{ Der Spiegel | Continue reading }

photo { Jocelyn Lee }

flashback, horror | November 16th, 2010 6:40 pm

The famous lifelike poses of many victims at Pompeii—seated with face in hands, crawling, kneeling on a mother’s lap—are helping to lead scientists toward a new interpretation of how these ancient Romans died in the A.D. 79 eruptions of Italy’s Mount Vesuvius.

Until now it’s been widely assumed that most of the victims were asphyxiated by volcanic ash and gas. But a recent study says most died instantly of extreme heat, with many casualties shocked into a sort of instant rigor mortis.

{ National Geographics | Continue reading }

flashback, science | November 15th, 2010 7:00 pm

Francis Wolle, active in the early 1850s, is considered the first inventor of the modern paper bag. Based in Pennsylvania, he cofounded the Union Paper Bag Machine Company in 1869, as well as becoming ordained as a deacon and following passions in entomology and botany. Union was supported financially by wealthy manufacturers, who thereby secured rights to patents secured by the company and divvied up the country into market segments to avoid direct competition. One of these characters was industrialist George West of Saratoga County, New York, also known as the “Paper Bag King.” (…)

The speed and scale of paper-bag production facilitated by Stilwell’s design was revolutionary for the industry. In The Growth of a Century (1894), for example, John A. Haddock describes the Paper Mill and Bag Factory of the Taggart Brothers’ Company in Watertown, NY: “In the bag-manufacturing room they have one machine that makes a bag with satchel-bottom, direct from the roll, at the rate of 3,600 finished bags per hour, completing with ease 25,000 fifty-pound flour sacks in ten hours.

{ MoMA | Continue reading }

photo { Beni Bischof }

economics, flashback | November 14th, 2010 8:06 pm

flashback, music, video | November 14th, 2010 7:40 pm

Sweating sickness, also known as the “English sweate” (Latin: sudor anglicus), was a mysterious and highly virulent disease that struck England, and later continental Europe, in a series of epidemics beginning in 1485. The last outbreak occurred in 1551, after which the disease apparently vanished. The onset of symptoms was dramatic and sudden, with death often occurring within hours. Its cause remains unknown. One suspect is a hantavirus. (…)

The symptoms and signs as described by Caius and others were as follows: The disease began very suddenly with a sense of apprehension, followed by cold shivers (sometimes very violent), giddiness, headache and severe pains in the neck, shoulders and limbs, with great exhaustion. After the cold stage, which might last from half an hour to three hours, the hot and sweating stage followed. The characteristic sweat broke out suddenly without any obvious cause. Accompanying the sweat, or after that was poured out, was a sense of heat, headache, delirium, rapid pulse, and intense thirst. Palpitation and pain in the heart were frequent symptoms. No skin eruptions were noted by observers including Caius. In the final stages, there was either general exhaustion and collapse, or an irresistible urge to sleep, which Caius thought to be fatal if the patient was permitted to give way to it. One attack did not offer immunity, and some people suffered several bouts before succumbing.

The malady was never seen again in England after 1578 although a similar illness, known as the Picardy sweat, occurred in France between 1718 and 1861, but was less likely to be fatal and was accompanied by a rash, which was not a feature of the earlier outbreaks.

The cause is the most mysterious aspect of the disease. Commentators then and now put much blame on the general dirt and sewage of the time, which may have harboured the source of infection. (…)

Relapsing fever has been proposed as a possible cause. This disease, which is spread by ticks and lice, occurs most often during the summer months, as did the original sweating sickness. However, relapsing fever is marked by a prominent black scab at the site of the tick bite and a subsequent skin rash, whereas contemporaries did not note these relatively obvious signs, so the identification is far from certain.

Chronic fatigue syndrome has been suggested by Chaudhuria and Behan based on a 1934 article of epidemic myalgia outbreaks that share clinical similarities with Bornholm disease.

More recently, a hantavirus has been proposed and appears to be an interesting candidate for consideration in the etiology of this illness.[4] However, certain clinical features of hantavirus outbreaks do not seem to match the progression of the sweating sickness; specifically, while hantavirus has only rarely been observed to be transmitted from one human to another, this is believed to be a significant mode of transmission of the sweating sickness.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

photo { Helen Korpak }

flashback, health, mystery and paranormal | November 10th, 2010 5:20 pm

flashback, new york, transportation | November 9th, 2010 5:00 pm

At the forefront of early psychedelic research was a British psychiatrist by the name of Humphry Osmond (1917-2004). In 1951, Osmond moved to Canada to take the position of deputy director of psychiatry at the Weyburn Mental Hospital and, with funding from the government and the Rockefeller Foundation, established a biochemistry research program. The following year, he met another psychiatrist by the name of Abram Hoffer. (…)

The pair hit upon the idea of using LSD to treat alcoholism in 1953, at a conference in Ottawa. (…)

By 1960, they had treated some 2,000 alcoholic patients with LSD, and claimed that their results were very similar to those obtained in the first experiment. Their treatment was endorsed by Bill W., a co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous who was given several sessions of LSD therapy himself, and Jace Colder, director of Saskatchewan’s Bureau on Alcoholism, who believed it to be the best treatment available for alcoholics.

Osmond also “turned on” Aldous Huxley to mescaline, by giving the novelist his first dose of the drug in 1953, which inspired him to write the classic book The Doors of Perception. The two eventually became friends, and Osmond consulted Huxley when trying to find a word to describe the effects of LSD. Huxley suggested phanerothyme, from the Greek words meaning “to show” and “spirit”, telling Osmond: “To make this mundane world sublime/ Take half a gram of phanerothyme.” But Osmond decided instead on the term psychedelic, from the Greek words psyche, meaning “mind”, and deloun, meaning “to manifest”, and countered Huxley’s rhyme with his own: “To fathom Hell or soar angelic/Just take a pinch of psychedelic.” The term he had coined was announced at the meeting of the New York Academy of Sciences in 1957.

LSD therapy peaked in the 1950s, during which time it was even used to treat Hollywood film stars, including luminaries such as Cary Grant.

LSD hit the streets in the early 1960s, by which time more than 1,000 scientific research papers had been published about the drug, describing promising results in some 40,000 patients. Shortly afterwards, however, the investigations of LSD as a therapeutic agent came to an end.

{ ScienceBlogs/Neurophilosophy | Continue reading }

photo { Lina Scheynius }

Linguistics, drugs, flashback, ideas, science | November 1st, 2010 7:55 pm

flashback, photogs | November 1st, 2010 6:32 pm

The kymograph was invented by Carl Ludwig in 1847.

P. van Bronswijk argues that the kymograph was the first recording device used to record and compare the influence of drug effects. Specifically, the kymograph enabled the study of the influence of drugs on a specific organ, which van Bronswijk says enabled the development of Pharmacology as an independent science in its own right.

{ History of Psychology | Continue reading }

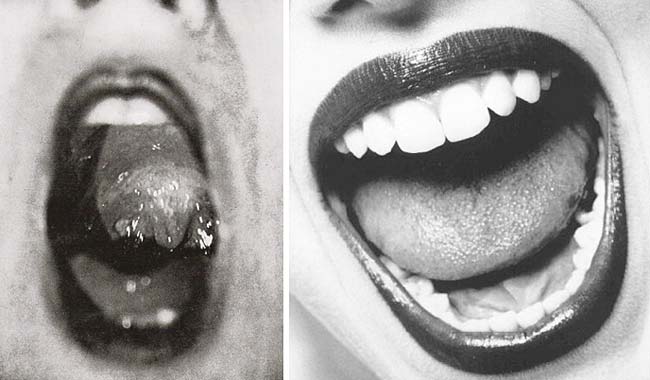

photos { 1. Jacques André Boiffard, 1929 | 2. Paige de Ponte }

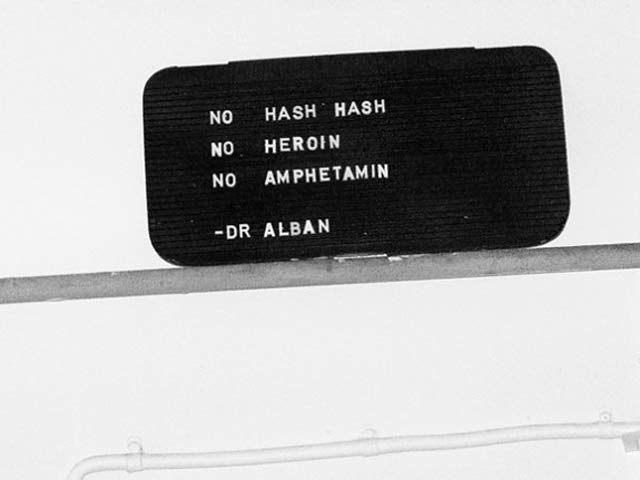

drugs, flashback, halves-pairs | November 1st, 2010 4:32 pm