ideas

Dignity is apparently big in parts of ethics, particularly as a reason to stop others doing anything ‘unnatural’ regarding their bodies, such as selling their organs, modifying themselves or reproducing in unusual ways. Dignity apparently belongs to you except that you aren’t allowed to sell it or renounce it. Nobody who finds it important seems keen to give it a precise meaning. So I wondered if there was some definition floating around that would sensibly warrant the claims that dignity is important and is imperiled by futuristic behaviours.

{ Meteuphoric | Continue reading }

photo { Manolo Campion }

experience, ideas | February 25th, 2010 8:51 pm

In the emergent “panspectric” order, human society is seen in terms of “information traffic.” (…)

The purpose of the article is to reassure readers: cold and inhuman “traffic flows” that circulate through various channels, “regardless of who or what”, is quite different from “an individual”, “a specific actual person” – the human subject. However, Tolgfors’ reasoning avoids a crucial point: more and more actors – the security services and large companies, but also academics and activists – have started to see human society as nothing more than “flows” of influences. The more information channel flows are logged in detail, the better insight we gain into people’s psyches. (…)

According to Deleuze, in emergent societies of control, we are dispersed individuals: “We no longer find ourselves dealing with the ‘mass-individual’ dyad. Individuals have become dividuals and masses, samples, data, markets, or banks.” The computer is more interested in finding patterns in the huge amount of data currently generated by the human multitude: increasingly extensive areas of our everyday analogue experience are being transferred and stored as digital data.

{ Karl Palmas/Eurozine | Continue reading }

ideas | February 25th, 2010 8:47 pm

Over the last 30 years, the US financial system has grown to proportions threatening the global economic order. This column suggests a ‘doomsday cycle’ has infiltrated the economic system and could lead to disaster after the next financial crisis. It says the best route to creating a safer system is to have very large and robust capital requirements, which are legislated and difficult to circumvent or revise. (…)

The doomsday cycle has several simple stages. At the start, creditors and depositors provide banks with cheap funding in the expectation that if things go very wrong, our central banks and fiscal authorities will bail them out. Banks such as Lehman Brothers – and many others in this past cycle – use the funds to take large risks, with the aim of providing dividends and bonuses to shareholders and management.

Through direct subsidies (such as deposit insurance) and indirect support (such as central bank bailouts), we encourage our banking system to ignore large, socially harmful ‘tail risks’ – those risks where there is a small chance of calamitous collapse. As far as banks are concerned, they can walk away and let the state clean it up. Some bankers and policymakers even do well during the collapse that they helped to create.

{ Peter Boone and Simon Johnson/VOX | Continue reading }

economics, ideas | February 25th, 2010 8:44 pm

An old Greek fable famously tells the story of a fox, who tries really hard to get his hands on a tasty vine of grapes. The fox tries and he tries, but eventually fails in all of his attempts to acquire the grapes; at which point the fox calmly continues with his life by convincing himself that he really didn’t want those grapes that badly after all…

Although there is a common wisdom in this tale of how we deal with being thwarted in our desires, a more modern psychological account of the fox’s tale may look a little different: i.e. if the fox in our tale had been reading today’s psychological journals he may have concluded, more precisely, that had he continued in his efforts, and finally obtained the grapes, THEN he may not have liked them as much.

To see why the fox may have concluded this, we must first consider that from a physiological (and pharmacological) perspective, wanting something and liking something do not necessarily go hand-in-hand, and that they certainly aren’t the same thing. For example, a drug addict really, really wants her fix, but many addicts genuinely report not particularly liking their subsequent drugged out experiences. Additionally, a number of psychological studies show that liking and wanting can be independently manipulated, and that often times both operate at a subconscious level.

{ Daniel R Hawes | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | February 25th, 2010 8:35 pm

As an illustration of the approach to media we are proposing, consider the case of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s election in 2003 to the governorship of California. Schwarzenegger’s victory has often been attributed to his status as a Hollywood star, as if that somehow guaranteed success.

But this explanation, in our view, falls far short. If it were adequate, we would have to explain the fact that the vast majority of governors and other political officeholders in this country are not actors or other media celebrities, but practitioners of that arcane and tedious profession known as the law. If Hollywood stardom were a sufficient condition to attain political office, Congress would be populated by Susan Sarandons and Sylvester Stallones, not Michele Bachmanns and Ed Markeys.

Something other than media stardom was clearly required. And that something was the nature of the legal and political systems that give California such a volatile and populist political culture, namely the rules that allow for popular referendums and, more specifically, make it relatively easy to recall an unpopular governor. California has, in other words, a distinctive set of political mediations in place that promote immediacy in the form of direct democracy and rapid interventions by the electorate. It is difficult to imagine the Schwarzenegger episode occurring in any other state.

{ Critical Terms for Media Studies, edited by W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark B. N. Hansen | The University of Chicago Press | Continue reading }

U.S., ideas, l.a. pros and cons, showbiz | February 25th, 2010 8:32 pm

Lyotard focused on the idea of narratives. Past periods, Modernism in particular, had been fond of what he called “meta-narratives,” all-inclusive narrative frameworks that explained everything, more or less.

{ The Smart Set | Continue reading }

ideas | February 24th, 2010 8:47 am

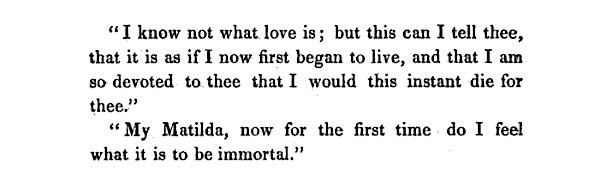

books, ideas, relationships | February 18th, 2010 5:22 pm

What’s your permanent age?

I’ve observed that everyone has a permanent age that appears to be set at birth. For example, I’ve always been 42-years old. I was ill-suited for being a little kid, and didn’t enjoy most kid activities. By first grade I knew I wanted to be an adult, with an established career, car, house and a decent tennis game. I didn’t care for my awkward and unsettled twenties. And I’m not looking forward to the rocking chair. If I could be one age forever, it would be 42.

When I ask people about their permanent age, they usually beg it off by saying they don’t have one. But if you press, you always get an answer. And the age they pick won’t surprise you. Some people are kids all their lives. They will admit they are 12-years old. Other people have always had senior citizen interests and perspectives. If you’re 30-years old in nominal terms, but you love bingo and you think kids should stop wearing those big baggy pants and listening to hip-hop music, your permanent age might be 60.

Another way to divide people is by asking if they live in the present or the future. I live in the future. I don’t dwell on the past. I’m always thinking about what’s next. (….) Some people are locked in the past; it sneaks into all of their conversations and colors their perceptions more than it should. They spend their lives either consciously or unconsciously trying to turn the future into the past. They tend to be unhappy.

{ Scott Adams | Continue reading }

photo { Steve Buscemi by Abbey Drucker }

archives, experience, ideas, time | February 18th, 2010 5:20 pm

The aim of the present paper was to evaluate the current state of knowledge on the perception of facial attractiveness and to assess the opportunity for research on poorly explored issues regarding facial preferences. (…) In spite of thousands of studies conducted, facial attractiveness research may be regarded as rather poorly progressed, although prospects for it are good. (…)

1. The meaning of attractiveness. A researcher may tell a judge how to interpret the notion of “attractiveness,” or the judge may him- or herself explicitly or implicitly define the meaning of the attractiveness. Qualities of attractiveness are able to be distinguished in terms of a spouse, a lover, a friend, or a co-worker, etc. People may judge FacA in individuals of their own sex in order to estimate their competitiveness on the mate market, or they may make a judgement about their own facial attractiveness (FacA) to estimate their own competitiveness, or they may assess FacA of their children so as to decide about how much should be invested in them, etc.

2. The characteristics of the judge. Many factors influence an individual’s pattern of facial preferences (FacP): genes, cultural norms and fads, lifetime experience, biological, ecological, physiological and psychological state of the judge, his knowledge or idea about the owner of the face examined, and the perceived similarity of the examined face to his own face [Kościński 2008].

3. The face’s category. The perception of the judge as to affiliation of the face to a category (e.g., sexual, age, racial) may influence their assessment of the face and, thereby, the judgement of FacA. For example, a face of androgynous appearance may be taken for male or female one, which can influence its perception [Webster et al. 2004].

Thus, the assessment of FacA is the method by which a person maps a facial image onto various evaluative judgements about the “imagined” owner of a face. The scope of research on FacA should comprise all biologically and socially significant forms of facial assessments (i.e., various senses of attractiveness and various facial categories) made by judges having diverse traits.

{ Krzysztof Koscinski, Current status and future directions of research on facial attractiveness, Anthropological Review, Vol. 72, 45–65 (2009) | PDF | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology, relationships | February 18th, 2010 5:18 pm

The way in which the other presents himself, exceeding the idea of the other in me, we here name face. (…)

The face brings a notion of truth which is not the disclosure of an impersonal Neuter, but expression: the existent breaks through all the envelopings and generalities of Being to spread out in its “form” the totality of its “content,” finally abolishing the distinction between form and content. (…)

…to receive from the Other beyond the capicity of the I, which means exactly: to have the idea of infinity.

{ Emmanuel Levinas, Totality and Infinity, 1961 }

ideas | February 18th, 2010 5:17 pm

What is nostalgia good for? A Standard Life study suggests 28 to 40-year-olds don’t plan for the future because they prefer to reminisce about past times. (…)

In recent years, psychologists have been trying to analyse the powerful and enduring appeal of our own past - what Mr Routledge calls the “psychological underpinnings of nostalgia”.

“Why does it matter? Why would a 40-year-old man care about a car he drove when he was 18?” he asks. It matters, quite simply, because nostalgia makes us feel good.

Once nostalgia was considered a sickness - the word derives from the Greek “nostos” (return) and “algos” (pain), suggesting suffering due to a desire to return to a place of origin. (…)

“Nostalgia is a way for us to tap into the past experiences that we have that are quite meaningful - to remind us that our lives are worthwhile, that we are people of value, that we have good relationships, that we are happy and that life has some sense of purpose or meaning.” (…)

Nostalgia is usually involuntary and triggered by negative feelings - most commonly loneliness - against which it acts as a sort of natural anti-depressant by countering those feelings.

{ BBC | Continue reading }

Linguistics, flashback, psychology, time | February 18th, 2010 5:12 pm

Has everybody forgotten that the arts are recession proof? Yes, of course, revenues shrink, contributions dry up, and expenses continue to rise. (…)

But the arts—the play of the imagination, the need for this parallel universe with its dream logic and its moral reverberations—are not affected by shifts in the housing market or the Dow.

The value of a painting has never been established at auction. The power of a novel has never been determined by the advance the author happened to receive or by the number of copies that eventually sold. The greatness of a theatrical production has nothing to do with how many people attend. Dancers who can barely make their rent go on stage and give opulent performances. Poets, with nothing but a pencil and a piece of paper, erect imperishable kingdoms. And there are millionaires who chose to live with the barebones beauty of a Mondrian or a Morandi.

{ The New Republic | Continue reading }

art, economics, ideas | February 18th, 2010 5:08 pm

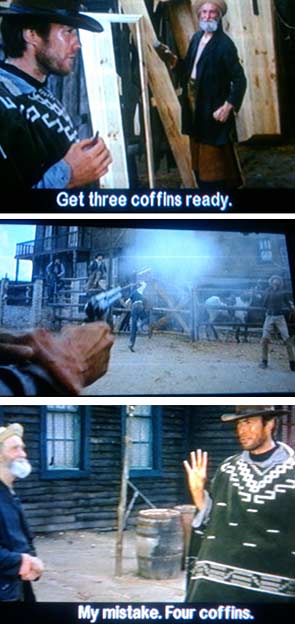

The principle of Occam’s razor suggests that the simplest hypothesis is usually the correct one — or as the character Gil Grissom in “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation” succinctly puts it, if you hear hoofbeats, “think horses, not zebras.”

In his lively new book, “Voodoo Histories,” the journalist David Aaronovitch uses Occam’s razor to eviscerate the many conspiracy theories that have percolated through politics and popular culture over the last century, from those that assert that the 9/11 terrorist attacks were actually a United States government plot to those that claim that Diana, Princess of Wales, was murdered at the direction of the royal family or British intelligence.

In most cases, Mr. Aaronovitch notes, conspiracy theorists would rather tie themselves into complicated knots and postulate all sorts of improbable secret connections than accept a simple, more obvious explanation. (…)

Does the Internet, with its increased democratization of information, help spread conspiracy theories or help expose them? Mr. Aaronovitch says that it was obvious that “sites endorsing 9/11 conspiracy theories and those subscribing to them in passing far outnumbered sites devoted to debunking or refuting such theories.”

He writes that the Internet has enabled the “release of a mass of undifferentiated information, some of it authoritative, some speculative, some absurd,” and that “cyberspace communities of semi-anonymous and occasionally self-invented individuals have grown up, some of them permitting contact between people who in previous times might have thought each other’s interests impossibly exotic and even mad.”

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

books, ideas, scams and heists | February 18th, 2010 5:07 pm

Zachary Mason’s critically praised first novel comes with a largely self-explanatory title: “The Lost Books of the Odyssey” purports to be a compilation of 44 alternate versions of Homer’s epic. What that title cannot possibly convey, though, is the unusual journey of Mr. Mason’s manuscript on its way to publication by Farrar, Straus & Giroux last week.

Mr. Mason, 35, a computer scientist specializing in search recommendation systems and keywords, once worked at Amazon.com. He avoided writing workshops and M.F.A. programs as a matter of principle, and produced “The Lost Books” at night, during lunch breaks and on weekends and vacations. (…)

In person, Mr. Mason is extremely soft-spoken and tends to talk in a flat, unemotional tone, though he does note with regret that he “turned down Google two weeks before their I.P.O.” (He’s now employed at a Silicon Valley start-up.) He approaches literature almost as if it were a branch of science, governed by laws that are quantifiable and predictable, as when he talks of devising an algorithm, later discarded, to determine an optimum chapter order for his novel or when he compares writing to the annealing of metals.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

books, technology | February 11th, 2010 8:33 am

The long-term effects of short-term emotions

The heat of the moment is a powerful, dangerous thing. We all know this. If we’re happy, we may be overly generous. Maybe we leave a big tip, or buy a boat. If we’re irritated, we may snap. Maybe we rifle off that nasty e-mail to the boss, or punch someone. And for that fleeting second, we feel great. But the regret—and the consequences of that decision—may last years, a whole career, or even a lifetime.

At least the regret will serve us well, right? Lesson learned—maybe.

Maybe not. My friend Eduardo Andrade and I wondered if emotions could influence how people make decisions even after the heat or anxiety or exhilaration wears off. We suspected they could. As research going back to Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory suggests, the problem with emotional decisions is that our actions loom larger than the conditions under which the decisions were made. When we confront a situation, our mind looks for a precedent among past actions without regard to whether a decision was made in emotional or unemotional circumstances. Which means we end up repeating our mistakes, even after we’ve cooled off.

{ Harvard Business Review | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | February 4th, 2010 9:24 am

My impossible ones. — Seneca: or the toreador of virtue. (…) Dante: or the hyena who writes poetry in tombs. (…) Victor Hugo: or the pharos at the sea of nonsense. (…) Michelet: or the enthusiasm which takes off its coat. Carlyle: or pessimism as a poorly digested dinner. (…) Zola: or “the delight in stinking.”

{ Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, 1888 | Continue reading }

haha, nietzsche | February 4th, 2010 9:24 am

Who are the best spreaders of information in a social network? The answer may surprise you.

The study of social networks has thrown up more than a few surprises over the years. It’s easy to imagine that because the links that form between various individuals in a society are not governed by any overarching rules, they must have a random structure. So the discovery in the 1980s that social networks are very different came as something of a surprise. In a social network, most nodes are not linked to each other but can easily be reached by a small number of steps. This is the so-called small worlds network.

Today, there’s another surprise in store for network connoisseurs courtesy of Maksim Kitsak at Boston University and various buddies. One of the important observations from these networks is that certain individuals are much better connected than others. These so-called hubs ought to play a correspondingly greater role in the way information and viruses spread through society.

In fact, no small effort has gone into identifying these individuals and exploiting them to either spread information more effectively or prevent them from spreading disease.

The importance of hubs may have been overstated, say Kitsak and pals. “In contrast to common belief, the most influential spreaders in a social network do not correspond to the best connected people or to the most central people,” they say.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

illustration { Martin Wong’s Ferocactus }

ideas, science, technology | February 4th, 2010 9:24 am

When most people think about geography, they think about maps. Lots of maps. Maps with state capitals and national territories, maps showing mountains and rivers, forests and lakes, or maps showing population distributions and migration patterns. And indeed, that isn’t a wholly inaccurate idea of what the field is all about. It is true that modern geography and mapmaking were once inseparable. (…)

In our own time, another cartographic renaissance is taking place. In popular culture, free software applications like Google Earth and MapQuest have become almost indispensable parts of our everyday lives: we use online mapping applications to get directions to unfamiliar addresses and to virtually “explore” the globe with the aid of publicly available satellite imagery. Consumer-available GPS have made latitude and longitude coordinates a part of the cultural vernacular. (…)

Geography, then, is not just a method of inquiry, but necessarily entails the production of a space of inquiry. Geographers might study the production of space, but through that study, they’re also producing space. Put simply, geographers don’t just study geography, they create geographies. (…)

Experimental geography means practices that take on the production of space in a self-reflexive way, practices that recognize that cultural production and the production of space cannot be separated from each another, and that cultural and intellectual production is a spatial practice.

{ The Brooklyn Rail | Continue reading }

illustration { Olivier Vernon }

ideas, science | February 4th, 2010 9:15 am

What a surprise that big name philosophers, who in previous years did not hesitate to share their profound wisdom in a language that was philosophical but plain, nuanced but direct, now seemed to be hiding behind words. It was as if there was something they could not say. Their presentations became more academic, their focus more narrowed. The absence of a theme was obvious and that, I believe, was the only theme.

We are in a moment of cultural stagnation where the only thing to say is that we have nothing to say. The great contemporary philosophers of our age are in intellectual retreat. Something about this historical moment is leaving the discipline of Western philosophy blind. The great minds seem aware of a presence, but unable to get to it directly. So they fill the air with empty words that, while philosophically interesting, simply serve as a placeholder, a time-filler while events unfold.

{ Micah M. White/Adbusters | Continue reading }

ideas | February 4th, 2010 9:10 am

In 1966, William Labov, the father of sociolinguistics, discovered that many people with New York accents — the stock Noo Yawk kind — didn’t like the way they talked. It was kind of sad. Labov found widespread “linguistic self-hatred,” he reported. People from New York and New Jersey described their own speech as “distorted,” “sloppy” and “horrible.” No wonder those great old accents came to be regarded as a class giveaway, to be thrown over in the name of assimilation, refinement and the acquisition of Newscaster English.

But that was the ’60s, back before the never-ending you-tawkin-t’me aria was enshrined in movies like “Mean Streets,” “Saturday Night Fever,” “Working Girl” and, of course, “Taxi Driver.” Before long, people were consciously cultivating the once-despised dialect. Now an extra-hammy version of the accent — which thrives in the New York City area, including northern New Jersey — is a point of fighting pride, most recently among the brawling bozos on MTV’s captivating and incendiary reality show “Jersey Shore.”

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

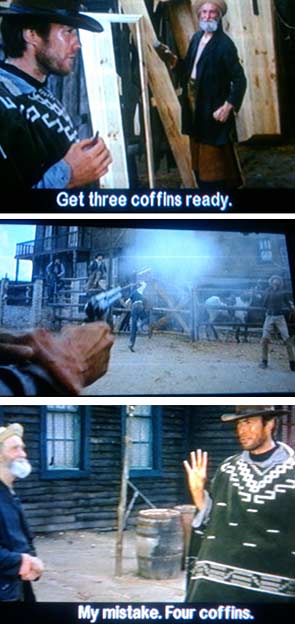

Johnny Boy: Y’know Joey Clams…

Charlie: Yeah.

Johnny Boy: …Joey Scallops, yeah.

Charlie: I know him too, yeah.

Johnny Boy: …yeah. No. No, Joey Scallops is Joey Clams.

Charlie: Right.

Johnny Boy: Right.

Charlie: …they’re the same person!

Johnny Boy: Yeah!

Charlie: ‘ey!

Johnny Boy: ‘ey…

{ Mean Streets, 1973 }

artwork { Mo Maurice Tan }

Linguistics, new york | February 4th, 2010 9:10 am