ideas

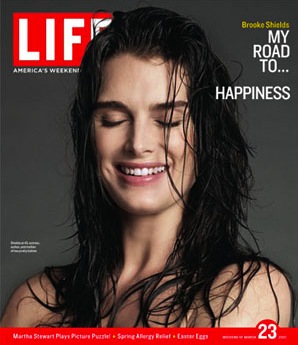

It was followed in late 1936 by Life, the picture magazine, which was an astonishing newsstand success: “By the end of 1937 . . . circulation had reached 1.5 million — more than triple the first-year circulation of any magazine in American (and likely world) history.” But then, as throughout much of its existence, Life was troubled by high production costs and insufficient advertising revenues.

Luce’s empire grew to include “The March of Time,” first a radio broadcast and then a newsreel for theatrical distribution, and finally, in 1954, the slow-growing but eventually phenomenally successful Sports Illustrated.

The empire was called Time, Incorporated, a name that no longer exists. In 1990 — 23 years after Luce’s death — it merged with Warner Brothers and has since been known as Time Warner, a partnership that has seen its rough times but is now “one of the three largest media companies in the United States.” It is “a powerful and successful company, although the magazine division that had launched the company [is] weakening fast in the digital world of the twenty-first century.” Time, which was required reading in the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s, even for those who detested it, seems now to be waiting-room reading; Fortune retains relatively strong circulation but seems primarily known for its “Fortune 500″ rankings; and Sports Illustrated, though still widely read, is no longer noteworthy, as it once was, for superb journalism that at times reached the lower rungs of literature.

{ Washington Post | Continue reading }

books, economics, press | April 21st, 2010 10:00 am

An ‘immortal’ jellyfish is swarming through the world’s oceans, according to scientists.

Since it is capable of cycling from a mature adult stage to an immature polyp stage and back again, there may be no natural limit to its life span. Scientists say the hydrozoan jellyfish is the only known animal that can repeatedly turn back the hands of time and revert to its polyp state (its first stage of life).

{ Yahoo Green | Continue reading | Telegraph }

photo { Jackson Eaton }

jellyfish, science, time | April 16th, 2010 7:49 am

With social networking sites enabling the romantically inclined to find out more about a potential lover before the first superficial chat than they previously would have in the first month of dating, this is an important question for the future of romance.

{ Meteuphoric | Continue reading }

photo { Stephen Shore, Amarillo, Texas, August, 1973 }

ideas, relationships, social networks, technology | April 16th, 2010 7:01 am

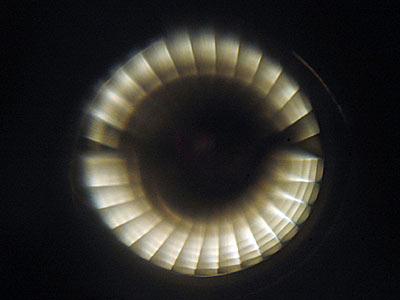

{ A beam of light is depicted travelling between the Earth and the Moon in the same time it takes light to scale the distance between them: 1.255 seconds at its mean orbital (surface to surface) distance. The relative sizes and separation of the Earth–Moon system are shown to scale. | Wikipedia | Related: Where is the best clock in the universe? The widespread belief that pulsars are the best clocks in the universe is wrong, say physicists. }

science, time | April 15th, 2010 7:57 am

Is the happy life characterized by shallow, happy-go-lucky moments and trivial small talk, or by reflection and profound social encounters? Both notions—the happy ignoramus and the fulfilled deep thinker—exist, but little is known about which interaction style is actually associated with greater happiness (King & Napa, 1998). In this article, we report findings from a naturalistic observation study that investigated whether happy and unhappy people differ in the amount of small talk and substantive conversations they have. (…)

Naturally, our correlational findings are causally ambiguous. On the one hand, well-being may be causally antecedent to having substantive interactions; happy people may be “social attractors” who facilitate deep social encounters (Lucas & Dyrenforth, 2006). On the other hand, deep conversations may actually make people happier. (…)

Remarking on Socrates’ dictum that “the unexamined life is not worth living,” Dennett (1984) wrote, “The overly examined life is nothing to write home about either” (p. 87). Although we hesitate to enter such delicate philosophical disputes, our findings suggest that people find their lives more worth living when examined―at least when examined together.

{ Psychological Science | Continue reading }

collage { never always }

ideas, psychology, relationships | April 15th, 2010 7:45 am

Deciding what is and isn’t a planet is a problem on which the International Astronomical Union has generated a large amount of hot air. The challenge is to find a way of defining a planet that does not depend on arbitrary rules. For example, saying that bodies bigger than a certain arbitrary size are planets but smaller ones are not will not do. The problem is that non-arbitrary rules are hard to come by.

In 2006, the IAU famously modified its definition of a planet in a way that demoted Pluto to a second class member of the Solar System. Pluto is no longer a full blown planet but a dwarf planet along with a handful of other objects orbiting the Sun.

The IAU’s new definition of a planet isan object that satisfies the following three criteria. It must be in orbit around the Sun, have sufficient mass to have formed into a nearly round shape and it must have cleared its orbit of other objects.

Pluto satisfies the first two criteria but fails on the third because it crosses Neptune’s orbit(although, strangely, Neptune passes).

Such objects are officially called dwarf planets and their definition is decidedly arbitrary. In its infinite wisdom, the IAU states that dwarf planets are any transNeptunian objects with an absolute magnitude less than +1 (ie a radius of at least 420 km).

Today, Charles Lineweaver and Marc Norman at the Australian National University in Canberra focus on a new way of defining dwarf planets which is set to dramatically change the way we think about these obects.

The problem boils down to separating the potato-shaped objects in the Solar System from the spherical ones.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

photo { Max Langhurst }

science, space, theory | April 14th, 2010 2:10 pm

…and it may be that the immobility, the inertia, the absence of all active passion or incident or peril which such a retired existence imposed upon man led him to create, in the midst of the world of nature, another and an impossible world, in which he found comfort and relief for his idle intellect, explanations of the more ordinary sequences of events, and extraneous solutions of extraordinary phenomena. (…)

…for him the legend confounded itself with life, and, unconsciously, he found himself regretting that the legend differed from life, and that life differed from the legend.

{ Ivan Goncharov, Oblomov, 1859 | Continue reading }

{ uncredited photo | any thought? }

books, ideas, photogs | March 23rd, 2010 2:40 pm

Religious architecture and art were to medieval feudalism what advertising and commercialism are to modern capitalism: A rather effective way to build support for the status quo using aesthetics instead of argument. My claim, in short, is that Notre Dame played the same role during the Middle Ages that fashion magazines play today. Notre Dame was not an argument for feudalism, and Elle is not an argument for capitalism. But both are powerful ways to make regular people buy into the system.

{ EconLog | Continue reading }

art, ideas | March 23rd, 2010 2:20 pm

In any case, suffering is not something to be sought, but, since it is unavoidable, when one does encounter it, one must learn to use it for good. The person who has gone through suffering, and emerges better from the experience, is strengthened but it was not the suffering but the person’s own moral fibre that made them better.

{ Peter Bolton | Continue reading }

Take psychic suffering first of all. Severe depression is one of the most acute forms of pain known to humanity. Those who have suffered from both depression and serious physical illness are almost unanimous in agreeing that the depression is worse. Does this make them better people? Certainly not at the time. I’ve seen depression close up with several people, and one of them hit the nail on the head when they said that depression makes you really selfish. You can see that it’s taking its toll on people close to you, but you are just too self-absorbed to change how you treat them.

Are they better having come through the depression? I see no evidence for this, I’m afraid.

{ Julian Baggini | Continue reading | More: Does suffering improve us? | The Guardian }

photo { Shane Lavalette }

health, ideas | March 23rd, 2010 2:16 pm

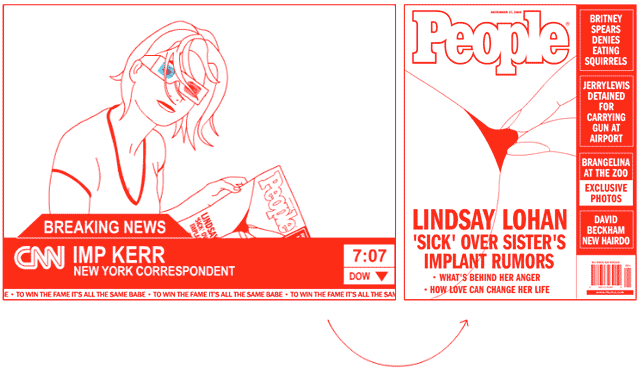

it always makes me perplexed when people refuse eternal youth. […] ulysses: ‘i’m glad someone invented death.’

archives, celebs, imp, time | March 23rd, 2010 2:07 pm

Most people in most places simply won’t be able to find a toilet when they need one. And for women, the lack of decent facilities is more than a problem. It’s an emergency. Public conveniences are the final battleground in the sex wars, the ultimate declaration of discrimination. (…)

You may think of America as the country that created the allergy, where bathroom culture rules, where germs and dirt are feared more than global warming and where cleanliness is worshipped alongside godliness – but public conveniences in some of its major cities are a disgrace. New York City, for example, is one of the most sophisticated metropolises in the world. Yet its provision of any public toilets at all, let alone clean and decent ones, is woeful. (…)

Today, there are still far fewer public toilets for women than for men in many British cities, in terms of both the number of toilets available and the ratio of male to female facilities. But even if the numbers were more equal, that wouldn’t solve the problem, according to the American sociologist Harvey Molotch, because women suffer “special burdens of physical discomfort, social disadvantage, psychological anxiety” when in public.

{ New Humanist | Continue reading }

photo { Stephen Shore, New York City, New York,September-October 1972 }

economics, health, ideas | March 23rd, 2010 2:05 pm

Music does not express this or that particular and definite joy, this or that sorrow, or pain, or horror, or delight, or merriment, or peace of mind; but joy, sorrow, pain, horror, delight, merriment, peace of mind themselves, to a certain extent in the abstract, their essential nature, without accessories, and therefore without their motives. Yet we completely understand them in this extracted quintessence. (…)

Music, if regarded as an expression of the world, is in the highest degree a universal language, which is related indeed to the universality of concepts, much as they are related to the particular things. (…)

This deep relation which music has to the true nature of all things also explains the fact that suitable music played to any scene, action, event, or surrounding seems to disclose to us its most secret meaning, and appears as the most accurate and distinct commentary upon it. This is so truly the case, that whoever gives himself up entirely to the impressions of a symphony, seems to see all the possible events of the world take place in himself, yet if he neglects, he can find no likeness between the music and the things that passed before his mind.”

{ Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation, 1818 }

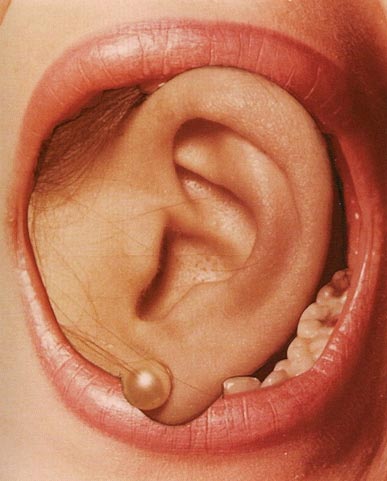

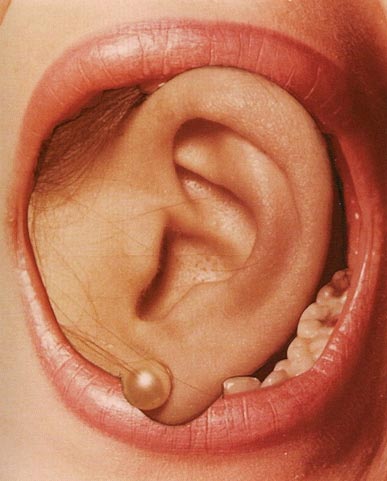

photo { Noritoshi Hirakawa }

ideas, music | March 23rd, 2010 2:03 pm

books, economics, video | March 23rd, 2010 12:59 pm

Would you be happier if you spent more time discussing the state of the world and the meaning of life — and less time talking about the weather?

It may sound counterintuitive, but people who spend more of their day having deep discussions and less time engaging in small talk seem to be happier, said Matthias Mehl, a psychologist at the University of Arizona who published a study on the subject.

“We found this so interesting, because it could have gone the other way — it could have been, ‘Don’t worry, be happy’ — as long as you surf on the shallow level of life you’re happy, and if you go into the existential depths you’ll be unhappy,” Dr. Mehl said.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

photo { Laura Taylor }

ideas, leisure, psychology | March 20th, 2010 9:00 am

Finally I went to 104, still musing, alarmed by the grim power of this corner of Paris, passing in front of the hotel Royal-Aboukir (what a name!). All this was like some disinherited New York neighborhood, on the smaller Parisian scale. At dinner (a good risotto, but the beef, of course, not cooked at all), I felt comfortable with friends: A. C., Philippe Roger, Patricia, and a young woman, Frédérique, who was wearing a rather formal gown, its unusual shade of blue soothing; she didn’t say much, but she was there , and I thought that such attentive and marginal presences were necessary to the good economy of a party. (…)

In the taxi on the way home, storm and heavy rain. I hang around the house (eating some toast and feta), then, telling myself I must lose the habit of calculating my pleasures (or my deflections), I leave the house again and go see the new porno film at Le Dragon: as always—and perhaps even more so than usual—dreadful. I dare not cruise my neighbor, though I probably could (idiotic fear of being rejected). Downstairs into the back room; I always regret this sordid episode afterward, each time suffering the same sense of abandonment.

{ Roland Barthes, Incidents, 1979 | Continue reading }

experience, roland barthes | March 18th, 2010 4:50 pm

We live in a world of complex systems. The environment is a complex system. The government is a complex system. Financial markets are complex systems. The human mind is a complex system—most minds, at least.

By a complex system I mean one in which the elements of the system interact among themselves, such that any modification we make to the system will produce results that we cannot predict in advance.

Furthermore, a complex system demonstrates sensitivity to initial conditions. You can get one result on one day, but the identical interaction the next day may yield a different result. We cannot know with certainty how the system will respond.

Third, when we interact with a complex system, we may provoke downstream consequences that emerge weeks or even years later. We must always be watchful for delayed and untoward consequences.

The science that underlies our understanding of complex systems is now thirty years old. A third of a century should be plenty of time for this knowledge and to filter down to everyday consciousness, but except for slogans — like the butterfly flapping its wings and causing a hurricane halfway around the world — not much has penetrated ordinary human thinking.

On the other hand, complexity theory has raced through the financial world. It has been briskly incorporated into medicine. But organizations that care about the environment do not seem to notice that their ministrations are deleterious in many cases. Lawmakers do not seem to notice when their laws have unexpected consequences, or make things worse. Governors and mayors and managers may manage their complex systems well or badly, but if they manage well, it is usually because they have an instinctive understanding of how to deal with complex systems. Most managers fail.

Why? Our human predisposition treat all systems as linear when they are not. A linear system is a rocket flying to Mars. Or a cannonball fired from a cannon. Its behavior is quite easily described mathematically. A complex system is water gurgling over rocks, or air flowing over a bird’s wing. Here the mathematics are complicated, and in fact no understanding of these systems was possible until the widespread availability of computers.

One complex system that most people have dealt with is a child. If so, you’ve probably experienced that when you give the child an instruction, you can never be certain what response you will get. Especially if the child is a teenager. And similarly, you can’t be certain that an identical interaction on another day won’t lead to spectacularly different results.

If you have a teenager, or if you invest in the stock market, you know very well that a complex system cannot be controlled, it can only be managed. Because responses cannot be predicted, the system can only be observed and responded to. The system may resist attempts to change its state. It may show resiliency. Or fragility. Or both.

An important feature of complex systems is that we don’t know how they work. We don’t understand them except in a general way; we simply interact with them. Whenever we think we understand them, we learn we don’t. Sometimes spectacularly.

{ Michael Crichton | Continue reading }

archives, economics, ideas, science | March 18th, 2010 2:55 pm

Is mental illness good for you?

Mental illness is surprisingly common. About 10% of the population is affected by it at any one time and up to 25% suffer some kind of mental illness over their lifetime. This has led some people (many people in fact) to surmise that it must exist for a reason – in particular that it must be associated with some kind of evolutionary advantage. Indeed, this is a popular and persistent idea both in scientific circles and in the general public.

Such theories come in two main varieties – the first, that mental illness confers some specific advantage to those afflicted; and second, that the mutations which cause mental illness in one person’s genetic background may confer an advantage when they are in a different genetic background (balancing selection).

{ Wiring the brain | Continue reading }

health, ideas, psychology, science | March 18th, 2010 2:40 pm

When people think of knowledge, they generally think of two sorts of facts: facts that don’t change, like the height of Mount Everest or the capital of the United States, and facts that fluctuate constantly, like the temperature or the stock market close.

But in between there is a third kind: facts that change slowly. These are facts which we tend to view as fixed, but which shift over the course of a lifetime. For example: What is Earth’s population? I remember learning 6 billion, and some of you might even have learned 5 billion. Well, it turns out it’s about 6.8 billion. (…)

These slow-changing facts are what I term “mesofacts.” Mesofacts are the facts that change neither too quickly nor too slowly, that lie in this difficult-to-comprehend middle, or meso-, scale. (…)

Updating your mesofacts can change how you think about the world. Do you know the percentage of people in the world who use mobile phones? In 1997, the answer was 4 percent. By 2007, it was nearly 50 percent.

{ The Boston Globe | Continue reading }

photo { Daemian and Christine }

psychology, time | March 18th, 2010 2:30 pm

There is increasing awareness within the Defense Department that wars are interactively complex or “wicked” problems. (…) This article will examine the challenges interactively complex problems pose to U.S. military planning and doctrine. It will offer some modest suggestions for dealing with these problems. We use the terms “interactively complex,” “ill-structured” and “wicked” interchangeably throughout the article. (…)

Ill-structured problems are interactively complex. By definition, these problems are nonlinear. Small changes in input can create massive changes in outcome, and the same action performed at different times may create entirely different results. It is very difficult if not impossible to predict what will happen. Yet our war-planning process often promulgates detailed plans for well over the first 100 days of a conflict. Obviously, the true value of planning comes from the interactions of those doing the planning, not the plan itself. By shifting our planning focus from details of the plan to defining the problem, we can reap the benefits of intensive planning while exploring other problem definitions that should drive branch planning.

Ill-structured problems have no “stopping rule.” By definition, wicked problems have no end state. Rather, the planner must seek a “good enough” solution based on maintaining equilibrium around some acceptable condition. Unfortunately, our doctrine and practice continue to focus on developing an end state for every plan. When dealing with wicked problems, thinking in terms of an end state will almost certainly lead to failure. Instead, we should think about how to sustain “steady state” over the long term. While apparently a semantic quibble, accepting that wicked problems don’t “end” is vitally important for campaign planners and commanders alike.

{ Armed Force Journal | Continue reading }

U.S., ideas, incidents | March 18th, 2010 2:24 pm

An American essayist, poet, and popular philosopher, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–82) began his career as a Unitarian minister in Boston, but achieved worldwide fame as a lecturer and the author of such essays as “Self-Reliance,” “History,” “The Over-Soul,” and “Fate.”

He influenced generations of Americans, from his friend Henry David Thoreau to John Dewey, and in Europe, Friedrich Nietzsche, who takes up such Emersonian themes as power, fate, the uses of poetry and history, and the critique of Christianity. (…)

Emerson is in many ways a process philosopher, for whom the universe is fundamentally in flux and “permanence is but a word of degrees.” Even as he talks of “Being,” Emerson represents it not as a stable “wall” but as a series of “interminable oceans.” This metaphysical position has epistemological correlates: that there is no final explanation of any fact, and that each law will be incorporated in “some more general law presently to disclose itself.” (…)

Nietzsche read German translations of Emerson’s essays, copied passages from “History” and “Self-Reliance” in his journals, and wrote of the Essays: that he had never “felt so much at home in a book.” Emerson’s ideas about “strong, overflowing” heroes, friendship as a battle, education, and relinquishing control in order to gain it, can be traced in Nietzsche’s writings.

{ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy | Continue reading }

nietzsche, rw emerson | March 18th, 2010 2:23 pm